The strength and struggle of black artists in America

- Text by Miss Rosen

The black arts movement swept through the United States in the ’60s and ’70s, bringing together artists who had been systematically excluded from the art world. Fueled by the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements of the era, black artists confronted issues of race, politics and identity while pushing the boundaries of creative expression into new and uncharted waters.

The work of pioneer African American gallerist Linda Goode Bryant was included in the landmark exhibition Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, currently on view at the de Young Museum in San Francisco. The exhibition showcased definitive works by artists of this era including Jack Whitten, Romare Bearden, Roy DeCarava, Ming Smith and Charles White, all of whom elevated the formal and conceptual possibilities of their respective mediums.

Bryant did the same for the gallery world, transforming the sterile white cube into a collective space for creativity, community, and conversation. In 1974, Bryant left her job at Education Director at the Studio Museum of Harlem to open Just Above Midtown (JAM) on 57 Street simply because she decided David Hammons absolutely had to show in New York, and he refused to exhibit at white galleries.

What she lacked in money, Brant made up for in knowledge and daring. “Art made me feel that I had the power to do anything despite what was happening around me, both in the community and the larger society,” she says.

Bryant set forth to find a location to show the work of black artists when few else would. “I showed up [at Judson Realty office] with a huge Angela Davis afro, two babies, and I was in army fatigues,” she remembers, with a laugh. “[Peter Marks, the broker] was in a state of shock.”

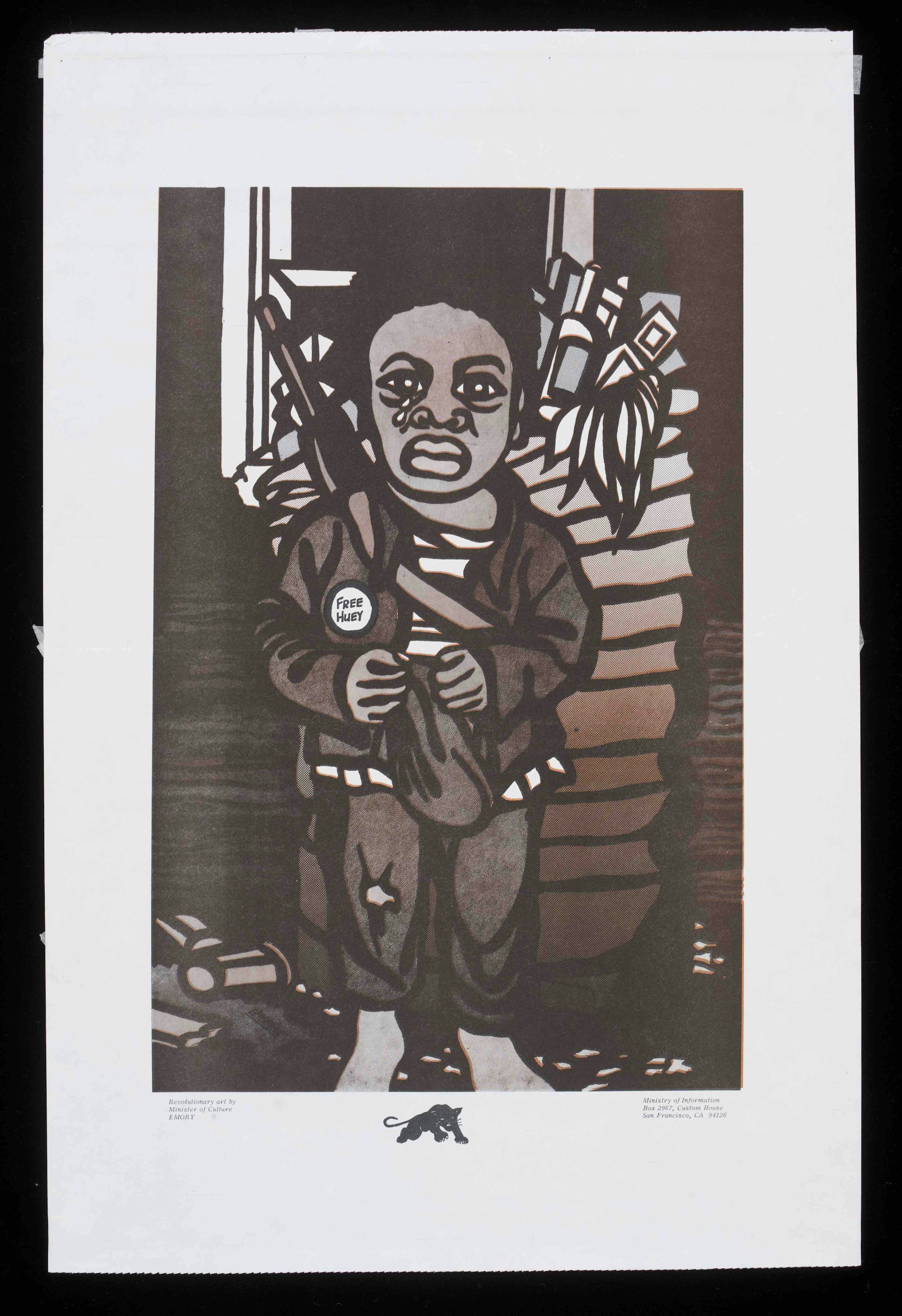

Poster Free Huey; Poster produced by the Black Panther Party during the “Free Huey” campaign, 1970 Emory Douglas United States 1970

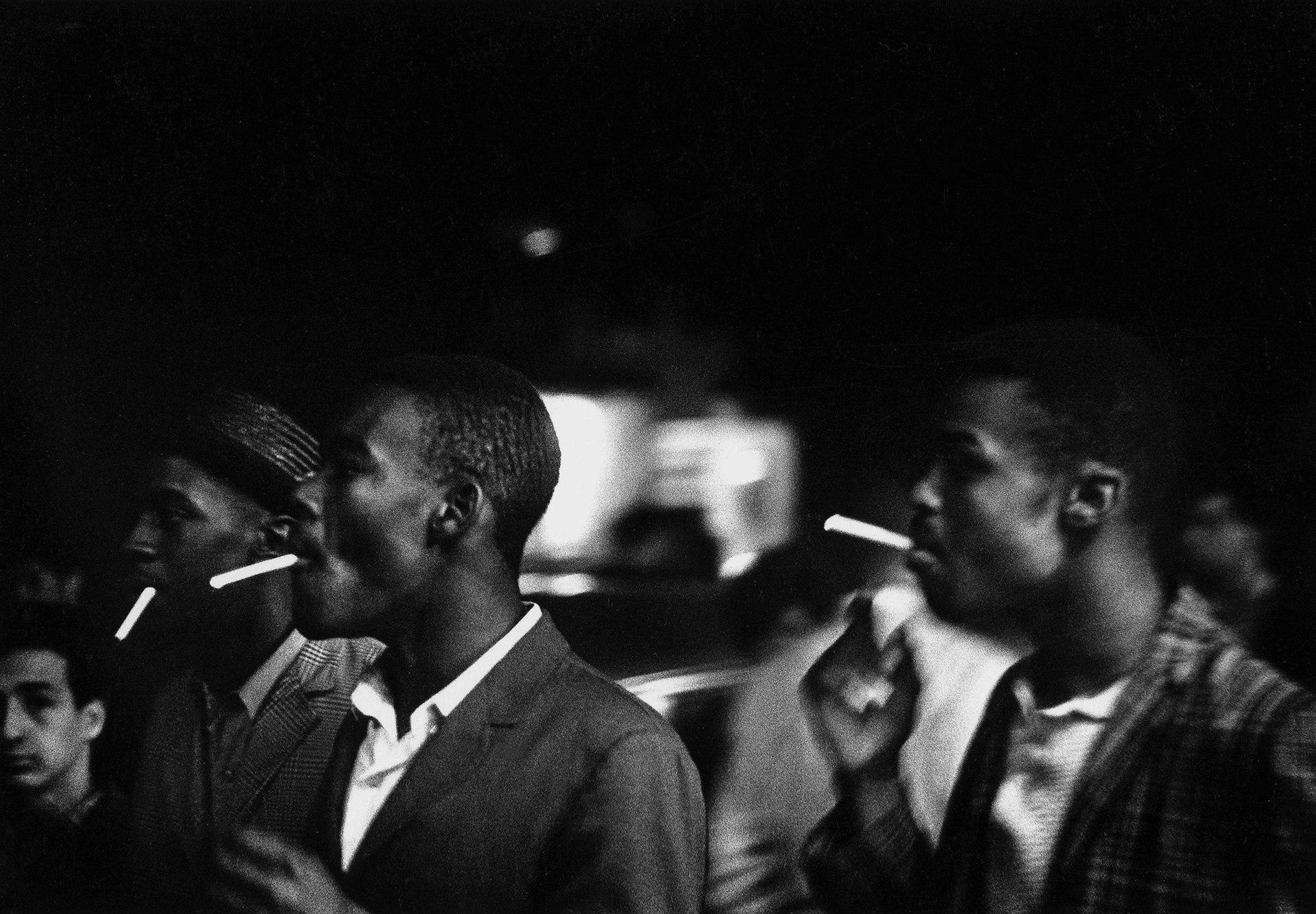

Al Fennar, “Rythmic Cigarettes, Greenwich Village, New York” 1964 © The Estate of Albert R. Fennar Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

“I asked how much the rent was and he said, ‘$1,000 a month.’ I just looked at him incredulously and I said, ‘I can’t pay that.’ He said, ‘How much can you pay? I said, ‘$300 a month’ – and mind you I didn’t have a dime.”

Needless to say, Bryant got herself a deal and began showing groundbreaking black artists at the start of their career, including Adrian Piper, Howardina Pindell, Maren Hassinger, Ming Smith and Elizabeth Catlett. For Bryant, JAM was more than a commercial space – it was a work of art itself.

Bryant designed the 725-square foot space to provide artists with innovative opportunities, finding new ways to support and help take them to the next level of their work. At the same time, she understood the realities of the industry, and worked to create a community of collectors who played a significant role in helping new artists establish their careers.

“We did this series, Brunch with JAM, which was for the community of 57,” she says. “For $5 you could come to JAM, get lunch that a friend prepared, and a lecture from a curator, critic, artist or collector, and we’d sell out each brunch. The art world was boggled by it.”

“I would be grilled by my colleague: ‘How can you call barbecue bones and grease art? Hours of having to talk to people and talk them through the elements of a piece because it rankled what they knew.”

Benny Andrews (1930–2006), “Did the Bear Sit Under a Tree?” 1969 © Estate of Benny Andrews / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy Michael Rosenfeld Gallery, LLC, New York, NY Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Barbara Jones-Hogu (born 1938) “Unite”, 1971 Screenprint Estate of Barbara Jones-Hogu, Courtesy of Lusenhop Fine Art image provided courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

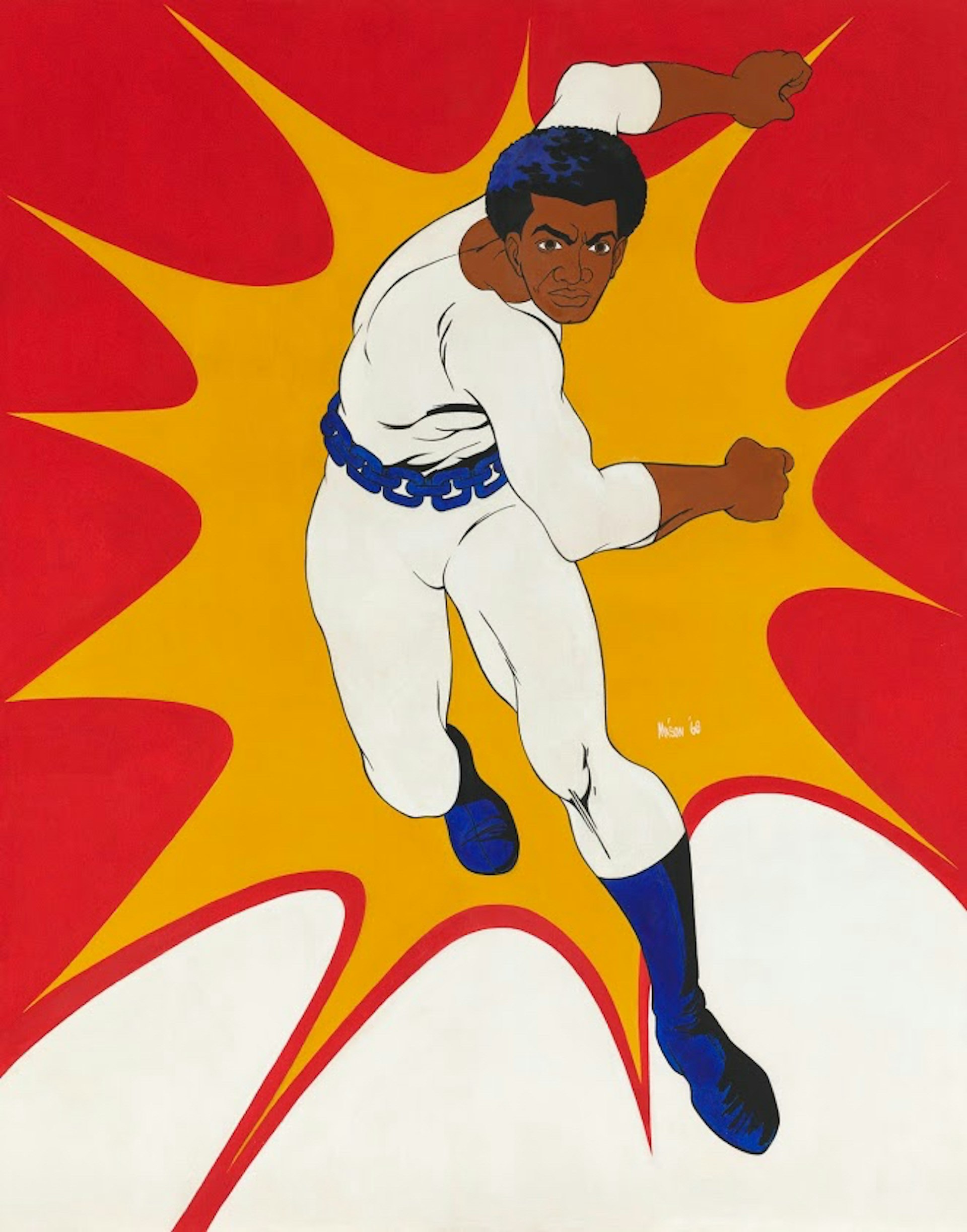

Phillip Lindsay Mason (United States, 1939 – ) “The Hero”, ca. 1979 Mills College Art Museum © Phillip Lindsay Mason Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Norman Lewis (1909 – 1979) “America the Beautiful”, 1960 © Estate of Norman Lewis; Courtesy of Michael Rosenfeld Gallery LLC, New York, NY Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

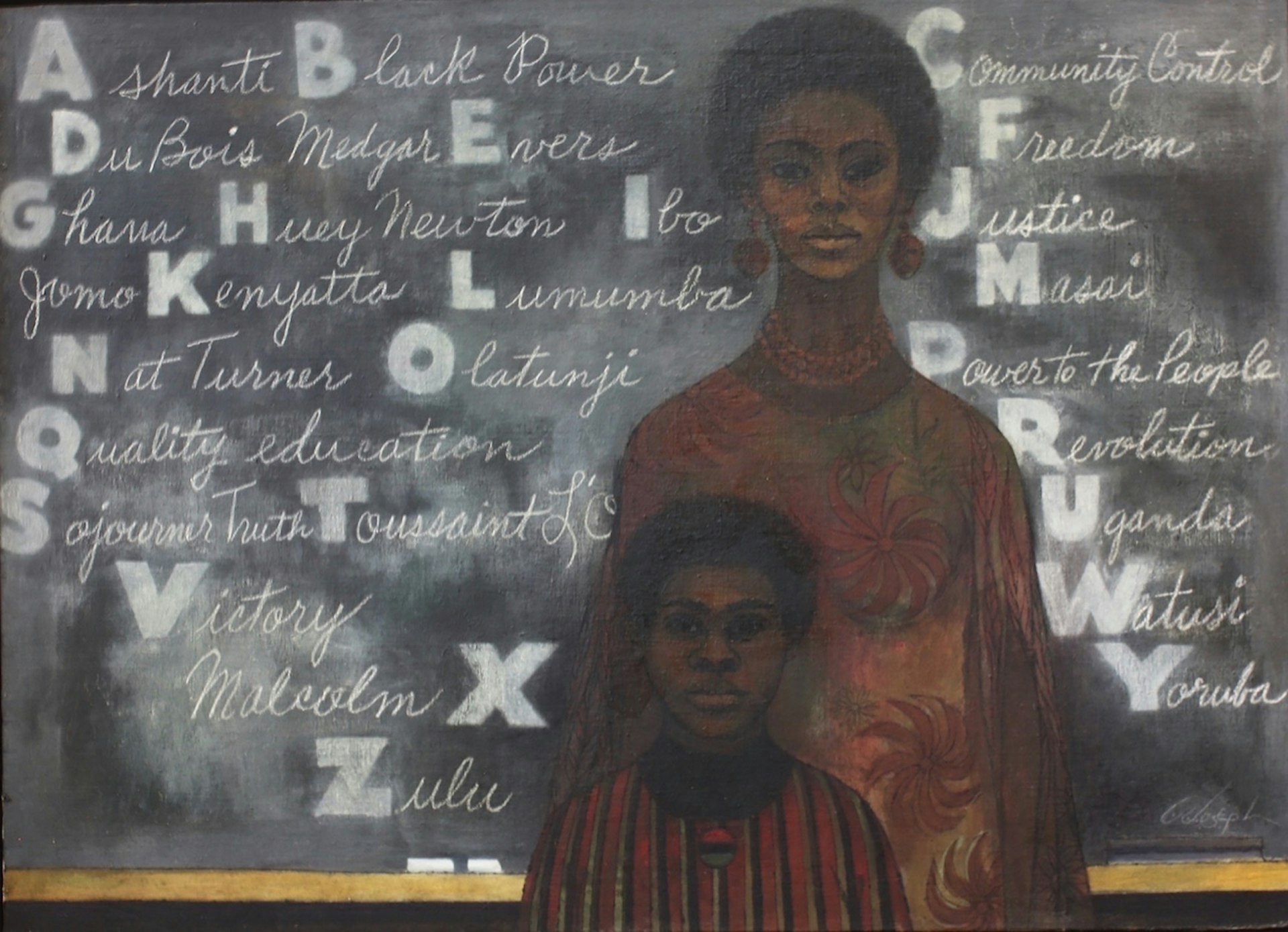

Cliff Joseph (born 1922) “Blackboard”, 1969 AARON GALLERIES, Glenview, Illinois Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Phillip Lindsay Mason (United States, 1939 – ) “The Hero”, ca. 1979 Mills College Art Museum © Phillip Lindsay Mason Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Barkley L. Hendricks “What’s Going On”, 1974 Courtesy of the artist’s estate and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.” Image courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power 1963-1983 is on view at the de Young Museum in San Francisco until March 15, 2020.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.