Georgia O’Keeffe: A portrait of a woman ahead of her time

- Text by Miss Rosen

Georgia O’Keeffe is an American original, who created the life she wanted to live on her own terms, liberated from the constraints and constructs imposed on women during the first half of the 20th century. For over seven decades, O’Keeffe cultivated her public persona, challenging all aspects of the status quo, in order to live her truth in the eyes of the world.

Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style is the first exhibition to examine the relationship between the artist’s lifestyle and her work. Curated by Wanda M. Corn and assisted by coordinating curator Austen Barron Bailly, the exhibition features a selection of never-before-seen garments designed and created by O’Keeffe that became part of her signature look, along with iconic artworks and photographs by her husband Alfred Stieglitz, Cecil Beaton, Bruce Weber, Todd Webb, Arnold Newman, John Loengard, and Tony Vaccaro, among others.

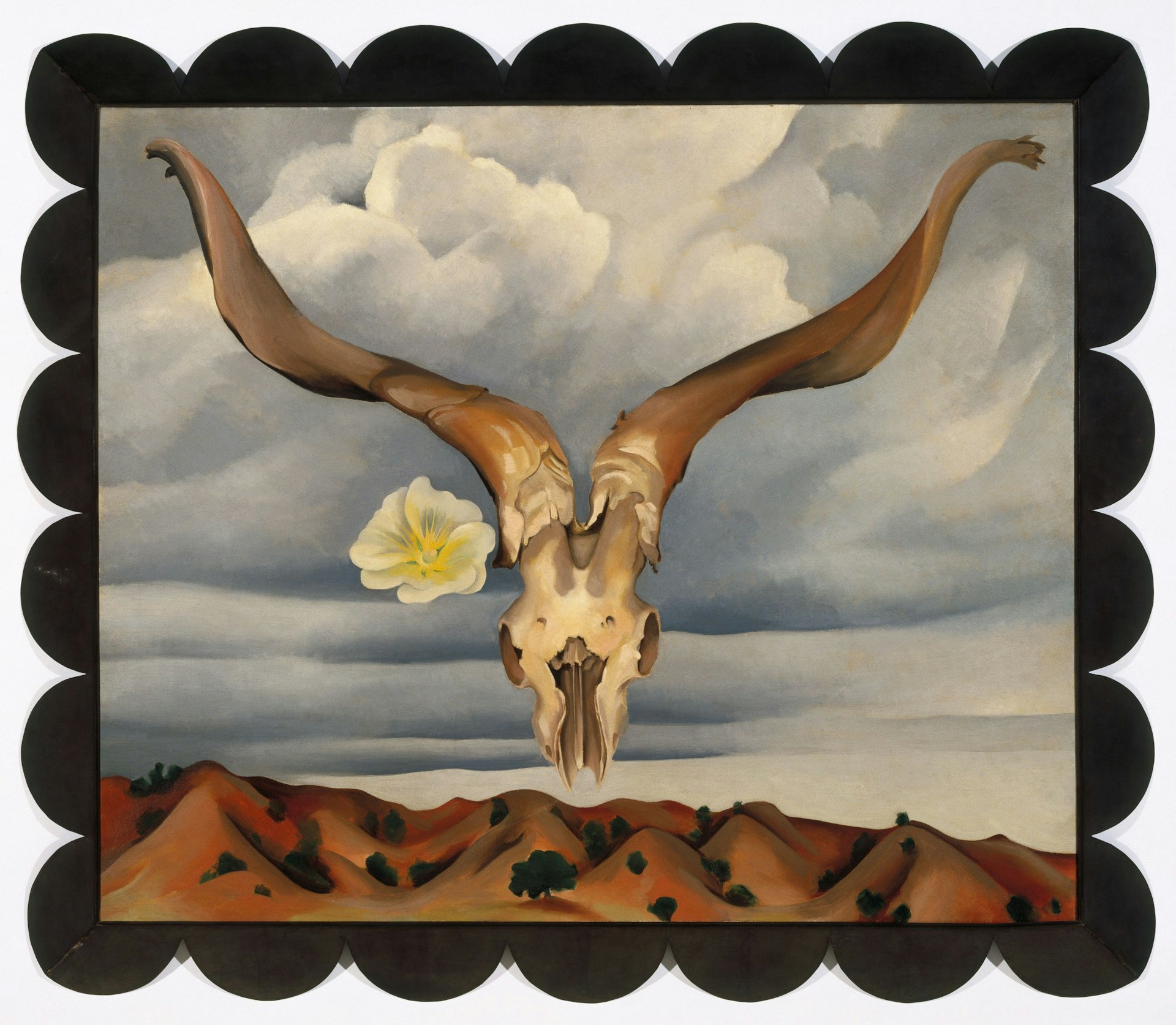

Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock–Hills (Ram’s Head and White Hollyhock, New Mexico), 1935. Brooklyn Museum; Bequest of Edith and Milton Lowenthal, 1992.11.28. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

“Georgia O’Keeffe was never afraid of standing out,” Barron Bailly observes. “She had a certain fearlessness and a conviction of who she was and what she needed to do to make the art she was called to make. This show demonstrates her identity as an independent, as someone who did not worry about fitting into a mainstream conception of what a woman should look like and how a woman should dress, of what and how a woman should paint.”

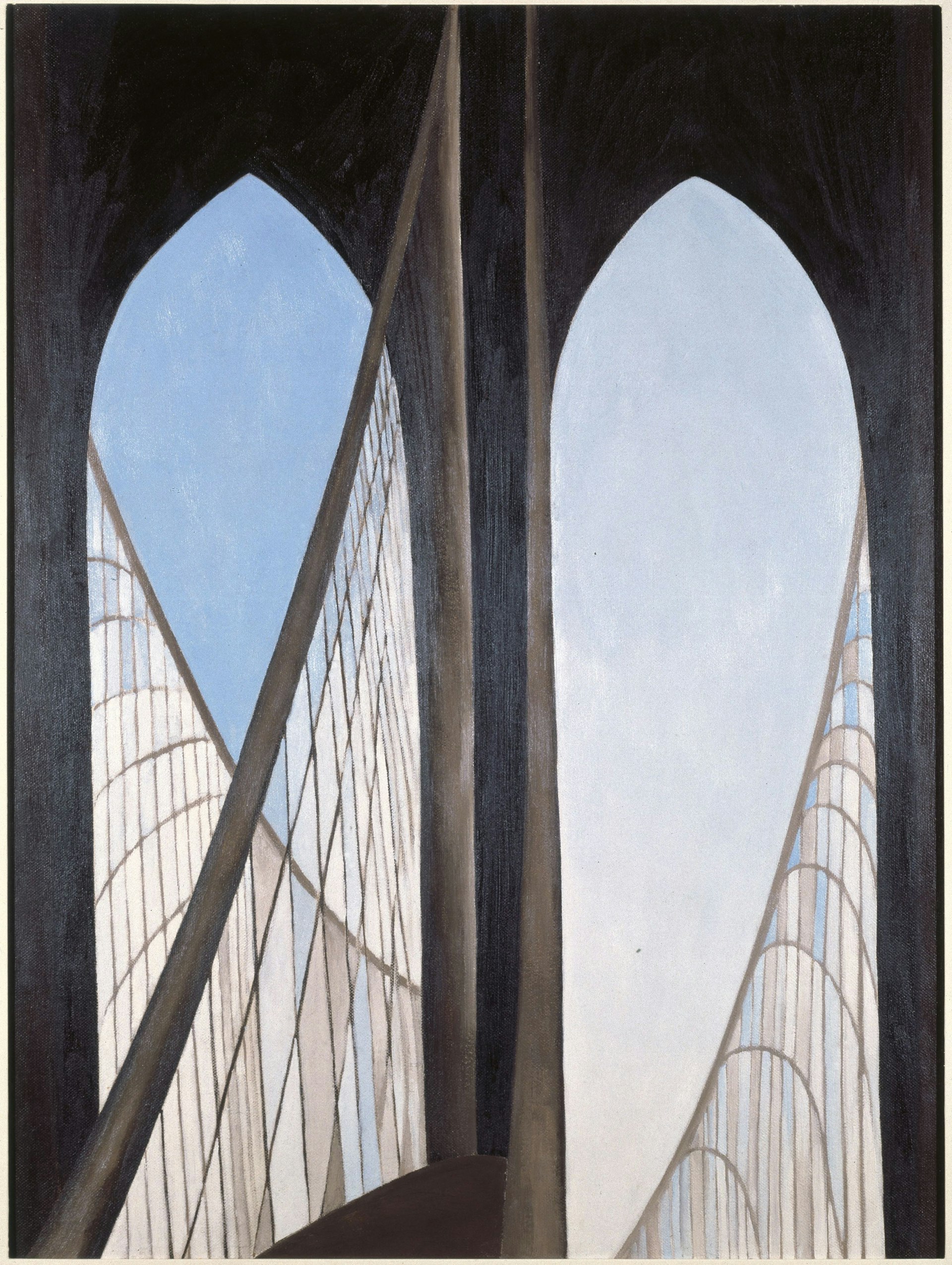

In the 1920s, when she first came to the attention of the art world, O’Keeffe broadly rejected the label of “woman artist,” which was put on her by male critics quick to marginalise an original aesthetic that pushed forward the boundaries of abstract art well ahead of her contemporaries. She rejected the strictures of gender in every element imaginable, from the clothing she designed and created, to her decision to keep her maiden name throughout her life.

Alfred Stieglitz (American, 1864–1946). Georgia O’Keeffe, 1929. National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.; Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1980.70.247. © Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington

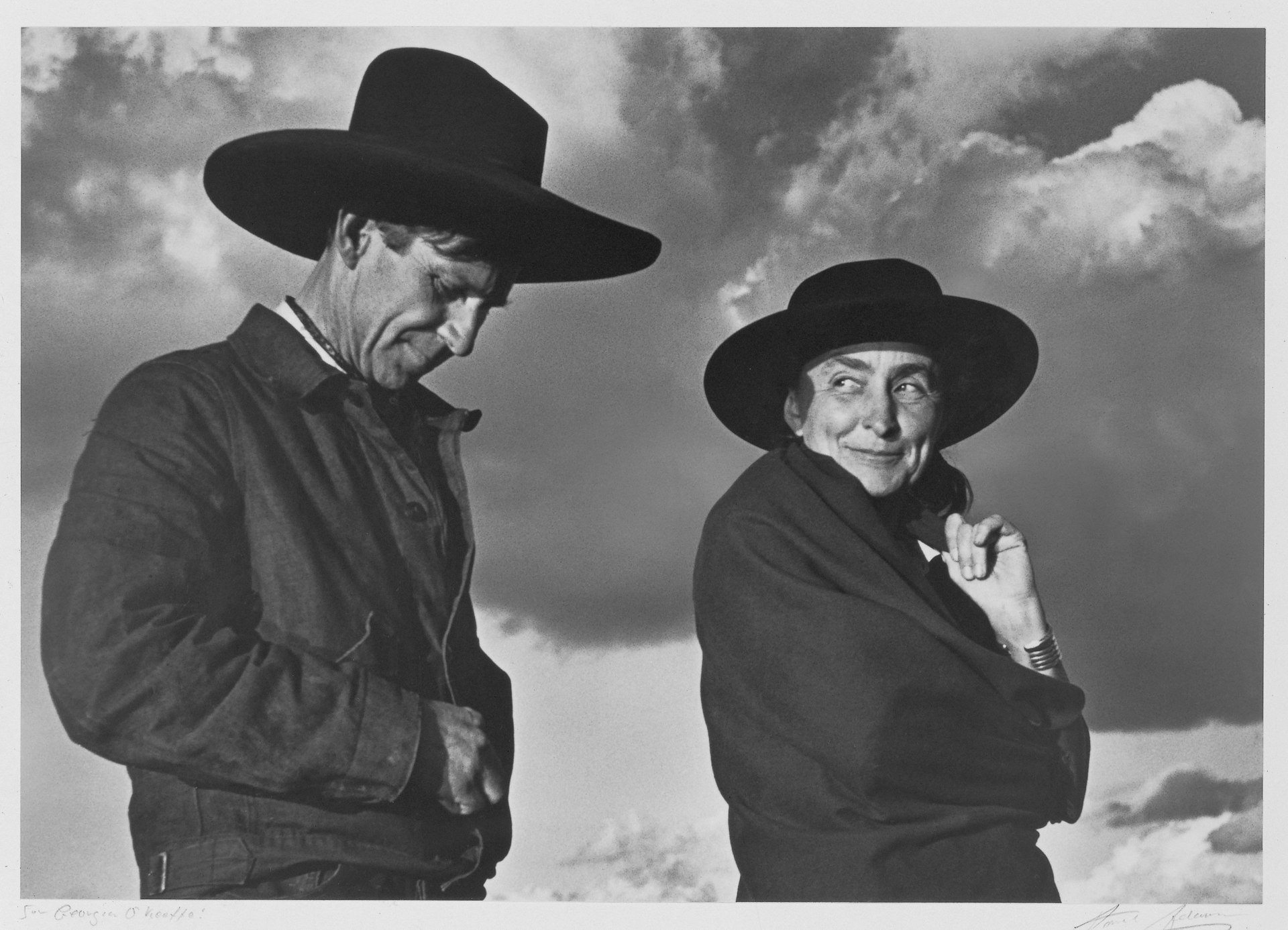

“O’Keeffe became famous for reinventing herself as a Southwest modernist,” Barron Bailly explains. “Her move to New Mexico was very radical. When she started needing more solitude and independence to do her best work, she began going out to New Mexico alone, not with her husband. She made two homes there over the years and her husband never visited her there. She made choices that had an effect on her personal life to be able to make the work she wanted to make.”

Wanda Corn used the phrase “iron discipline” to describe O’Keeffe’s adherence to her aesthetic vision and her creative life. “It’s a very kind of aspirational thing and incredibly hard to achieve,” Barron Bailly notes. “This idea of creating a public persona that has become the iconic image of the artist – that required a lot of work to maintain. All of this to facilitate to live the life she wanted to live. She was financially successful from the sales of her art and could do it.”

Since her death in 1986, O’Keeffe has become an established pioneer of American 20th-century modernism, and her work is finally free of gendered readings and labels. It’s no surprise – in a time of strict societal pressures, she did things her way.

Blue #2, 1916. Brooklyn Museum; Bequest of Mary T. Cockcroft, by exchange, 58.74. (Photo: Sarah DeSantis, Brooklyn Museum)

Ansel Adams (American, 1902–1984). Georgia O’Keeffe and Orville Cox, 1937. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.M.; Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 2006.06.1480. © 2016 The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust

Brooklyn Bridge, 1949. Brooklyn Museum; Bequest of Mary Childs Draper, 77.11. (Photo: Brooklyn Museum)

Georgia O’Keeffe, circa 1920– 22. Gelatin silver print, 41⁄2 x 31⁄2 in. (11.4 x 9 cm). Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, N.M.; Gift of The Georgia O’Keeffe Foundation, 2003.01.006. © Georgia O’Keeffe Museum

Georgia O’Keeffe: Art, Image, Style is on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. Massachusetts, through April 1, 2018. The catalogue, Georgia O’Keeffe: Living Modern, is available from Prestel.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.