The Malian photographer who shot Africa’s post-independence flow

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Malick Sidibé - courtesy Galerie MAGNIN-A, Paris

A childhood accident left Malick Sidibé blind in one eye, but that didn’t stop him seeing – and documenting – the energy of post-independence Mali. Before his death aged 80 in April 2016, he picked up the title “the eye of Bamako” and left a priceless record of African youth culture.

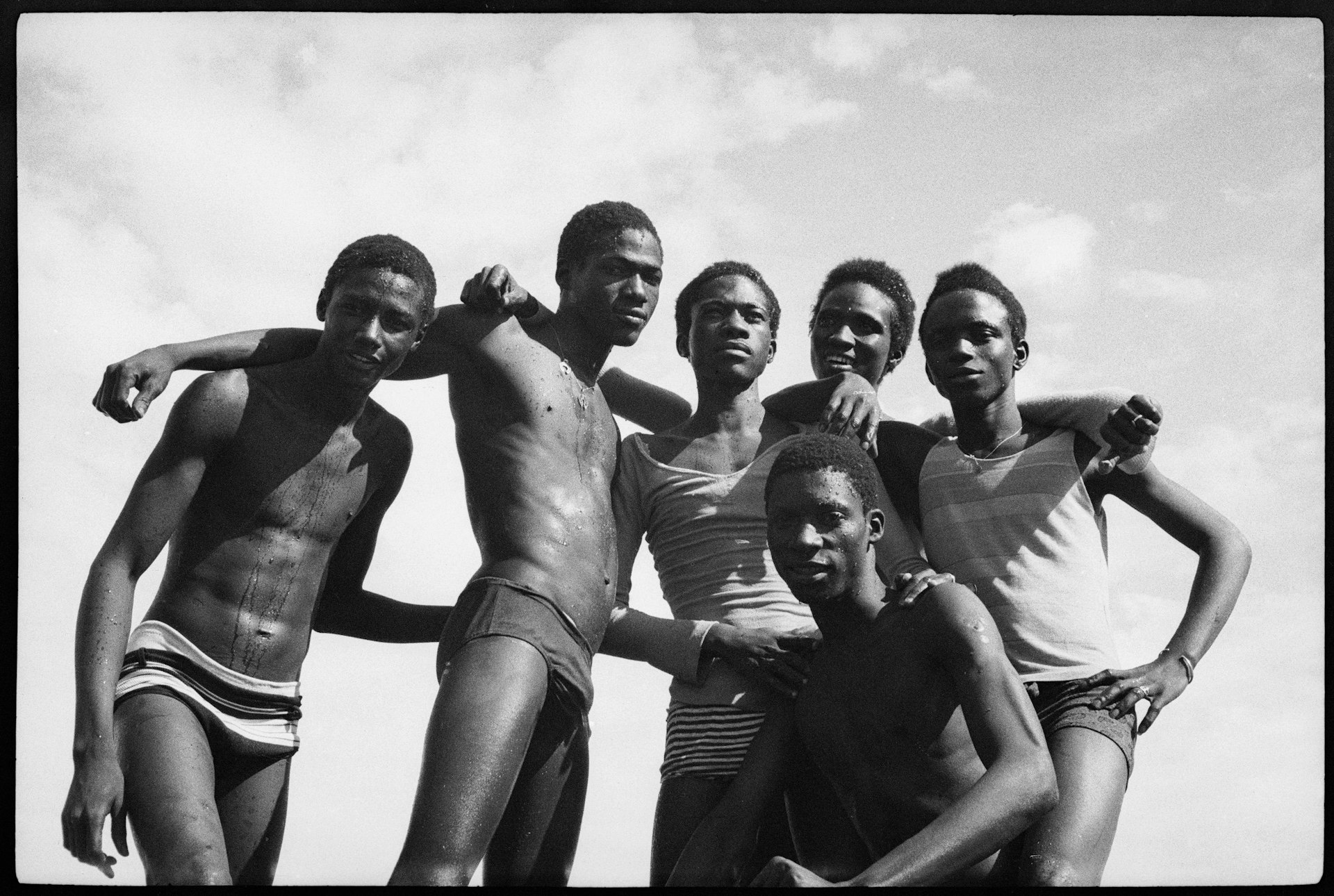

Les Retrouvailles au bord du fleuve Niger, 1974

Mali declared its independence from France in 1960, joining a wave of African countries that successfully freed themselves from their colonial oppressors during the 1950s and 1960s.

After founding Studio Malick in 1958, Sidibé established himself as Mali’s only travelling documentary photographer in the early 1960s. Travelling by bike, he was uniquely positioned to capture the burgeoning youth culture that accompanied independence.

He shot graduation celebrations, dances and beach parties across the country, but it was his images of well-dressed youths in the nightclubs of Mali’s capital, Bamako, that really captured the new post-independence groove.

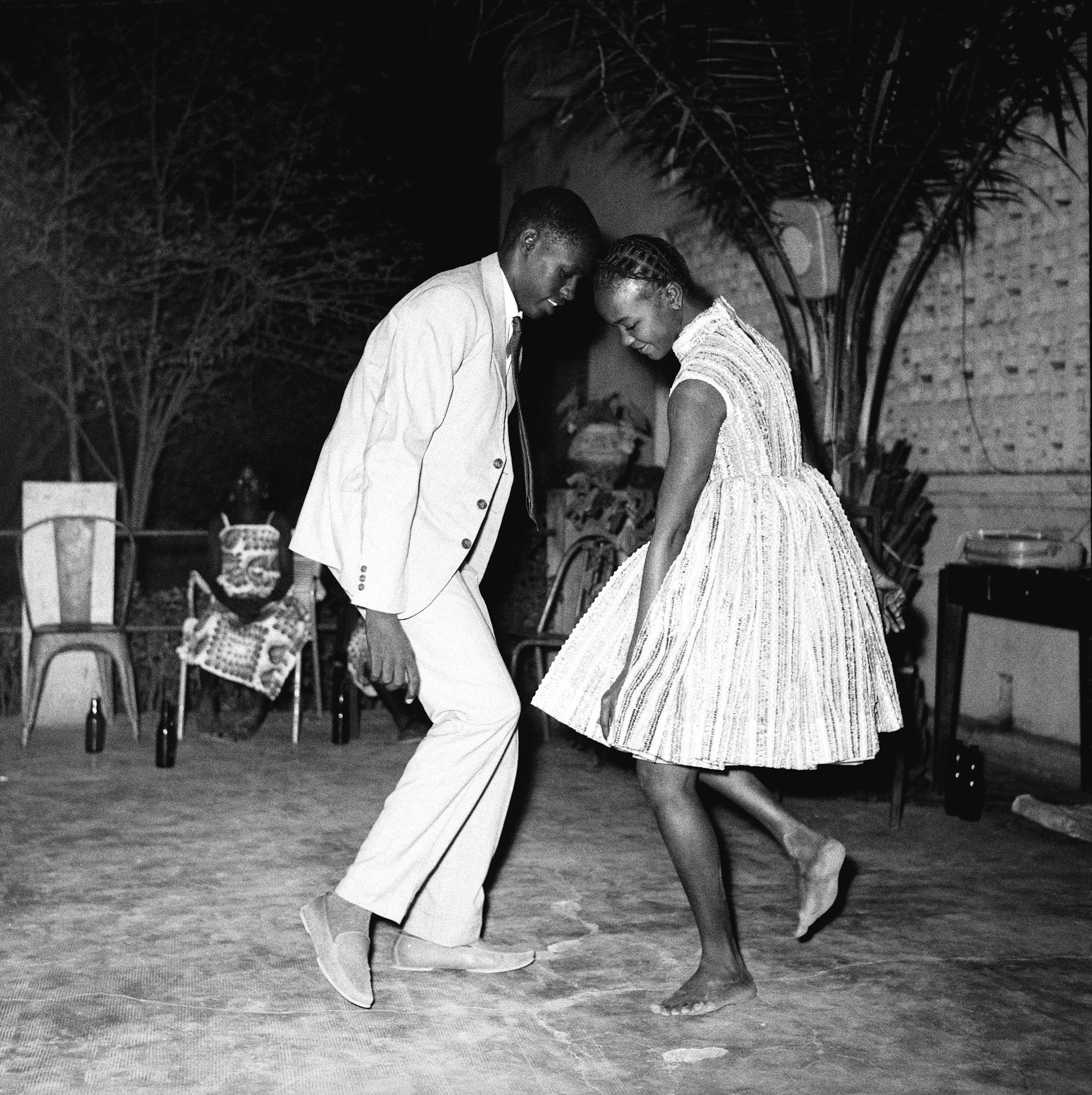

Nuit de Noël (Happy Club), 1963

Nuit du 31 Décembre, 1969

Immersing himself in the beat, often at the centre of the dance floor, his images of young, fun-loving couples reflected the newfound confidence of the nation and its soundtrack – imported pop, soul and rock’n’roll.

“Music was the real revolution,” Sibidé once reflected. “We were entering a new era, and people wanted to dance. Music freed us. Suddenly, young men could get close to young women, hold them in their hands. Before, it was not allowed. And everyone wanted to be photographed dancing up close.”

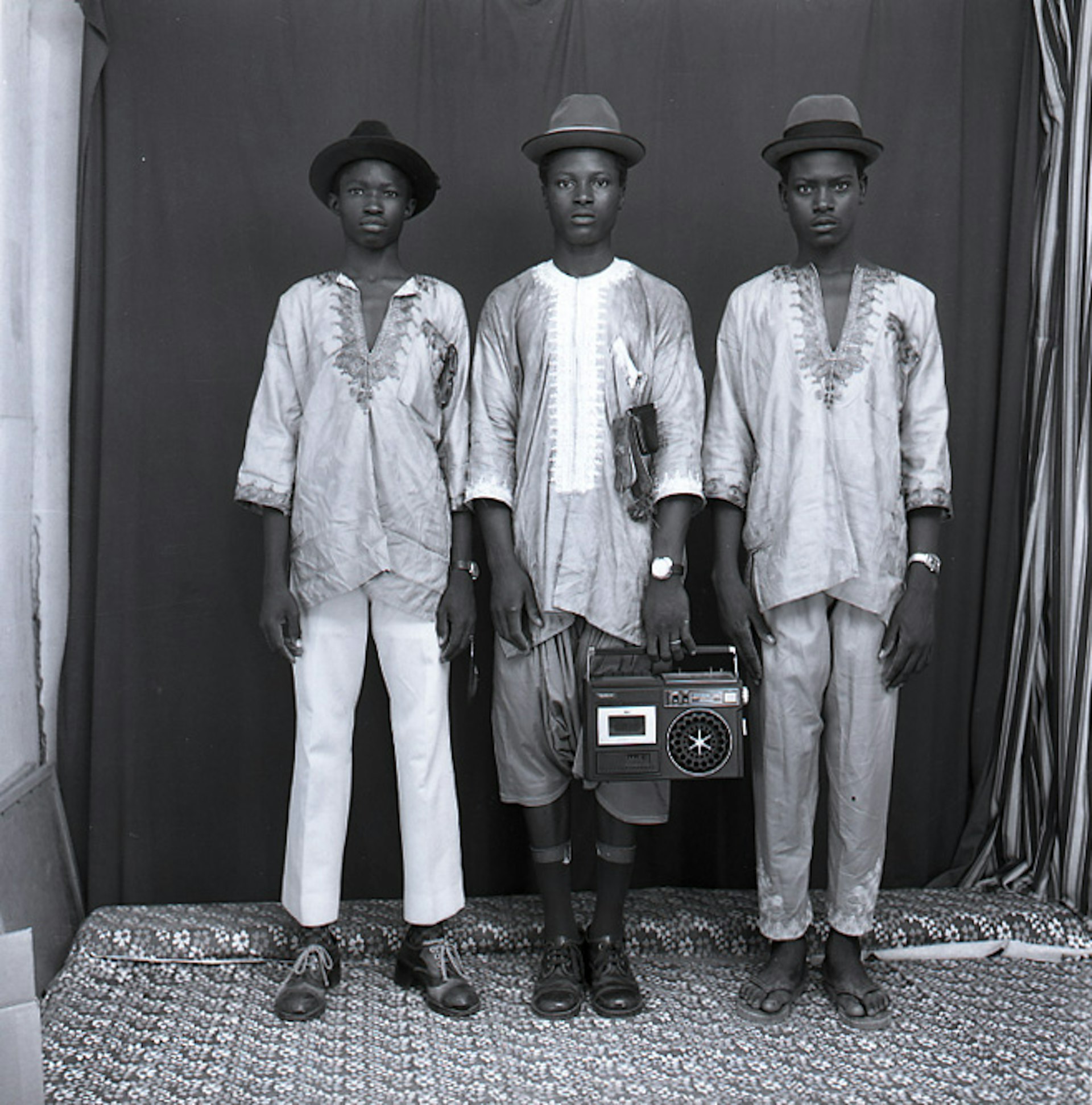

Sibidé is also remembered for his studio photography. “[Studio Malick] was like a place of make-believe,” he said. “People would pretend to be riding motorbikes, racing against each other. It was not like that at the other studios.”

Trained in drawing at the School of Sudanese Craftsmen (now the Institut National des Arts) in Bamako, Sidibé brought an artist’s eye for composition to his studio portraits, encouraging his subjects to bring energy and their own props, from new motorbikes to James Brown records or donkeys and goats.

A moi seul, 1978

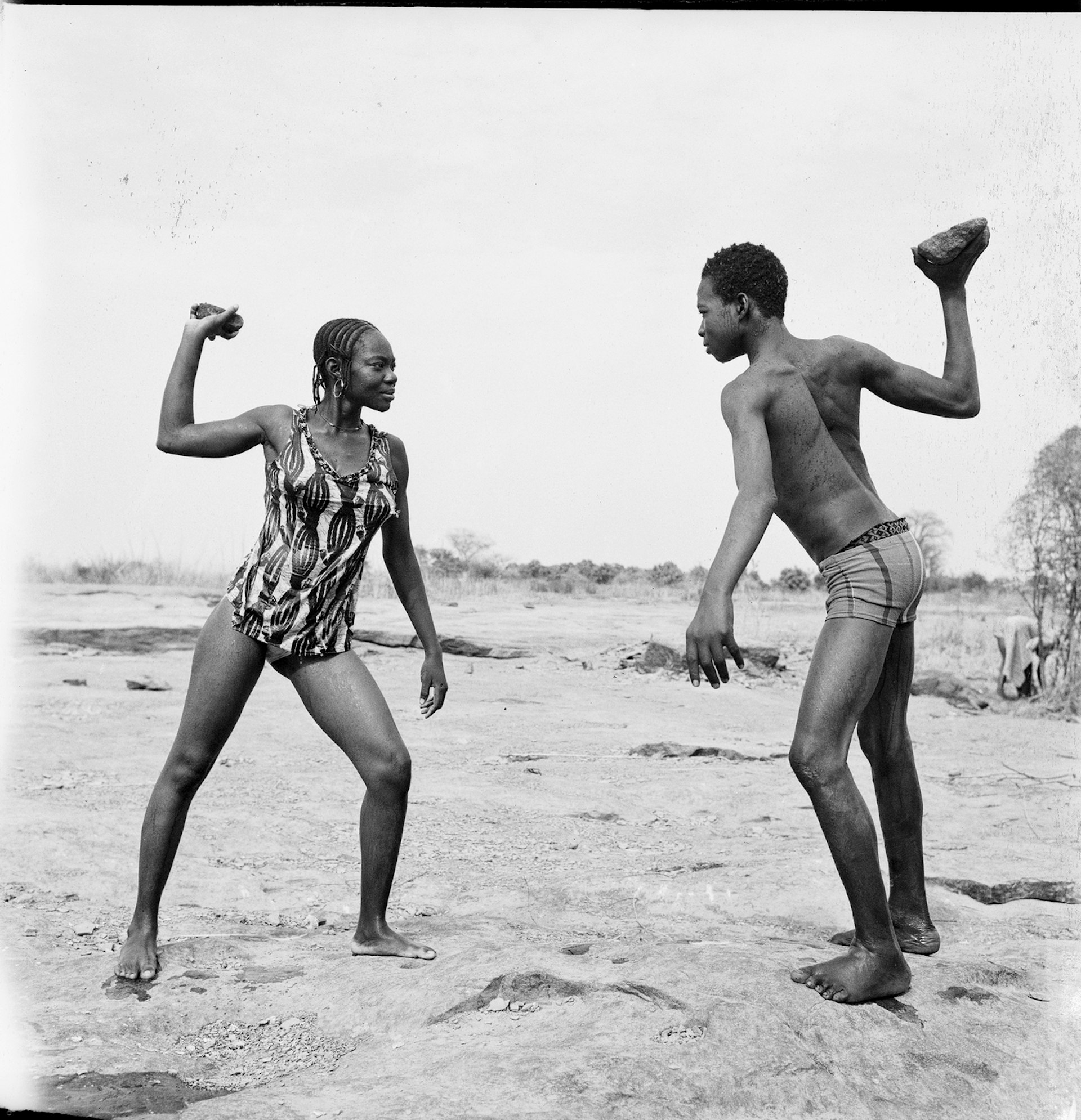

Les jeunes bergers peulhs, 1972

Sibidé’s work was “discovered” by the art world in the early ‘90s after Malian musicians such as Salif Keïta and Ali Farka Touré put Mali on the map for Western audiences. His photography has since been shown worldwide, but his posthumous show at 1:54 Contemporary African Art Fair in London represents his first UK solo exhibition.

Combat des amis avec pierres, 1976

Malick Sidibé: The Eye of Modern Mali is at Somerset House until 15 January 2017.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.