Capturing resistance among Canada’s indigenous people

- Text by Miss Rosen

- Photography by Pat Kane

An Algonquin Anishinaabe member of the Timiskaming First Nation, Canadian photographer Pat Kane was raised in a mixed-race home. “My mother was born on a reservation in Quebec and my father grew up in an Irish immigrant family,” he says.

“It wasn’t until I moved to Yellowknife [in the Northwest Territories] that I reconnected with my Indigenous side. The people here are so proud of their culture and their elders. That was a turning point for me.”

Photography provided Kane with a path to explore his identity by documenting the lives of the local Indigenous community, who are related to the Dene people of the Navajo Nation. Although Kane isn’t from their nation, his work over the past 20 years has established a bond of trust, understanding and respect.

After thirty-nine years as a couple, John Doctor, 65, and Pauline Zoe, 58, get married in St. Micheal’s Catholic Church in the Tłı̨chǫ community of Behchokǫ̀, Northwest Territories.

Although many outsiders have traveled to Indigenous communities, their focus can be exclusionary, framing stories through the lens of fetishistic exoticism to fit a preconceived narrative. Recognising the importance of showing a complex and multifaceted portrait of contemporary life, Kane is exhibiting works from the series Here is Where We Shall Stay, an exploration of the impact of the Anglican Catholic Church on the Dene.

In recent months, more than 1,300 unmarked graves have been found at four sites once home to Canadian residential schools — just the latest horror in a 500 year genocide waged against Indigenous peoples of the Western hemisphere.

Between 1894 and 1947, the government mandated some 150,000 Indigenous children enroll in boarding schools run by the church, which stripped them of their ancestral culture, removed their legal identity as Indians, and subjected them to psychological, physical and sexual abuse. After the mandate was lifted, schools continued to run until another 50 years, the last one finally closing its doors in 1997.

The Aurora Borealis (Northern Lights) appear over a shed in the Dene community of Dettah, Northwest Territories.

Drummers pray and sing during a ceremony to “feed the fire” at Kokètì (Contwoyto Lake), Northwest Territories – a way to ask the land for safety and protection.

“The Northwest Territories is ground zero for residential schools — a lot of people living here today attended them,” says Kane. “Indigenous people have gone through a lot of traumatic colonisation because of the church. I wanted to explore that and the relationship between Indigenous spirituality and more formalised Catholic and Anglican [religion].”

Used as a tool of imperialism, Christianity has been used to support genocide, slavery, and oppression for centuries; but perhaps more curious is the hold it has had on those who it was used against, as many have found solace in the story and teachings of Christ.

“It’s amazing how people who have been to residential school still pray and go to church every day,” says Kane. “I wanted to explore this complex relationship but also acknowledge the people moving forward and reclaiming their own identity and sense of place, doing traditional Indigenous things.”

In Here is Where We Shall Stay, Kane shows how the two sides have fused together as part of a shared history of survival and resilience becomes a form of resistance itself. “Indigenous people are not resentful, hateful, or vengeful,” Kane says. “They just want to move forward in a positive way.”

The Tłı̨chǫ flag representing four Dene communities, the water and midnight sun, stands on the barrenlands at Kokètì (Contwoyto Lake), Northwest Territories, a tradtional harvesting area of caribou for centuries.

A dog walks near the Catholic Church of the Holy Family in Łutsël K’é, Northwest Territories. The church was built near the present day settlement in the 1930’s and moved to its current location at the tip of the penninsula – one of the tallest and most recognisable structures in the community.

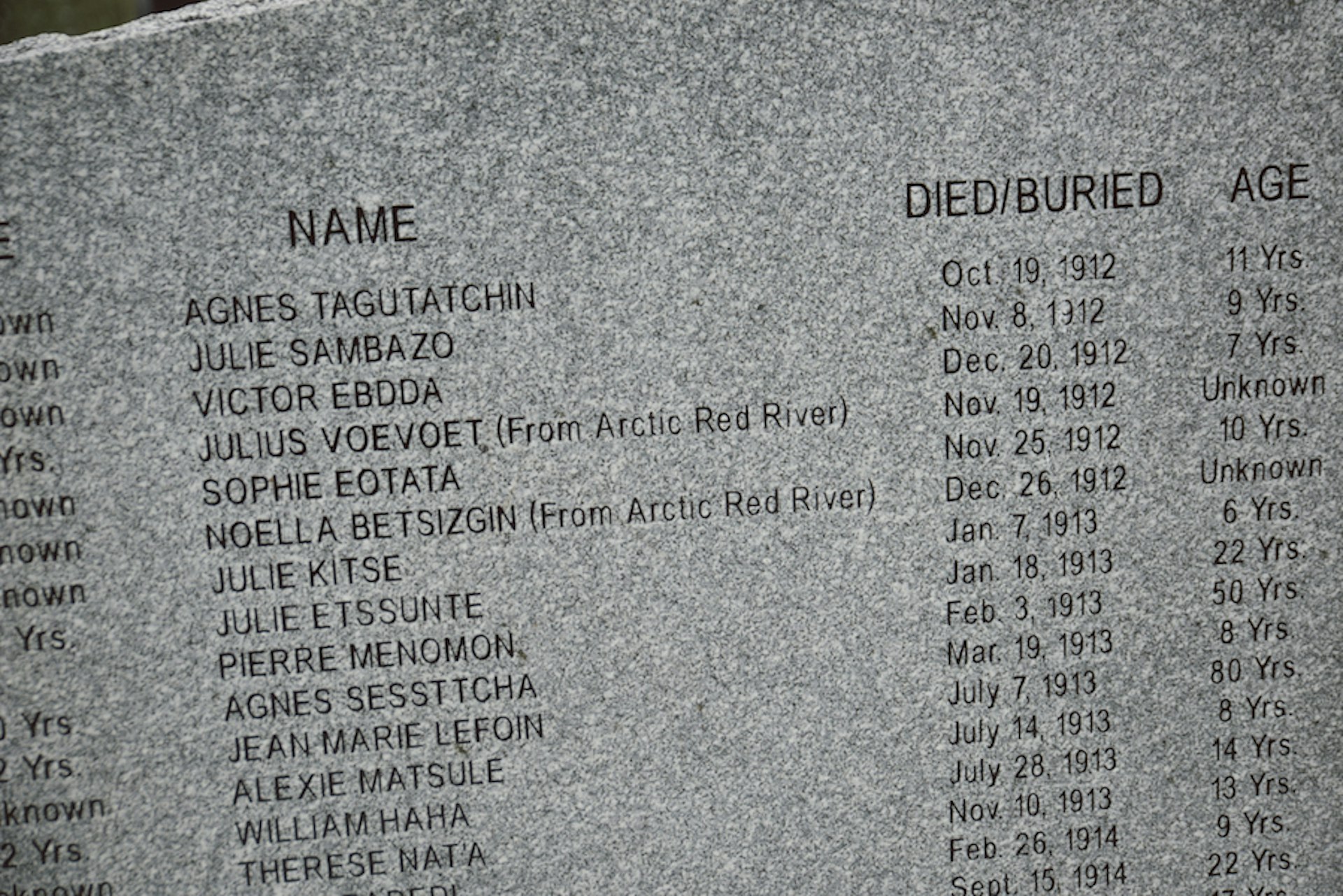

A memorial honouring the Dene and Metis people – many of them children who attended Sacred Heart Residential School – are buried at Deh Gáh Got’îê (Fort Providence), Northwest Territories. The burial site was here between 1868 and 1948.

Sarah Erasmus holds a family photo taken in the 1980’s at her home in Ndilo, Northwest Territories.

Instant photos of Terri Enzoe, Jaysen Michel and Jennifer Michel cover an archive photo of students and missionaries of the Chief Julius residential school in Teet’lit Zheh (Fort McPherson). Terri, Jaysen and Jennifer are land and water protectors from Łutsël K’é, working as part of the Ni Hat’ni Dene Guardians to preserve their homelands.

Sage burns in a smudging bowl on Lila Fraser Erasmus’ dining room table. “We’re connected to the land, it is part of who we are as people, we are inseparable from it,” she says.

Pat Kane: Here is Where We Shall Stay, presented by Indigenous Photograph, is on view at Photoville, Brooklyn, through December 1, 2021.

Follow Miss Rosen on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.