A tender portrait of Chinatown New York in the 1980s

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Bud Glick

Back in 1980, Jack Tchen and Charlie Lai founded the Chinatown History Project (now the Museum of Chinese in America): a community-based organisation that would document, record, and preserve the history of New York’s legendary neighborhood. Due to changes in immigration laws of the mid-1960s, Chinatown was undergoing a period of transition as a new wave of émigrés from Hong Kong, Taiwan, and China arrived in the city. “Jack and Charlie felt that the memories of first-generation ‘old-timers’ would be lost without oral history, photo documentation, research, and collecting efforts,” says American photographer Bud Glick, who joined the team in 1981.

At first, Glick struggled to get beyond the superficial aspects a tourist might encounter just passing through. “I was an outsider, which created a barrier that I had to overcome,” Glick says. “But I was able to make and follow connections. There was usually a very positive response when I gave people a print back. With time and persistence, I learned more about the community on the street, in apartments, the garment factory, and the Chinatown Senior Center of Mulberry Street.”

As doors began to open, Glick made his way inside a rapidly changing world to create the series Interior Lives: at New York Chinatown in the 1980s. Over a period of three years, Glick built relationships with residents, gaining their trust, to create a multi-generational portrait of a community shaped by racist immigration laws.

In 1882, the US government passed the Chinese Exclusion Act to curtail immigration, only to repeal it in 1943 when the US sought to align with China against Japan in World War II. However, numerous discriminatory laws remained in place until the Immigration and National Act of 1965.

As a result of xenophobic government policy, many families spent decades apart. Glick shares the story of Mr. and Mrs. Chow, who didn’t see one another for more than 30 years. When they finally reunited, neither recognized their spouse. But they spent their final years together, Chow’s love for his wife radiating in Glick’s portrait of the couple at home together.

Big Tall Chin, Sam Wah Laundry, Bronx, 1982

Chinese New Year, Bayard St., 1984

The older generation, primarily men, lived together in bachelor apartments, which Glick describes as “a quintessential part of the Chinese immigrant experience”. Spending time with these men in their homes, Glick gained a deeper understanding of how their lives had been impacted by sinophobia.

“With their trust and my understanding came the great responsibility to tell their story in photographs,” Glick says. “Exposure to the reality of other people’s lives always challenges our preconceived notions and can open our minds to seeing the world from someone else’s point of view.”

At a time anti-Asian racism is on the rise across the United States, Glick’s work provides a powerful and poignant counternarrative. “The othering of Asians is nothing new,” he says. “Though it is only photography, I hope that my work can stand as a refutation of that bigotry.”

Bachelor Apartment, Mr. Ng, 68 Bayard St., 1982

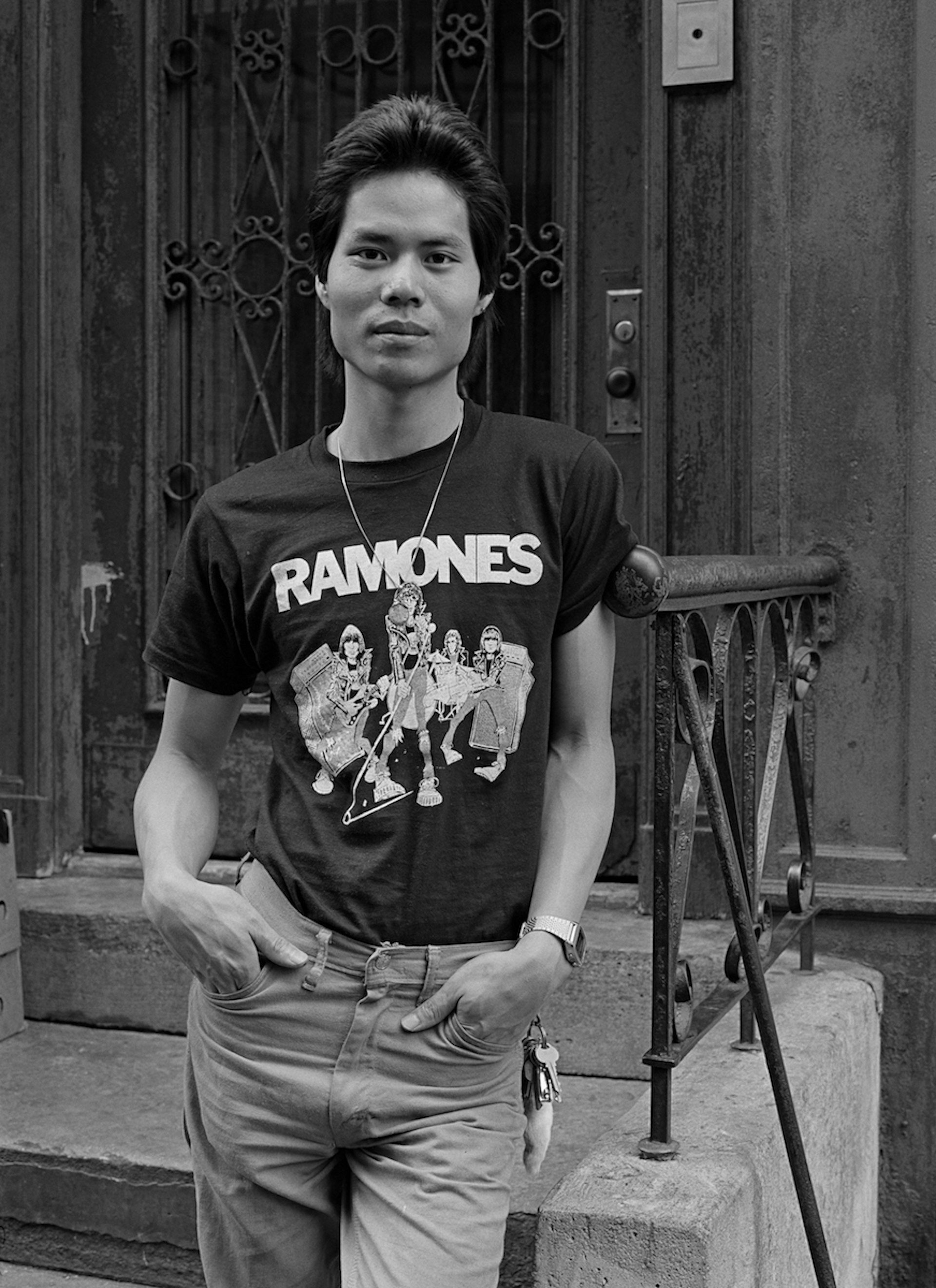

Tony, Catherine St., 1981

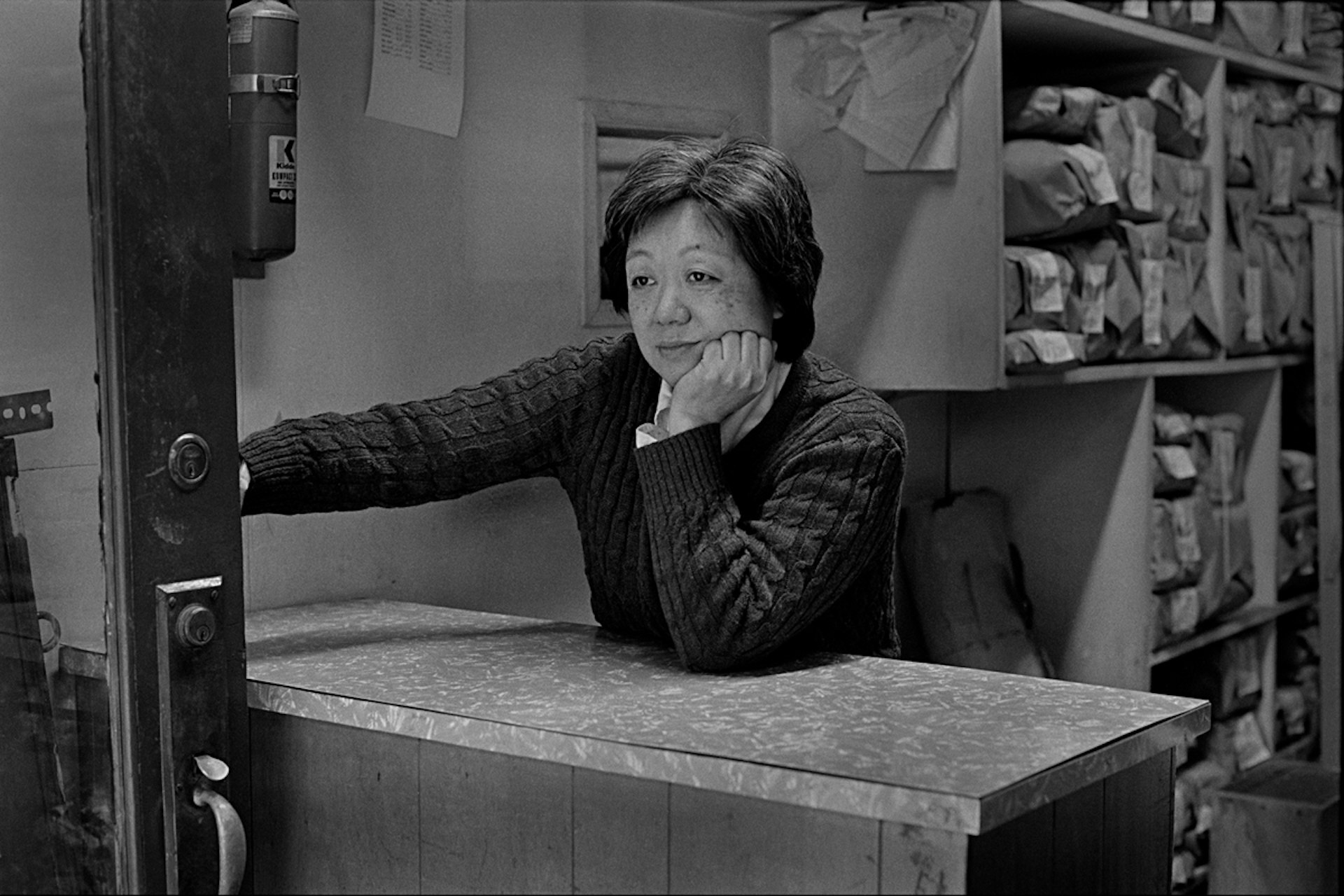

Club Lunch sandwich shop. 2 East Broadway, 1983

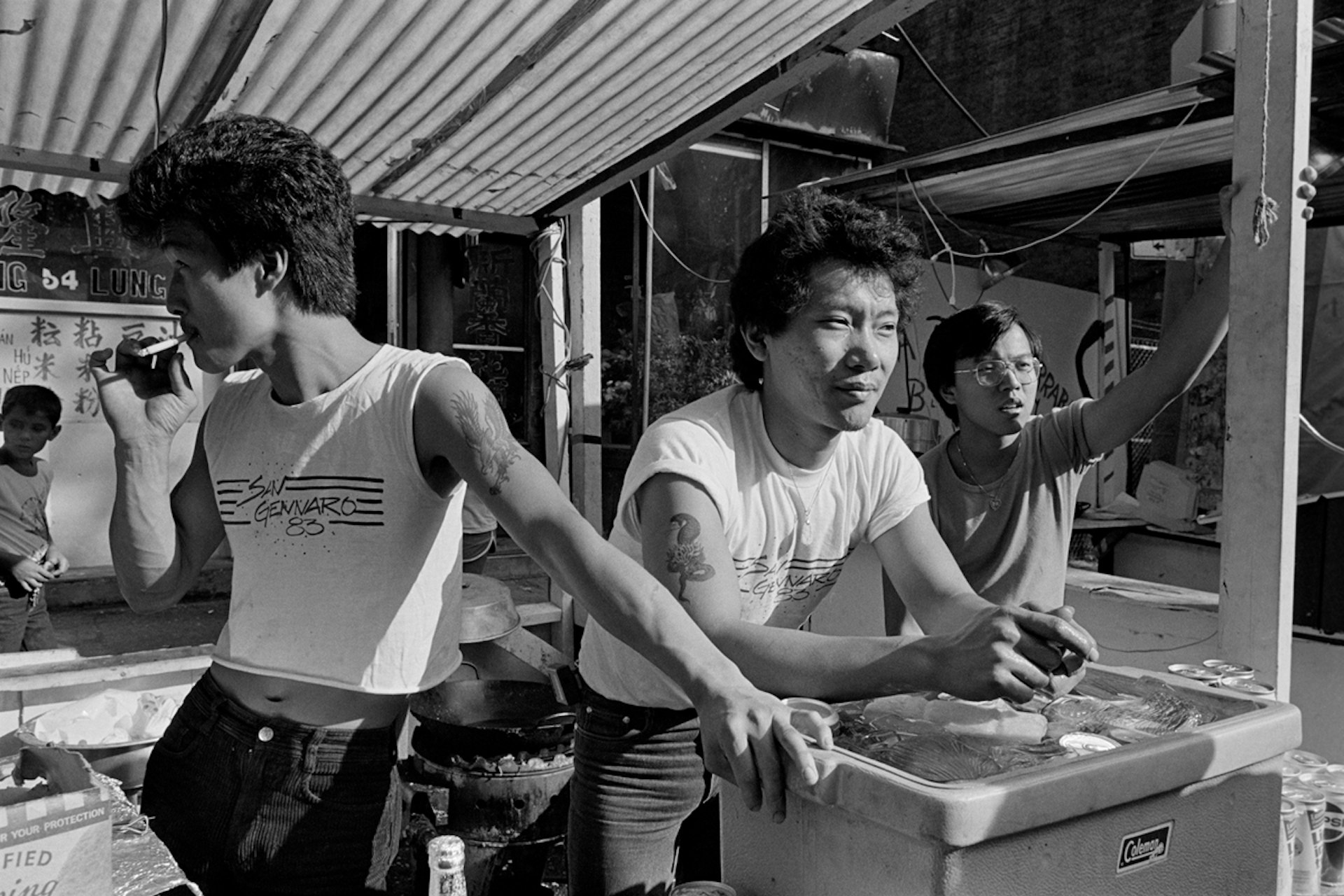

San Gennaro Festival, 1983

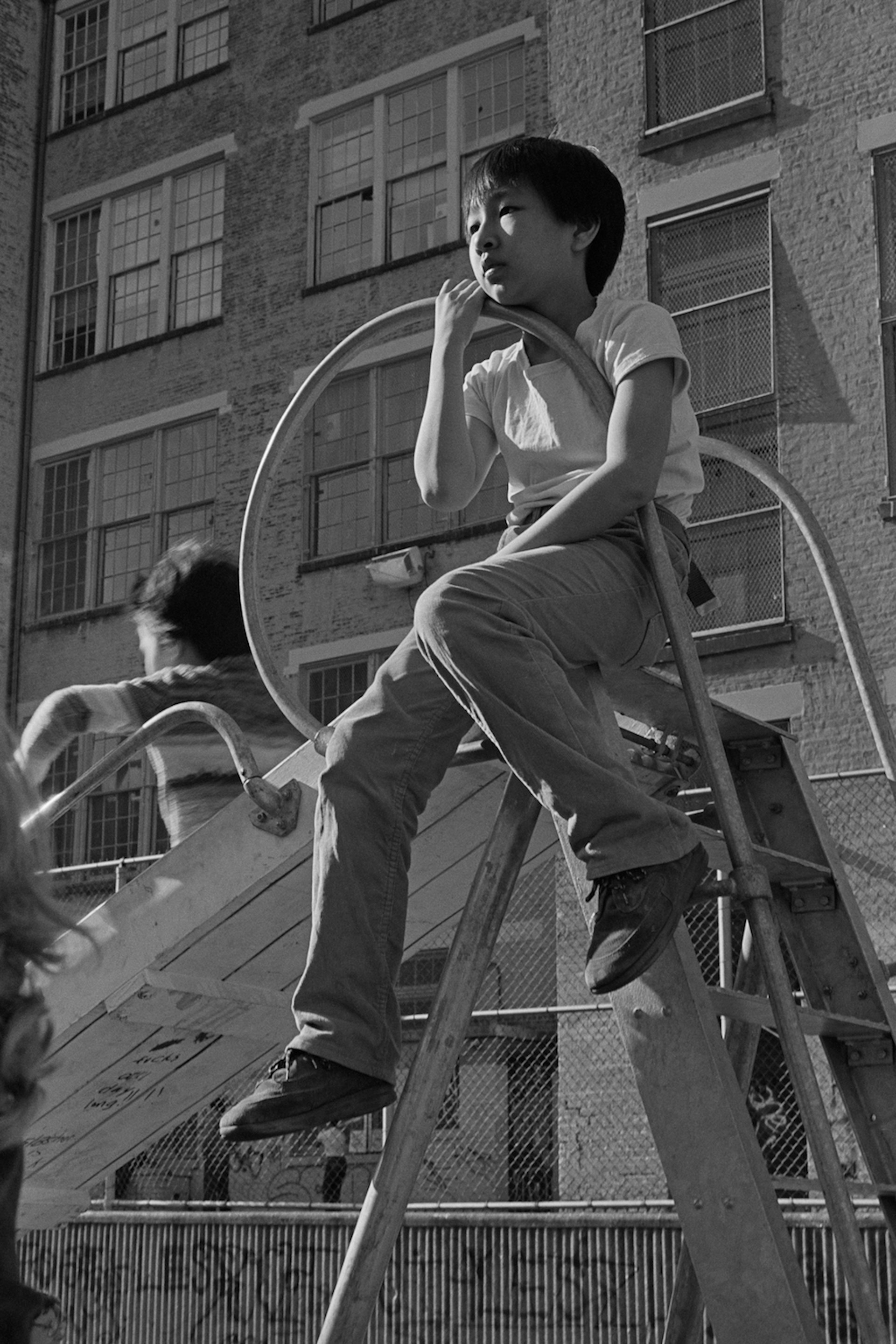

PS 1 playground, 1982

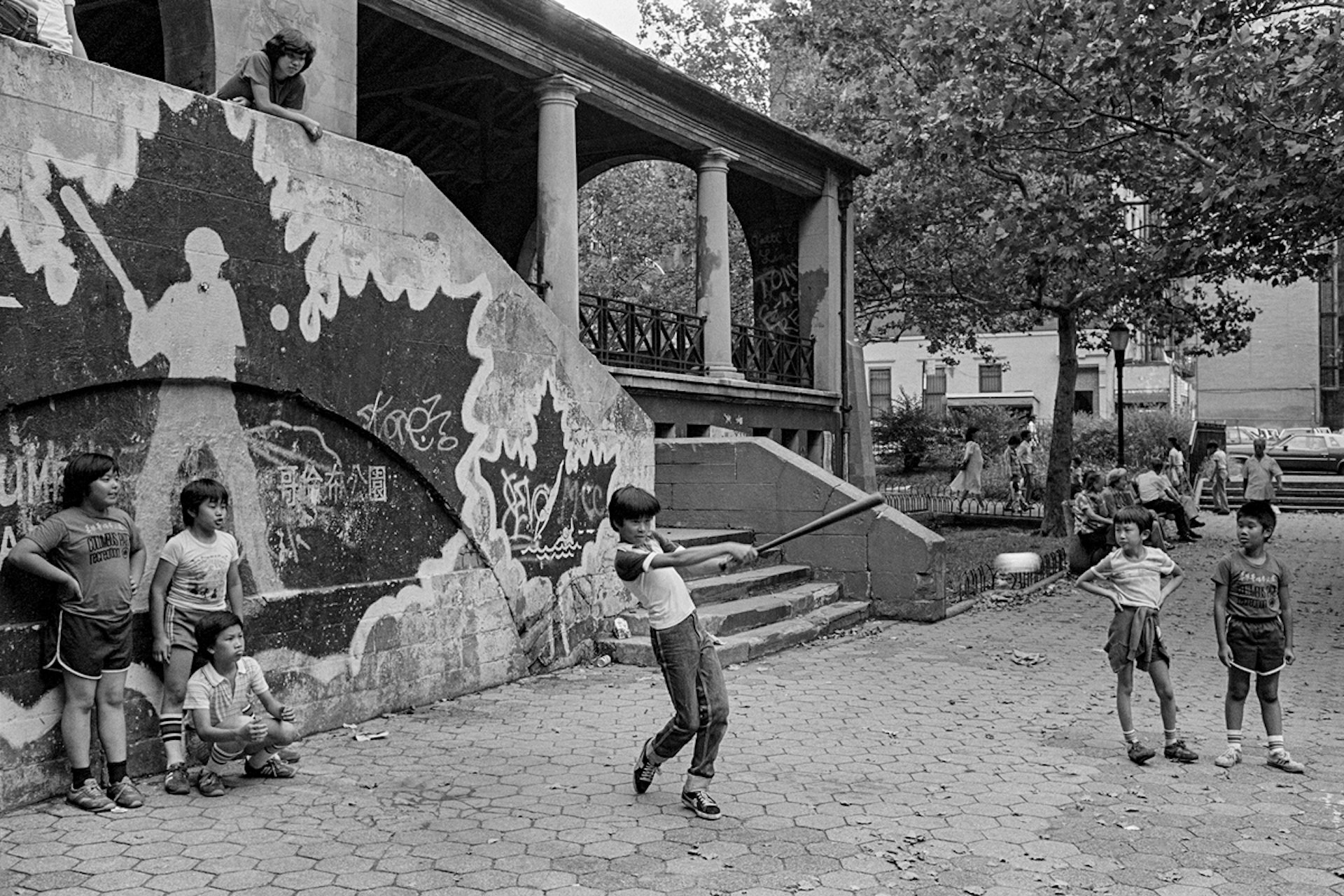

Columbus Park, 1982

Columbus Park, 1982

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Instagram.