Can cyberpunk ever reclaim its radicalism?

- Text by Gerry Hart

Amid a culture landscape defined by nostalgia, cyberpunk – a subgenre of science fiction set in a lawless subculture of an oppressive society dominated by computer technology – has enjoyed a resurgence. In fact, last year might have felt like the perfect moment for video game developers CD Projekt Red to release their long-awaited open-world game, Cyberpunk 2077.

Cyberpunk 2077 – which originated as a tabletop roleplaying game created by Mike Pondsmith in the late 1980s – takes place in the universe of Cyberpunk 2020. For eight years, the veteran developers behind the acclaimed ‘Witcher’ games built player expectations up and up, only to deliver an expensive, glitchy mess towards the end of last year. But even beyond its technical failings, Cyberpunk 2077 points to a worrying malaise in its namesake genre.

Be careful when backing up as you may get yeeted into oblivion #Cyberpunk2077 pic.twitter.com/OHHiTdCs4g

— Cyberpunk 2077 – CYBERPUNKINSIDER.COM (@PlayCyberPunk) February 23, 2021

Like all science fiction, it is impossible to separate cyberpunk from the circumstances that shaped it. In the second half of the 20th century, the neoliberalism championed by Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan sought to reorient social, economic and political life around the free market. With the collapse of the communist bloc in the early 1990s this market-centric ideology cemented itself as the dominant modus operandi of the global economy. Francis Fukuyama would infamously declare this the end of history and the new dominant system was afforded a sense of triumphalism.

Emerging from this environment, cyberpunk instead looked to the future with a marked cynicism. Instead of extolling the virtues of the new order, touchstones like William Gibson’s Neuromancer, Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash and Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop painted a world where the convergence of capital, technology and the self would only serve to disempower the individual.

While CD Projekt Red’s Cyberpunk 2077 draws on these influences, it differs in its intent. Cyberpunk 2077 is first and foremost a product to be sold for a profit, and as such, the aesthetic and narrative trappings of its namesake genre exist as hypernormalised signifiers divorced from their original political meaning. This leads the game to reproduce a number of the cyberpunk’s more pernicious tropes without commentary.

Orientalism, for instance, has been a problem in cyberpunk since its inception which again, can be partly attributed to the era which birthed it. The 1980s were the peak of the Japanese economic miracle, when a number of Japanese companies like Sony and Nissan became increasingly prominent in western nations, leading to racially animated fears that the west would be outcompeted by Asian capital.

By the 1990s this bubble had burst, but the trope has persisted ever since. Japanese zaibatsus dominate Cyberpunk 2077, with the all-powerful Arasaka corporation towering above them all. Why Japanese capital is so dominant in Cyberpunk 2077’s world, or how exactly it is any worse than its western counterparts, is never interrogated. It’s simply there because that’s cyberpunk.

Orientalism is just one of many diluted trappings the game reproduces. Another is the genre’s characteristic hopelessness. Cyberpunk protagonists like Neuromancer’s Case or Snow Crash’s Hiro Protagonist are defined by their alienation, and this holds true for V, Cyberpunk 2077’s protagonist. A mercenary nominally controlled by the player, V is all but powerless to affect their circumstances, often reacting to the world around them with a resigned nihilism.

Even the characters who rail against the system only serve to add to this aura of disempowerment. The Mox, for instance, are a collective of sex workers who banded together for mutual aid and defence. Yet when asked by V, their leader proclaims they are a business, and that “anyone who isn’t a Mox, isn’t her problem”. Their radicalism has to conform to the cold, transactional reality of Cyberpunk 2077’s world.

The best example, though, comes in the form of the titanic figure of Johnny Silverhand, rockstar, revolutionary and long-time staple of the Cyberpunk universe best known for destroying Arasaka’s corporate headquarters with a nuclear bomb and played now by Keanu Reeves.

During the events of the game, the player and Johnny meet a long-time fan of Johnny’s band Samurai who still idolises him and sells his records long after they have become passé. At this, Johnny bemoans that his calls for revolution have gone unheeded in lieu of nostalgia. According to Pondsmith, Johnny Silverhand was originally inspired by David Bowie, yet now he is much more reminiscent of Kurt Cobain who to quote Mark Fisher, “knew he was just another piece of spectacle” and that “his every move was a cliché, scripted in advance”.

Of course, Cobain never blew up any corporate headquarters, but even this deed only serves to underline the impotence of Johnny’s rage. In one conversation, V observes that Johnny’s hatred for Arasaka is a mask. That he is a sad, broken man who doesn’t truly know what he wants. As with the game’s orientalism, Cyberpunk 2077 doesn’t seek to interrogate why its world is structured as it is. It doesn’t interrogate any systems of power, or it’s world’s major institutions. Corporate dominance is, for all intents and purposes, not a result of particular economic or political forces but are natural and unchangeable and any resistance to them is doomed because, once again, that’s cyberpunk.

Some might argue that this is the point – that this sense of impotence is an integral part of cyberpunk’s message. There is some truth to this. But clearly, the genre has been intimately connected with politics in the past. William Gibson published Neuromancer in 1984, the year of the Miners’ Strike in the UK and Thatcher’s government violently breaking organised labour as a major political force. This same year also saw the release of Robocop, coinciding with Reagan’s landslide re-election in the US. Back then, neoliberalism was a new force taking the world by storm. Now, as we enter the 2020s, neoliberalism is no longer a rising tide but an entrenched system. It is not enough therefore to repackage the imagined futures of past decades as consumable, escapist entertainment when the dystopias of cyberpunk are our lived reality.

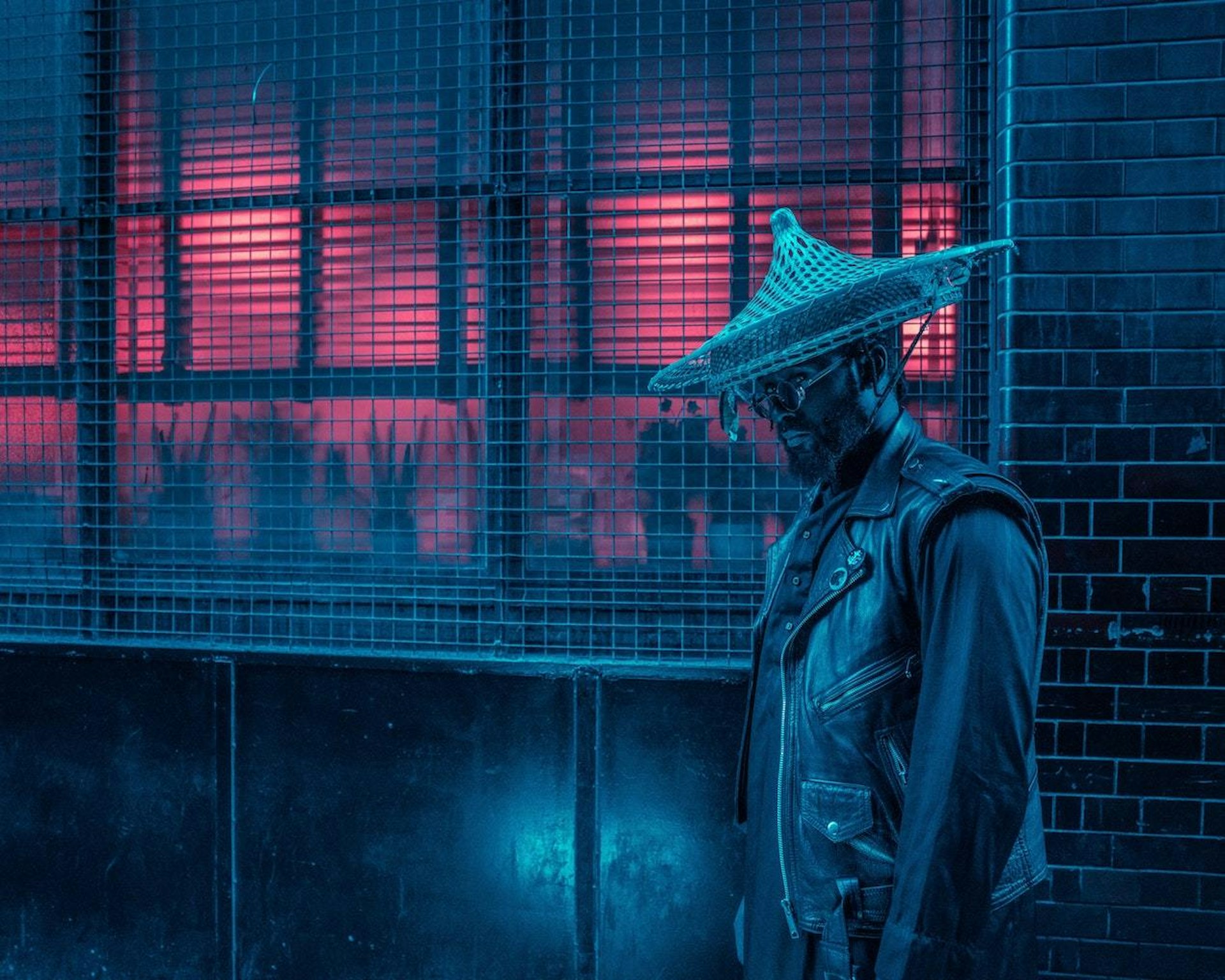

If, then, Cyberpunk 2077 represents a depoliticisation of the genre, how might we revitalise it? First, it is vital we recognise that cyberpunk fiction has become too enamoured with its own aesthetics. As many critics have noted, Cyberpunk has become more cyber and less punk lately. Any work operating within the genre should seek to critically engage with the tropes of the genre going forward, interrogating their use and discarding or modifying them as necessary.

This would certainly be a useful start, but we can do better than simply modifying our existing narratives of disempowerment. This could take the form of envisaging radically different futures, such as with John Akomfrah’s video essay The Last Angel of History, which blends Afrofuturism and cyberpunk in order to explore how Black history and culture might allow us to re-imagine the future.

Similarly, solarpunk has emerged as a more optimistic response to the pessimism of cyberpunk, conjuring utopias beyond capitalism and climate collapse. Even traditional cyberpunk narratives themselves are defined by a shadowy underworld of alienated mercenaries and hackers, fertile grounds for more revolutionary stories. After all, to quote the greatest cyberpunk luminary Billy Idol, could we not all do with a shock to the system right about now?

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.