The skater who became a shaman

- Text by Anthony Pappalardo

- Photography by Jason Henry

Greg Carroll strolls through a nature reserve in Sacramento, California. He clutches a handful of feathers, used to cleanse negative energy, and a handheld drum, whose beat symbolises the heartbeat of mother nature.

It’s a bucolic scene, the kind of moment that populates Instagram feeds tagged with #inspirational. But for Greg, life wasn’t always so serene.

Growing up in Daly City, near San Francisco, his mother had a tempestuous relationship with a Vietnam War veteran who, he explains, was exposed to Agent Orange and struggled with alcoholism.

At first he seemed like a dream father-figure – taking the boys out for all sorts of activities – but over time the atmosphere grew toxic. The boyfriend would idle away hours drinking gallons of cheap vodka, inflicting mental and physical abuse across the household.

“One day I heard [my mom] screaming,” Greg says. “It sounded like he was throwing her around the room. He said that if I called the cops, he’d kill her. I called 911 anyway but by the time they showed up, he was passed out. Once again, they didn’t do anything.”

In 1988, the couple moved out altogether, leaving 17-year-old Greg and his 13-year-old brother Mike to fend for themselves. Greg’s income from odd jobs covered up the lack of parental supervision. But no matter how hard things got, the Carroll brothers always had skating.

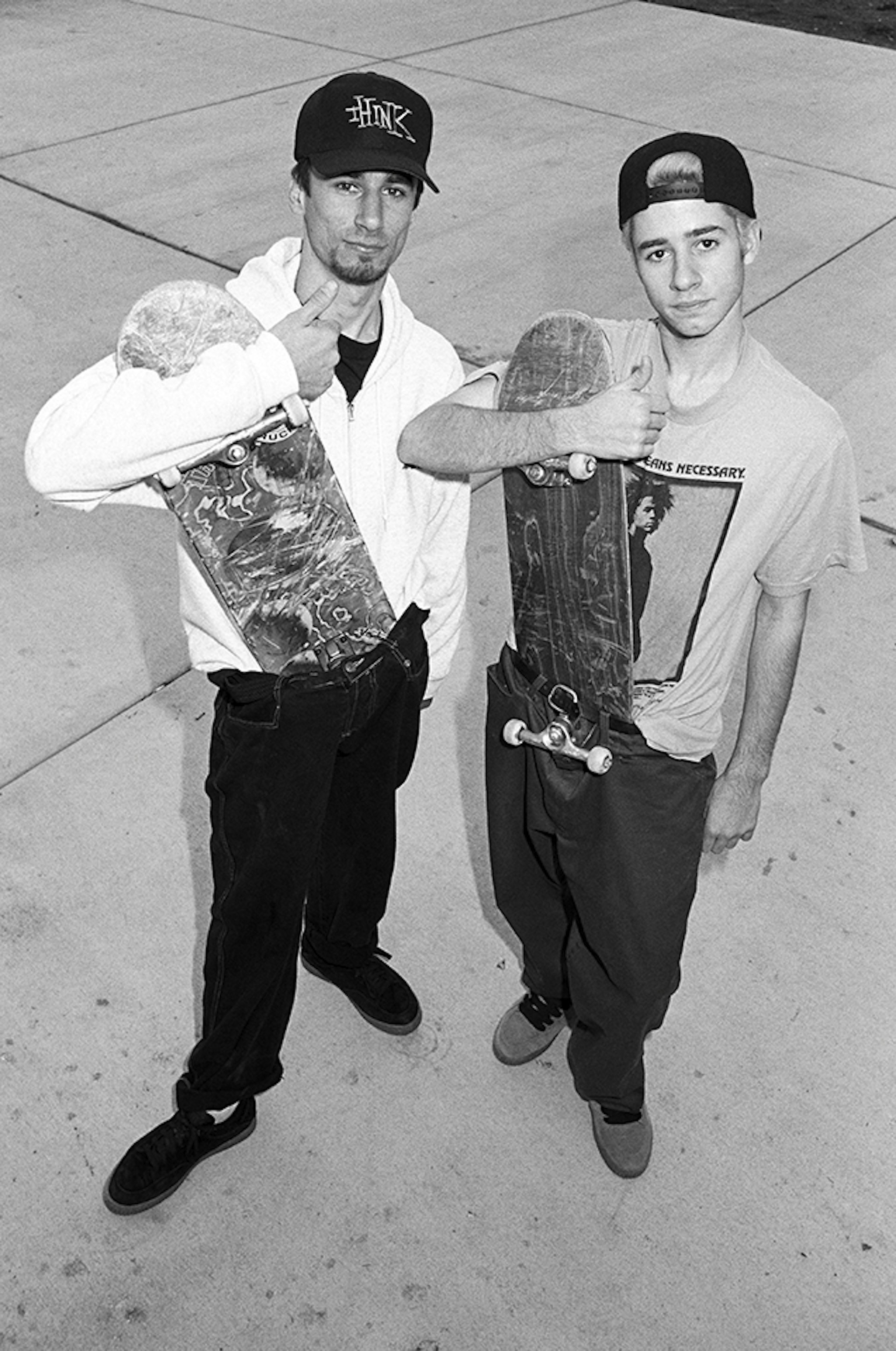

Greg Carroll and younger brother Mike, San Francisco, 1992. Photo by Bryce Kanights.

Their home even became a crash pad for future legends like Danny Way, Sean Sheffey and Henry Sanchez. “Other kids could go over to their buddy’s and raid the fridge or whatever,” Greg says.

“Our house wasn’t like that. We didn’t have anybody cooking or doing laundry for us. ‘Dude, that’s my food. Mom didn’t buy that for me!’ And we never had parties. I remember being at one where these dudes threw somebody out the front window. Fuck that! Not at my place.”

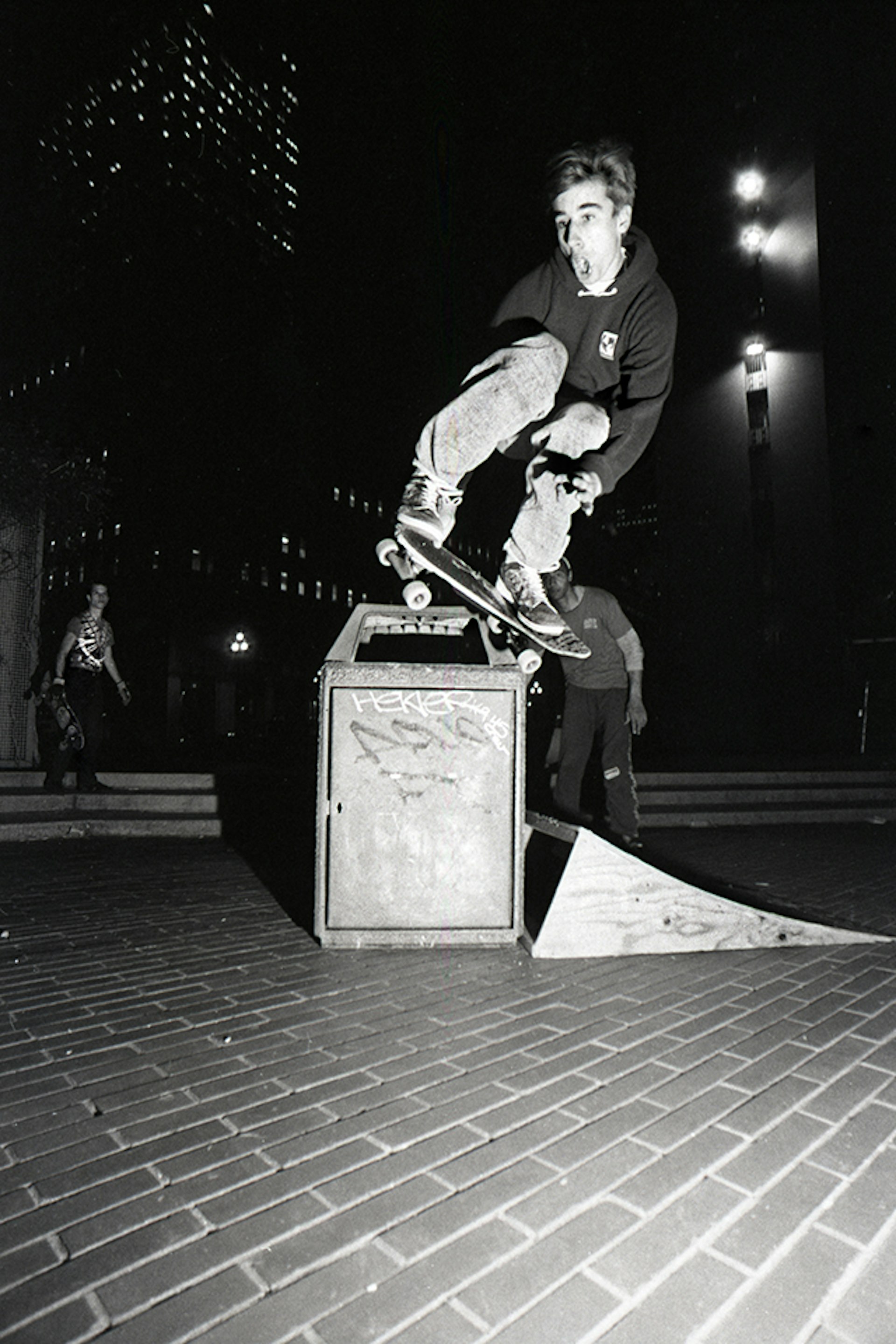

Instead the streets of San Francisco became the brothers’ playground. Justin Herman Plaza, a spot near the waterfront known as Embarcadero, turned into ground zero for street skating.

Its combination of location, terrain and general lawlessness attracted a new wave of skaters intent on pushing each other towards technical innovation.

Skate media may have been slow to catch on, but a fertile community sprung up around the plaza’s rickety surfaces.

By 1989, Mike Carroll turned pro and Greg was asked to become team manager for Venture Trucks. “At first I just laughed,” he says. “I was like, ‘Those trucks suck. I’m never going to ride those things!’ But then they said I could redesign them however I wanted.”

A sense of opportunity dawned on him. Board shapes, shoes and wheels were already being adapted to new tricks and obstacles – and Greg knew it was time for the truck industry to catch up.

Greg Carroll at San Francisco’s Embarcadero – ground zero for street skating – circa 1987. Photo by Gus Duarte.

“We were skating on ledges all the time, with everybody’s bolts spinning off and grinding down, so I thought, ‘If we could just drill the trucks back and do the hole pattern smaller, we wouldn’t have this issue.’

“I knew it was going to change skateboarding, but what we didn’t factor in was how it would change the actual geometry [of decks]. We quickly got angry calls from manufacturers asking what the fuck we were doing.”

What they were doing was sending a message to skaters looking for the cutting edge: ‘If a board is drilled with the old pattern only, it’s wack.’

One by one, manufacturers began phasing out the old style. Venture, meanwhile, morphed from a little-respected brand to the top-selling trucks company in the world.

But back in 1989, 18-year-old Greg had another enticing opportunity. Fausto Vitello, the Argentinian-born creator of Thrasher magazine and founder of Street Corner Distribution, invited him to start his own brand of board.

The launch of Think Skateboards saw Greg eschewing professional skaters – opting instead for a grassroots campaign that focused on young talent in big numbers – and developing an aesthetic inspired by the nascent rave culture taking over San Francisco’s warehouses.

But despite its success, Greg began to feel unsure of himself. His identity felt scattershot: there was the skater, the businessman, the disciplinarian, the sensitive mentor.

Ecstasy helped him balance things out, but Greg got so into the drug that he started dealing on the side, triggering a dark time in his life.

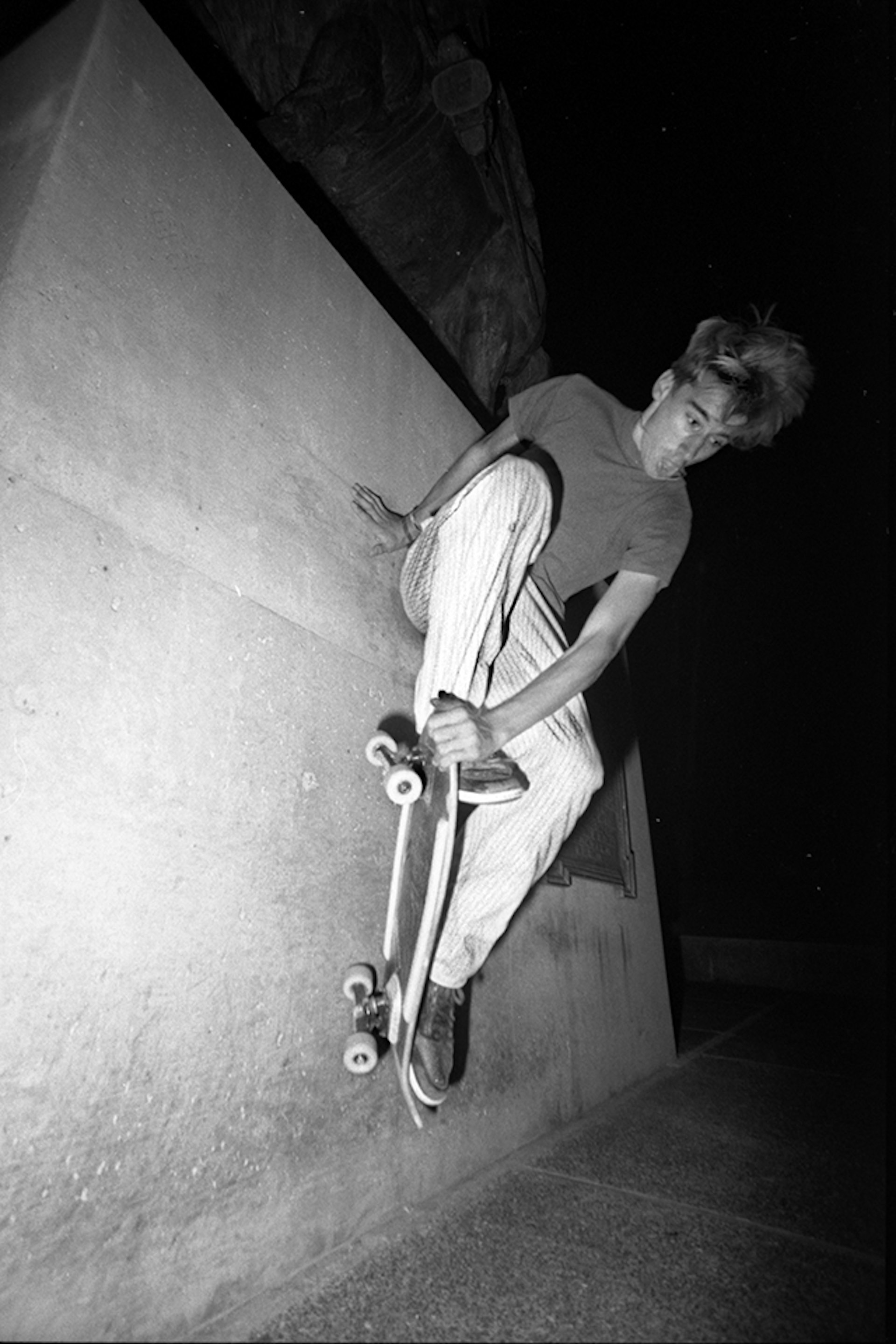

Photo by Gus Duarte.

“I was doing it so much that I didn’t even… How can I put this into words, man? I didn’t care. I had around 10 years of strong partying with ecstasy: in the clubs for a while, then hitting Vegas with my boys once a month and just going nuts. One New Year’s Day I walked out of a club by myself just fucking depressed. And that was it. That was my bottom. I never looked back.”

Exhausted and sick of travelling for work, Greg turned his attention to the back-end of his various businesses. He’d always felt that the industry lacked transparency and the more he dug around, the more he found widespread disparity between salaries and profit margins.

“I love skateboarding but the industry sucks,” he says vehemently. Hungry for a change, Greg came up with a new distribution model whereby fledgling brands wouldn’t need a warehouse or a sales team, only creative input and a marketing vision.

In 2006, he launched a new business – Empire – that would act as a middleman, negotiating deals with distributors directly.

At the time, streetwear was on the rise and skate companies had failed to take the market seriously. Greg channelled his frustration with skewered profit margins into a bold idea: he wanted to ramp up the wholesale price of T-shirts to a whopping $18.

“All the shops were like, ‘What the fuck? How am I going to sell that?’ I told them [premium apparel] was going to be like crack… And that’s exactly what happened. It blew up.”

Greg Carroll, 2017. Photo by Jason Henry.

But in 2008, the economy faltered. Given that Empire didn’t actually own any brands – only managing deals – income dried up as sales slowed. Slipping into survival mode wiped Greg out.

At the height of his sleep-deprived mania, his girlfriend and future wife, Ariel, insisted that his energy sucked. It felt like a wake-up call.

“I called up one of my business partners and said, ‘You know what? I’m done.’ We shut Empire down within a week. Doors closed, defaulted on all our business loans, our lease on the building – everything. The next day I had a full-blown panic attack. I thought, ‘My daughter is going to be born in February. It’s 31 October. I’ve got to figure this out.’”

One day, in 2010, Greg wandered out to Lands End – a windswept hiking trail along the Golden Gate shoreline – and reflected on his path.

Nearing 40, he realised this was the first time in his adult life that his name hadn’t been attached to a brand.

But after searching for clues about what to do next, the only thing that kept coming back to him was, “Be yourself.”

And he had no idea what that meant. “You love helping people,” Ariel told him. “Why don’t you just be that?” She was right: it had been the only constant across those identities. Fausto had even called Greg “the Ghandi of skateboarding” for the way others listened to him.

“I counselled people my entire career,” he says. “You get 10 dudes in a van for a road trip, you’re counselling them. Even before that my mom would trip out like, ‘What are you, the school counsellor?’ Because all these kids would call the house. For some reason, I’ve always had the ability to build rapport with people and help them.”

After an accident in 1998, a friend suggested Greg see a healer for his back pain only to be told, “I don’t buy into that hippy shit – fuck that!” But now the idea of spiritual energy had grown on him.

At a retreat in Sacramento, California, Greg Carroll burns tobacco to cleanse some feathers he uses to remove negative energy. Photo by Jason Henry.

“I was always empathic… I knew my mom and dad were getting a divorce, even though there were no signs of them fighting. My dad sat us down one day when I was in third grade and said, ‘I don’t love your mom anymore, I’m leaving.’ I went into shock. It felt like my consciousness just shut down after that.”

For him, practising Korean energy work and studying with Native American elders, as well as shamans versed in ayahuasca ceremonies, became a way of resurrecting that consciousness.

Greg is self-aware enough to know how jarring all this sounds – “People who know me might be like, ‘What? This dude’s tripping!” – but he’s genial and considered about it, never preachy.

Just as his own life coach and shamanic practice began to take off, however, life threw up some challenges. He discovered that his mother, whom he hadn’t seen in 23 years, had lost her husband – the Vietnam vet – to suicide.

When Greg tried to reconcile their relationship, he found her living in squalor and suffering from dementia.

Greg fixed up the house, moved his family in and tried to get his mother the care she needed – but the relationship remained fraught, demanding so much that Greg’s work suffered. Things got so bad that the family lived on welfare and Ariel became suicidal.

Then, one afternoon in 2015, Greg took his young son for a skate and blew out both his knees in a freak accident.

“At that point I called up a friend and was like, ‘I can’t do this alone anymore, dude. This is too hard.’”

The friend started a GoFundMe campaign online, paying tribute to Greg’s character and inspiring the skate community to donate nearly $29,000. Despite the mass support, a handful of haters questioned why Mike – long established as a skate icon – didn’t step in.

But Greg insists that his problems are not his brother’s responsibility. Besides, seeing that people genuinely cared, Greg says, helped pull his wife out of depression.

Slowly but surely, the family turned a corner. Greg managed to get back on his feet and return to healing, restoring balance in other people’s lives. Often it’s tech entrepreneurs from Silicon Valley – a new generation of industry disruptors – seeking guidance from someone who understands where they’re coming from.

Photo by Jason Henry.

“They’re stressed the fuck out because they have too much property, too many bills; they’re on this roller-coaster with their job and yet there’s a thousand people out there, ready to take their position. That’s not living.”

For Greg, change starts with a simple walk outdoors. It’s the perfect place to reflect, reevaluate and navigate towards a healthier future.

People are so detached from each other and from nature, the 45-year-old explains, that they can’t believe how simple the healing process can be.

“I’ve seen full-blown miracles happen where people are ready to die one day, then wake up the next morning and their life’s completely different.

“And all it takes is a conscious decision to say, ‘You know what? I’m not doing this anymore. This doesn’t work for me. I need help.’ And if people can’t handle the magnitude of what you’re dealing with, then find someone who can.”

This article appears in Huck 59 – The Game Changer Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Find out more about Greg’s shamanic practice or check out Seb Carayol’s The FTC Book, which documents the San Francisco skateboard scene.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.