The film painting an unflinching portrait of county lines

- Text by Isaac Muk

It’s approaching dinner time in London, and Femi Oyeniran has managed to sneak away from the chaos. He takes a seat in his dressing room, situated two floors above the expansive, 2,000 capacity main room of HERE at Outernet, where producers and venue staff are hurriedly putting the final touches to installations, lighting, sound, and the red carpet. The premiere of TRAPPING – a new feature film that he co-produced alongside his Fan Studios business partner Nicky ‘Slimting’ Walker – is set to kick off in less than an hour, and there’s a hectic, electric energy in the air.

“Had to get some Air Force Ones,” he says with a wry smile, before pointing to a takeaway box of Nando’s. “Mind if I eat this by the way?”

With a loose dress policy where trainers and tracksuits are equally embraced alongside smart shoes, high heels, and suits, this is no ordinary film premiere. Side-by-side with some of the UK’s brightest cultural talents – with the likes of Top Boy star Ashley Walters and UK rap royalty Headie One expected to be in attendance – members of the general public have been given the opportunity to grab tickets of their own to the event.

“It’s something different, the approach that we’ve tried to take with the premiere,” Femi explains. “I didn’t want to do a conventional sit-down premiere. I wanted something that accommodated a lot of people because I’m not elitist. I don’t really like industry things, and I want people to have access.”

He’s in a good position to pass judgement on the film world, having been in and around the industry for close to two decades now – his breakthrough coming in 2006 playing the role of Moony in cult classic Kidulthood. Since then, he’s built a diverse and successful career in front of and behind the camera, spanning acting, directing and production. His latest venture, released via his and business partner Nicky’s new pay-per-view streaming platform The Drop and directed by Penny Woolcock, sees a baby-faced teenager named Daz (played by Louis Ede) go “OT” (out of town) to work in a county lines drug dealing operation – drug networks that operate across administrative boundaries. There, he finds himself stationed in a trap house along with a group of heroin addicts, quickly realising that drug dealing is not quite the money-spinning lifestyle that he initially imagined.

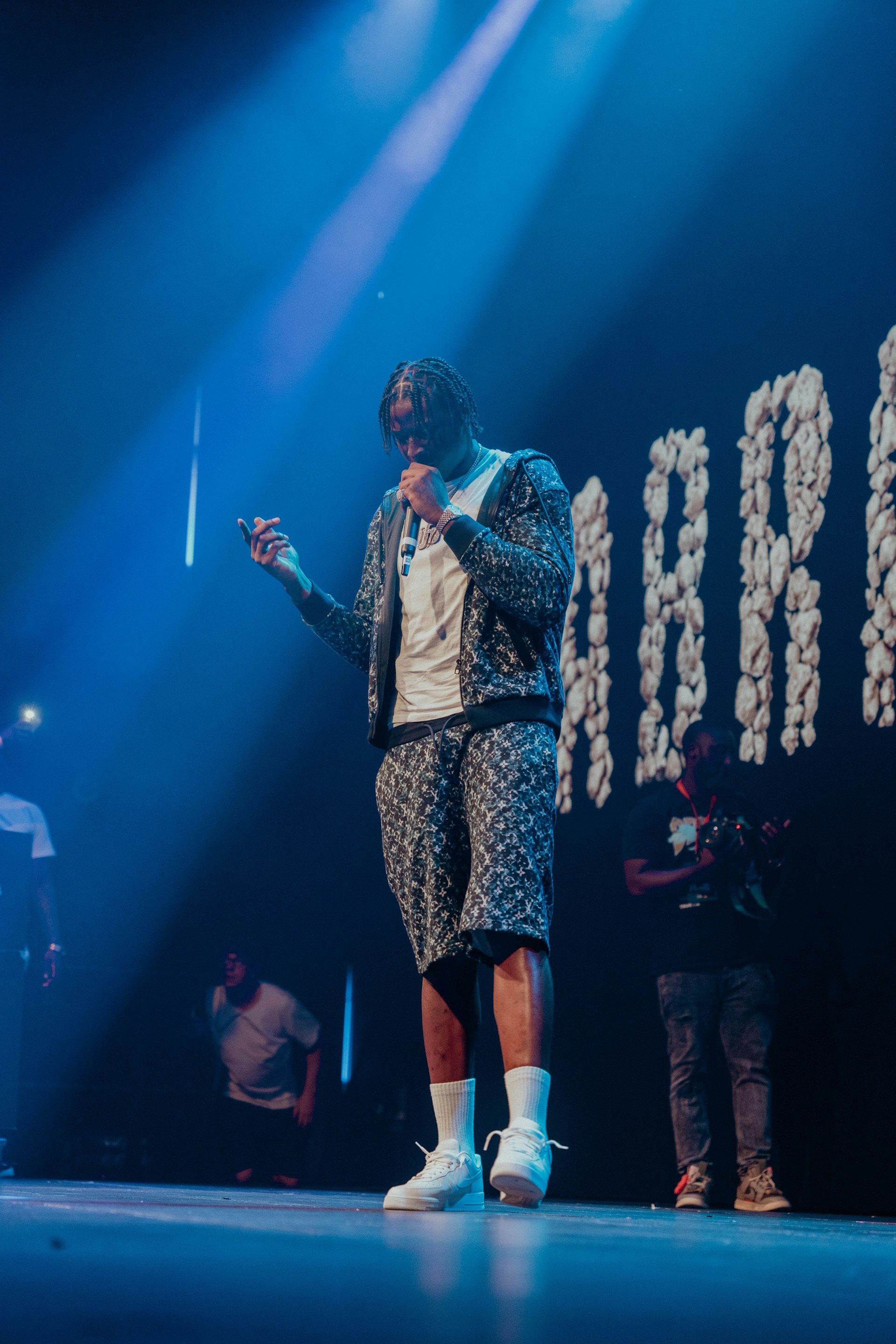

Spurred by the “need to put food on my plate for my mum” and repay a £50 debt that his brother owed before being sent to prison, Daz finds himself overseen by Magic, played by Tottenham-hailing rapper and OFB member Abra Cadabra. It’s a confident debut acting role, while also showing off his musical chops by creating the movie’s soundtrack. Given his profile, it is wild to think that tonight, performing at the premiere will be his first London solo show. After years of the Metropolitan police censoring drill musicians and shutting down their shows, tonight will be his chance to step out on his own.

Back above the throng, talk has turned to the long journey to bring TRAPPING to life. Femi was first shown the script by Penny, the film’s director, half a decade ago now in 2018. She explained that she had been working on the script with Dylan Duffus – who plays Bigman in the film – which was loosely based around Dylan’s experiences growing up. “I read it and it made me feel disturbed,” Femi recalls. “I felt disgusted, I felt the content – I read lots of scripts. Most scripts don’t make me feel anything – this made me feel something.”

The film opens with Daz in the Broadwater Farm estate in Tottenham, where he’s confronted by a group rapping over a drill beat. The area was made infamous after the explosive 1985 riots in the aftermath of death of Cynthia Jarret following a police raid on her house. “It’s a poverty-stricken estate, and it’s an area of Tottenham that hasn’t been gentrified yet,” Femi says. “As a part of that, you see crazy things – fun things, I grew up on an estate as well. There’s fun to be had, but there’s always danger round the corner and county lines is part of that. You’re always only one conversation away from getting in trouble.”

Yet it’s also a breeding ground for talent. Abra Cadabra grew up on ‘The Farm’, as did his fellow OFB rappers Headie One and Bandokay, the son of Mark Duggan who was fatally shot by police in 2011, sparking riots across the country. “There’s like 20 rappers from Broadwater Farm,” says Femi, excitedly. “These guys have managed to carve a way out for themselves. I love music, man – I think it’s very important. It’s one of the art forms that is accepted that Black people are good at, so it’s almost like one of the things within the mainstream that we’re legitimately allowed to have.”

Outside of the inner-city estates, TRAPPING also shines a light on the scale of drug use across British society. One scene sees Daz make “special deliveries” to giant countryside houses, where well-to-do families buy drugs from him. “The movie shows that [county lines] is not just a working-class problem,” Femi says. “It’s [also] a middle-class problem, and it also shows that actually when you’re not from [a working-class] background, sometimes you just get away with it.”

Other films and television shows that focus the lens on drug dealing and crime within the UK have been accused of glorifying gang culture. Whether you think the criticism is fair or not, no such arguments can be made about TRAPPING. From the opening salvos of the film, there’s uncompromising scenes of drug use and brutal violence in what is a disquieting portrait of county lines in the UK, and its effects on young people around the country. “I don’t think we’re glorifying it as a path for young people to take,” Femi says. “Whatever person watches this and decides ‘I want to sell drugs’, they need real help, real support.”

In recent years, the term ‘county lines’ has become something of a buzzword, particularly in political speak. The issue has been used in recent times to justify increasing policing resources and pressure on already overpoliced communities. In October 2022, a so-called “intensification week” saw 1,360 people arrested, with Home Secretary Suella Braverman commenting at the time: “County lines bring violence and misery to communities across the country, and it is vital we stamp them out.

“I welcome these recent operational successes, and we are continuing to support these impressive operations by providing up to £145m over the next three years through our County Lines programme,” she continued.

But Femi isn’t convinced such tactics and language – of focusing resources towards clamping down and hardening criminalisation, will solve the root causes of the issues. “They’re foolish, because they created the problem,” he asserts about those at the head of government. “They created the circumstances for these problems to exist. I grew up at a time when there were youth clubs, and they were well-funded. By limiting funding to these organisations, you create a situation where young people have nowhere to go, where young people have no support outside of school if they’re from a deprived background, so politicians need to bear responsibility for what’s going on rather than trying to shift the bark onto young people themselves. How can young people be the victim and the problem?”

There can be no denying that county lines is a serious issue in the UK, particularly in relation to young people. Children and teenagers are often recruited into moving and selling drugs because they are deemed to be less likely to be stopped and searched by police. According to Home Office figures, an estimated 27,000 children are involved in county lines, while the Children’s Society predicts that 4,000 teenagers in London alone are being “criminally exploited”.

As Femi says, it's a situation that has as much to do with the stripping of youth funding and other public services, as rising poverty among the most vulnerable in society. Government austerity over the past 13 years has led to lower wages for public sector workers, while cuts to welfare and benefit payments have left millions with less money in their pockets, all against a backdrop of a cost of living crisis driven by rapid rises in inflation.

Millions are desperately trying to keep their heads above the poverty line. It means that there is less money for parents to keep their children properly fed, and less time to ensure they are staying out of trouble. An Observer report from December warned that county lines gangs were “using burgers and warm coats to recruit hungry, cold children”.

But there’s the chance to tackle some of the issues at the highest echelons of power, with a panel discussion taking place inside the House of Commons to discuss county lines and other themes in the film. “We can’t just be having a conversation down here,” Femi says, anticipating the opportunity to spotlight the issues. “We need to be having it up there. It’s important. We need to be challenging the powers that be to enact change.”

Two days later, the discussion takes place in a Parliament committee room, reached after going through airport-style security and passing several marble statues of former Prime Ministers in the grand, gothic, corridors of power. At the head of the room sits Femi, Abra, panel chair Bell Ribeiro-Addy MP for Streatham, CEO of Enact Equality L’Myah Sherae, youth coach and campaigner Amani Simpson, and Power The Fight founder Ben Lindsay OBE.

Over two-and-a-half-hours, the panel discuss the impact of poverty on the increasing numbers of children involved in criminal gangs, how drug criminalisation and the ‘War on Drugs’ has only exacerbated crime, and the disproportionate effects of harsh policing on ethnic minorities. “Black and Asian people are 240 per cent more likely to receive a prison sentence than their black counterparts,” L’Myah says. “In regard to drug offences again, only eight per cent of white suspects are actually arrested, whereas 18 per cent of Black suspects are arrested. The stats are super clear.”

When speaking about TRAPPING, Amani and Femi explain how they have had conversations about collaborating and using the project to teach children about the dangers of becoming involved in county lines. Amani has also made a short film called SAVE ME, which has been commissioned by Enfield Council and London’s Violence Reduction Unit to be used as a training tool.

With the conversations in Parliament and the powerful themes of the film, Femi hopes that TRAPPING can make an impact. When Amani raises the idea to show both his film alongside Femi’s in schools, they’re both in agreement. “I’m all for collaboration. You can take the film into schools, I’ll make it available to you Amani and you can do whatever you need to do with it,” he says.

“It’s important for everyone to know that these are all our children,” Amani responds. “Even if it doesn’t necessarily come into your household, these are going to be the children that are around your children. Ultimately, we all have to come together to make this work. Otherwise, it’s going to be another 10 years of us talking about the same things.”

Watch TRAPPING at The Drop.

Follow Isaac on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.