A glimpse inside America’s trans community in the ’70s

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Jeffrey Silverthorne

During the early 1970s, American photographer Jeffrey Silverthorne (1946-2022) began visiting Homestead – a Providence bar that catered to the transgender community when it was still deeply underground. Blessed with a gentle nature, Silverthorne crafted portraits of the people he encountered out on the town as well as in the privacy of their homes.

Then in his mid-20s, Silverthorne was also was also photographing dead bodies inside a morgue with the same tenderness and respect he gave to the living. The series took root after Silverthorne met Diane Arbus and asked if she had ever photographed a corpse. Arbus demurred, saying, “No. Why would I? There’s nothing interesting going on there”.

Silverthorne felt otherwise, believing that death held its own beauty and truth. The camera became a tool through which Silverthorne could connect us across the vast divide, helping us to look at those who might overwhelm, unnerve, or challenge our beliefs.

Jim, La Villa Blanc, 1971

“Jeffrey was never fearful of showing you things you didn’t necessarily want to look at,” says Burt Finger, Silverthorne’s long time gallerist and friend. “I have a huge amount of respect for an artist that is so dedicated to what he does and doesn’t think about monetary – or any type – of gain. Jeffrey slid under the radar and never got the acclaim he should have.”

To honour Silverthorne’s singular legacy, Finger recently organised an exhibition, In Memoria, which brings together selections from his archive alongside photographers Jesse Alexander and Paul Greenberg, who also passed this year.

Prior to becoming a gallerist, Finger was a photographer and educator long familiar with Silverstone’s work before the two finally met in 1998. “Jeffrey was one of those artists who was dedicated to his mission. He had a focus and looked at things that weren’t easy to sell,” says Finger, who was not deterred by the challenges of representing Silverthorne.

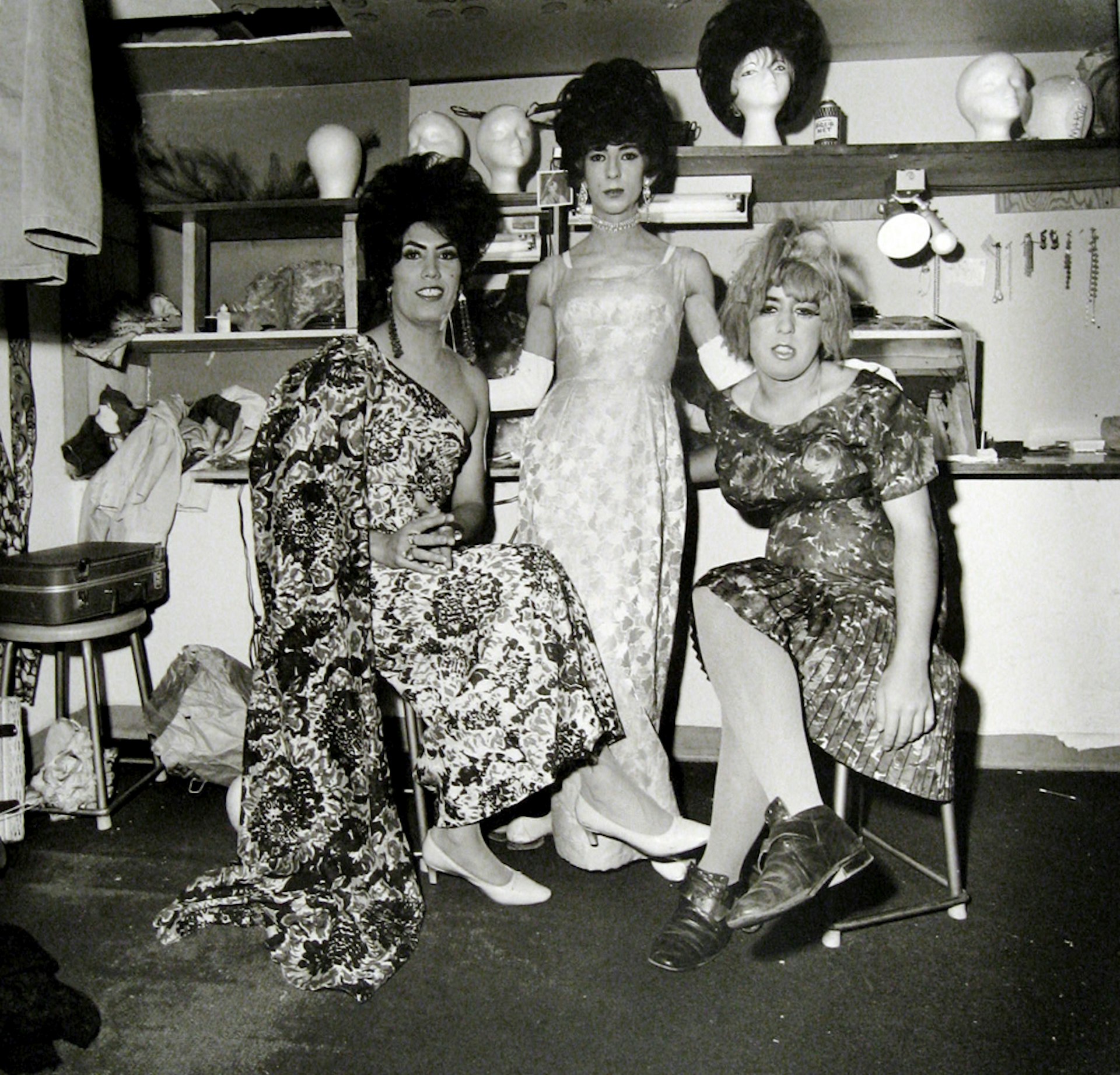

Dressing room, La Villa Blanc, Albuquerque, 1971

Rollin and Dog, 1972

Whether photographing the trans community, sex workers on the Mexico border, bullrings, carnivals, or Boystown, Silverthorne brought empathy to his encounters with people living on the margins of society. “Jeffrey didn’t think of the people he photographed as abnormal; it was just another part of life. He was more focused on the pain of life than the joy. I think in some ways, he was expressing some of the pain that he felt,” Finger says.

“I respected his vision, although I could see sometimes how dark it was. But you wouldn’t know that by talking to him because he was a very positive person. I will tell you this: Jeffrey didn’t look how you would think. He looked like your typical professor, a mild-mannered intellectual who always wore a sports coat.”

Silverthorne preferred to take the position of observer, bearing witness to beauty that often goes untold. Finger remembers how, when he took him to go fishing, the photographer refused to put down his camera and pick up a rod. “All he would do is take pictures,” Finger says. “He was such a sensitive guy.”

Twiggy / Pochahontas, 1972-1974

Mistra and Monique, La Villa Blanc, 1971

Dougie, Jackie and Rollin, 1972

Jim and Friend, La Villa Blanc, 1971

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.