How one of the UK’s most acclaimed MCs is moving into new genres

- Text by Isaac Muk

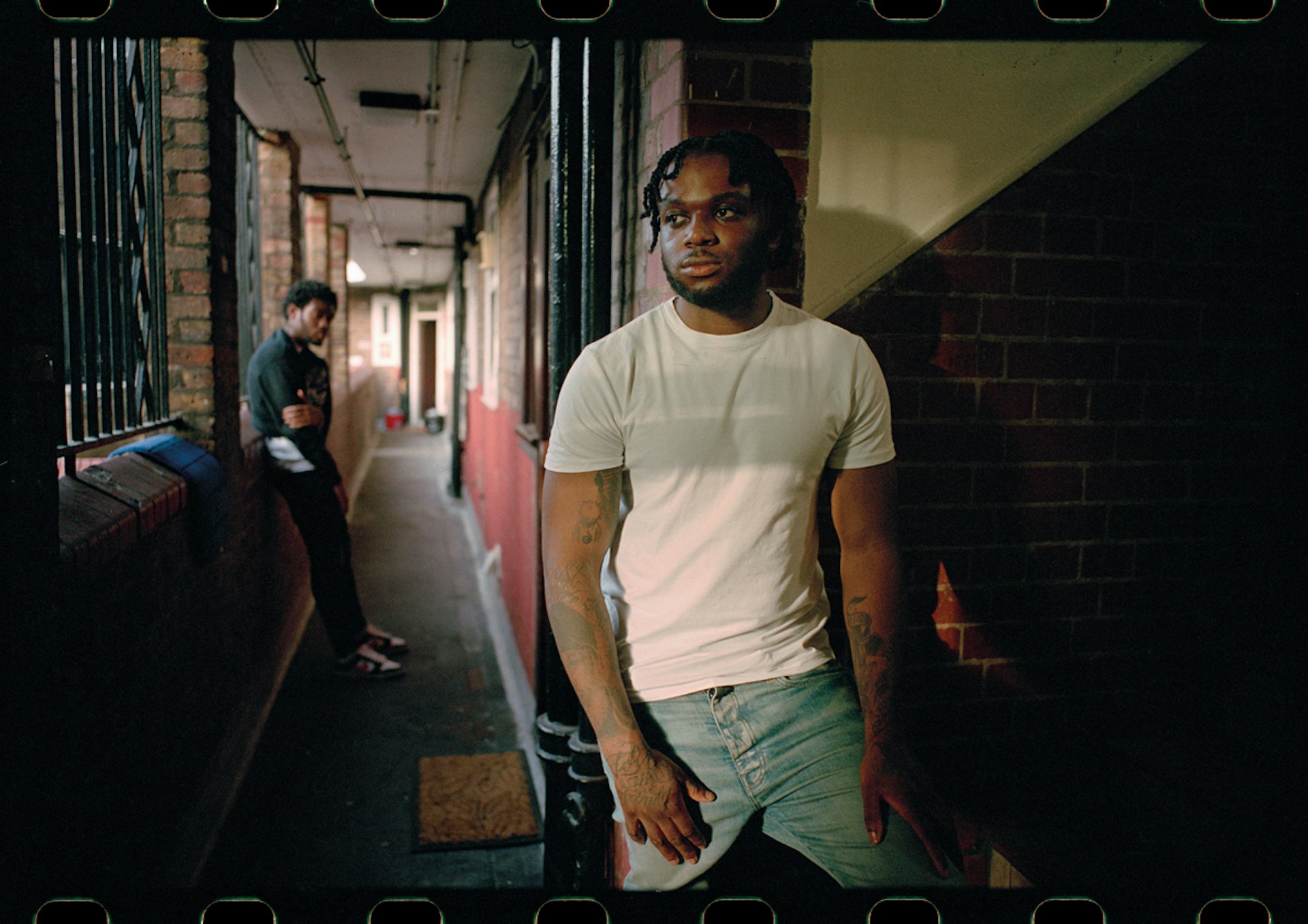

- Photography by Simon Wheatley

The Lower Third is an intimate, low-ceilinged basement set under London’s Denmark Street, a historically musical location. Putting on sunglasses, as a flurry of smartphone cameras flash him, Blanco, one of London’s finest MCs, addresses the roughly 200 fans shortly after taking to the stage for the launch party of his new mixtape, ReBourne.

“I’ve been waiting,” the rapper tells the crowd, signalling to the DJ with a glance and launching into a raucous rendition of Londis – a single from the LP – followed by a slew of fresh tracks from the tape and a handful of unreleased exclusives. Those short three words, while simple and potentially meaningless, provide a glimpse into the double and sometimes triple meanings that have come to define the complex and singular style of lyricism that populates Blanco’s music – he’d been waiting to perform that night, waiting to drop his first tape in two years, and waiting to perform live in London for the first time in over two years.

“Yeah yeah, I enjoyed it – it was fun,” Blanco says the next day, while eating a bagel at a café in Kennington, South London, where he grew up. He’s performance-shy, having cancelled a tour following the release of 2021 LP City of God. A quiet and thoughtful character, Blanco doesn’t enjoy being the centre of attention, a far cry from the often swaggering stereotypes of rappers. “I want to do more shows, but I want to grow. Maybe a couple more smaller ones, then a bigger one – I want my shows to actually be a place people want to come to as a motive.”

We’re chatting a few days after ReBourne’s release, his second solo LP and the follow-up to City of God. The 12-tracker is a diverse, assertive journey through a range of styles and oddball productions, from the summery Ghanaian Afrobeats of Unruly ft. AratheJay, and the saxophone-led, stripped-back Brazilian baile funk on Brilliant Mind, to the retro-leaning hip-hop influenced Kojey Radical collaboration The Long Way.

With watertight flow throughout, it feels like something of a coming-of-age LP, and now aged 24, Blanco is unafraid to push his music in directions no one expects. “I like listening to new sounds and being like ‘this could work – this sample could be sick’,” he says. “I always do that. I’ll just experiment and then go with the [beats] that sound good, or I feel people enjoy.” While distinctively Blanco, the body of work marks the artist’s further progression since bursting onto the UK rap scene seven years ago as a key member of pioneering drill crew, Harlem Spartans, and another step away from the genre that defined his younger years.

Blanco started making music after visiting a youth centre near his home in Kennington. One afternoon, his friends Bis and Zico invited him into the building’s music studio, where they were laying down bars over some samples they had picked out. “I went there and said ‘yeah, I’m gonna try something’,” he says. “I tried it – the mandem said ‘we see suttin here’… and the rest is history.”

Harlem Spartans was formed. Along with Bis and Zico, Blanco was joined by several other talented young Kennington rappers including Loski, MizOrMac, SA aka Latz, TG Millian, and Active aka Aydee. Their sound: the dark, menacing, bass-heavy drill that had started to make waves in the underground and on the estates of London – influenced by the nascent sounds of early 2010s Chicago when artists including Chief Keef and Pop Smoke took trap and twisted it into the music and voice of a new generation of inner city, working-class, mostly black youth on both sides of the Atlantic.

Within a year, Harlem Spartans’ music gained serious traction, with their lo-fi music videos reaching hundreds of thousands, then millions of views on YouTube, as now genre-classics Kennington Where it Started and Call Me a Spartan propelled them to the forefront of the capital’s drill scene. And they weren’t the only ones – groups like 67 and 410 from Brixton, OFB in Tottenham, 1011 in Ladbroke Grove and Zone 2 in Peckham were also carving out their own niches within the genre.

With violent lyrics that frequently taunted other gangs and artists, referencing weapons, and videos of youths in balaclavas rapping to camera – the genre became the centre of a media, political, and policing panic and scapegoating. In 2018, Labour MP Harriet Harman said: “With the crime that’s happening now, music does influence it… The lyrics glorify gang warfare and include threats against rival gangs or individuals.” The uproar essentially led to drill’s censorship, with the Met Police shutting down live shows and working with YouTube to remove music videos from the platform (which has at times affected Harlem Spartans).

“...everyone has their own struggles, but in a group you talk about stuff everyone can relate to.”

Like their contemporaries, Harlem did reference gang violence and weapons in their lyrics, but Blanco doesn’t see them as particularly meaningful. “People love the old me, but I don’t really,” he reflects on some of his early verses. “I just feel like I didn’t really have much to say – I would just say anything.” Part of that came from being in a musical group. “You talk about broader stuff, because everyone’s different, everyone has their own struggles, but in a group you talk about stuff everyone can relate to.”

While Harlem Spartans were flying high on YouTube and SoundCloud, on the ground their lives had hardly changed. “It was difficult, they didn’t let us do shows and stuff – I don’t know what it was, an embargo?” Blanco asks. “But [at our] shows the police would always lock it off, so no money from shows. The money we should have seen from music – we weren’t really seeing it. And were we getting label offers as well? Not really.”

The music should have offered these young talents a path to success. “TG’s brother was talking about Spotify, PRS, and moving out of the ends, like getting a mansion,” Blanco says, before a pause. “Would have been a crazy household.” But the barriers placed in front of the group would prove to be too high. In February 2017, police pulled over a car that Blanco and MizOrMac were riding in as they were on the way to a music shoot, reportedly finding a samurai sword, body armour, and a loaded gun. They would be sentenced to three-and-a-half years and six years in prison respectively.

It was just as the group felt on the brink of breaking into the mainstream, with US superstar rapper Drake quoting Bis’s lyrics on Snapchat: “Question… if gang pull up, are you gonna back your bredrin?”

“I was pissed,” Blanco remembers of when he heard about the shoutout. “I’d just landed in jail – I was like ‘ah, fuck’.” Harlem Spartans would never quite hit the same heights again. TG Millian, MizOrMac and Loski are currently serving time in prison, while Latz and Bis were both stabbed to death. It’s a deeply tragic story of a talented, pioneering group of young men who were consumed by the uncompromising world around them.

Away from everything happening in London, Blanco spent his time inside incessantly writing bars – laying the foundations for the solo career path he’s on now and expanding away from drill. “I was honing my skills,” he explains. “Because rap is like any other thing, you just got to practise – the more you write, you get better, innit. [Jail] made me a better rapper, it made me wiser, I didn’t really think before I did something but now I can think through it.”

After securing an early release in 2018, Blanco signed with major label Polydor, releasing EP English Dubbed in 2019, and City of God before going independent for ReBourne. He started experimenting with baile funk – a natural progression for him having grown up speaking Portuguese as a result of his Angolan parents. “I just got bored of [drill] really,” he explains. “It didn’t feel like the same thing by yourself, so I don’t really have that passion for it. It made sense when I was in a group but didn’t doing it solo.”

On the subject of Blanco’s change of sound, “people love to moan about the lack of artists’ development [in music],” says Ian McQuaid, author of Woosh the UK’s first drill book, published last year. McQuaid also gave evidence in Blanco’s trial, testifying to his career as a musician. “It’s an incredibly unobvious thing to start leaning into, sort of Latin lounge music as your foundation and aesthetic sound palette. And it’s worked.”

The aforementioned single Londis sees Blanco open by reflecting on his time in prison. Over a cinematic, stringed intro, he spits: “Should’ve been in Dubai, instead I’m in Lockwood / That’s one stop Londis”. It’s an insight into his layered use of English – in two lines he references the HM Lockwood prison that he was jailed in, as well as an inner-city corner store that will hold plenty of meaning to thousands up and down the UK. With it being a ‘one stop’ shop, he’s also stating that he will not be found in prison again.

Throughout the track the range in his lyrical language is fully on show. There’s a reference to TG Millian being assaulted in prison “Hell in the cell, 2v1 / That’s handicap”, and later in the first verse, he references Green Goblin: “8 balls in the bag, what’s all this fondling? Aydee, Green Goblin.” Film and Japanese animé references populate his writing dating back to 2016 – he confesses to watching a lot of Netflix – and have since become something of a trademark. The LP’s title itself is a nod to the Bourne action movie franchise – a reference that has popped up in several of his tracks since 2016 solo track ‘Jason Bourne’. “From then on, people started calling me ‘Bourne’, and the track was a hit,” he says. “I used to love the movies and it just kind of stuck.”

“With the lyrics, there’s substance to them when I want to. I choose whether to leave it out, go a bit deeper, or just be as shallow as possible”

From these film shoutouts to calls to free his friends from jail, and even weapon and drug innuendos – Blanco has always rapped about the world around him as a young man from an inner-city estate. “With the lyrics, there’s substance to them when I want to,” he explains. “I choose whether to leave it out, go a bit deeper, or just be as shallow as possible.”

“I think he’s one of the best MCs active in the UK at the moment,” McQuaid says. “The lyrics are intricate – he’s spilling things out with a mad code that would take someone to approach them in an academic way to pull apart all the various levels of meaning.”

Perhaps the most personal track of all on the tape, ‘Son of a Refugee’, sees him explore his family’s past: “Son of a refugee / Had holes in my boat when they rescued me.” Over an introspective piano arrangement and a bass-heavy beat, the words are reflective and intimate. “Fleeing a war I’m escaping mine / Night terrors at breakfast time”. Blanco’s father sought refuge in the UK after fleeing the Angolan Civil War, which began in 1975 and continued intermittently until 2002. “My dad used to tell me stories about when he came to the country,” he explains. “So I thought it would be cool.”

The track feels particularly topical given the UK’s current treatment of refugees and the panic over ‘small boats’, which seems to entail either ‘housing’ asylum seekers in tight quarters on a giant barge or attempting deportation to Rwanda. He assures me that he wasn’t thinking about the politics when he wrote it, but how does it make him feel? “I’ll be real, it’s mad. Especially the way some of the [refugees] have been referred to in the news – one time [right-wing commentator Katie Hopkins] referred to them as ‘cockroaches’.”

Having now fully established himself as a solo artist, it perhaps makes sense for him to be reflective. While he’s moved on from making drill records and he sees a different artist in himself today, those tracks from six or seven years ago still hold plenty of meaning. Closing out The Lower Third show, surrounded by friends and collaborators, he performed a selection of crowd-frenzying Harlem Spartans classics including ‘Kennington Where It Started’ and ‘Call Me a Spartan’.

“You know every time I hear them, it changes,” he says of what the old classics mean to him now. “Before when I used to hear ‘Call Me a Spartan’ my favourite bit was maybe MizOrMac’s. But it’s changed, it’s deeper. I feel it when I’m on stage, I felt it yesterday – I just remember certain things because my brain kind of distanced itself from them times, like I was there but it wasn’t really me. But that’s why yesterday was cool.”

He's already working on new music, which he hints will pick up right where ‘Son of a Refugee’ leaves off. “I feel like my next project is going to be more origin-orientated,” Blanco explains. “It’s going to be more about my life.”

It’s a common cliché to say that we need to be able to look back to move forwards, but while he’s always travelling forwards with his beats and music, he’s ready to look in the rear-view with his words. So given the context, what does ReBourne mean to him?

“Really and truly – it’s just another chapter.”

This piece appeared in Huck #80. Get your copy here.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.

Support stories like this by becoming a member of Club Huck.