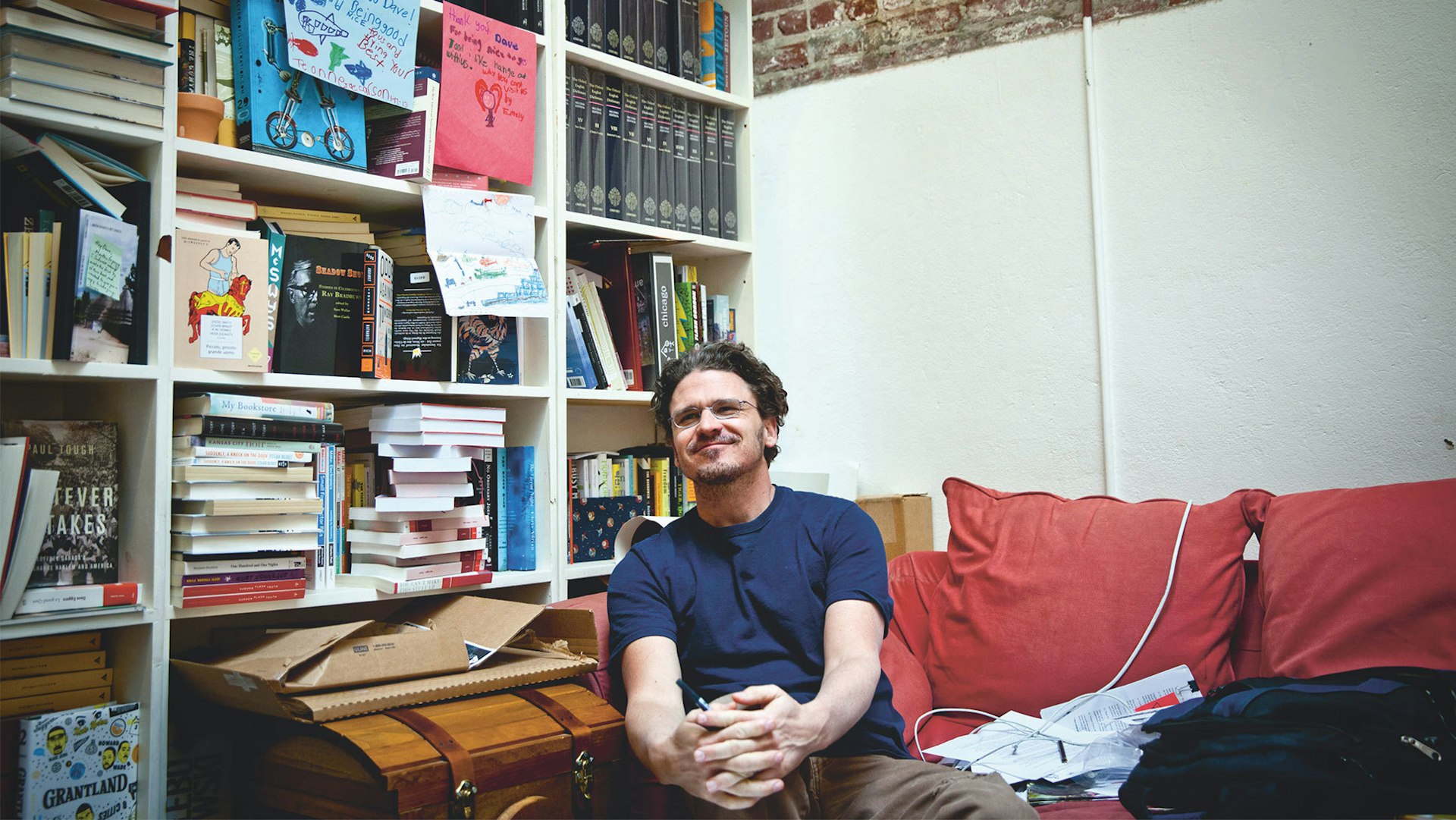

Dave Eggers

- Text by D’Arcy Doran

- Photography by Ariel Zambelich

“We have more time than you think,” Dave Eggers says as he settles into the red sofa that serves as his desk in the corner of McSweeney’s office in San Francisco’s Mission District – also home to The Believer magazine and a growing array of other publications. All at once, his words are an apology, an assurance and, just maybe, he is letting us in on a secret. Stretching and slowing time is a power Eggers, now forty-three, possesses both on the page and in real life. Moments earlier he was working out details for an album of songs written by Beck and performed by several bands to raise money for 826 Valencia, his pirate store-fronted tutoring centre across the street and its seven sister centres. In just over an hour, he’ll huddle with teens in McSweeney’s basement for their weekly class to compile his offbeat annual, the Best American Nonrequired Reading anthology. Then he will disappear into his garage for the rest of the week to finish his next non-fiction book The Visitants, which collects more than a decade of travels around the world. As he talks about Visitants, the office walls seem to fade and it’s easy to picture Eggers in a stranger’s car barrelling across the desert at “900 mph”.

He was in Jeddah on his last day in Saudi Arabia researching his novel A Hologram For A King – a tale about a struggling American businessman whose last-ditch attempt to stave off foreclosure leads him to a rising Saudi city – when Eggers realised his flight home was actually leaving from Riyadh, more than 1,000 kilometres away. He flagged down a stranger, not a cabby, or even a professional driver, and hired him to speed across the desert. Thirty minutes into the seven-hour drive, as all traces of human settlement vanished, the driver phoned a friend, chatted in Arabic, then glanced at Eggers and said into the phone in English: “Yeah, American. Boom-boom.”

Eggers picks up the story:

I don’t know what that means. It doesn’t sound good, you know? We have complicated relations with some young Saudi men. Although everyone I met when I was in Saudi Arabia I had a great time with. I met a lot of friends. But this guy? You start letting your brain go and you start getting a little paranoid. Could this be bad? I’ve always assumed the best of anyone I’ve met and I’ve always had faith in everybody because I want them to have faith in me. I’ve trusted them because I want them to trust me.

But this was right after a friend of mine, Shane Bauer, had been arrested and imprisoned in Iran. He was in for almost a year. He was a translator who did a lot of work here, he did Arabic translation for us for Zeitoun and for the book we did in Sudan. So here I was thinking, ‘Well nothing ever bad has ever happened to me so I have to believe this is going to be fine.’ But in the back of my mind I actually know a guy in an Iranian prison, who was picked up for hiking over the border. Your mind starts running.

The episode opens The Visitants, his first book written in the first person since his debut. It tells the stories behind the books, including journeys to Saudi Arabia and China for Hologram, trips to Syria for Zeitoun – the true story of Abdulrahman Zeitoun, a Syrian-American who remains in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina, distributing supplies from a canoe but then disappears – and Eggers’ venture into South Sudan for What is the What and his Voice of Witness series, which highlights social injustices around the world.

The rest of the book follows the same arc, which is going in as a blank and completely open mind and then letting yourself be informed, or made concerned, or even paranoid, by things that you hear outside. And then realising the dangers of that second-hand knowledge and making assumptions, and then finding common humanity.

At a certain point, I pulled out photos of my family and I was like, ‘Hey, you have kids too?’ You’re trying to find some common connection. By the end of it you end up being as friendly as you can be with a guy you’ve barely met and you’re paying to drive you.

One of the impetuses [for Visitants] is just hearing that travel rates are down among younger people. Fewer passports are being issued and fewer people in their twenties leave their state and have their driver’s license. They attribute all this to online time and people feeling like they’ve seen things because they have access to it all. There’s a little bit of me that’s wanting to say, ‘Really, you don’t know anything until you’ve been there, or until you’ve met somebody.’ You don’t know the first thing about a young Saudi unless you’ve met a young Saudi. You can’t make an assumption about the lives of Saudi women unless you’ve met them and really listened and really gone somewhere. It’s the value of real-world, tangible experiences, person-to-person contact.

Your first book was extremely close to home, but ever since your second, You Shall Know Our Velocity! – about two friends travelling the world in one week to give away $80,000, a sum they feel was undeservedly inherited – you shot off, telling stories that span continents. Is something pulling you out into the world?

A lot of writers will spend their careers plumbing their lives in different ways or sublimating their experience through fiction. But if you start with a memoir, you’ve sort of blown that. From the beginning, I couldn’t find anything left to write about. And you also get a taste of that and it’s enough.

But ultimately my training was in journalism and that was my background for a long time. So I just developed an interest. I got hooked on the process of feeling like I could communicate a good story to an audience to maybe have an impact.

I’m always trying to educate the person I was too. I was just talking to a friend who grew up in the Bay Area and was saying, ‘You don’t understand the bubble we’re in sometimes.’ A lot of people like me in Illinois, or Wisconsin, we’re well-meaning people, but you would be surprised how ‘in the middle of nowhere’ we are in terms of our awareness. I didn’t have a passport until I was twenty-six. There’s a lot of people like us and you’ve got to be forgiving of people like that. They have good hearts.

Especially with What is the What and Zeitoun, I’m speaking to those people I grew up with. We’re all incredibly nice people who might not be aware of what happened in New Orleans after Katrina, or might not be aware of human rights crises that Voice of Witness tries to illuminate. I do try to remember who I was and where I came from. There’s still many other millions of people in a country as big as the US that want to learn about these things and if you can start from a place of, ‘Hey, I was there too. I couldn’t have placed Sudan on a map when I was twenty-five, but I’m going to walk you through it.’

The Revolution

When Eggers, with his little brother in tow, and a few high school friends, left the suburbs of Chicago for San Francisco in the early nineties, they set out to start a revolution. Their call to arms would be an indie magazine. The plan was that Might magazine would “force, at least urge, millions to live more exceptional lives, to do extraordinary things, to travel the world, to help people and start things and end things and build things”, as he explained in a manic moment in his memoir. But they soon learned that simply writing about a problem didn’t solve it. Frustration fuelled cynicism, he says, which increasingly crept in over Might’s three-and-a-half-year run. After the magazine’s demise, Eggers moved to New York to become an editor at Esquire. But the glossy magazine world disillusioned him. He left to write his first book and on his kitchen table in an act of procrastination, created McSweeney’s Quarterly Concern, initially a home for stories rejected by glossies.

He returned to San Francisco as a best-selling author to set up the McSweeney’s office. Inspired by friends who, like his mother, were teachers, he decided to put a classroom at the centre of the office at 826 Valencia. In contrast to Might, Eggers says, 826 had immediate impact from the very first student. He had stumbled on a model for sustainable, effective, community-level change. The centre’s success inspired McSweeney’s collaborators Nick Hornby and Roddy Doyle to set up transatlantic cousins, the Ministry of Stories in London and Fighting Words in Dublin.

With each book, Eggers finds a new micro project. What is the What – which tells the real story of Valentino Achak Deng, one of Sudan’s lost boys, who fled civil war by crossing the desert on foot, eventually finding his way to America – inspired a foundation that built and operates a school in Deng’s home village. His travels in South Sudan for the book also led to Voice of Witness, a nonprofit series that aims to empower victims of human rights abuses by sharing their personal narratives. Zeitoun spawned the Zeitoun Foundation, which funds reconstruction projects in New Orleans and promotes understanding between Muslims and non-Muslims. Hologram, a book about outsourcing the American dream, inspired his latest initiative, the Mid-Market Makers’ Mart. It’s a proposal to set up a market/workshop space in San Francisco’s long depressed mid-Market neighbourhood where artisans can make and sell goods ranging from surfboards to stuffed animals. “I would like to bring my kids to a place where you can see things being made and in a couple of hours you might be able to see fifty different makers and buy something original,” he says.

How do these projects come about? Is it that after writing the book you feel there’s something left to address?

It always comes out at about the same time and it’s something I’m trying to cure myself of. I always thought there had to be some real-world application. So when I wrote about Valentino’s life [in What is the What], we thought of a school in his hometown and then the Valentino Achak Deng Foundation. We built this school and all of these buildings happened from Valentino’s story. Now they’ve graduated their first class. Then it was the same thing with the Zeitoun Foundation. Although it was a little different – all those funds went to existing nonprofits so we didn’t have to start anything from scratch. But again it’s trying to make something tangibly impactful out of a story. But I really don’t have all the time and energy that I used to. It’s a lot of work because these continue to exist. They need my help every so often. These things start adding up. So to do any of them well I have to stop doing new things. I’ve come to grips with that recently.

Is it that the idea builds inside as you’re writing, because writing alone isn’t enough?

There’s a lot of different reasons. But one is that writing is incredibly solitary and sedentary. I sit on a couch just like this that’s in my garage. It’s filthy. I sit there eight hours a day to get any kind of work done. It took me a really long time to get used to all that time alone. I’ve always been part of a group like a magazine or a newspaper or whatever. One, you feel incredibly guilty about your parents having actually worked for a living and you get to sit on a couch in your garage and think of stuff. That doesn’t seem like real work to me. So you try to alleviate a little bit of that guilt by trying to make something impactful in the actual world. That’s the truth just as a lapsed Catholic.

Then there’s the idea, ‘Wouldn’t it be fun to get a group of people together and let’s open a centre and let’s have a publishing company?’ because it addresses your social needs. Then, ‘Boy, it’s not that hard to put a book together and I’ve got a buddy, he just sent me his book that he can’t get published. How hard would it be to publish that book?’ You publish one magazine and it’s not so hard, so you think, ‘What would it cost to put out a different one?’ It starts adding up and before you know it, you have a habit.

And you don’t want people to tell you, ‘No.’ So if I want to publish a book, I would like to publish it. I don’t want somebody to tell me that I can’t. So you create a situation where you continue to publish your own work, or the work of people that you like. It’s worth it to not be told, ‘No.’

To read the full interview, grab yourself a copy of HUCK #038.