Inside the Favelas

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Douglas Mayhew

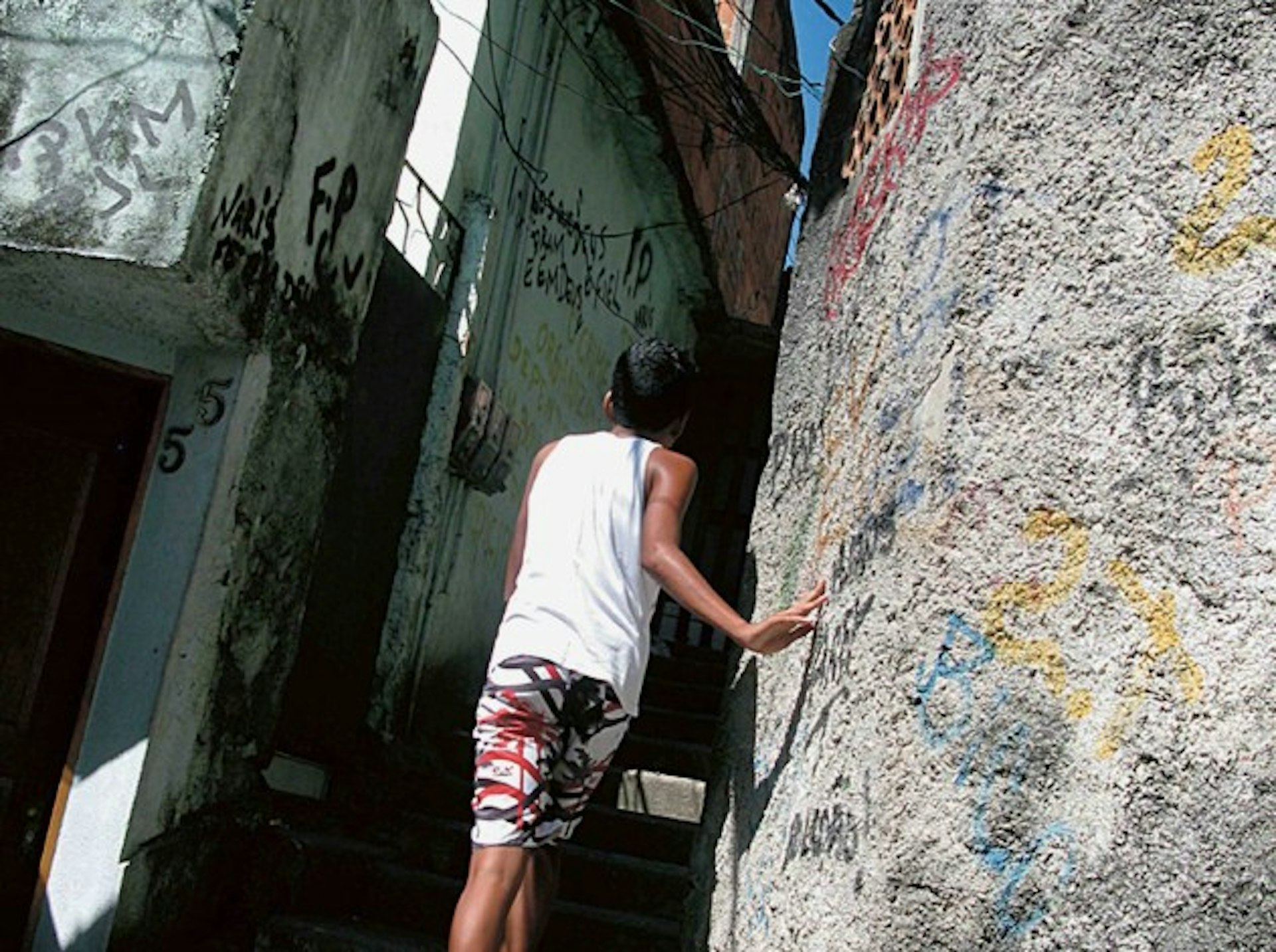

During television coverage of the World Cup in Brazil, sanitised versions of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas appeared in glossy idents or as colourful wallpaper for TV broadcasts around the world. But for those wanting a less superficial insight into these labyrinthine communities bursting with cultural invention – yet often blighted by shocking levels of violence – Inside the Favelas: Rio de Janeiro by Douglas Mayhew is a great place to start.

As an artist from Detroit, Douglas is no stranger to tough urban environments but the favelas of Rio make the Motor City look like Toy Town. Although many of the city’s most notorious favelas have now been successfully “pacified” in a government campaign to bring in social services alongside the re-establishment of police control, they remain highly complicated places and many feel the underlying the issues have not yet been tackled. In unpacified areas the drug traffickers are still in control and maintain order with ever-changing un-written rules and automatic weapons.

After moving to Rio, Douglas was mystified by these seemingly impenetrable communities but wound up being granted entry by the traffickers once he explained his project to them. Shooting from the hip to remain as inconspicuous as possible, the artist meets guerrilla photo-anthropologist spent years photographing – but also listening, watching and learning – to produce his exhaustive and thoughtful documentation of favela life.

Huck spoke to Douglas to learn more about the project.

What first attracted you to document favela life?

I volunteer in the recreation room on a children’s ward at a large public hospital in Rio. On Mondays, I open the recreation room and the cabinets of toys, and walk through the ward letting parents and kids know that the room is open, and I play games and make puzzles with the children who come.

Six years ago, a boy came in with a severely infected, deep wound. The cause was a gunshot at close range. The child had been purposefully shot on orders from the favela’s top narcotics trafficker to punish his parents; they had broken a rule, I was told, of the favela where they lived. The boy had been denied medical attention for ten days for the same reason. My confusion was evident.

I was advised by a colleague to ignore the situation because it happened all the time. She said since I was new to Rio, I didn’t know about the traffickers’ policies and how they controlled the lives of the residents and that I should get accustomed to “their” way of life. I didn’t.

I began to understand that, for whatever reason, the life of this child was in danger and not just because of the bullet but because of the environment in which he lived. Two weeks later, I found a way to cross the favela/non-favela line and discover for myself what no one would talk about or explain to me.

I think I was also attracted to the favelas because I grew up in Detroit during the civil rights era. What I saw and experienced changed my world. It was a tumultuous time and the more I learned about the favelas, the more I remembered how carelessly Detroit’s politicians cared for its poor and jobless citizens.

In hindsight, the reason I began visiting the favelas wasn’t the reason that ultimately made me create a book. The favelas are essentially off limits physically and emotionally to the people who live in Rio but don’t live in the favelas; too much history and heavy baggage for them – but not for me.

As the final edits approached, I realised I wrote the book in part to wake people up and to strip away the visual wallpaper that the hillside favelas had become to so many who were unaware of the hardships that existed inside the favelas.

Did you feel a responsibility to the communities you shot in?

My responsibility is to stay the course and shepherd the projects that grow out of my work to a meaningful conclusion. I promised the people I met that I would tell their stories with compassion, honesty, and respect, and to return with copies of the book once it was published.

In so many cases, the residents of one favela have never been to other favelas and with the book on their laps they can ask me questions, see the similarities and differences, and begin to understand that they are not alone. In these moments my responsibility is to listen.

For non-residents, the photographs illustrate an arena of ideas that are threatening and most people focus on the artistic merits of the shots in order to avoid thinking about the obvious. In these moments, I get people talking about the problems faced by the underprivileged from the standpoint of an artist and not from the perspective of a photojournalist.

Though difficult given the subject and the environment where I work, I try to ensure that my work does not contribute to the fetishizing of violence that is so prevalent in today’s media. A shot of an empty schoolroom conveys more than one of a kid holding a rifle.

What were the challenges of shooting in such a complex environment?

It’s very tough to pare down the difficulties of shooting in the favelas to a manageable bundle. A Chinese menu approach runs short on dishes, the analogy of a corporate organisational chart would have too many arrows, and an old-fashion grocery list of dangers would be too long. The problem is that pigeonholes lack the power to describe the mental and physical challenges I face when I’m at work and the emotional consequences of my experiences when I’m home.

Three powerful criminal organisations control Rio’s favelas and the lives of residents. Their business is drug trafficking and arms dealing and their operational methods are unimaginably brutal and merciless. Working with their military-styled personnel is very rough. Six years in and every day I still face new sets of rules, regulations, and punishments dictated by the quixotic and paranoid behaviours of the drug gangs.

Supra-communication systems don’t exist and operational procedures are not codified. There aren’t coordinated strategies except at the highest levels; day-to-day business is controlled on-site. There are no visitor visas or press passes because a gang’s permission to enter a favela in the past is useless in the present. One ramification of their spur-of-the-moment way of doing things is that each time I visit or revisit a favela I’m forced to explain who I am, why I’m there, what I would like to do and, why am I doing it. Each time it’s either thumbs up or down regarding whether the boss will allow me to enter his territory and walk around.

I am usually asked the same questions by residents and I might be interrogated by soldiers on post or by roving gangs who want to know who authorised my presence; a machine gun in my stomach or a pistol to my head is sometimes a part of the process. In these situations, a careful balance between subservience and confidence is necessary – being honest is an imperative. Afterward, if the same guys offer me a beer I accept and don’t think about the surreal nature of the circumstances.

Requests to take photos are just that – requests. It usually starts a firestorm of dissent and accusations that I’m not who I say I am; the outcome is never a certainty. The subjects that interest me, architecture and public spaces I always say, doesn’t mean anything to them so most of the time I’m allowed to take photos, within strict parameters that they make very clear. Photo reviews on the way out happen eighty percent of the time.

I carry a rugged Canon PowerShot G1 X covered in black electrical tape for fieldwork and I shoot from the hip which means I both wing it and I take every shot from waist level. Long lenses are out and I never raise the camera to my eye; it draws too much attention. I wear cargo pants with big pockets on every trip and I never carry my camera openly unless shooting. Exigent circumstances mean I can’t compose shots and that dovetails well with my belief that abstraction tells the truth.

What did you learn while making the book?

I’m a trekker. I climb tough terrain in both work and life. I like the singularity of the sport and I like how it makes me feel. Climbing was there during the genesis of the project and throughout the idea’s development.

In order to realise the goals of the book, I had to break out of my climbing mode and assemble a team of committed professionals who believed in me first and the project second. I made missteps along the way that in a favela would have meant bad falls and broken bones and I placed my trust in great meetings/bad follow-through types, a few too many times.

After wasting a lot of time and cash, I was very lucky to find the right mix – a seasoned design team for the visual concept and layout, a copy editor that took control of untamed paragraphs, smart, experienced printers who focused on solid production methods and top-quality materials, and above all, a publisher who didn’t let me quit when, as creative people know, you want to quit. When you’re producing an art book you can’t go it alone.

Once all the cost estimates were readjusted upwards, all the hard drives had finished crashing, and the corrupted bar codes had been fixed, the real hard knocks started raining down: dock strikes, customs seizures, philosophical transport agents, and hardest of all, the moment you’re told to stop creating and recreating and go to the beach and have glass of wine. And then the other shoe drops – your team tells you, in a humorous way, that the file had been closed the day before.

What I learned from it all was to let go of my ego, begin the next project before the last one is finished, and to let the work of art, or presentation, or novel, or symphony be born and learn to walk on its own.

Find out more about Douglas Mayhew’s awesome Inside the Favelas: Rio de Janeiro, published by Glitterati Incorporated.