The Sikh Polar Explorer at the end of the world

- Text by Phil Young

- Photography by Courtesy of Preet Chandi

“I remember that feeling of being like I didn’t fit in,” says Preet Chandri. “And it’s hard, because you don’t even want to say it. I didn’t know there were no polar bears on Antarctica because I don’t want people to think I’m stupid. It felt like going to a dinner and not knowing which knife and fork you’re supposed to use.”

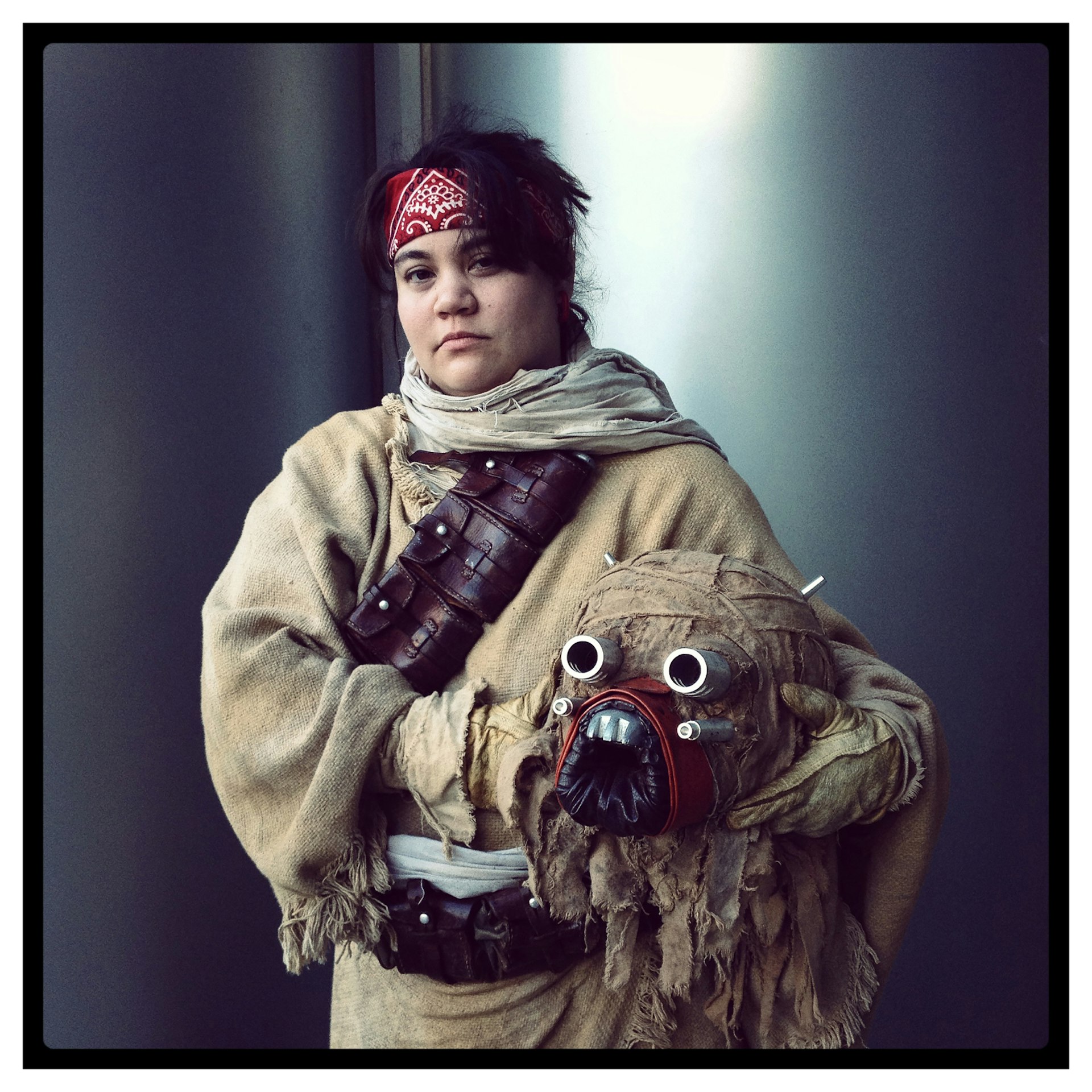

In my head the term ‘Polar explorer’ brings up an image of Shackleton or Scott, Hillary or Amundsen. Windswept and interesting, gnarled and rugged, a fascinating beard that holds court around a flickering oil lamp, probably with a pipe. Preet Chandi MBE however, is tall, slim, melanated and good at tennis. Her hair looks as though it’s no stranger to product and she sometimes wears lipstick.

She smiles a lot and is a peculiar type of earnest that’s hard to pin down. A Sikh woman that boldly defies the perception of what European adventurers are supposed to look or act like.

I initially became aware of her when I stumbled across a picture on Instagram of Preet dragging a car tire up a hill, then met in person at her inaugural Antarctic trip champagne reception. Held at the Shard in London on behalf of her sponsors, it was an interesting experience. I felt out of place, easily the most underdressed in the room and one of perhaps ten other people not from big business or the army.

An awkward chat with a fearsome female brigadier who looked like she had secreted a bayonet about her person gave me a sense of the world Preet inhabited. In getting to know her, I increasingly get the feeling that this isn’t the place she is most comfortable, even though she has had a presence in the military since 2008. She served as a physio at the rank of captain and has been on operations in South Sudan, Nepal and Kenya.

“I’m now on my career break from the Army, it’s nice because it just gives me some time,” Preet reflects. “One of the things I struggled with so much before was that it was all just so busy. Now I have a bit more capacity, I realise all the things in my life I didn’t have time to do. Hopefully now I can try and make some money back and, you know, live. There are so many things I want to do.”

Preet’s a talker. The words not so much spilling, but cascading out. It’s a river of consciousness, with rapids of excitement and eddies of self-questioning. It’s rather overwhelming when conducting an interview and I’m forced to abandon my prepared line of questioning from the get-go. I like this approach, and I’m intrigued by Preet as a person.

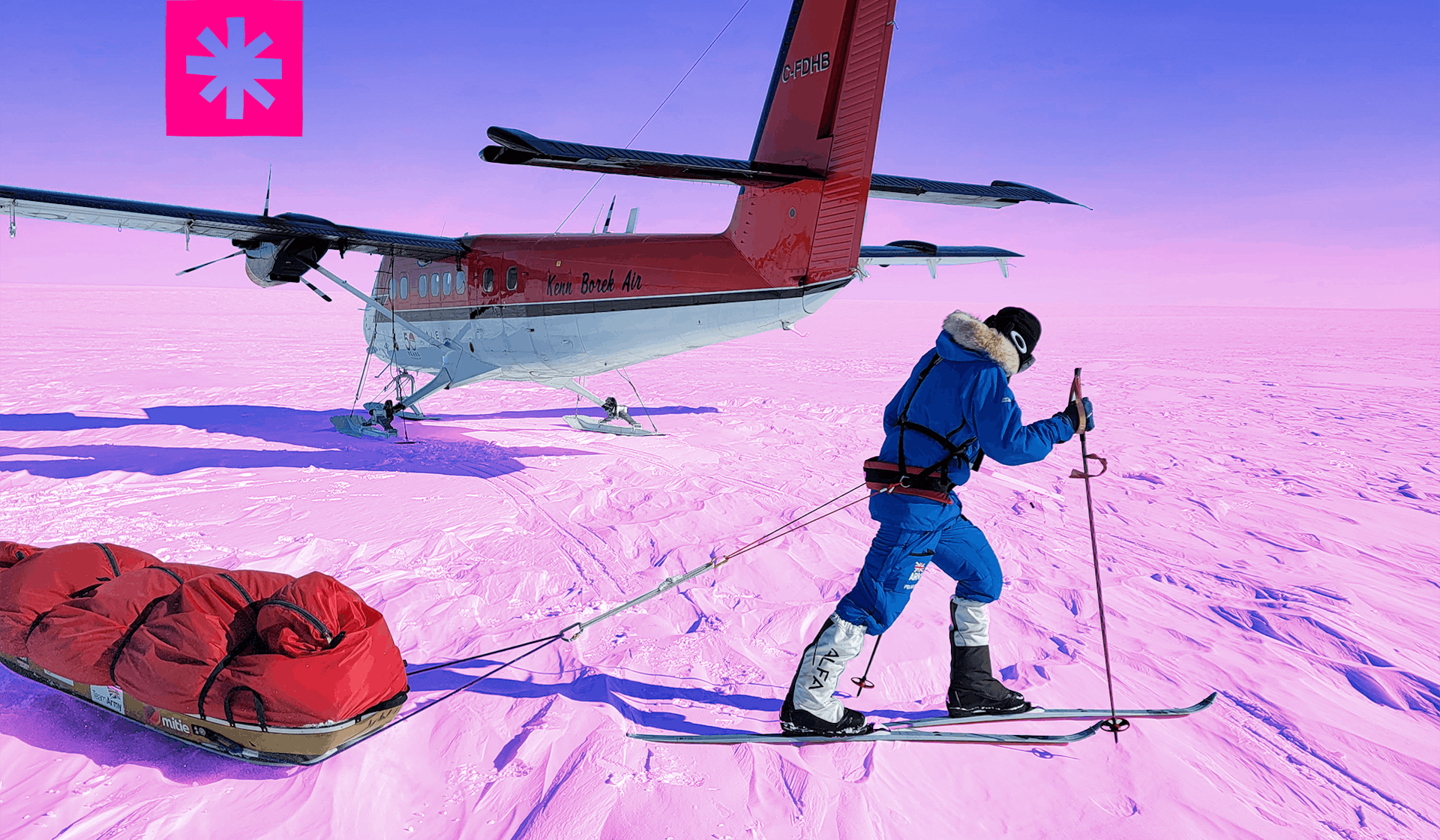

At the time of writing, she has been to the Antarctic three times, each visit raising the bar on personal and world records. She is the first Woman of Colour to ski solo unsupported to the South Pole, holds the claim of longest journey ever skied solo unsupported one way across the Antarctic (1,485km in 70 days and 16 hours) and it the fastest ever woman to ski solo unsupported to the South Pole (1,130km in 31 days, 13 hours and 19 minutes) – the last two records both claimed in the same year (2023). She was named the ’23 Explorer of the Year by the Scientific Exploration Society.

“I needed to go for a wee, I looked for the Shewee, which is always in the same zip and it wasn’t there. I was like ‘really?’ So that’s the difference between me standing up and going for a wee and having to squat and unzip, like undo all my layers. It was hard work and it was taking me so long to even get into the squatting position. My neck was so sore I had to lift my head with a ski pole. I don’t cry easily but I balled my eyes out.”

For about five months of the year the sun never manages to rise above the horizon. In the summer months, expect 24 hours of constant sunlight and an average temperature of around -27°C at the pole. The pole itself is high, sitting on top of an ice plateau at 2800m above sea level, yet because of centripetal force – an effect of the planet’s spin – it throws much of the atmosphere toward the equator and thus makes it feel even higher.

With the exception of a couple of small, hardy plants, some penguins and seals around the coastal regions, and the odd creepy crawly on the nearby islands – it is devoid of life. Nature in all its tenacious ability to fill a niche has thoroughly failed; it’s shut the door in defeat and hung up a sign saying ‘closed for business’. It is bleak, hostile and inhospitable in the truest sense of the word.

“It was cold and windy, and the last few days were like a nightmare that I just couldn’t get out of,” she says. “Everything that could go wrong seemed to. I’m rationing my food because I’m doing such long days and I was starving. I was so hungry, not even able to have the tiny piece of chocolate I wanted because I needed it for the next day, it was unbelievably hard.”

Notwithstanding the occasional glimpse of blue sky, your clothes or your equipment, colour simply doesn’t exist in the Antarctic. Assuming it’s not a total white out, it’s a white-leaning grey-scale as far as the eye can see in every possible direction, all of which is north. No life, no colour and limited topography for hundreds of miles. Other than the physical feeling of pain, the only sensory input is often just the sound of the wind as it hurtles across a barren landscape colliding with million-year-old ice crystals of intense purity across a single human, which, by all rights shouldn’t be there. The monochromatic loneliness of the desolate environment can be debilitating, a self-imposed solitary confinement on the edge of the world, the stuff of post-apocalyptic horror novels and real life tragedy.

“I was like, I don’t know if I can keep going but I didn’t have a choice as I saw it. I wanted to curl up in a ball, at one time I 100% did.”

To classify as a ‘ski solo unsupported’ attempt you cannot accept any external resupply of food or equipment. This means you have to take everything with you, in this instance ‘take’ means ‘pull’ and the pull is a sled called a pulk which holds all the hardware (tent, food, stoves, spares, radio, etc) necessary for your survival. Subject to the type of trip, the contents of Preet’s pulk is about 70-90 kilos. It’s the equivalent of pulling a newborn elephant, a fully grown male leopard or two ceramic toilets – every day, over a frozen hellish wasteland for two and a half months, whilst avoiding crevasses and generally trying your best not to die.

“It wasn’t easy to do, you know, I’m not like a skier, it was bloody hard. I think part of it is not just to prove to myself, but prove to others and say, ‘Look, I’m really working to do this.’”

Humans are physiologically pretty bad at dealing with extreme cold. Our knack, it seems, is learning how to protect ourselves when faced with challenges. It’s often the psychological impact of such journeys that prove the hardest to adapt to. The level of fear is extraordinary when out in such hostile environments, as is the intense loneliness experienced from long periods of isolation. Disturbed sleep, impaired cognitive ability, hunger, exhaustion all create unhealthy levels of anxiety that play dangerous games with the mind. “I’ve got horrible thoughts going into my head. And at the same time, I was so empty, I was just broken,” she says.

In our daily lives, we are bombarded with information. When deprived of this for prolonged periods, almost everyone will experience hallucinations as the brain’s nerve pathways attempt to make sense of the lack of sensory stimulation, creating a fantasy world to fill the void. Depression can hit, especially at the dreaded half-way mark when individuals, already weak and slightly traumatised, realise that they have to do it all over again. This ‘third-quarter phenomenon’ can be make or break but as Preet says: “Antarctica isn’t just a place on the map; it’s a test of human endurance and resilience. My expeditions there taught me the true meaning of perseverance.”

If, after understanding all of this, you decide that the Antarctic sounds like your kind of place, the best time to attempt a challenge is during the southern hemisphere summer between November and January. 24-hour daylight and comparatively manageable temperatures provide the best opportunity for success, both in terms of realising your attempt and in sustaining your life. There are a number of possible routes to the pole but Preet chose the most ‘popular,’ although not the shortest, from The Hercules Inlet, which could be described as being on the west of the land mass – although, technically when you are at the pole there is no west.

From sea level you encounter a steadily hard climb through a highly crevassed route until you eventually reach the polar plateau. Once on the ice cap it’s a continuous slog of a rise, generally with a headwind, over large windblown sastrugi (snow and ice structures created by wind erosion) until you reach the pole. As well as managing energy, injury, heat regulation, illness, mental health and navigation, you are given a strict cut-off point for any attempt; the last flight out doesn’t wait for late comers. There are eight times as many people who climb Everest in a year than have ever made a successful solo unsupported attempt to the South Pole. It is in short, one of the toughest long-distance human powered challenges a human is physically and mentally capable of doing.

“It’s an amazing place to be,” she says. “It is. It’s a huge white desert on a sunny day, so when the sun is out you can see for miles and miles ahead, but it all looks the same – you have no idea if you are going the right direction. It’s hard mentally because you don’t have any landmarks that you can reference, the only way you can tell which way to go is because of your compass and sometimes the wind direction.” Her eyes seem to defocus, I feel she may have been transported back to a moment on one of her trips. It’s a rare break from her earnest storytelling where she gives limited time to reflection.

The way Preet presents herself is deceiving, she’s served all over the world and has a legitimate list of hikes ticked off the adventurer’s handbook. She’s knocked out marathons and ultras, including the infamous Marathon des Sables, often touted as one of the toughest foot races on earth. The army has undoubtedly given her a sense of determination, resilience and order in her preparation and methodology, as well as opportunities to experience much of the world.

However, I sense that this is a non-typical relationship, multifaceted and complex. There are currently around 75,000 active personnel in the British army, of whom about 11-12% are females and in total roughly 130 identify as Sikh, just 0.17% of the army. We don’t need to have served to get an idea of what the experience of a Sikh woman in the army might look like, so when I touch on it she is guarded.

On her first trip she took unpaid leave, having to find sponsors and self-fund the entire attempt, returning with a ton of debt. Not necessarily the picture you get when you go online to read the features and see the news clips. Upon getting back she was sent on a season-long PR push into schools, driving up and down the motorway telling her story and, we assume, giving a soft touch army sell. “It was an intense time. I came back from the best trip and then I was literally doing four months of school talks back to back before going straight back to work on the Monday,” she sighs.

Preet is an obvious role model for young people, although the cynics out there may use the word ‘paraded’ to describe a school tour, and could be forgiven for thinking a deal has gone down somewhere along the line. However well-intentioned and honourable the army’s use of her, she is definitely ticking a few boxes for their failing diversity figures. Preet seems comfortable with this, however.

“At the end it’s just so raw, you know what I mean? Just so incredibly raw. Every step I took in Antarctica was a reminder of how far I’ve come and how much farther I can go. My journey is a testament to the power of self-belief and determination.”

There is an irony to going to the edge of the earth by yourself and not finding escape. For climbers, runners, rowers, swimmers, anyone who feels the visceral urge to explore the tolerance of the human mind and body, there comes a time when even the most psychologically defended must face the inevitable and confront their very being.

“It’s a mental prison,” she says. “Your darkest, deepest thoughts come to you and there’s no escaping them. I struggled mentally just to get away from my own thoughts, my demons. All the frustration and anger towards people, who I felt went out of their way to make things a little bit harder for me, or not let me go and push my boundaries. That’s tough. It wasn’t fuelling me. I wasn’t able to use the frustration or anger to help me do the task. It wasn’t helping me, it was dragging, like pulling extra weight.”

The ‘people’ she refers to could be described as ‘the establishment,’ although she’s quick to point out that there were numerous individuals in the outdoor industry that have supported her and made her trips possible. But that’s the elephant in the room, the Brown girl who didn’t know there were no polar bears in the South Pole and then turns up and snatches records from the hands of white men. It’s bound to grate in the wooden-panelled halls of some long-standing gentlemen’s clubs. Claims that she’s ‘not a real explorer’ or that she doesn’t deserve the accolades she has received feel at best bitter, and at worst misogynistic and potentially racist.

“As a Woman of Colour, I’ve faced skepticism and prejudice in the outdoor community. But I refuse to let anyone dictate what I can or cannot achieve. Exploring Antarctica isn’t just about conquering nature; it’s about understanding our place in the world and preserving its beauty for future generations.”

When I speak to people like Preet I always wonder, “Why?” Why go to such far reaches? What’s the pot of gold that you are hoping to find?

“You know what?” she says to finish the interview. “For me, it’s that we are just as capable. I have been in so many spaces where I felt I did not belong, and you know what? We do belong. I want to say to people that for me it’s adventure, but for you it could be literally anything. It could be education or sports, whatever it is for you, do it, whatever you feel like. You do belong.”

Follow Preet Chandi on Instagram.

The Outsiders Project is dedicated to diversifying the outdoors. Follow us on Instagram, read more stories or find out more about partnering with us here.