Dolls, women and protest: Why we still need feminist art

- Text by Grace Banks

- Photography by Laurence King

Pictures of women exist everywhere. In art galleries, public phone booths, Instagram feeds, pornographic websites, fashion blogs, magazines and advertisements on buses – the exposure of women’s bodies dominates some of the world’s most visible and highest-grossing industries. This has made understanding images of women’s bodies confusing. Who are more important – the women in the top-shelf magazine, or the women in the glossy magazine? Who gets to decide, and who has created these images anyway?

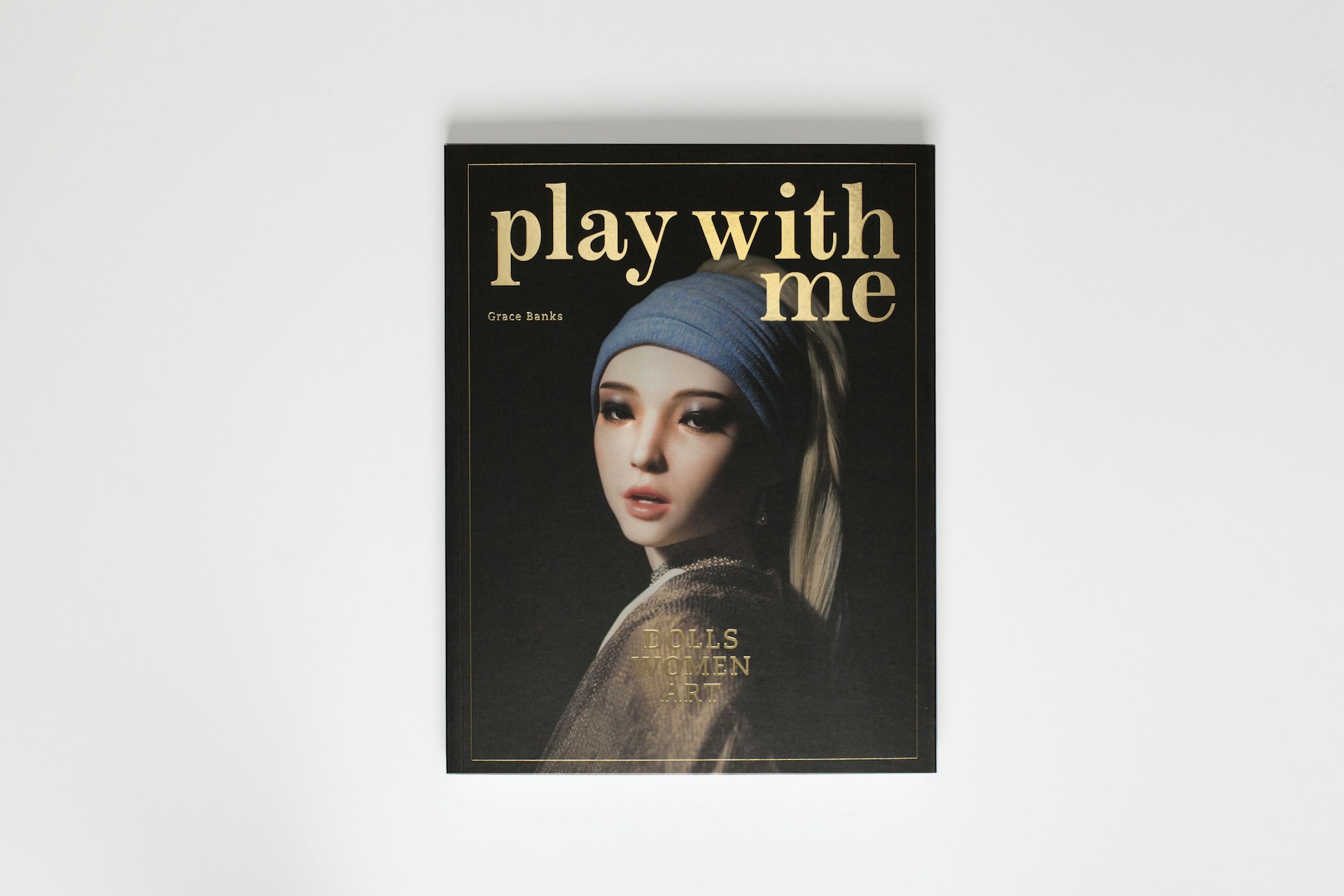

In my book Play With Me: Dolls, Women, Art, I wanted to call out the increasing commodification of feminism by talking to a group of artists that focus on the appropriation of women’s bodies. The artist Pandemonia is the perfect example. She acts out what the writer Natasha Walter, in her book Living Dolls: The Return of Sexism (2010), called the infiltration of “dolls” into society. “The fusion of the woman and doll at times becomes almost surreal,” she says. “For more than 200 years feminists have been criticising the way images of feminine beauty are held up as the ideal… Though far from fading away, the images have become narrower and more powerful than ever.”

Pandemonia, New York Telephone Conversation. New York 2015, Photo: Simon Cave

Although written in 2010, not much has changed since Walter penned her book. Pandemonia’s anonymous creator riffs on this, subverting sexist stereotypes to criticise media, advertising and pretty much any money-making industry that cashes in by selling products off the female experience. “I chose the basest forms and virtues which are promoted to women through the media”, the anonymous artist who made Pandemonia says. “She had to be female because the female is the emblem of commercialism, and most products are sold using the female body – it’s the most effective advertising device known to mankind. By taking ownership of the female image, I’m reversing the dichotomy, from passive to critique.”

Where Pandemonia uses parody, artists like Jennifer Rubell and Josephine Meckseper use female mannequins to protest against the world’s richest industries monopolising femininity as ‘sellable’. In Meckseper’s Blow-Up (Michelli) (2014), women’s bodies are victims of whatever the political agenda of the time is, while Jennifer Rubell debases the vagina entirely, turning the crotch of a mannequin into a nutcracker in Nutcrackers (2012), creating a glib scene where women are reduced to nothing more than a function.

Mira Dancy, Call from Violet 2015, Installation view of Greater New York at MoMA PS1, 2015. © 2015 MoMA PS1; Photo Pablo Enriquez.

Both the artists Mira Dancy and Laurie Simmons ridicule the idea of a woman as an inanimate object. Dancy mimics the neon GIRLS GIRLS GIRLS signs outside strip clubs by making sex-positive female nude reliefs in neon. In her Love Doll series (2010-present), Simmons also manipulates the idea of inanimate female bodies by using a sex doll to explore what it means to be a woman in contemporary culture. “I really use them as subjects in a story I’ve been telling for a long time – a woman’s interior,” she says of the dolls. “How does a woman become a character, and what does that character mean?”

All of these artists object to hashtag feminism, and the cynical use of feminism by brands from Pepsi to H&M, to sell stuff to women that they probably don’t need. Retail mannequins offer telltale signs of the relationship between commerce and identity. They reflect the evolution of ‘trendy’ female body shapes, like the extreme female figures popular across the world for which young women wear ‘waist training’ corsets for years to attain.

Zoe Buckman, Every Curve 2015, Images courtesy of the Artist and Bethanie Brady Artist Management

Zoe Buckman, Every Curve 2015, Images courtesy of the Artist and Bethanie Brady Artist Management

The artists in Play With Me call bullshit on the effect advertising and media has had on women’s view of their bodies, and how these industries, though preaching feminism, are aimed at creating a need in the female “market”. London-born artist Zoe Buckman heavily criticises the commodification of female experience in all of her work, but in Every Curve (2015), she is militant. “I’ve wanted to make a large-scale public sculpture for a long time. In these sculptures, I’ve used text I’ve been gathering from film and television scripts that depict scenes of sexual violence against women,” she says of the multimedia piece which saw her sew misogynistic rap lyrics onto vintage underwear. “I find myself barely able to watch TV these days without growing furious at the same old plot lines and scenarios in which an (often young) female body is found dead while the male protagonists uncover all of her ‘dirty secrets’ to ascertain how she was raped and murdered.”

Consumers are so used to seeing airbrushed-into-abstraction images of women on social media―anyone who has seen a Facetuned Instagram picture will get the idea― that what we see in social media is becoming as unrealistic as what we see in advertising. Jeff Koons touched on this phenomenon in his 2013 ARTPOP album cover for Lady Gaga. The piece mimicked his Woman in Tub (1988) with a CGI-manipulated image of the singer posed in the same position. I’m not a fan of Jeff Koons’s presentation of women, but I think rather than objectifying Gaga he was spotlighting the unrealistic beauty standards in advertising, a climate in which women’s bodies are used to create feelings and urges with the ultimate aim of getting them to spend money.

Play With me: Dolls, Women, Art is out now, published by Laurence King Publishing.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.