Artists and architects unite to imagine creative solutions to the global housing crisis

- Text by George Kafka

Across the globe, capital is driving housing development goals away from social priorities, feeding the gradual death of our city centres as they progress from spaces of culture and contrast to homogenous tourist-sites and business districts. From New York to Rio de Janeiro to Johannesburg, housing solutions based around gated neighbourhoods, tourist-friendly infrastructure or “regeneration” projects leave little room for the maintenance of that which made these areas desirable in the first place: community.

Berlin is no exception to this trend. Renowned for its low rents and appealing creative culture, Berlin is becoming a victim of its own success. Increasingly scarce affordable housing and a creeping gentrification is transforming neighbourhoods from residential communities into transient hype zones.

However, tackling these issues head on is a major exhibition at the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of World Culture) in Berlin, under the title Wohnungsfrage: literally, ‘housing question’. By bringing together artists and architects from cities across the globe and pairing them with social initiatives based in the German capital, the exhibition has provided a space to discuss, design and create new architectural solutions to the issues facing the city.

“Ever since the neoliberal turn and the withdrawal of state politics from the field of housing, architecture became less and less interested in housing,” explains exhibition curator Nikolaus Hirsch. “Now, in the context of increasingly polarised economic and social debates, the housing question is back on the agenda.”

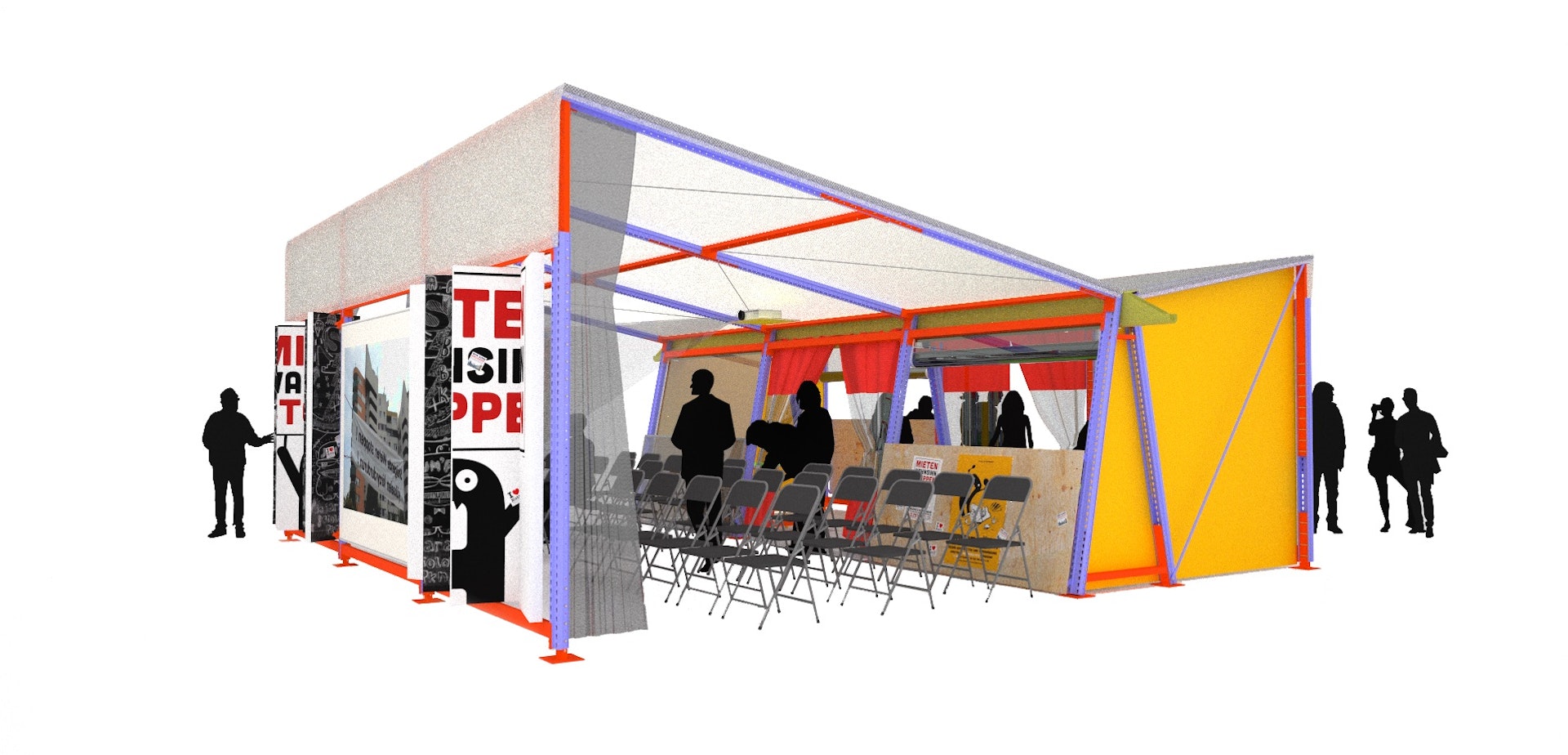

One project for the exhibition was a collaboration between Kotti & Co – a tenants initiative founded in the heart of Berlin in protest against high social housing rents – and Estudio Teddy Cruz + Forman – a studio based in San Diego who work with informal communities on the San Diego-Tijuana border. The two organisations designed and built a Retrofit Gecekondu, a lightweight shelter made from off-the-shelf industrial storage elements, which serves as a flexible space for different community functions: from market stalls to an assembly hall for a temporary urban parliament.

While not a direct housing solution, Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman argue that there is much more to housing than the domestic object itself and thus the Gecekondu represents a space for community creation, participation and planning: “We need to reclaim those spaces around housing that can be spaces of local productivity, enabling tenants to improve their own lives and have a say in the future of their own planning.”

The Retrofit Gecekondu, 2015 © Estudio Teddy Cruz + Forman

The Gecekondu plays to the strength of the community of Kotti & Co. and creates a space for the realisation of everyday community activities, and a public forum for the bottom-up planning of the future of the city. As Cruz and Forman argue, “The future of the city will not be led by buildings, but by the fundamental reorganisation of socio-economic relations.” It is from the Gecekondu that they hope this new vision for the city will emerge.

This approach of facilitating, rather than prescribing, by Teddy Cruz and Fonna Forman represents a paradigm shift in the role of architects and the social production of housing and community. Back when architects were renowned for designing for social good (the “heroic” European Modernists of the ‘20s, Constructivist Soviet architects of the ‘30s, post-War London County Council architects, etc.) they were also criticised for imposing their own utopian values upon the built environment, setting out in concrete an inflexible ideal that bowed to the whims of an all-powerful architect. In the Gecekondu project, the power to imagine, design, and plan the urban environment lies firmly in the hands of the people who occupy it.

Kotti & Co + Estudio Teddy Cruz + Forman: Retrofit Gecekondu © Jens Liebchen / Haus der Kulturen der Welt

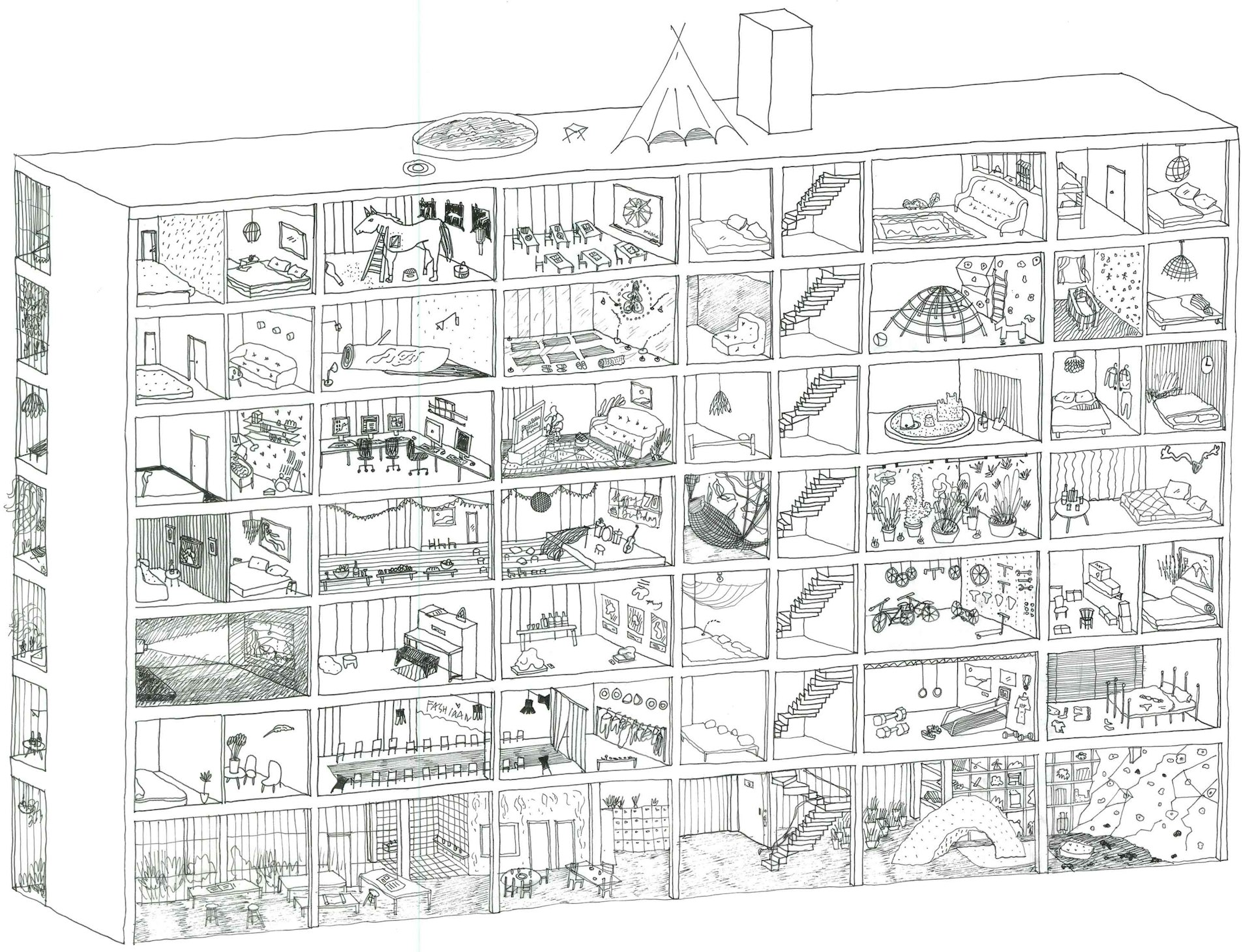

There is a similar approach to Teilwohnung, another project to come through the Wohnungsfrage exhibition which brings together Assemble – the Turner-Prize nominated architecture/art collective based in London – and Stille Straße 10 – a cooperatively owned community centre occupied by elderly squatters in northern Berlin. Teilwohnung envisions an apartment block that is founded on communality and flexibility. Each apartment is divided into two halves: one which contains the basic infrastructure of the house (kitchen, bathroom etc.) while the other is an open, un-assigned space rented from the building co-op which can be used differently according to the needs of the occupants.

© Assemble, 2015

Drawing from the changing life circumstances of the elderly residents at Stille Straße 10, Assemble have designed a building for building; for the process of living and the change which is inherent in that. According to Maria Lisogorskaya of Assemble, this not only improves the lives of inhabitants, but also strengthens community ties: “There is a strong sense of communality which takes root in the building, through the collective experience of building. This is a point of greater reliance on each other, where you learn from others, help others move in, but also where you might eat together, drink together.”

The split of domestic and communal/rented spaces in the unit also creates cheaper housing as only the basic shell of the building is constructed, the rest is built up by the residents. Assemble took inspiration for this adaptable form of living from the residents of Bonnington Square, where simple terraced housing has been adapted to create idiosyncratic and personal interiors since the South London neighbourhood was first squatted in the 1980s. Behind these initiatives is a notion of tenant autonomy, where changes in personal and communal circumstances are facilitated in the function and design of the residential building.

Assemble, Teilwohnung, 2015, 1:1 model, © Jens Liebchen / Haus der Kulturen der Welt

While the projects on display at Wohnungsfrage are all models, the exhibition provides an important arena to demonstrate the possibility of community oriented urbanism and a space for architectural enquiries into the state of housing developments in our cities. These are essential discussions if we are to save our cities from a state of Disneyfication and our communities from a fate of total destruction.

George Kafka writes for uncube, an online progressive architecture magazine based in Berlin.