Rebecca Horn

- Text by Tetsuhiko Endo

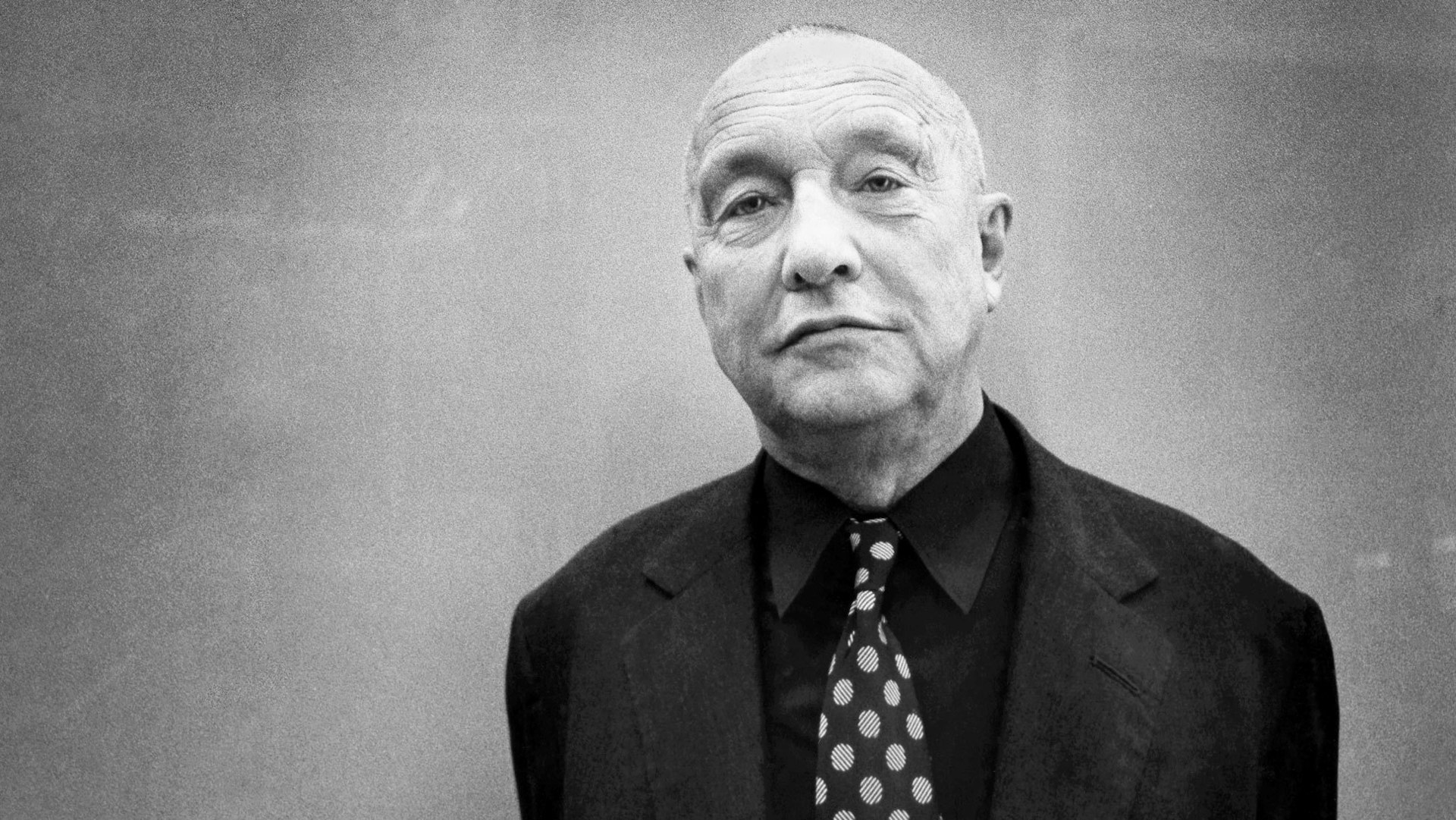

- Photography by Martine Franck / Magnum Photos

In the summer of 1926, Joseph Frank Keaton – better known as ‘Buster‘ – came to work in a small, Oregon mining town called Cottage Grove. With the help of a film crew, a closed section of railway, and a replica of an 1860s locomotive, he made film history. His feature-length silent comedy The General contains probably the finest chase scene to ever be committed to celluloid. In fact, the film is little more than one extended chase scene, a human Rube Goldberg device in which Keaton’s improbably athletic frame ping pongs around a moving locomotive like a live action cartoon.

Movement is the hardest art to capture and preserve. Keaton himself disdained the title of ‘artist‘. In some sense, it’s a matter of tangibility. The Mona Lisa, though over five-hundred years old, still sits in stately repose in the Louvre while large parts of the extensive repertory of the modern dancer Merce Cunningham died with him in 2009. “Evanescent,” “like water” – that’s how Cunningham described dance in his later years, as he turned to the daunting task of figuring out how to preserve what he could. He may as well have been talking about all movement, from Michael Jordan to Jackie Chan. You can see their performances again and again on in replica, but unless you were in the Delta Center for game five of the 1997 NBA finals, or on the set of Rumble in the Bronx, you have missed the original forever because it cannot be contained in a medium, just reproduced imperfectly.

The art of the kinetic is central to the work of German-born installation artist and filmmaker Rebecca Horn. Her work was once described in the Guardian (in an article tellingly titled ‘Bionic Woman’) as a cross between a performance and an installation because of her approach to portraying movement. She delights in creating both moving sculptures and body extensions that only come to life when attached to a human. One of the most famous examples of the latter is Horn’s ‘Finger Gloves’ – sinister yet somehow dainty rods of metal and fabric that, when attached to the hands, extend each finger some four feet. Although they now sit lifeless and inert at the Tate Modern in London, there is a 1974 video on YouTube of Horn wearing them while she slowly paces a rectangular room in Berlin, arms outstretched, ‘fingers’ rasping along the walls. It carries a mingled sense of elegance and menace, like a gothic horror film. The sound of the gloves on the wall echoes like slowly tearing paper while Horn paces the room in high heels, her hips moving languidly.

She is one of the few serious artists in the world willing to put herself in the same club as Chan and Johnny Knoxville, among others, by claiming Keaton as an inspiration. She even directed a film called Buster’s Bedroom, about a young woman who goes to the sanatorium where Keaton spent various stints for alcoholism and reenacts scenes linked to his life. Like many of her automata, the film is a sort of mystery box that one New York Times art critic described as having “a touch of Fellini’s magic, a touch of Visconti’s decadence and a touch of Bunuel’s liberating illogic” – surely the first and only time the names of those directors appear alongside those of a silent movie comedy star.

But these kinds of unexpected syntheses lie at the heart of Horn’s work. A mystic and a believer in alchemy, she captures the free floating potential of movement and breathes it into the inanimate, creating precise moments of art that drift away suddenly like the light of sparks in a dark room.

In a similar way, skateboarding distills movement in an almost desperate attempt to string together enough of these immaterial moments of action to form something wonderful, something defined by its very ephemerality. No one demonstrates that better than Mark Gonzales, who, along with Keaton, the patron saint of all grown men who bounce when they hit the ground, is a master of the uncut sequence. Watch any film clip that Gonz happens to pop up in – whether he’s rewriting skate history in Video Days (1991) or dancing down the street in a Spike Jonze short – and it’s immediately apparent that he favours long, unbroken lines, punctuated by the odd flourish. The camera follows him as he races through cities, often skitching on vehicles, neither moving towards nor away from anything. Sometimes it’s beautiful, sometimes comical, but you can’t help but get the feeling that the essence of the man, and what he’s striving for, is only truly apparent at speed.