A brief history of the British tattoo

- Text by Michael Segalov

A tattooist once said to art historian Matt Lodder that while it’s all well and good to be an art historian, researching paintings and the history of sculptures, to understand the history of a nation you need to understand the history of its tattoos. What we mark on us is what resonates; the images, words and symbols that a generation forever stamps onto its skin.

In a new exhibition at The National Maritime Museum in Cornwall Matt Lodder does exactly that. “I’m an academic and art historian, and have been working on tattooing history for quite along time,” Matt tells me. “One of the things that has always frustrated me is that tattooing is constantly portrayed as a new ‘thing’, as if there was some kind of mythical beforehand when tattoos were just for criminals or sailors.”

In his research Matt has collected examples of that cliché from every decade from the 1870s onwards; it turns out tattoos have long been an important part of British culture and history. Our generation isn’t responsible making them the new big thing. Think back a little longer though, and no doubt you’d point to criminal gangs as the starting point for all think ink, but Matt says this too is simply wrong.

“The relationship between tattooing and criminality comes largely from Italian and French criminologists,” Matt explains. “It’s linked into broader intellectual movements of scientific racism and eugenics.” The idea that you can tell something about the character of an individual from their bodies was all the rage in the 19th century, and Cesare Lombroso, an Italian criminologist, even inspired Austrian cultural commentator Adolf Loos in 1908 to assert:

“People with tattoos who are not in prison are either latent criminals or degenerate aristocrats. If a tattooed man dies at liberty, he has simply died some years before he has been able to commit a murder.”

It’s a falsity that Matt has been keen to dispel. “Sure, lots of tattooed people were in prison, but no comparable evidence was produced from the wider population,” he says. If you’re a historian looking for evidence of tattoos in history, you’ll look on official records. Normal people just don’t have their bodies recorded in the same way as criminals.” This link is just an artefact of the historical record, not an artefact of history itself.

But if tattoos aren’t a modern fad, and didn’t spawn from the British criminal underworld, then where does our rich heritage of inking come from?

“What we wanted to do with the exhibition was to lay out a chronology in order to show there’s no before and after, there’s growth, development and change,” Matt continues. “There was no time when tattoos were for just one type of person.” Tattoos are the longest sustained trend in history, according to Matt, and this is how it all began.

Religious Beginnings

“We start with 17th century and antiquarian ideas of Britain’s past. In the 17th century colonial exporters start bringing back tattooed ‘natives’ from the East Indies and the Americas. In fact, they were put on public display as early as the 1500s.

“But it was in the 17th century that we see this better documented. A captive was literally exhibited in a pub, as a human curiosity. British antiquarians compared these tattoos with those the Roman’s had written about on accent Britons. These scholars would write about people needn’t worry about ‘savages’, as our own ancestors were just the same, like there was an embedded history. But the modern tattoo trade in Britain – with tattoos as commodities – began in the late 17th century with pilgrims.

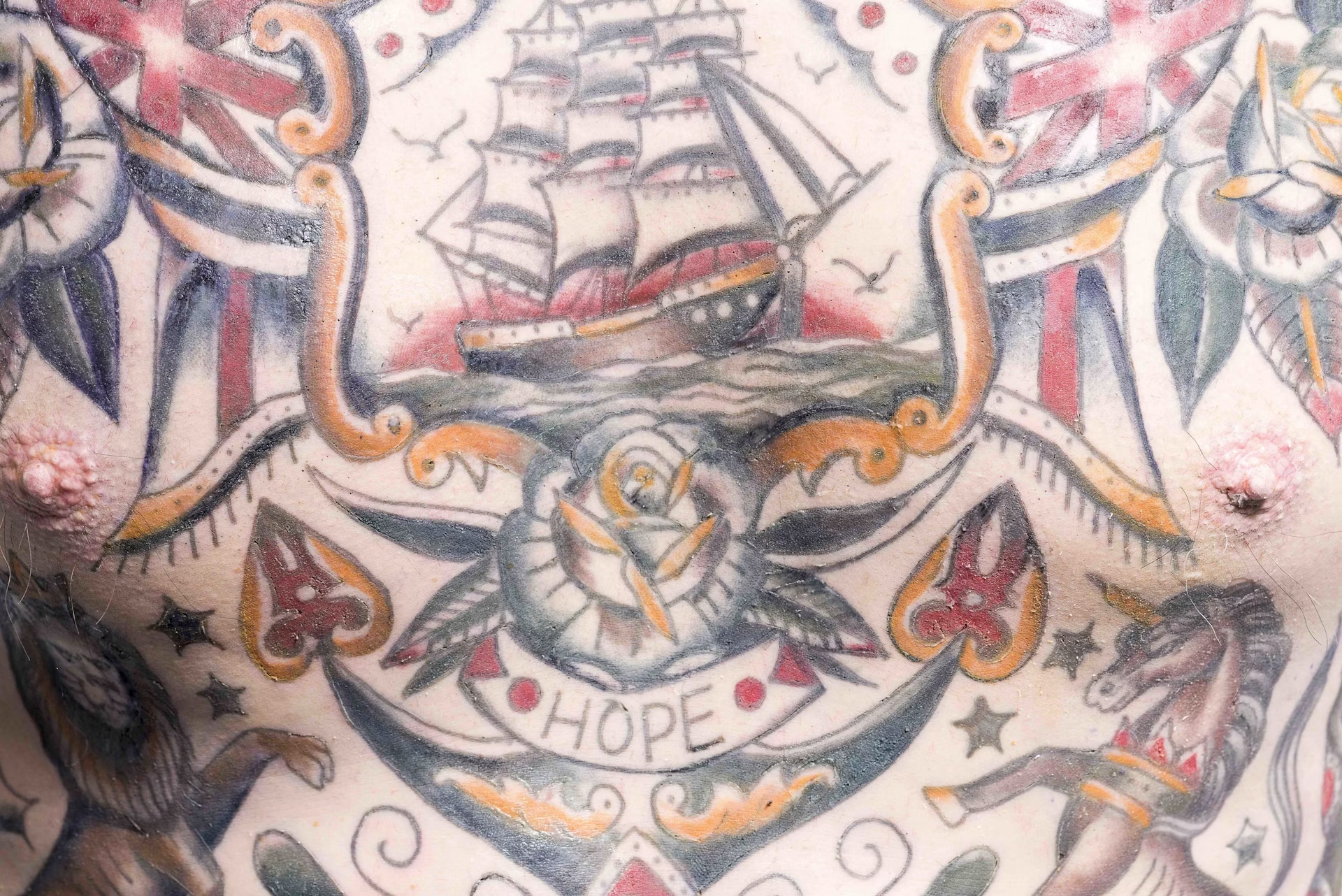

“Wealthy people – mostly men – would travel to Bethlehem, Jerusalem and Nazareth and get tattoos when they were there. Often very extensively, like footballers today, with lots of crosses and religious iconography. Essentially designs were carved into wooded blocks, and then printed onto the skin by dipping the block into ink. Then tattooists would use a single needle and puncture by hand with blank ink into the skin. It’s a slow process, but similar to the hand poke artists today.

“There’s lots of theological debate about whether tattooing is prohibited in religion, but even in Islamic cultures there’s an embedded tattoo culture. It’s Christianity that forms the basis of the western tattoo tradition.

The Captain Cook Myth

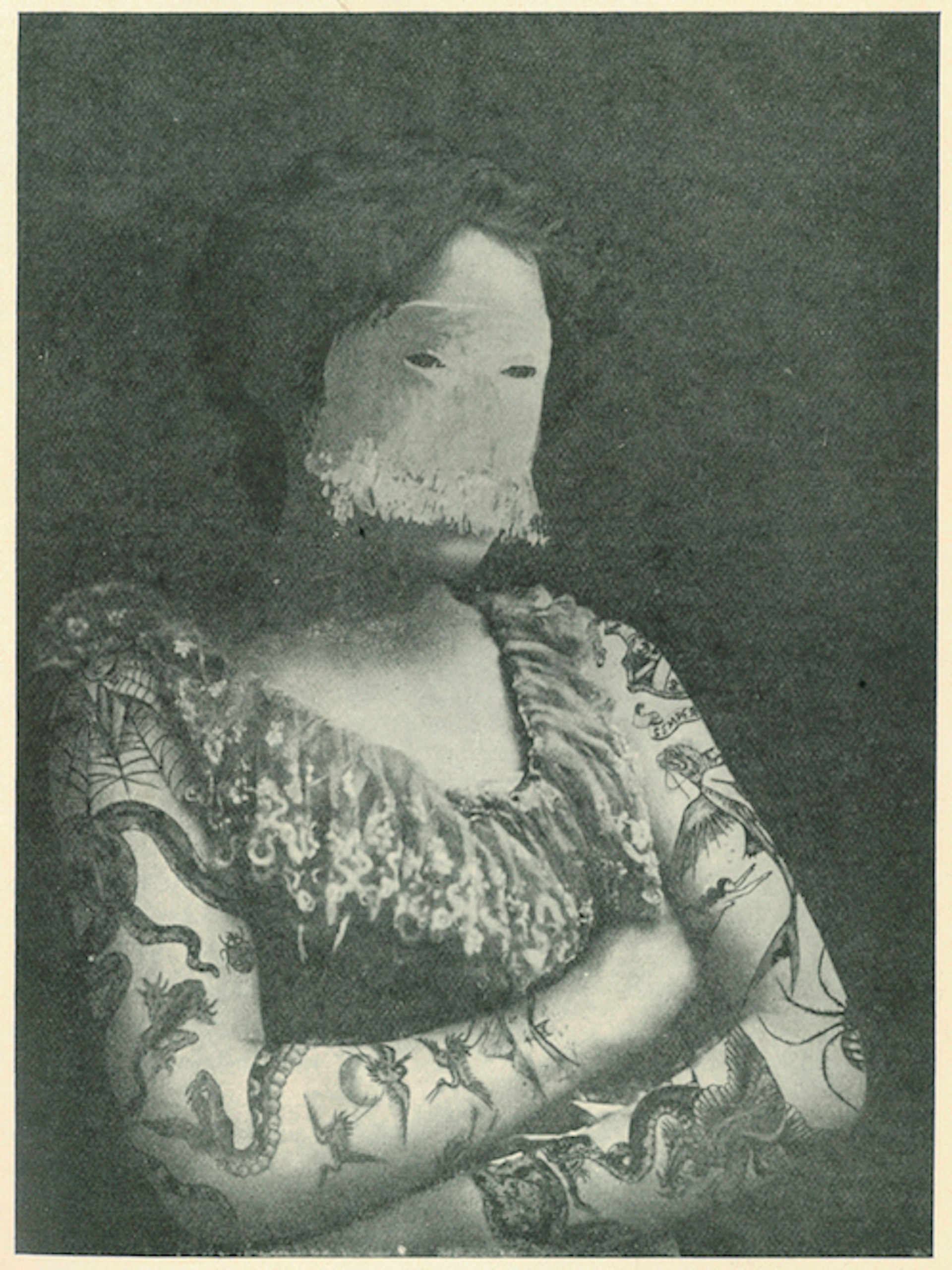

“Next we move into the 18th century (1700s). The standard story was that Captain Cook in the 1790s discovered tattooing in Tahiti and New Zealand and bought it back to the UK, as if it was an imported practice. But we’ve found images of a tattooed lady from 1740s, a criminal from the 1730s. Even before Cook set sail there are tattoos in Britain. We do tell the story of Cook’s voyages, it marks the moment – if not a rise in popularity – of at least when it enters the historical record because from then the navy kept track of tattoos.

“On your enlistment records the navy would have a column in the record book which lists what sort of designs you had, where on the body, sometimes the tattoo would be drawn or sketched. There’s even a painting in the House of Lords – The Death of Nelson – featuring all these tattooed men sacrificing their lives for the nation. It puts tattooed men at the centre of British life and history.

The inked up 19th century

“In 1868 Japan is opened up to the west, until then it had been closed to western trade for centuries. Now a new government was taking over, and the west was flooded with all things Japanese. From ceramics to prints, and textiles to tattooing. Wealthy travellers would go to Japan, and the same shops that would sell tourist isouveriners would now have in house tattooists. The wealthy clientele would head back too Europe or America with tattoos, and their friends would want them too.

“In 1871 there was a famous case in the tabloids all across Victorian London about Roger Tichborne – an aristocrat lost at sea – turned up alive many years later.

“His siblings were suspicious as he appeared to have put on lots of weight, and seemingly had selective amnesia. The thing is, he stood to inherit the family fortune, so the siblings took him to court. It turned out that this aristocrat, Tichborne, had been tattooed, but this imposter didn’t have one. It turned out he was in fact a butcher’s son from Wapping.

“The first tattoo artist opened up a space in a Turkish baths in the late 1880s in Jermyn Street, London, then the height of the fashionable West End. It means that from then it was possible to make a living. Where does the professional industry begin? At the upper class of British society.

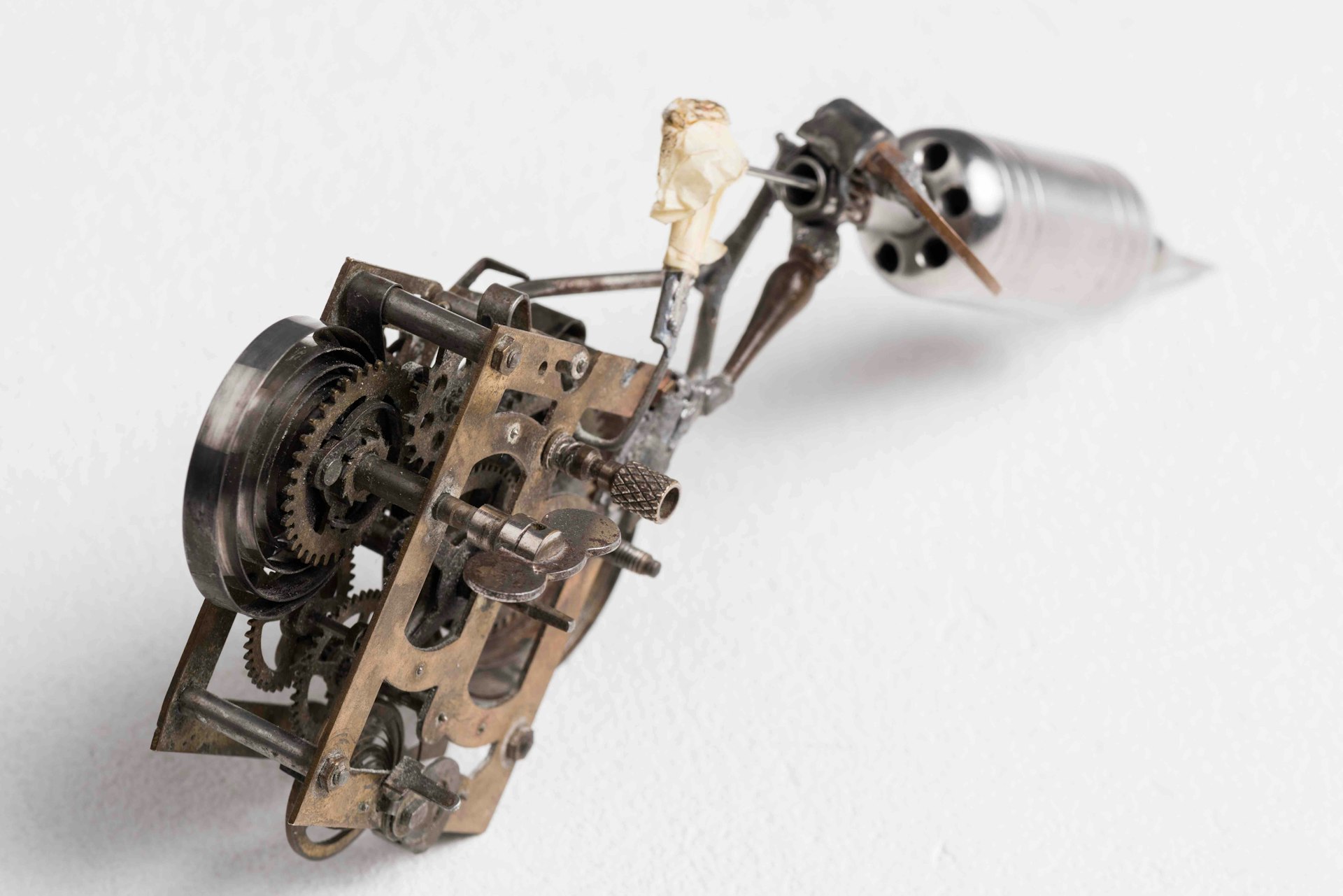

“Sutherland MacDonald was the first professional tattoo artist in Britain, and developed the first tattoo machine. He became the patent holder of an electric tattoo machine. And the thing is, with electrification comes speedier tattooing; if you can work with electricity it’s much quicker.

“One of the potential drivers for the tattoo’s fall from grace may well have been this opening up to people with less means. From then on in tattoos were part of British society at every level.”

Tattoo: British Tattoo Art Revealed is open at the National Maritime Museum in Cornwall until 7 January 2018.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.