The cult comic rewriting the history of female sexuality

- Text by Ione Gamble

- Photography by Liv Strömquist / Little, Brown

Sugar, spice and all things nice — that’s what we’re told growing up that girls are made of. But while rhyming couplets and long division may be hammered into the national curriculum, two vital schools of learning are missing completely; the history of the female reproductive system, and femme sexuality.

One woman aiming to rewrite the history books is comics artist Liv Strömquist. Reaching adulthood in Sweden during the height of Riot Grrrl, Strömquist first took pen to paper as a creative approach to addressing gender inequality and has been working to educate women ever since. Her work – which ranges from illustrations for national newspapers, to printing out zines to distribute amongst friends – has been translated into over a dozen languages.

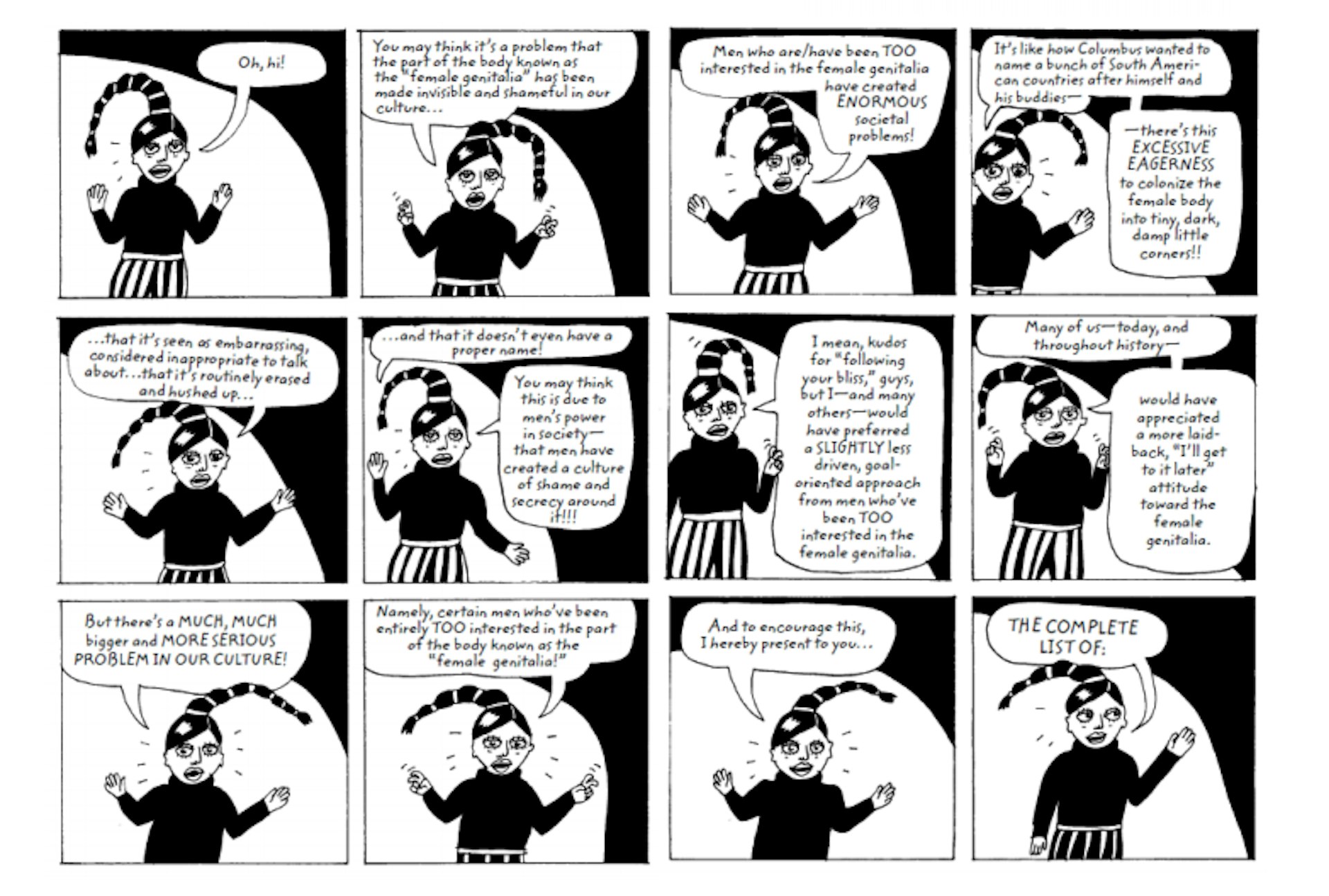

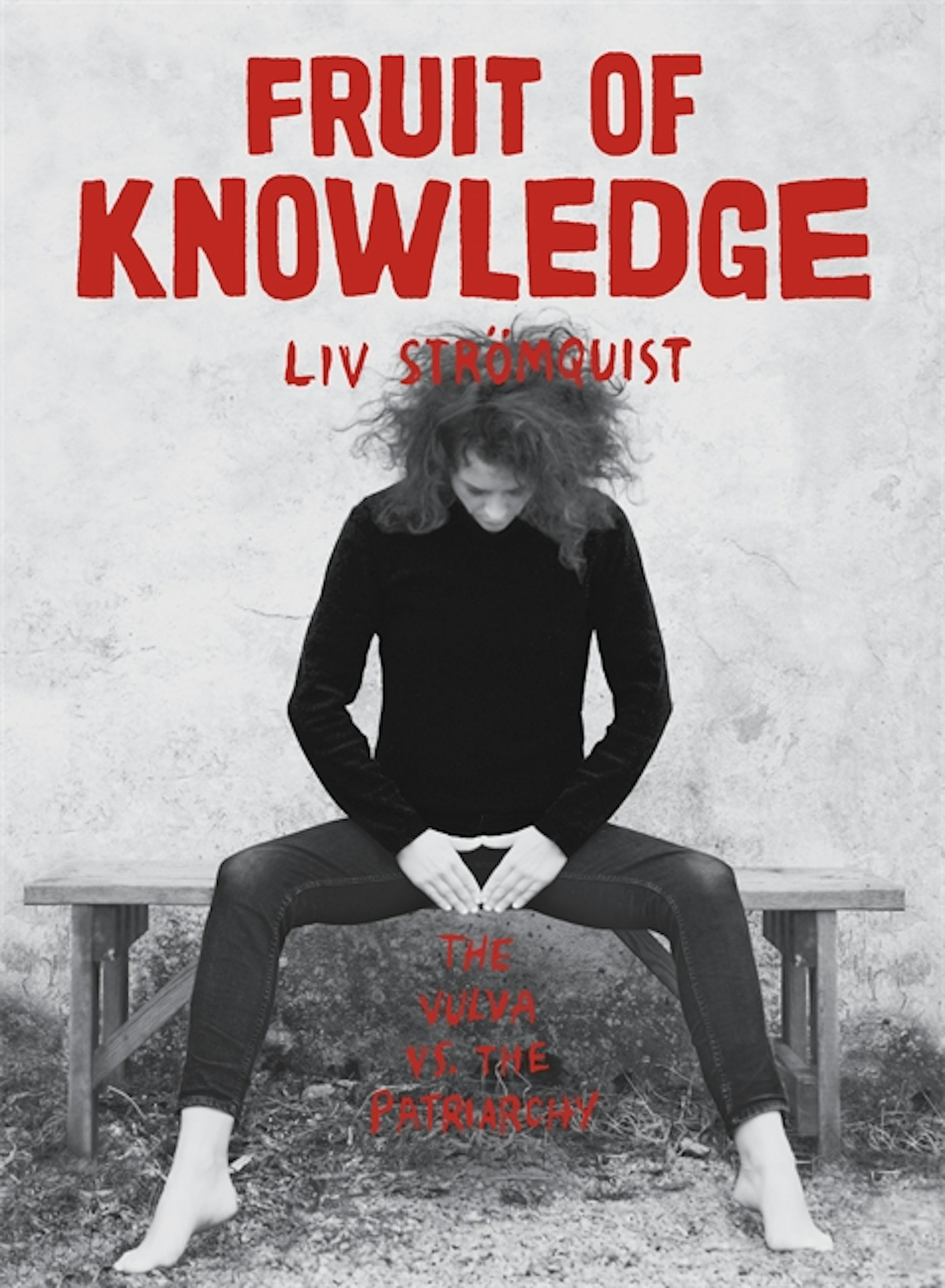

With her book Fruit of Knowledge, Strömquist takes a satirical approach to the ins and outs of the female experience, dispelling the harmful, misogynist myths that keep women feeling ashamed of their bodies and sexualities. And this year, the first English translation of Fruit of Knowledge finally hit our shelves. We caught up with the artist to discuss vulvas, fanzines, and what it’ll really take to alter societies backwards perspectives on women and our sex drives.

Why did you go for comics as your chosen medium?

I was making comics as a kid, because i really liked to draw and was also writing texts on my drawings. I was never a comic nerd as a child. My main interest when I was younger was writing fiction, but I always felt like I wasn’t good enough.

Comics, on the other hand, were something that I knew almost nothing about. I didn’t know any comic artists or what was considered to be good or bad in terms of comics. In that world, there are exactly the same ideas about what is considered to be a high-quality comic – but fortunately, I knew nothing about that.

You mention zine culture as an influence on your work – when did you first encounter it?

When I was 25 I had a flatmate who made her own zines, and I thought that it looked like a lot of fun so I made my own comic fanzine. The creativity came to me really easily, because there was no pressure. It’s not high brow culture, it’s more popular culture. I was very inspired by the DIY movement and the Riot Grrrls and Kathleen Hanna, I listened a lot to Bikini Kill and other feminist punk music which really inspired me, then I found out they made their own zines.

I made about 20 copies and my friend and I threw a party in my apartment and sold them for one euro a piece. I thought that would be the end of it. But then, for some reason, I discovered quite quickly that my comics had some sort of appeal for people. I remember visiting a neighbouring town and finding out that someone there had made a copy of my comic and put it up in the street as a poster. Then a newspaper got their hands on it and asked if I wanted to start drawing for them, so I started doing that. Then I published my own book and the demand was constant. After a few years, I just realised I was a comic artist — it wasn’t even a choice.

Do you think people’s attitudes towards female sexuality have changed at all since the beginning of your career?

If you go to a school playground and see a girl who is really experimenting with her sexuality or doing things for her own pleasure, she is still called a slut. I don’t think that’s changed very much. She still can’t brag in the same way men can about having slept with a lot of girls. I would be very surprised if there was a big difference there.

The force of capitalism is something that really influences this. I can see that we are constantly sexualising the female body – maybe even more now than before because of social media. This whole culture is based on imagery of the female body. You can see the obsession with looks and with wanting to be a sexually desirable object is even stronger than when I was a teenager. I can’t imagine what it’s like to be 13 or 14 and be exposed to all these images all the time, I think it’s harsher in some ways.

As someone who has always dealt with politics within their work, how do you feel about the commodification of feminism we’re currently seeing in popular culture?

I don’t know if feminism can be saved, maybe we have to abandon it. We’ve seen these developments that makes feminism completely harmless – it’s no longer questioning anything, it’s just embracing the same power structures we’ve had before. They just want to see women in the same position as men, and we’re just upholding the same capitalist structure. It’s the constant capitalist logic; embrace any counterculture and make it a part of capitalism. This began a decade ago maybe – it’s not just happening now. It’s been happening for a long time and is really important to address.

What’s one thing we can all do to lessen the stigma surrounding female sexuality?

For me, it was really interesting and empowering to just get to know more things about the cultural history of the vulva. Learning about these things and their history is something that I felt was very positive for me. It’s a part of our history, but you don’t know anything about it. In school, you would never learn anything about the history of menstruation. I remember really wondering about these things – what did they do when they didn’t have tampons? How have perceptions of menstruation changed in society? What was really motivating me when making the book was that I was so curious about all of these things, and it was really healing in a way to get all of this knowledge about it.

Interview has been edited and condensed for length. Fruit of Knowledge is available now on Little, Brown.

Follow Ione Gamble on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.