Swoon

- Text by Andrea Kurland

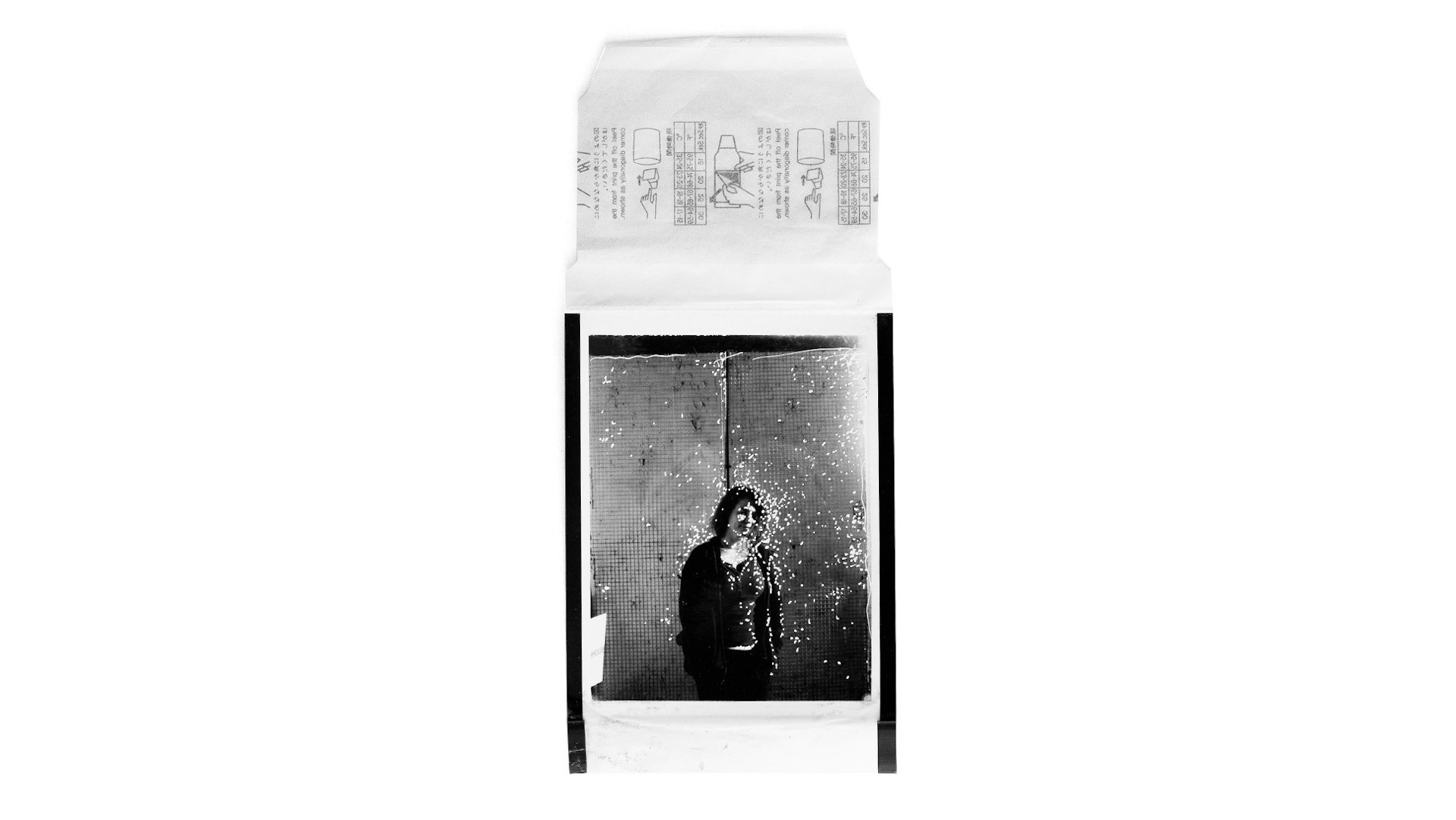

- Photography by Swoon

Caledonia Dance Currie is learning how to be a human again. She’s spent the last decade working at a preternatural pace, so for her thirty-fourth birthday, as a treat to herself, she took a break from being invincible and went for a walk. “I was so busy, I wasn’t sleeping and every time I got off an aeroplane I would get the flu,” she says. “I was like, ‘But I’m a superhero, I can do this!’ and my body was like, ‘Actually, you’re thirty-four now – stop.’”

The Brooklyn-based artist landed in London a month ago with “a giant backpack full of bits of paper” and has spent every waking hour crouched over on the floor or dangling from a ladder, so that she could chisel, hammer, paint and build a walk-in installation at Black Rat Projects. The cavernous gallery space under the railway arches of Shoreditch has long been a home to street art’s elite, and Murmuration – a show that takes its name from a flock of starlings, and features lace-like papercuts and a twenty-foot goddess called Thalassa – is the culmination of four years of hard slog. So a little downtime, you’d think, would be no big deal. “I just did a big hike in Ireland, and previously I would never have done that,” she says, scooping heavy locks off her face with ink-stained hands. “I would have been like, ‘I have to stay and finish 30,000 paintings after the show opens.’ Now I just think, ‘Please be a human being and stop doing that.’”

It’s a bright, chilly morning in post-gentrified East London, and the hip cognoscenti are still nowhere to be seen. Despite having “stayed up real late to hang out with a buddy”, Caledonia Currie – or Callie, as she’s known to her troubadour band of collaborators and friends – is clearly feeling the benefits of her Irish sojourn. Fresh-faced and chirpy, she free-pours sugar into her coffee and looks the polar opposite of annoyed when she pauses to say, “I wish Abba would die.” After a series of re-arranged plans, we’ve met for breakfast at an American-style diner that serves Huevos Rancheros and, despite the mini jukeboxes and rockabilly vibes, plays a whole lot of Abba. On a torturous loop.

“It reminds me of a café I worked in when I first moved to New York and all they fucking played was Abba,” says Callie, slicing eggs and mushrooms into a forkable mince. “People are like, ‘What have you got against Abba? They’re so cheerful!’ But I kinda wanted to go back in time and murder them.”

On paper, this statement is a little misleading. But throw in the schoolgirl giggles and excitable hand gestures (complete with waving knife and fork), and you soon get the picture: Callie was joking. People who hug like an old-school friend don’t really want to murder Abba – no matter how much you wish they would.

Caledonia Dance Currie is, amazingly, the real name of street artist Swoon, as given to her by her “non-traditional, wild-child” parents in 1977. Her childhood home in Daytona Beach, Florida, was a Petri dish of countercultural beliefs where the creative chaos of self-discovery was always met with praise. Every painting was deemed “amazing”; every drawing proof that she could dodge a prescriptive path. So, naturally, she became an artist at the age of ten.

“I was into oil painting, which had all the trappings of being serious and real,” laughs Callie, sprinkling salt onto her tomatoes for the gazillionth time. “Everyone was like, ‘You can do this!’ So, I was like, ‘That’s it, I’m an artist!’ Not too many people have that from that age. A lot of people would have been like, ‘You’re gonna lose your mind and end up on drugs,’ but my parents were like, ‘Well, we already did that so you probably won’t.’”

With the support of her teacher dad and stay-at-home mom, Callie came to understand that “having that amount of self-confidence as a young woman is a tremendous thing”. But ‘tremendous’, in this context, under-eggs the facts. Today, Swoon’s delicate aesthetic – all expressive line-work and heartfelt human forms – is a defining thread of street art’s evolving narrative and her name is dropped, next to Banksy and Shepard Fairey, everywhere its told. Her outdoor work has been brought inside by influential curators like Jeffrey Deitch, with pieces selling for $20,000 or more. She’s done a TED Talk; her work hangs in MoMA; even your mom could spot a Swoon.

But in 1996, aged nineteen, she was just another fine art student at Pratt in New York, struggling to work out where she slotted in. “I remember being in painting class and drawing this deadening blank like, ‘I have nothing to give,’” she says. “I could feel there was something ill-fitting, so I just had to look harder and dig deeper to find something that felt meaningful to me.” That search took her to Eastern Europe and the Netherlands where she spent her time on exchange immersed in the library, soaking up the work of Expressionist artists Schiele and Klimt. “When I talk to students I have to explain, ‘I grew up before the Internet, that’s kind of a big deal,’” she laughs. “All I had were books about Vincent Van Gogh.”

Back in Brooklyn, her anarchist art friends were getting into graffiti, but Callie couldn’t see herself in the tagging world. Then lightning struck. “Discovering Revs – having friends say, ‘Did you know that he wrote his entire life story on the New York subway system?’ – it blew the top off my understanding of graffiti. It felt more like this constant interaction with the city – that feeling of tricksterness, like something has been implanted in the fabric of the city.” Another revelation was Gordon Matta-Clark, whose site-specific ‘Anarchitecture’ captured the decay of the American Dream. “He’d carve abandoned houses in half, turning the city into a sculpture, then leave them to be destroyed,” says Callie. “I felt an emotional connection and knew I had to make something that embodied those principles.”

In 1999, combining her classic portraiture skills with papercut and printmaking, Callie started pasting intricate figures around New York, embedding familiar faces into the blank spaces of her world. “It was about addressing that feeling like there’s no place for you in the city,” says Callie, who prints everything at home by carving into lino-block, pressing the image into paper by walking on it with bare feet. “I needed to see my life reflected back to me.” But she wasn’t just planting something for herself. As she explains in her TED Talk: “By putting a little tiny change in an environment you can change all those associations people have, and create an opportunity for connection.”

Today, these ephemeral silhouettes, usually in varying stages of decay, have left an imprint on cities across the globe; they are the people that leave an impression on Callie’s life. “I can work on the expression of a human face for days and days and days,” she says. “I have an infinite patience for that.” A week after we share breakfast, Callie will drop by The Bank of Ideas – an abandoned UBS office block taken over by Occupy London – to give an impromptu talk to a dozen or so protesters. “I’m interested in travelling to places where people are organising themselves and just kinda figuring out the daily thing of how to survive,” she’ll say, pointing to a drawing inspired by the female sewing collectives of Oaxaca, Mexico. No one quite knows who’s inspiring who. (The following day, an email will circulate among that same group of activists that reads, ‘Post-Swoon meet up: Come with your ideas. No matter how impossible they may seem in your head.’)

In 2004, this belief in mass action manifested as the Toyshop collective, a group Callie founded with her dumpster-diving outsider-artist friends to stage colourful interventions in the name of ‘psychogeography’ – defined by Marxist theorist Guy Debord as “the effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals”. They pasted kids’ drawings over commercial billboards and paraded down Houston Street in Manhattan, wearing paper tutus and clanging instruments made of junk, like a band of post-apocalyptic anarchist faeries. “We weren’t doing anything amazingly new, as the conversation around public space was already intense,” admits Callie, who drew inspiration from the anti-M11 highway protest camps in East London – a stone’s throw from where we’re sat eating scrambled eggs – which later grew into Reclaim The Streets. “I remember learning about that and it sparked a curiosity about how people could work together to make change.”

Toyshop became a honeypot for a swarm of outliers – performance artists, carpenters, musicians and “people who make things” – eager to get their hands dirty and build their own statement. With Callie at the helm (and Jeffrey Deitch stoking the fire) they embarked on a series of progressively ambitious junkyard raft projects starting, in the summer of 2006, with Miss Rockaway Armada – a two-year-long “collective living experiment in communication and smaller footprints” that sent a flotilla of dystopian Waterworld rafts, built from construction site scraps, down the Mississippi.

“At the time we were going into all these wars and I was like, ‘Who is supporting this presidency? Who are Americans? What the fuck is going on here?’ I felt totally disconnected to the point that I wanted to leave the country,” says Callie. “I was like, ‘I either can’t be an American in this situation, or I can do what I know, mobilise an art collective, channel the entirety of our culture, and travel with it into the interior. You can’t wage a war for resources by withdrawing from the centre, and only communicating with people in your own city is stifling to the point that it loses all meaning. It was very much about, ‘How do we communicate and learn from America?’ There were these amazing moments when people spotted the boats and were like, ‘What are you?’ It sparked a conversation like, ‘This is who we are, this is what we’re doing – who are you?’”

Swimming Cities of Switchback Sea brought an aesthetic lilt to the ‘living experiment’ that was much more distinctly Swoon. When seven scrapyard vessels came floating down the Hudson River in the summer of 2008 – seemingly straight out of a Neverland New Orleans – Callie’s alter-ego revealed herself in the labyrinthine layers of intricate woodwork, weathered paint palettes and whimsical treehouse forms. They were floating, functioning works of art. In 2009, The Swimming Seas of Serenissima sent a similar flotilla drifting through Venice. Inspired by raft-builder Poppa Neutrino – who ‘scraprafted’ the Atlantic from New York City to Ireland – they traversed the Adriatic Sea, “always hugging the coast”, eventually dropping anchor at the Venice Biennale.

But even in a buoyant Bohemia, consensus is tricky. “That shit is fucking tiring,” says Callie, to the diverse group of activists at The Bank of Ideas. “But when you have an idea, and people say you’re going to fail, a lot of times its because they haven’t seen it happen before. And all that means is that there’s not a precedent for it. It doesn’t really mean it’s not possible, it just means that there isn’t an understanding for it and you need to create that understanding… When you are trying to do something and people tell you, ‘No,’ it’s not because they’re gonna stop you; they just don’t wanna be the one who gave you permission. Like, ‘I don’t wanna be the one who told you assholes that you could crash into a fucking bridge.’”

Callie balances her collaborative outdoor projects with solo installations in private spaces, and has spent years coming to terms with the code of ethics underpinning both approaches. “It’s amazing to bring people together in one place and draw dots between different ideas,” she explains. “But when I started to take people up on gallery invitations, I started to dream about building-out installations in a very complicated way. For that, you need a very safe, protected space – you need tools and all these things that being outside, or being on a boat on a river, doesn’t provide. You need that little bit of preciousness. Working inside is like a thought laboratory for me; it’s a really nurturing way to grow your ideas whereas when you’re out in the world, everything is challenging. It consumes so much of your mind and energy that you lose your ability to have this dreamy delicate thought process, and I would be lost without that.”

In world of self-promoting Twitter-heads, Callie doesn’t have a website; she is the best type of enigma – everywhere and nowhere all at once. As a character, Swoon may be a swashbuckling rebel – a Pied Piper figure to a crew of Lost Boys – but Caledonia Currie (who’s not afraid to tell her Occupy audience that she subsidises her projects with “really expensive artwork”) has a more tempered take. “I feel uncomfortable saying I’m definitely countercultural, because you just immediately become aware of the thousands of ways in which you’re totally part of the culture,” says Callie, pouring more sugar into coffee that’s now turned cold. “Most thoughtful people have this constant battle between trying to be happy in simple daily ways – appreciating things like a good meal, clean drinking water and a taxi ride somewhere – while understanding how something like the disaster in the Gulf and the oil industry leads back to our way of life. That feeling like your culture is implicitly, explicitly in every way just ravaging the earth and every culture that isn’t living like you do.”

She recently returned from central Brazil, where indigenous collectives are protesting the construction of the Belo Monte hydroelectric dam, a $10bn project that could displace 50,000 people. “There are massive amounts of chemicals being dumped into the rivers, their indigenous way of life is at stake – they’re being suffocated. Knowing that in the city you feel great because you can turn up the heat – I can’t recognise myself as not participating in that lifestyle but I’m constantly thinking, ‘I have to find a way to live differently.’ It’s not working yet, I can’t figure it out – it’s like not being able to think outside of this box. I’m really struggling with it, but I feel like that process maybe leads you somewhere – it’s just about trying to figure shit out.”

Brazil was one of many field trips Callie regularly undertakes anywhere the survival instinct brings people together: from the Umoja Village in Miami (a homeless settlement founded by Take The Land Back) to a group of bereaved mothers fighting female homicide in Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. “We have to think about how [this epidemic] is connected to our lives,” says tee-total Callie. “In the sense that it’s connected to the drug trade – just think about how that’s directed towards the US and Europe and our consumption. We can be so unaware of what goes into the things that are brought to us.” Working alongside the collective Nuestras Hijas de Regreso (‘May Our Daughters Return Home’), Swoon’s response was a portrait of victim Silvia Elena, surrounded by a rabble of papercut butterflies (symbolic of lost souls) and sound-tracked by audio interviews with many bereaved mothers.

But Callie’s not one to stand by and take notes. “Portraits like that are about raising awareness,” she says, “but I felt this need to make something that has a tangible impact.” In 2010, while studying architecture, she “hatched a plan” with collaborator Ben Wolf (whose scrapyard structures buttress many of Swoon’s shows) and started the Konbit Shelter project in post-earthquake Haiti. Using architect Nader Khalili’s Superadobe domes – a resource-light ‘earthbag’ construction used in humanitarian housing – they helped the local community construct their own buildings.

But as an outsider proposing a local solution, the learning curve was steeper than Callie foresaw. “We had to step back and remember, ‘You’re providing a service,” she says, deep furrows in her brow, “you’re learning something and then giving back. If at any point it feels wrong, then you don’t do it.’ Whereas on the river if people said, ‘You’re wrong,’ we were like, ‘Hell now, we can do this.’” After erecting a communal space, they embarked on a dome for a local woman called Monique, who was living under a tarpaulin with her newborn baby. “There are so many dangers with this process,” explains Callie. “It provides jobs and excitement and the local community is really gung-ho, but at the same time it’s one house for one person and you have to ask, ‘Is that weird? Will that single her out? And what does that mean about our relationship with her?’ There is all this stuff that I feel quite unresolved about that can only be resolved through our continued relationship. Now that we know each other better, we can ask, ‘Do you really like this style of architecture? What should the next step be? And how can it not include us as outsiders?’ In the end, it’s not really empowering for us to keep doing things – it’s about teaching and giving independence as a solution.”

Soon after we meet Callie will return to Haiti to “ask more questions and get real answers”, but she’s also applying these lessons closer to home. Before Haiti, she’ll stop in New Orleans to work on a “musical house” in a Hurricane-ravaged neighbourhood. And in Braddock, Pennsylvania, she and four other artists – “the same women who marched through Manhattan in paper tutus” – have taken over an abandoned church to start Transformazium, a community arts project in a poverty-line area that was largely abandoned after the steel industry collapsed, with the population falling from 15,000 to 5,000 since the 1940s. “I feel like I’m trying to get a hands-on understanding of how various communities are struggling for survival,” explains Callie. “The house in New Orleans is very much about psychological survival – being soulfully and spiritually stimulated by music and beautiful things. With Transformazium, it’s a question of, ‘What can we create in the wreckage of this situation that is beneficial to the community?’ The guys who live there full-time are pretty amazing in their dedication to create small responses and to really fit and be integral to the community – they are the community at this point. Next, we want to talk actively to people about their vision for the space. I would like to just start hundreds of conversations and not try to stick to any one thing.”

Having cleared our plates an hour ago, we decide it’s time to bid Abba farewell. Back at Black Rat Projects, a power-dressed art magazine editor stops by for a look, while a kid outside shouts something like, ‘Look, it’s a Swoon!’ Callie rolls up her sleeves, crouches down, and starts rolling up giant papercuts on the dust-covered floor.

For a woman who wants to start hundreds of conversations, Caledonia Currie and her invincible other half seem charmingly unaware of the trellis of charged dominoes they leave everywhere they go. “The idea of success has always been kind of nebulous to me,” she says. “When I was young, it seemed so unlikely that it was more freeing to not invest in that myth by saying, ‘Do what you want, whatever happens will happen, and let the things you make be your thing.’” Days before this article goes to press, an email will pop into my inbox entitled, ‘Do, make and create together meet up.’ The Occupy London activists are planning their next Swoon-inspired attack. And with that, the latticework grows.