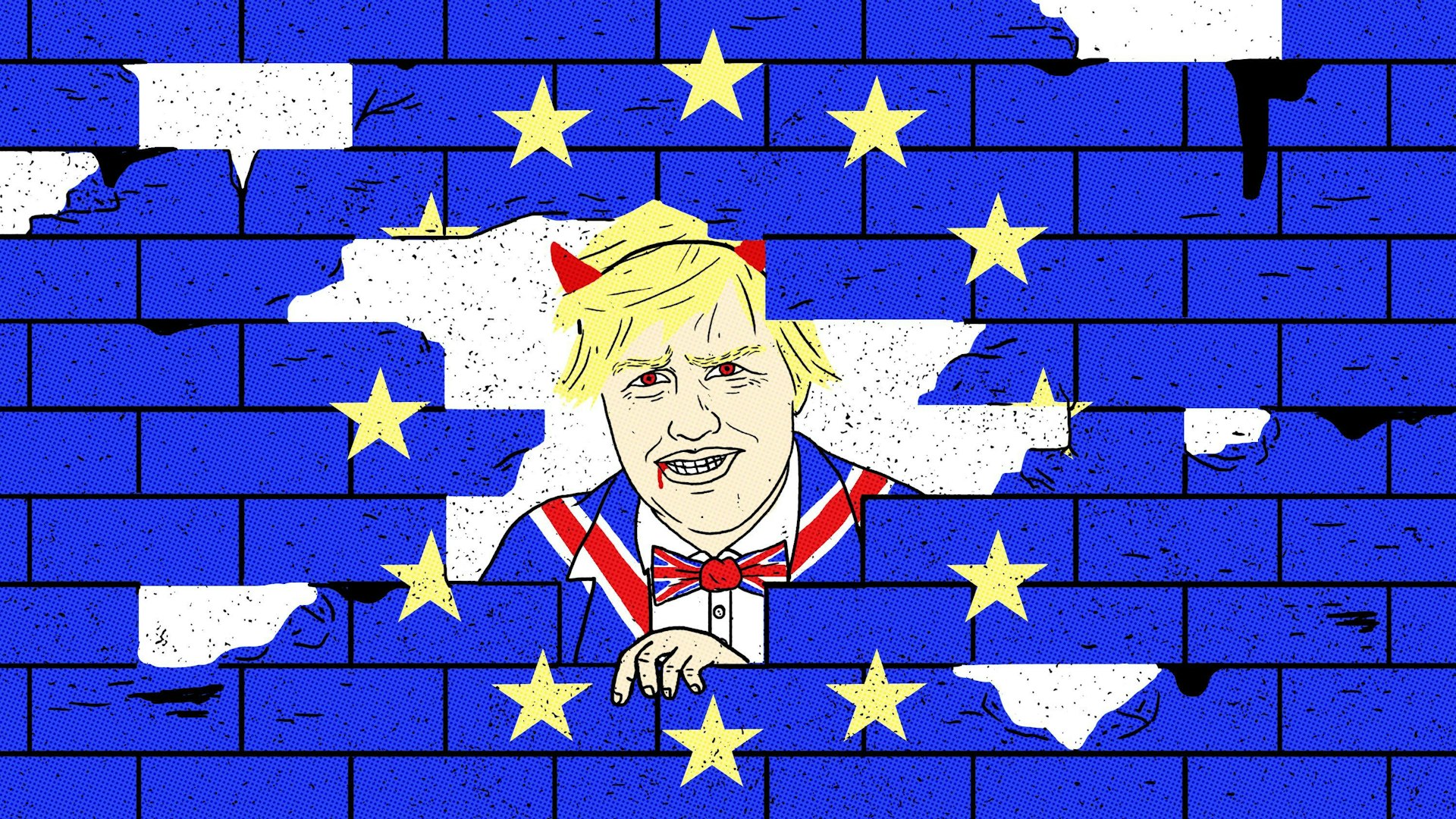

Remaining in the EU isn't pleasant, but this right-wing Brexit is worse

- Text by James Butler

- Illustrations by Laurene Boglio

You could be forgiven for wanting nothing more to do with the EU referendum. The official ‘leave’ camp are an unappetising combination of gurning shire racists, swivel-eyed libertarians and Tory misfits, headed by the desolate joke that is Boris Johnson.

The ‘remain’ camp is scarcely better: with little positive to say about the EU, it falls back on doomy prognostications about World War Three and a promise to be almost as harsh on migrants as the others. (Will there be quotas for the drowned and the saved?) Add to this a feverish, conspiratorial atmosphere, stoked to a white heat by exit campaigners and exploding in the murder of Labour MP Jo Cox by a long-term fascist, it’s understandable to want to turn your back on the whole sorry affair.

But you shouldn’t. It’s tempting to abstain: the political choices in this referendum are minimal, especially for those on the left. It amounts to a choice between a grim status quo, and exit from the EU under the leadership of the hard right, with a programme keyed to even harsher migration policy, erosion of basic labour protections, economic hand-waving and riding a continent-wide spasm of xenophobia. Conventionally, there are two ways of analysing how one might vote: either according to principle, or instrumentally, according to the effect a vote might have.

In reality, we make political decisions while weighing both criteria: what we believe in, and what we think is likely to happen. It is in the zone of effects that the most convincing arguments are made, and understanding the effects requires thinking about the effect of the vote in Britain and across Europe.

There are convincing reasons to distrust the EU: its treatment of Greece, its many unscrutinised procedures and rickety democracy, its inaction on the refugee crisis and its inbuilt orientation, since the Maastricht treaty, to privatisation and low social spending. This is not a referendum on the existence of the EU, however, but Britain’s membership in it. The few arguments made for a progressive exit, scarcely audible amid the din of Gove, Johnson and chums, concentrate on a judgement in principle on the EU away from the actual circumstances of the vote.

Where the consequences of the vote are considered at all, it is at the end of a series of improbable hypotheticals: if a Corbyn government can get elected, if it can pass ambitious constitutional reform, if it can pass nationalising legislation for several industries, then it might have to confront EU legislation and membership. But it would do so from a position quite different to Greece’s and in a Europe changed by the election of a left government in one of the EU’s core member states; with Labour’s coup-mongers looking for any chance to oust Jeremy Corbyn and briefing against him in the press, if you’re willing to gamble on that option I’ve a bridge I’d like to sell you.

In any case, that’s not the argument being had in the political mainstream, or in the media. As expected, the referendum is being turned into a proxy vote on migration, this being the Leave camp’s main argument. This repeats a pattern noticeable across the EU, as in Denmark at the end of last year, where a referendum on security co-operation failed largely because of popular suspicion it would bring Denmark in line with European migration and asylum policy.

In its wake, Danish parliamentarians passed a law not only decreeing confiscation of refugees’ valuables – a measure that made headlines – but effectively creating asylum ghettoes and heavily restricting rights to family reunion. Despite the low number of refugees actually taken by Britain, the atmosphere in which the referendum has been conducted makes similar laws feasible here; the Leave campaign has left the status of EU migrants already here an open question, but Gove’s floating of a points system makes uncomfortable reading.

It is important, too, to consider not just legislative but social effects of migration-oriented campaigns: what Theresa May once called a ‘hostile environment’ for migrants, from tabloid headlines to street harassment.

If the treatment of migrants is enough to give a progressive voter pause, the political consequences of an exit are even more worrisome. You hardly have to be a paid-up capitalist to recognise that the financial stress from leaving the EU will endanger a lot of people who are barely clinging on in a stagnant recovery. But it’s more dangerous than that: Cameron would not survive a ‘leave’ result, but his successor would be (if imaginable) worse.

Vote Leave, and especially that sinister marionette, Michael Gove, have spent the referendum building on a popular distrust of elites and experts which has rankled away for two decades, boosted by their inept handling of the 2008 crisis. In further chipping away at any basic trust in the possibility of politics (half of Leave voters think the referendum will be rigged) he prepares the ground for an English Trump or Berlusconi in the person of Boris Johnson. The other possibilities are equally grim: Theresa May, George Osborne.

It is true that a vote to leave would force the British political system into crisis, removing its preferred scapegoat (Brussels!) and putting its dysfunction into the spotlight. But not all crises are good for a progressive politics, especially when the groundwork for them has been laid by the right. Giving the Tory party the opportunity to reshape decades of legislation, as a budget-stretched Whitehall finds itself with the gargantuan task of reviewing, replacing or reforming previously directly-implemented EU directives, seems a huge risk with little chance of positive outcomes.

There are other arguments we might make here: that the young ought to turn out because they have to live far longer with the consequences, and are far more pro-European but less likely to vote than the 65+; that the current structure of the global economy makes either splendid isolation or socialism in one country a nostalgist’s fantasy; that Brexit will be interpreted across the EU as a rejection of its migration policies from the right, and a boost to xenophobes across the continent.

I do not like the EU: I’ve written elsewhere that I think the economic and political dilemmas it faces are severe and its conduct often repulsive; its benefits – a timid and conservative prefiguration of what a genuinely free movement of peoples might look like – sit alongside its exclusion of refugees and grubby deals with authoritarian governments like Turkey. But because its crises are so intractable, it will have to face them over the next decade, whether it wants to or not.

To vote to exit, and give succour to movements across the continent which would seek the most retrograde and conservative solutions to those problems, is the very height of political folly.

James Butler is a writer and editor at Novara Media. He lives and works in London. You can follow him on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.