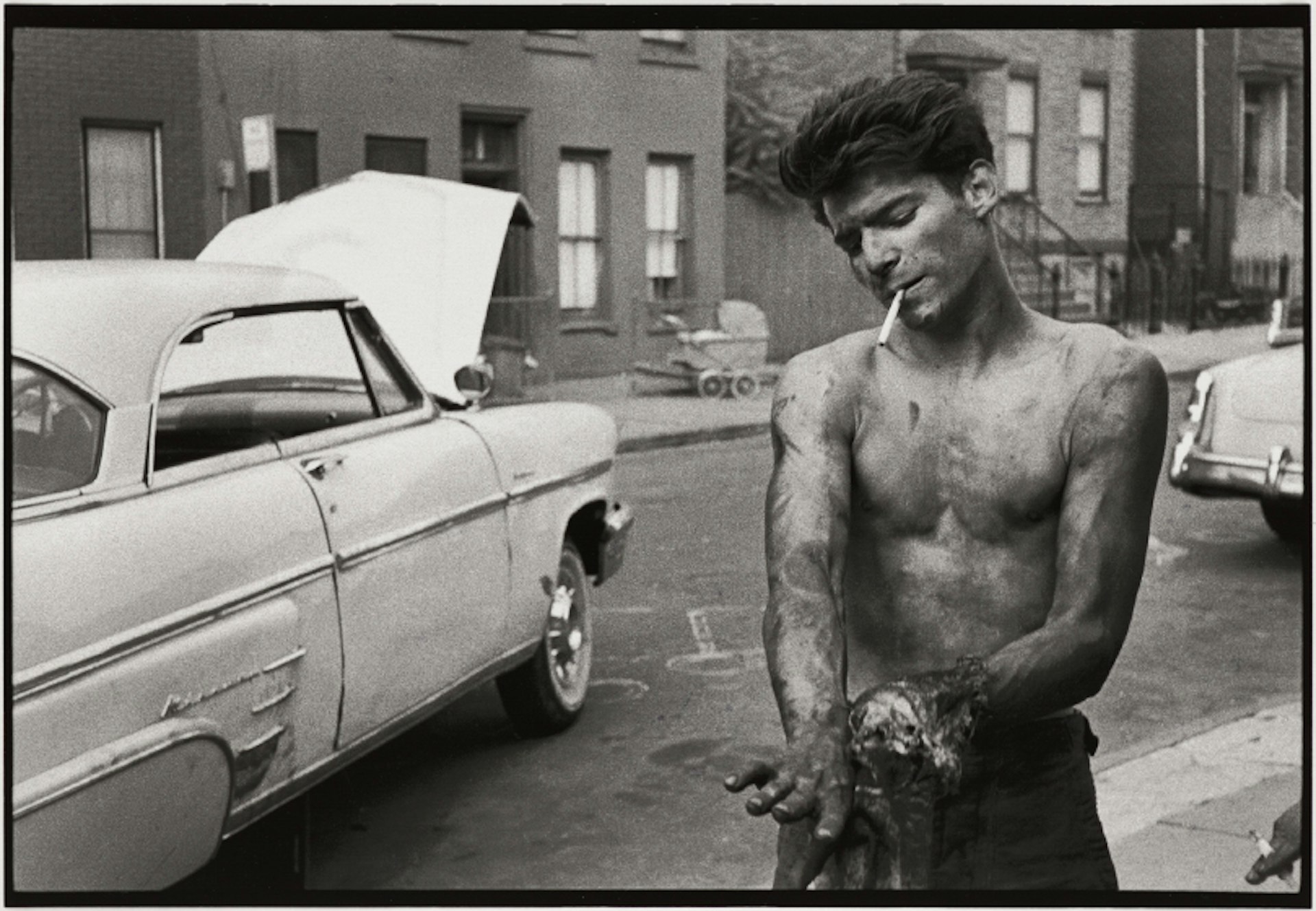

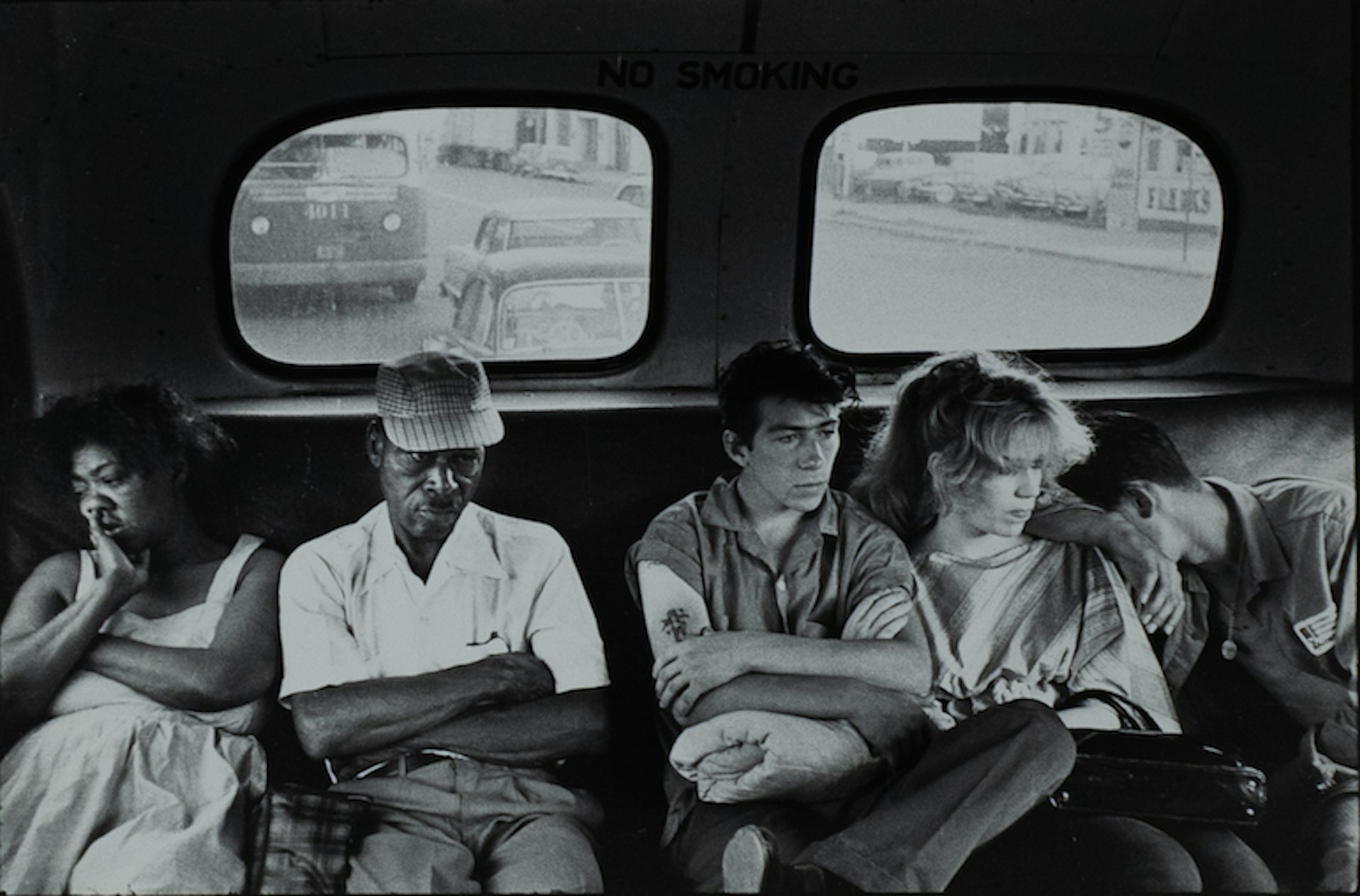

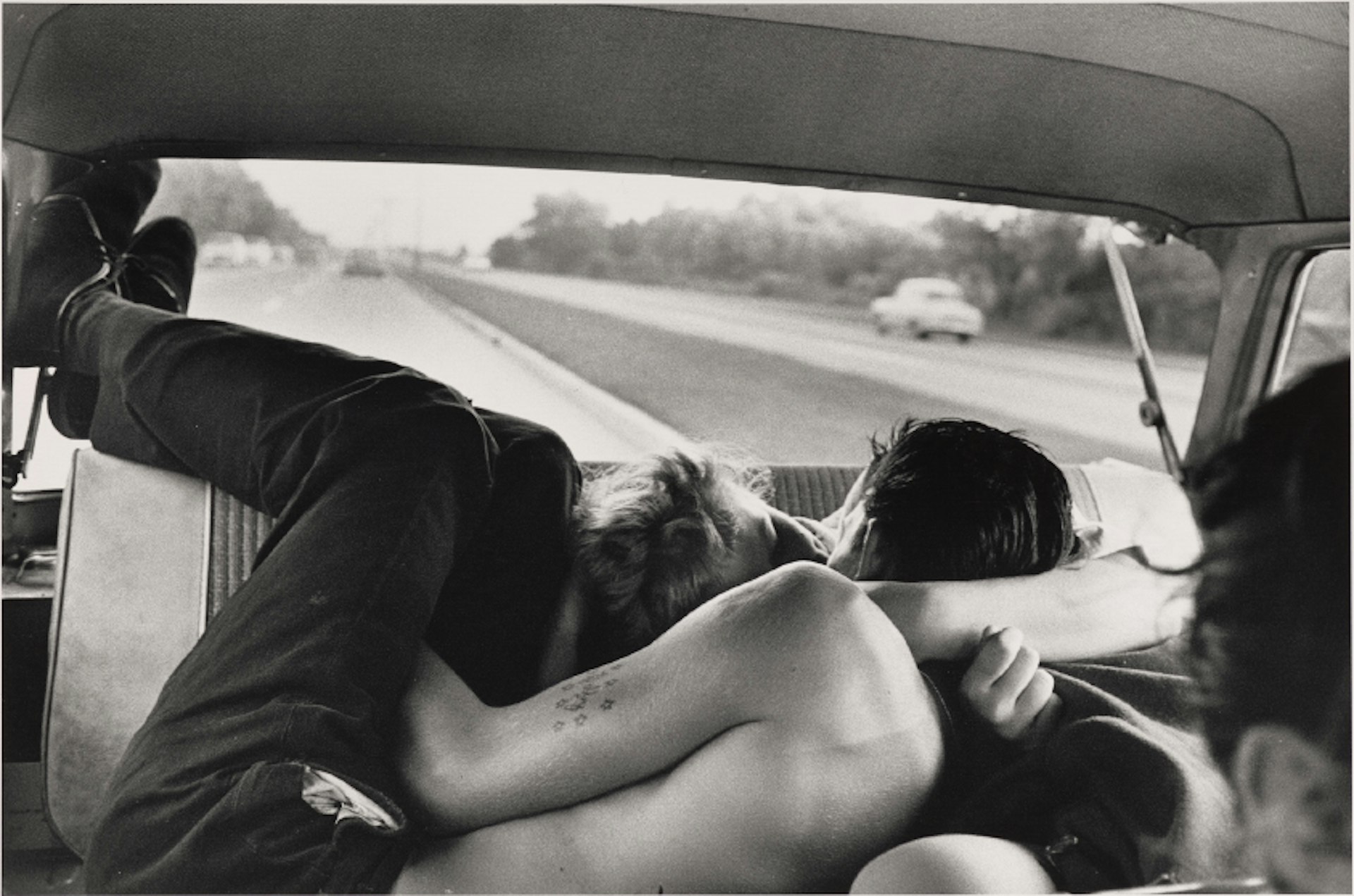

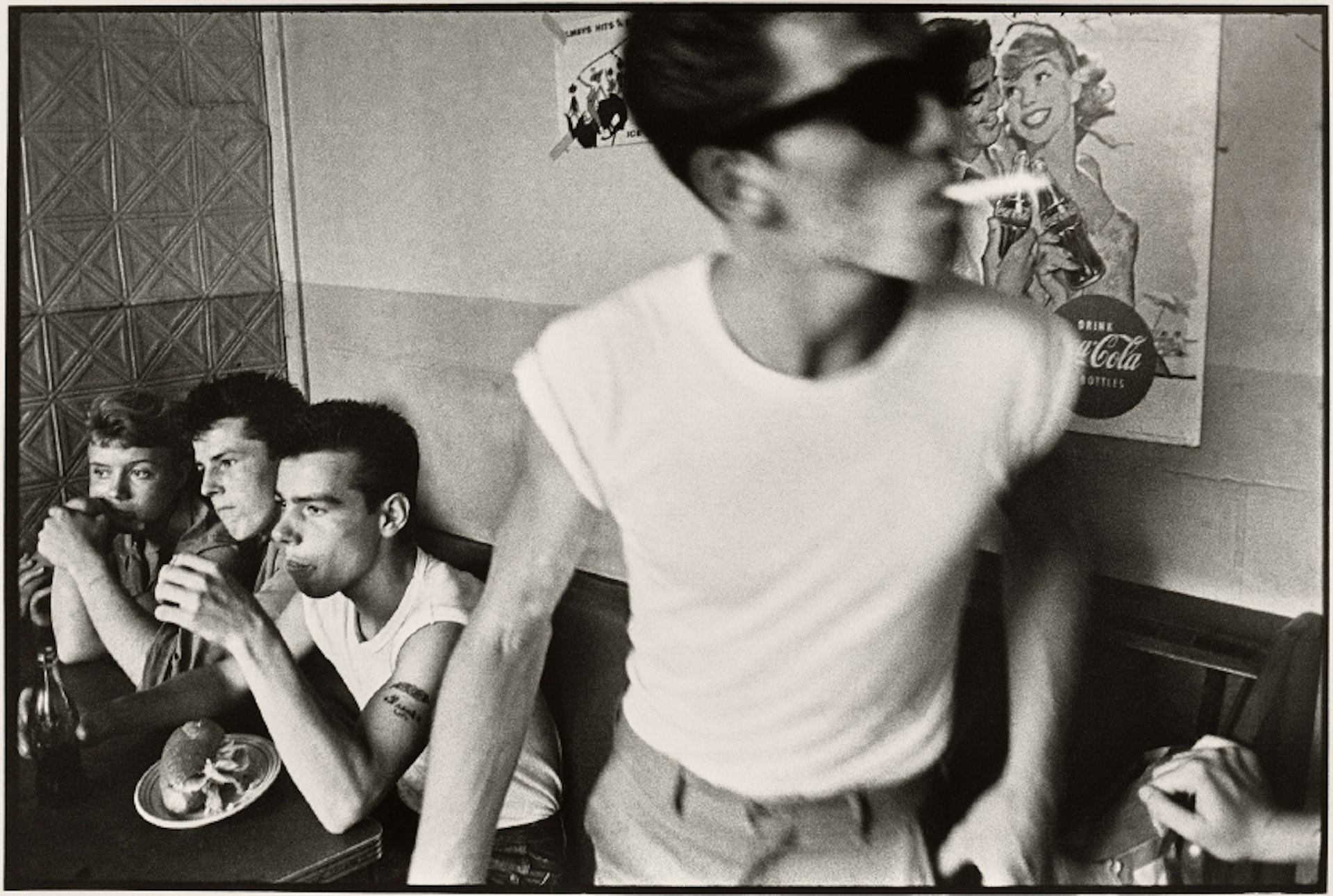

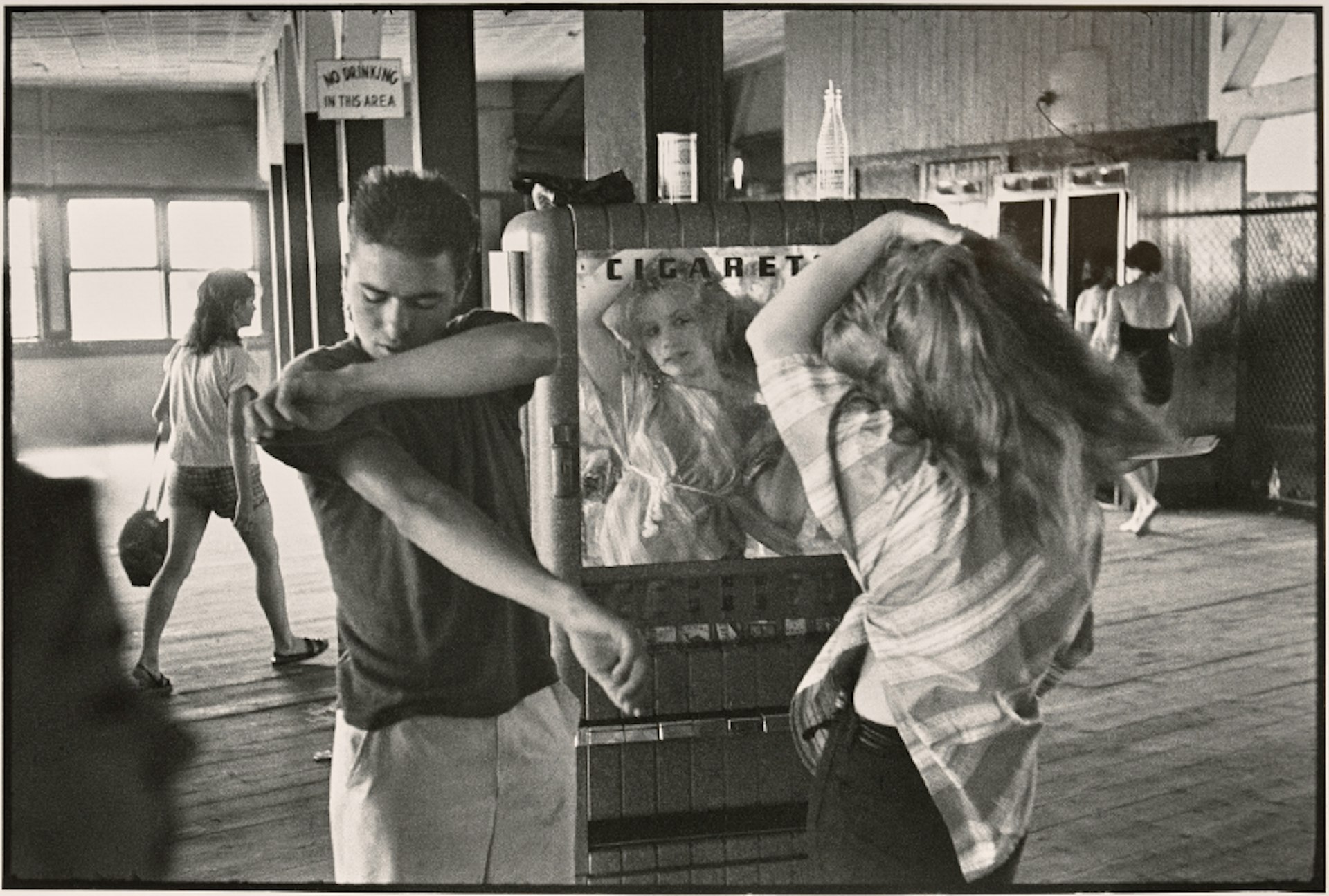

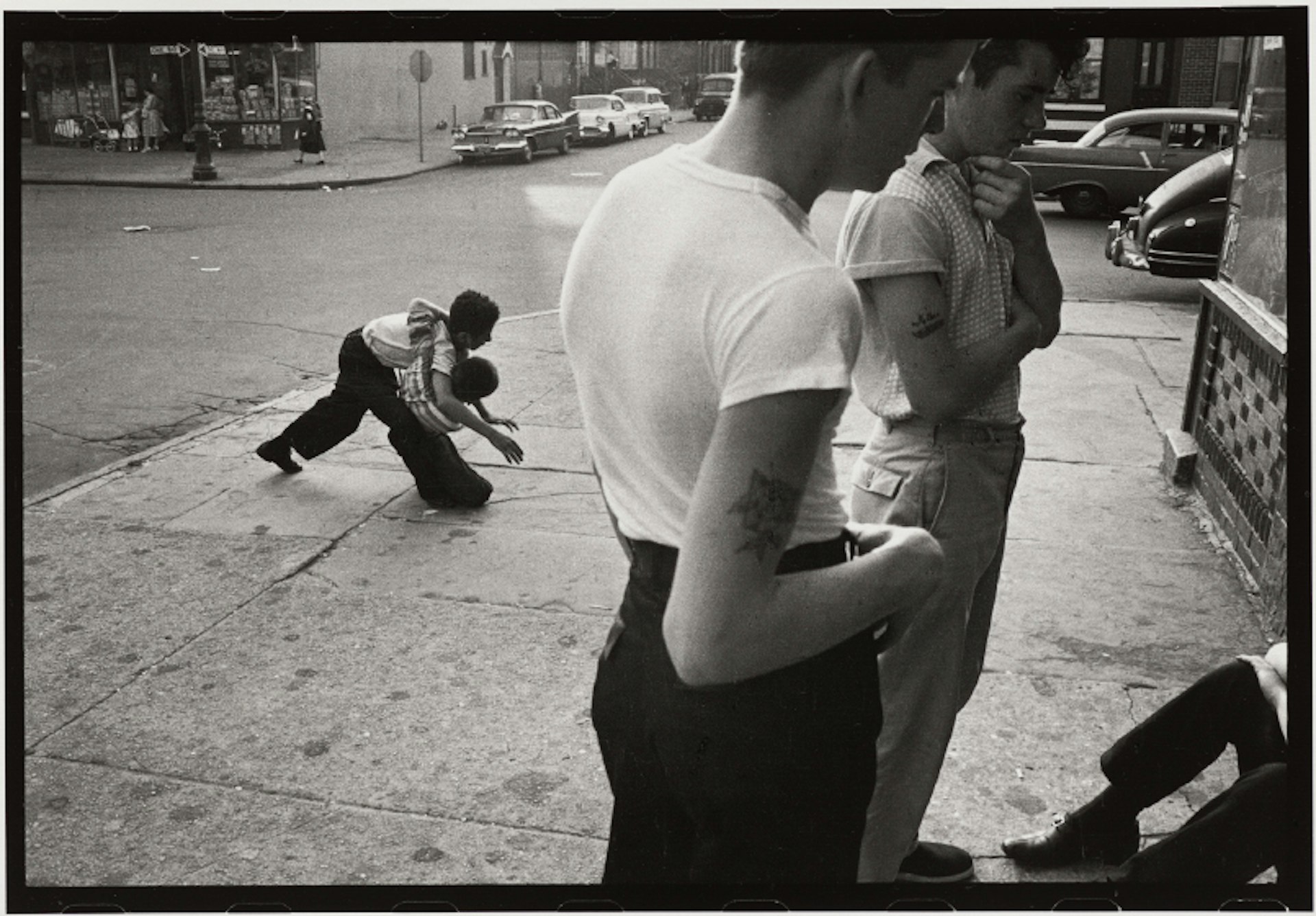

A moving portrait of a Brooklyn teen gang in the '50s

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Bruce Davidson

The postwar boom in America cast a golden glow around the 1950s, the first decade when youth culture came into vogue. With the advent of television and Rock ‘n’ Roll, Hollywood quickly discovered a new archetype: the disaffected “rebel without a cause.” Co-opting working class aesthetics, Hollywood transformed the image of disenfranchised teens into anti-heroes for a new generation coming of age.

But the reality was much bleaker than a James Dean flick. Gangs provided what the community could not: a sense of family and belonging for those living on the margins. By the 1950s, juvenile delinquency was on the rise, and the mainstream media began targeting them as new class of criminals to be vilified.

After joining Magnum Photos in 1959, Bruce Davidson, then 25, read a newspaper story about white and Puerto Rican street gangs rumbling on the streets of New York City and decided to investigate.

Through a government-sponsored ‘Youth Board’ of social workers, Davidson was introduced to the Jokers, a group of Catholic school students and dropouts aged 15 based in Park Slope, Brooklyn – then a predominantly Irish and impoverished neighbourhood.

“Davidson related to them as an ‘outsider on the inside.’ He had just returned from Army service in Europe and said he wanted ‘to take pictures of their wounds from a gang war,’” says Amy Raffel, Andrew W. Mellon Interpretation Research Fellow at the Queens Museum, where the exhibition Bruce Davidson: Outsider on the Inside is currently showing.

The concurrent exhibition, Bruce Davidson: Brooklyn Gang focuses exclusively on this chapter of the photographer’s work, providing a poignant, thoughtful counterpoint to Hollywood and media portrayals of the issue of juvenile delinquency.

“Davidson said that he could relate to their feelings of failure, isolation, and hopelessness,” Raffel says. “He didn’t frame them as a problem, or as a burden, or compose his photographs to elicit sympathy or social action. He wanted to present a more well-rounded view of their lives.”

Davidson spent 11 months with his subjects, embedding himself within the group to earn their trust and move among them freely in order to create a candid portrait of gang life that went far beyond Hollywood and media stereotypes.

“In the end, Davidson asserted that the series is not about gangs, but about teenagers with few prospects in life who suffered from neglect and boredom, not delinquency,” Raffel says.

Brooklyn Gang has gone on to become one of the definitive works of 20th-century documentary photography. “His immersive and slow-moving approach and focus on youth helped pave the way for photographers in later decades,” Raffel says, citing the work of photographers Larry Clark, Nan Goldin, and Rineke Djkstra, among others.

More than 60 years later, Brooklyn Gang still speaks to the experience of native New Yorkers struggling to survive amid a world that doesn’t care if they live or die. “Davidson’s work is compelling because it is so relatable,” Raffel says. “He shows that ordinary life can be beautiful, and dignified, no matter who you are.”

Bruce Davidson: Outsider on the Inside is on view at the Queens Museum through January 17, 2021. Bruce Davidson: Brooklyn Gang is on view at the Cleveland Museum of Art through February 28, 2021.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.