Cosey Fanni Tutti: fearless provocateur, ultimate outsider

- Text by Cian Traynor

- Photography by Portrait by Oscar Foster-Kane. All others courtesy of Faber.

Cosey Fanni Tutti is sitting on stage in front of a packed-out crowd at London’s Rough Trade East, talking about her distrust of acceptance.

“It makes me feel like I’ve done something wrong,” she says, dressed all in black and exuding a no-nonsense air.

Given that the audience is filled with admiring artists, she may have to get used to the idea. Crammed in-between racks of music are Marc Almond, John Grant, Tim Burgess of The Charlatans, fashion designer Pam Hogg and Nik Void of Factory Floor to name just a few.

They’ve gathered for the launch of Cosey’s tell-all memoir Art Sex Music – not just to pay their respects, but to see her reclaim her own narrative after years of myths, misconceptions and others taking credit for her work.

Posing nude, July 1979. © Laszlo Szabo.

Cosey has been a tireless radical in music, art and performance for decades – from notorious collective COUM Transmissions and the groundbreaking group Throbbing Gristle, to her work as a multidisciplinary artist and inspirational speaker.

But that’s also made for a long journey of conflict, controversy and barrier-breaking determination.

Born Christine Newby, Cosey grew up as a rebellious teen in Hull, where she was thrown out of the family home and later cut-off from her parents over her countercultural pursuits.

Police viewed Cosey as part of the city’s ‘troublesome elements’ and harassed her until she left for London in 1973, where she would be threatened with indecency charges over her art.

Recording session for 20 Jazz Funk Greats, London, 1979. Photo by Chris Carter.

It involved exploring self-image within the sex industry – modelling for top-shelf magazines, appearing in porn films as well as stripping – before feeding those experiences back into her work. But by that point, hysterical reactions had become the norm.

As part of Throbbing Gristle – widely credited as the originators of industrial music (a term they coined) – Cosey made sure their performances provoked audiences into thinking for themselves.

There would be walkouts and brawls, mutilation and police raids, but they came to epitomise music at its most transgressive.

Cosey & Gen by John Krivine, 1969.

Behind the scenes, Cosey kept Throbbing Gristle afloat by maintaining various jobs and balancing out the abusive, manipulative behaviour of bandmate Genesis P Orridge.

When that became unbearable, she and partner Chris Carter (also a member of Throbbing Gristle) moved to Norfolk. They continued to record as Chris & Cosey (later Carter Tutti) – a relationship that endures to this day.

Now the world is finally catching up to Cosey Fanni Tutti. Her art has been bought by the Tate, Throbbing Gristle rank among the most important artists of their era, while Chris & Cosey have inspired successive generations of electronic artists. Connecting it all is an appetite for life that, in Cosey’s own words, remains “full-on”.

Reading your book, I got the sense of someone who’s refreshingly headstrong and secure when, from the outside, you had every reason not to be. How did your upbringing shape that?

In retrospect, I think I had quite a good balance: the sensitivities of my mum combined with the expectations of my father, who pushed me into the male world because he didn’t have a son. He travelled a lot in the Navy and so I think that was instrumental in me developing a broad worldview. My point of reference was always outside of Hull.

Growing up in a post-war era, there was a whole attitude of, ‘Tomorrow could be your last day’ – quite literally when it came to the Cuban Missile Crisis. That makes you think, ‘I’ll make the most of what I got. What is there that I might want?’ It certainly wasn’t getting married, settling down and having a house. [Laughs]

‘Ritual Awakening Part 2’ art action, Amsterdam’s Bar Europa Festival, 1987.

You must have been called so many different things throughout your career. The pressure to conform would have been enormous. How did you manage?

I didn’t fit into any lifestyle and I felt the one I made for myself suited me. And because I had to fight to get there, being run out of home and not relying on anyone else, I never thought I’d have to justify the way I am. I wasn’t looking to fit in, so I didn’t feel like I had to defend my stance at all.

There were never any moments where you questioned it? No moments of self-doubt?

As a kid, whatever I did outside the house was considered wrong… and I could never find a good reason why. But because I had a like-minded ally in [childhood friend] Les, we backed each other up. We felt assured in finding our way.

Out and about in Los Angeles with friends Kitten, Eric and Skot, 1976.

When Genesis was violent towards you, you recognised him as being lost and felt sorry for him. Most people never get to a point where they have the perspective to frame things that way…

Well, I had feelings for him and I was made to feel like these things were my fault, that his reaction was a response to my actions. Why he did that to me, I have no idea. That’s a problem he had to deal with himself. My problem was making sure my life, and the people around me, were okay.

I was used to fighting. Hull is a tough place. Every day involved confrontation. Looking back, it shouldn’t have been in my own home. But it had been an everyday thing. It was only when I met Chris that it was pointed out to me that it wasn’t a good situation. [Laughs]

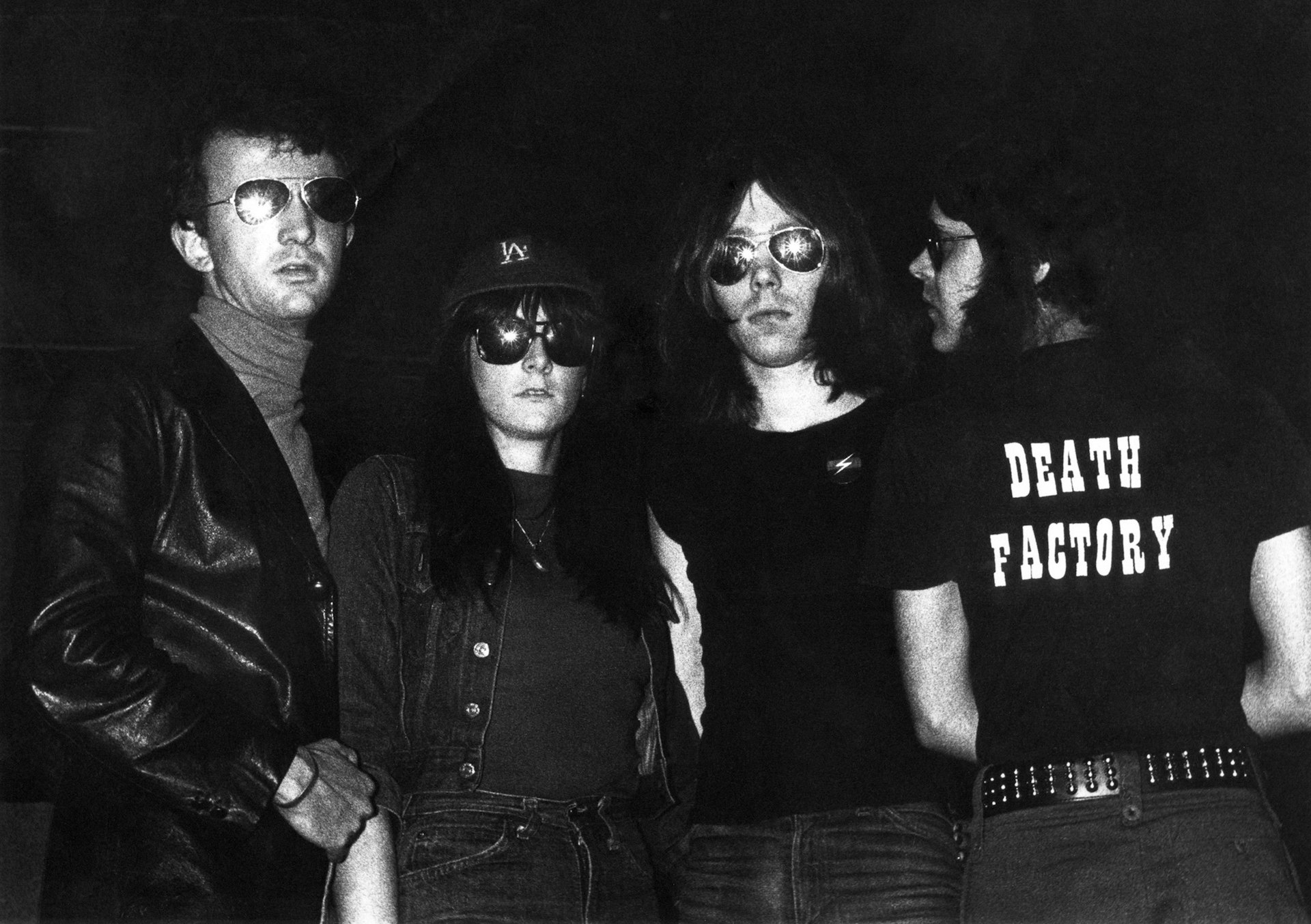

TG promo shoot with Jon Savage, Victoria Park, London, 1981. © Industrial Records.

Do you still consider yourself an outsider?

Yes, I do. Sometimes when I go out, I suddenly feel like more of an outsider than I recognised previously – because I never thought about it. I just did my own thing, which has always been a natural progression. It’s only when you take that from private to public that you discover people find it transgressive.

Doing things like bringing your child to school makes you realise you have a different mindset completely. Once, when Nick [her son] was at junior school, one of the teachers heard that I played music. She said, ‘Would you come in and sing some songs for the children?’ [Laughs] I thought, ‘Eh… no.’

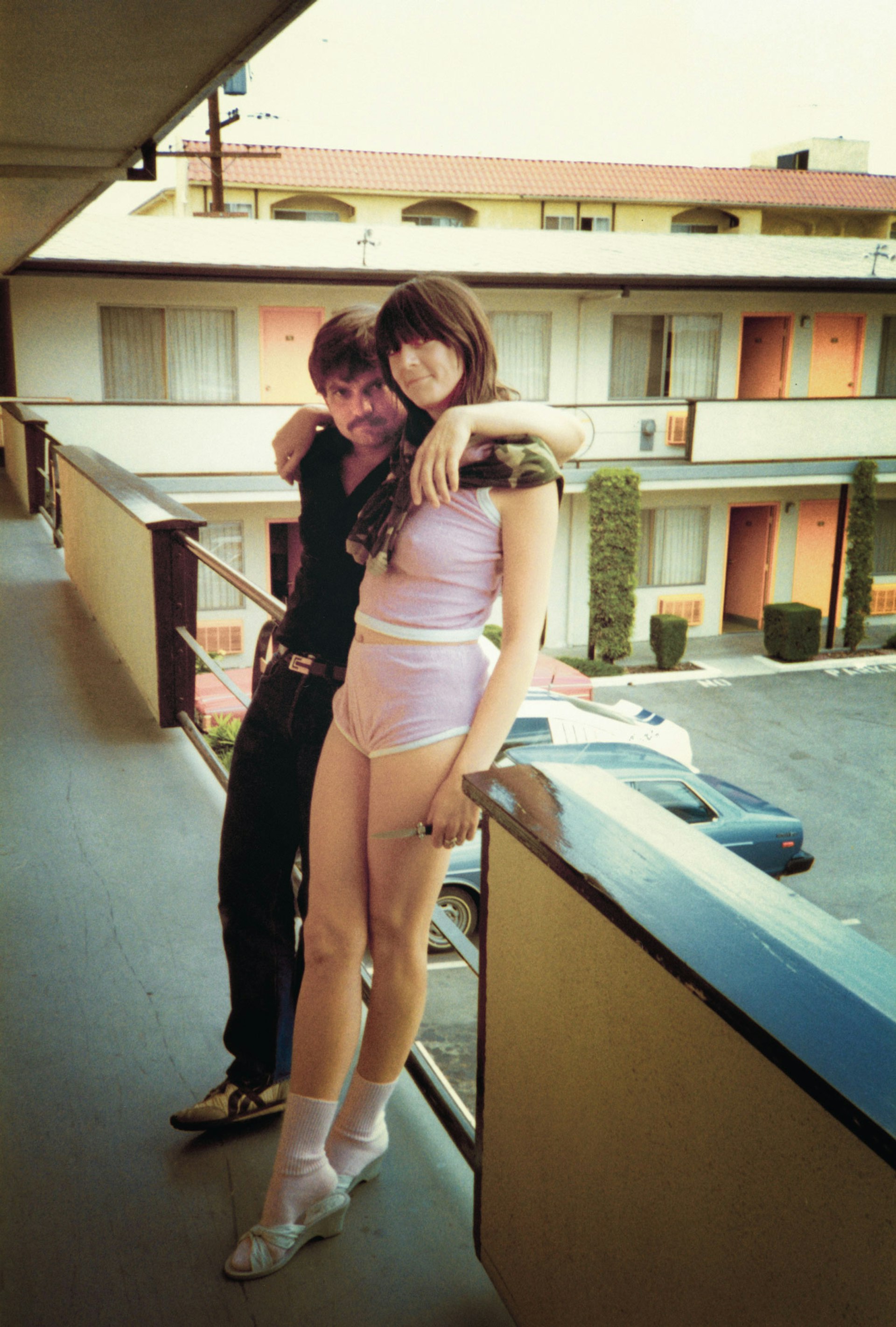

With Skot at the Throbbing Gristle motel, Los Angeles, 1981. Photo by Chris Carter

Do you think there’s as much of an ‘outside’ to occupy anymore?

Definitely. The situation is worldwide now. There’s so much trouble – religion, racism, everything all in one – that it makes people feel like outsiders more than ever. And what do you do? Everyone is a human being. There should be no prejudice. We should be there to help one another rather than killing each other. But I can’t think of another time as frightening as this.

Against that backdrop, how much does independence matter?

I think independent thinking is so important. The only way you get that is by taking time to find yourself and assimilate things through your own mindset. There’s a tendency for people just to accept other’s opinions as their own. The facts given on the internet are clearly not always facts, as we’ve seen.

You don’t have to accept the overarching bland view of the world or the money orientated attitude to life that people have now. That angers me. I recognise an element of survival that wasn’t there in the ’70s, as you can’t easily squat anymore. Every era brings its difficulties and struggles but I think there’s always a way around it if you’re determined.

Creative independence is especially important. When I hear music or see art, I want to feel like it’s come from deep within that person; that they’re relating something from themselves, not from the consensus. I don’t want a piece of art because it looks pretty and goes with the curtains. That’s boring. I want something that’s going to make me think.

Recording session for 20 Jazz Funk Greats, London, 1979.

How have you and Chris been able to balance expression through art with making a living from it?

We’ve been lucky. There have been times when we were really, really broke and had hardly anything. I would easily get a job in a factory to just keep doing what we’re doing. But Chris would always have faith and say, ‘We don’t need to do that. It’ll be fine.’ Somewhere in the middle, we’ve always managed. Maybe it’s as simple as being careful. We never have holidays; we buy equipment instead. [Laughs]

Was it painful that your parents didn’t come to appreciate what you did with your life?

No, because I didn’t seek approval from anybody. It’s nice when it happens but because I’m not used to it, it’s very difficult for me to accept compliments about my work. I’m more comfortable with criticism. [Laughs]

That’s the way it’s been throughout my life. I didn’t expect my parents to understand who I was or what I was going to do. What you need is the relationship between child and mum and dad. That’s what I lost through being what I wanted to be, just because they were a product of their era.

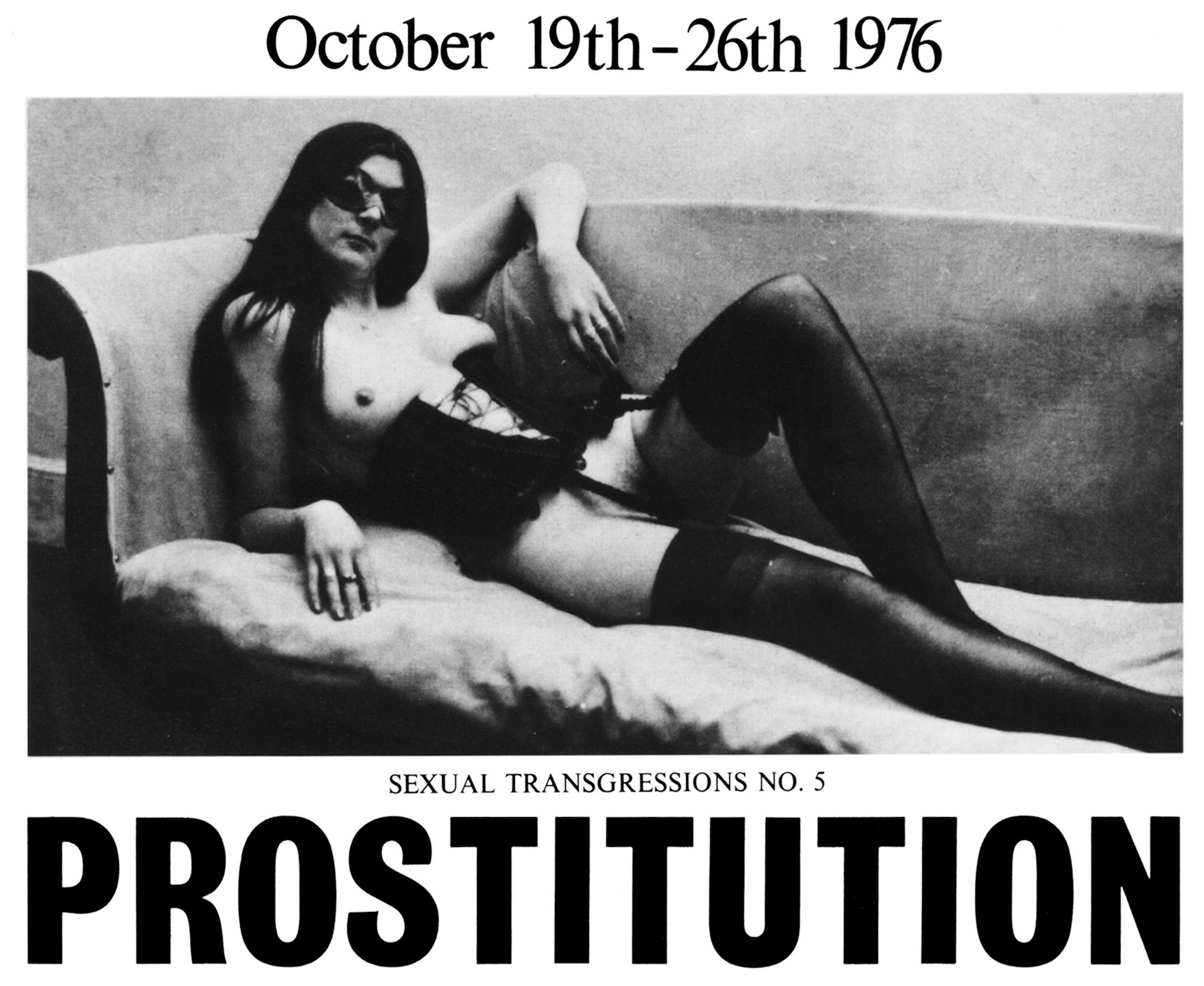

Exhibition poster for ‘Prostitution’ at London’s ICA, 1976.

Did you feel like Throbbing Gristle was misunderstood?

We didn’t seek understanding. We didn’t want people saying, ‘You’re very good!’ [Laughs] We were just expressing our feelings about the world and other people’s transgressions against humanity. And that is uncomfortable for people. It should be!

What advice would you have for someone who isn’t as fearless and doesn’t feel like they have ownership over their life?

But why would someone think they don’t have ownership over their life?

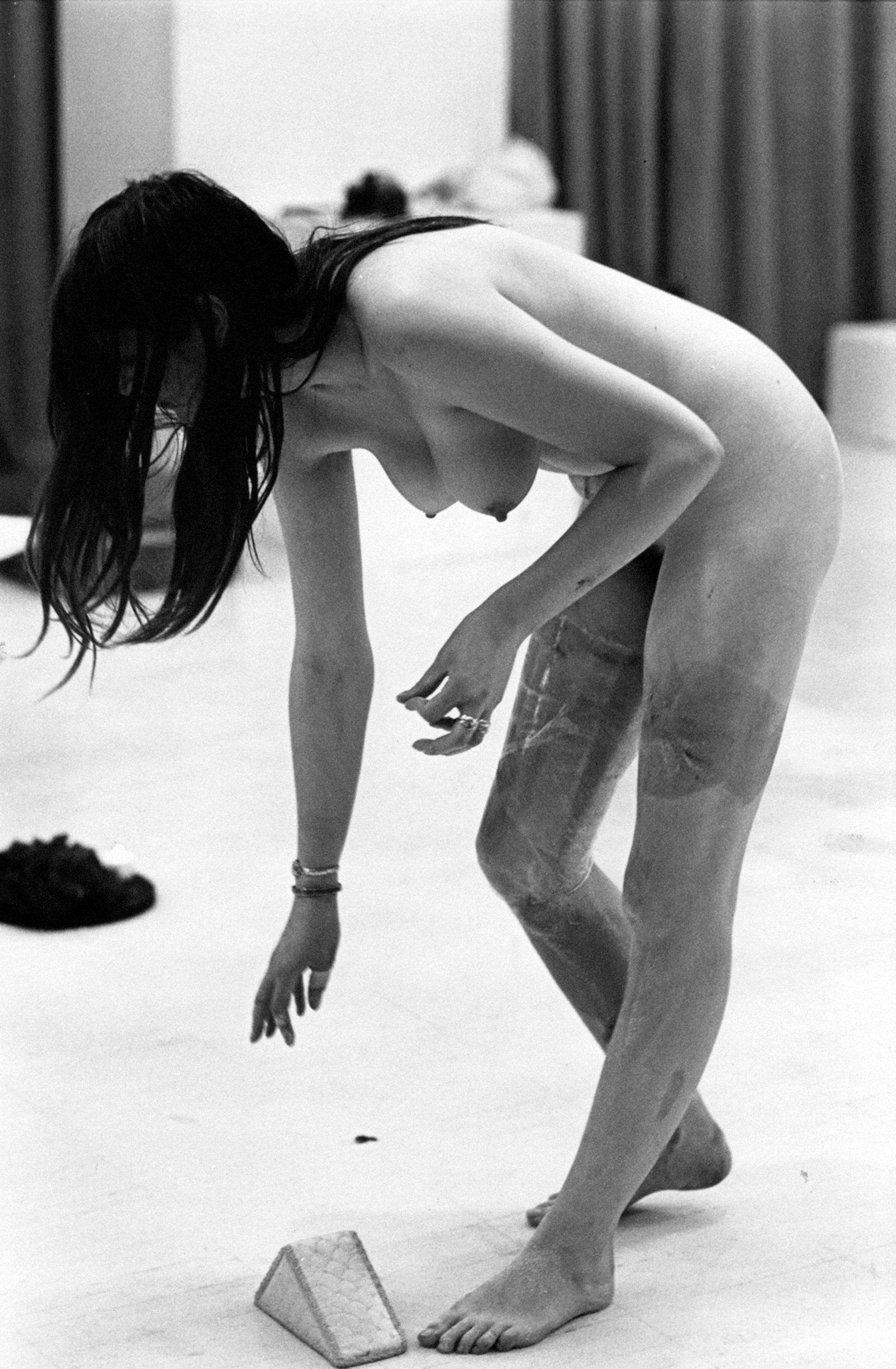

‘Studio of Lust’ art action, Southampton’s Nuffield Gallery, 1975.

I think you’d be surprised! So many people are stuck in bad relationships or dead-end jobs and can’t see a way out to do or be what they want.

Well, I’ve been in that situation… before I left [London]. I had everything there: Throbbing Gristle, Industrial Music [their own label]… but I wasn’t happy. Leaving was a huge sacrifice. It all fell apart. After eight years, I took enough with me to fill half a transit van. I gave up everything that I’d already done to be who I felt I needed to be.

It’s a big ask… so I’m not judgemental if people feel they have to stay in a situation. I’ve seen it a with a friend of mine who stayed in an unhappy marriage for years. Sadly, she’s gone now and never had the happiness she yearned for. We’re only here once! You’ve got to make the best of it however you can.

At home in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, 2017. Photo by Oscar Foster-Kane.

You don’t want acceptance. But is there any satisfaction in the world catching up to your ideas?

Yeah, it’s weird: most artists aren’t around to see their work recognised for what it was for them when they made it. I’ve been lucky with my art, with Throbbing Gristle, with Industrial Music and with Chris & Cosey. I can’t believe that I’ve had all that in my lifetime. To come back and revisit it through the eyes of people from that time and new fans is quite a gift. I cherish that.

Art Sex Music is published by Faber.

This article appears in Huck 60 – The Outsider Issue. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.