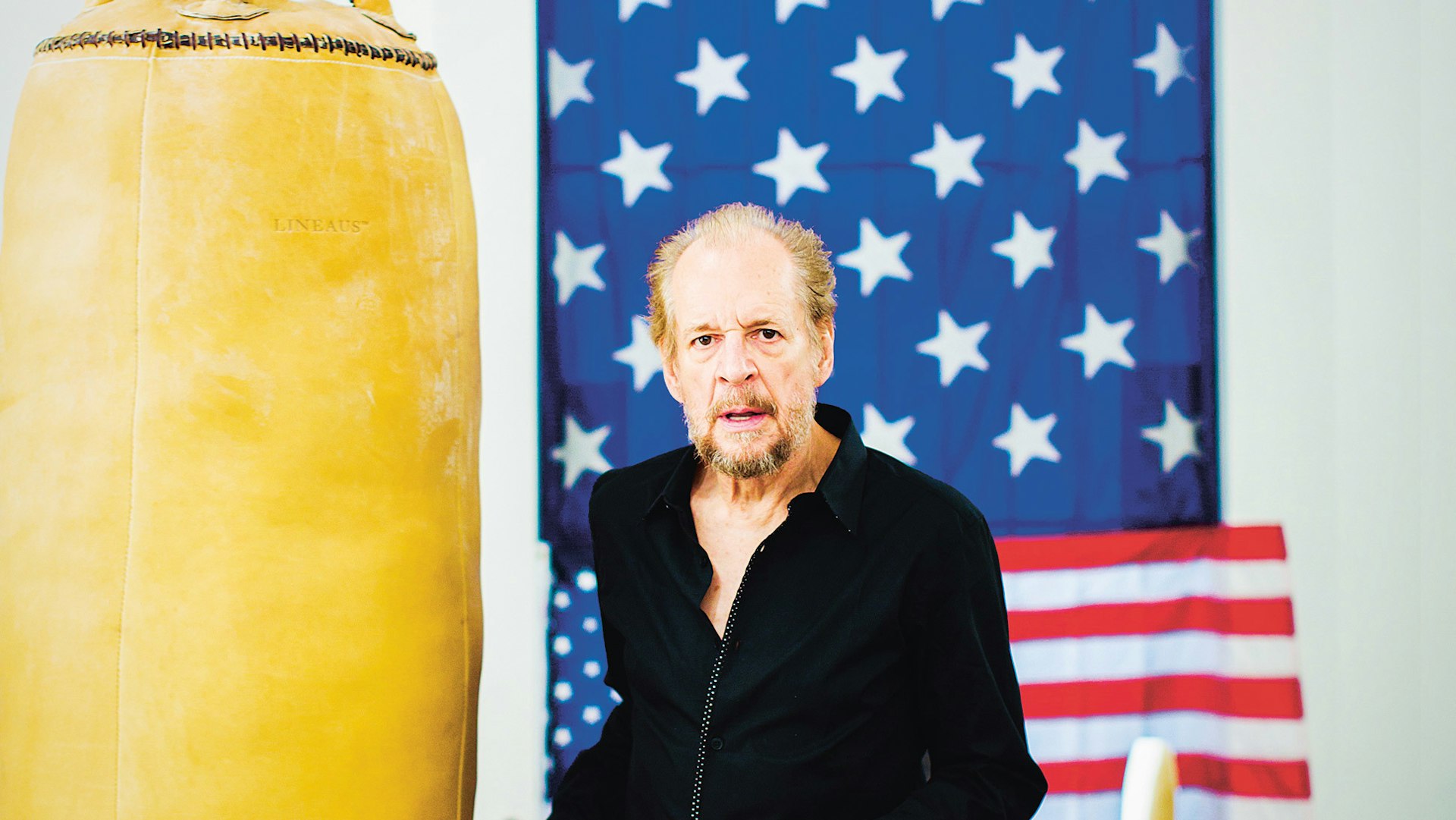

Jocko Weyland

- Text by Shelley Jones

- Photography by Grant Brittain

Jocko Weyland grew up in rural mountain Colorado during the late-1970s and early-1980s. Through skateboarding and punk rock, he found a way to sidestep general society and connect with a global community who shared his ride-or-die outlook on life. He’s worked in images his whole life – as an archivist for The Associated Press and photo researcher for magazines – and is passionate about drawing, painting, ‘zines, photography and writing, releasing a book The Answer Is Never: A Skateboarder’s History of the World in 2003.

His current ‘zine Elk is in its twenty-fifth issue and features everyone from Virginia Woolf to Pontus Alv. Jocko is currently in Lake Tahoe, on hiatus from New York City where he’s lived most of his adult life.

The Elk and The Skateboarder

An extract, by Jocko Weyland.

Open City, Issue #15.

“In 1981 Ronald Reagan was in office, there was a recession, unemployment was high, and the Cold War was at its height, filling my adolescent mind with hyper-realistic nightmares of nuclear annihilation. The popular culture I was exposed to was overwhelmingly boring, conservative and unwilling to address the ugly realities of life. Music was the domain of over-bloated rock bands whose time of innovation was twenty years past. It was grim. Skating was an outcast activity and it was becoming increasingly connected to the even more subversive and iconoclastic punk rock movement, particularly the brutally fast American offshoot of punk called hardcore. Punk rock then was actually a movement of substance and importance, not the watered-down artistically bankrupt genre it is today. It was new and scary and against everything that was the establishment. The music was alien — speeded up, aggressive, and genuinely strange. The lyrics dealt with things of real importance that weren’t talked about in the culture at large. What the bands were saying was edifying and I took them very seriously, imagining real changes and revolution. A whole world of radical politics and intellectual questioning that was completely absent in the discourse of the day was revealed to me. Skateboarding and punk rock changed my life.

[…] I started making my own [‘zine], Revenge Against Boredom, gluing and pasting pictures and doing all the writing myself. The first issue was three photocopied pages that grew to fourteen pages by the time I discontinued it after issue number five in 1984. I made 500 copies of it and sent it record stores and other ‘zine makers. My sister was living in Berlin so I got her to distribute there, people wrote from Yugoslavia and Australia for it, and I got a letter from Sonic Youth’s Thurston Moore that said, “Dear R.A.B., Please send me your ‘zine. I heard it’s cool.” It was a labour of love without any ulterior motives except to be a part of a community and trade information about the underground. It was fun, creative, and something to do instead of getting high and listening to Judas Priest.”

HUCK: Why did you start Elk?

Jocko: When I started making Elk in 2003 there wasn’t much going on with ‘zines. Certainly people were making them but it was kind of a low. In the last five years there’s been this real explosion. And now you’ve got things like the New York Art Book Fair and everything’s ‘zines, ‘zines, ‘zines. There’s been a sort of co-optation by the art world, or a willing collusion with the art world, and that didn’t really exist before the early 2000s. I worked in magazines, I was a photo researcher, but I wanted a magazine that didn’t exist, so I made it. And it was really mostly for myself. I wanted the image to stand on its own, and that’s what Elk is. Of course I didn’t invent that at all, Wyndham Lewis’ magazine Blast was doing that in the 1910s. And there were skate ‘zines that were really minimal, particularly one called Swank, which Tod Swank made, who is now the owner of TumYeto. There are others too. It’s just about the sequence of the photos and how they relate to each other without being overly explicit.

As you’ve gotten older, has the function of the ‘zine changed for you?

I don’t think making ‘zines is as exciting now for a lot of reasons, personally for me because they don’t have the same meaning. What made ‘zines feel so crucial, exciting, immediate and important, was growing up in a time when there was only mail. It was the only way of getting stuff. I also think there was a sort of golden age at that time, early-mid 1980s. It was untrained and unpremeditated. There’s still plenty of ‘zines I like, but there’s so many of them now and the people making them know what it means to make a ‘zine. You know what I mean? There are rules to go by. ‘Zines have become like a careerist thing. There’s a market for it. And back then it existed in a vacuum where money wasn’t even… it was just more inventive.

How do you choose what goes in Elk?

There are so many images out there in the world and it’s just about distilling it down to what I think is interesting. It’s funny in the internet age, the last ten years or something, a bunch of people have said, ‘Wow Elk, it’s like the internet but better.’ Or not better, but what’s not on the internet. In a strange way it has a relationship to how people search. It’s like a weird, analogue, three-dimensional extremely – and I’m not gonna use the word curated because I hate that word – but an extremely discriminating and subjective take on what’s out there. It’s also just sex, drugs, rock ‘n’ roll and architecture. That’s what usually ends up in it. Skateboarding is almost always in one of them. For a long time I was like, ‘I’m so sick of skateboarding I don’t want it in there. I don’t want everything to be about skateboarding.’ But it’s just impossible to erase that and I don’t want to erase that. That always shows up in some shape or form.

“I mean the great thing about skating is that it was not understood. Parents weren’t into their kids skating. It was this thing that nobody cared about.”

Are you still skating a lot?

I left New York a month and a half ago and I was skating pretty often there. It’s weird, I’ve talked to Mark [Gonzales] about this, but when we met there were no old skateboarders and I remember seeing Tony Alva when I was eighteen or something and being like, ‘Dude give it up! You’re way too old!’ And he was probably twenty-three. But now, I just saw this contest in New York back in September and Lance [Mountain] won the Masters or whatever and he’s better than ever. It’s odd to me but I feel lucky that my body can still do it.

It’s become institutionalised as a sport…

Oh totally, I totally think that. I mean there are much bigger problems in the world and at this point I really don’t care but this friend of mine, Rob Erickson, who has a long history in skateboarding, said to me, ‘I wish skateboarding would die so we could have it back.’ Skateboarding is so fucking gay now, and I don’t mean that in the homosexual way. It’s so gross and stupid on so many levels. I would never have imagined that and I don’t think anybody else did. But that’s what happened. It’s a huge business, of course it’s going to be full of idiocy. I mean the great thing about skating is that it was not understood. Parents weren’t into their kids skating. It was this thing that nobody cared about. And that’s what made it able to develop, or be really fun and interesting and cool, because it was happening outside of general society. But now it’s totally a part of general society, and that’s really taken a lot away from it. And what’s kind of depressing to me is this whole father and son at the skatepark thing. Not the dad skating, that’s one thing, but it’s become a regular sport; the dad’s hanging out like, ‘Make sure you get that rock and roll or you’re not gonna get dinner tonight!’

How long have you known Mark?

I met Mark when I was about eighteen, so probably 1985. I saw him skating at this contest in Huntington Beach, which was one of the first street skating contests. I guess everyone has said this before, but he was really noticeable. He was ollieing in a way nobody else was. Then we met a few times in San Diego. I remember riding a ramp with him and having a conversation about the poet Brion Gysin. I don’t remember how he knew him, or how I knew him. Then I didn’t see him for about five years and he turned up when I was living in New York and I saw him riding in Washington Square on this water-ski board he borrowed off a stoner buddy.

You’ve featured him in Elk. What do you like about his art?

I like Mark a lot, so I’m biased. His work is… organic, I guess is the word. It’s natural. It’s not thought out, not posed. His whole use of language is really funny and witty and interesting and kinda has some idiot-savant elegance. I think words and images often don’t work well in the context of drawing, unless you’re Raymond Pettibon or something. But Mark does this thing that’s kinda magical, like, we did a show together in Franklin Parrasch and he had this one piece, ‘The guy who has the food is the king of the zoo.’ And the way he says it or writes it is somehow revelatory. It makes you think about this totally mundane subject in a way you never have. ‘Oh yeah, the zoo! That’s funny!’

What are your plans for the future?

I probably won’t make another Elk for a while because I’m not living in New York anymore and I don’t have access to the photographs. But lately I’ve been painting these Russian doll figurines – just really rudimentary on gouache and watercolour paper. I’ve been learning how to paint, or trying to learn, just to try a new thing. Right now I’m really into Chaim Soutine. There’s a ton of stuff out there that’s interesting and cool.

Check out Mark Gonzales’ DIY video interview with Jocko, made exclusively for HUCK.