The Japanese cyclists seeing their city differently

- Text by Sophie Knight

- Photography by Daichi Koda

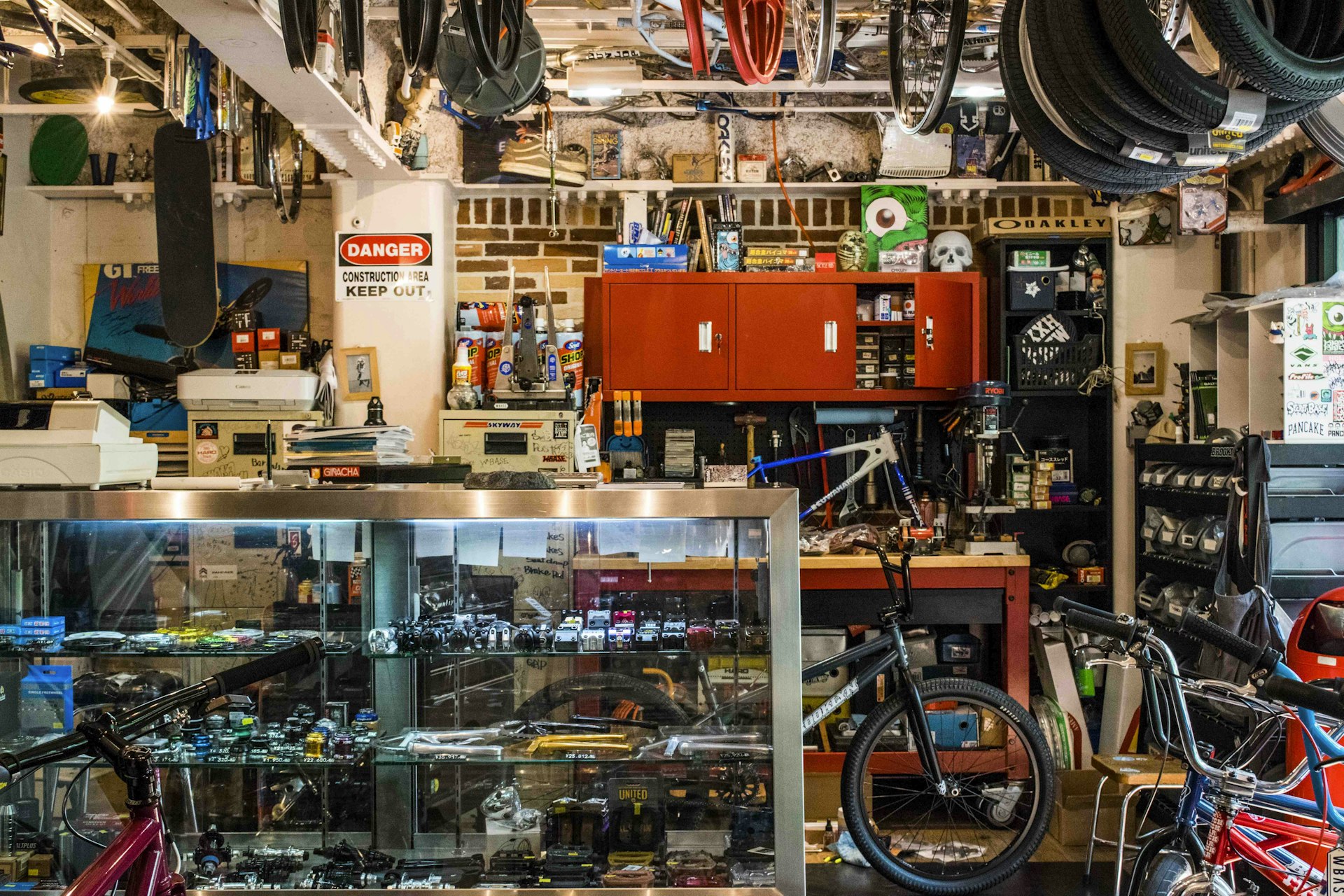

Tucked away in a Shibuya backstreet is the epicentre of Tokyo’s cutting-edge cycling scene: W-BASE. Jammed to the rafters with rainbow-colored cranks, chainsets, brackets and of course their famed W-LINE BMXs and fixies, this single-speed specialist store has been pushing the boundaries of riding in Japan’s capital since 2004.

Bike junkies from all over the world make pilgrimages to get their two-floor fix of goodies, while a local community of messengers, trick ends and serious bike commuters all rely on the store for honest advice, reliable repairs and hip new parts.

“We started out by supporting messengers,” says staff member Toku, who started working at the store after W-BASE sponsored him. “If they punctured a tire or something went wrong with their bike they could bring it to us and we’d fix it for a discount. We often served as an alleycat checkpoint, too.”

In the quiet street outside, staff show customers how to ride fixed-gear and local riders practice their 360s, bunnyhops and wheelies. The store also holds regular photography exhibitions that see crowds spilling out into the street on opening nights.

Northern European cities are often touted as the cyclist paradises of the world, but to those in the know, Tokyo steals the crown. ere may be precious few bike lanes and the ubiquitous mamachari city bikes clogging up the pavements are nothing to write home about. But get your hands on a proper commuter bike and head onto the main avenues and you’ll discover the euphoric experience of gliding through one of the world’s most populated cities as if you were the only person in it.

Many cyclists in Tokyo are driven by the high-octane thrill of coasting along the surreally smooth and wide main roads, but an equal number count on their bike as the main form of transportation to escape the discomfort of rush-hour trains, infamous for having white-gloved station staff push people further into sardine-tin carriages. Add to that Tokyo’s oppressive humidity for half the year, and the suffocating heat pumped through trains through the winter months, and you have a pretty powerful incentive to rely on bikes to get you around instead.

An increase in cyclist commuters has been fuelled by the fear of an earthquake shutting down public transportation, as well as a boom in fixed-gear bikes that started in the late 2000s. Given Japan’s cycling heritage and highly revered master bicycle makers, it’s curious that fixies didn’t catch on sooner. But until around 2007, most people thought the steel NJS frames coveted by Americans belonged in the Keirin Velodrome and not on the streets.

Teppei “Nasty” Iwabuchi was one of them. He started skating at 13, and was aiming to go pro. He wasn’t interested in fixed-gear bikes until he saw a video of San Francisco’s MASH crew doing crazy BMX-style tricks on them. “I think it was seeing Gabe, the cameraman, who did a bunnyhop to get on a step and then a wheelie. I was instantly hooked. I thought, ‘I want to do that,’” he says.

Teppei had ridden BMXs before and so was able to do bunnyhops pretty quickly. He then got into skids, which are still his favourite move. Being one of the first in Tokyo to try out tricks on a fixed wheel, he soon turned heads. “Because it was so early on and the scene was so fresh, whoever did something for the first time won,” he says.

But Teppei’s talent went beyond beginner’s luck, and with marathon practice sessions of six hours or more, he was soon one of the hottest riders in Japan. While most of his friends and competitors moved onto 26” wheels and sturdier frames to withstand increasingly complex BMX-style tricks, Teppei stuck to 700c wheels and developed his own unique style that got him sponsored by Fuji and later poached by W-BASE. The store’s W-LINE brand created a signature frame for him with fat 700c tires, the Durcus-One ‘NASTY’.

“My style is all about how to show off simple tricks in a cool way. I’m not really interested in complicated tricks. I want to get the simple things perfect,” he says.

Teppei’s unbelievably crisp 360s and tricks have been immortalised by photographer and videographer Seitaro “Say” Iki, photographer and founder of Devour Films, a collective which documents the Japanese cycling scene. Living in Fukuoka, a port city in Kyushu, the southernmost of Japan’s four main islands, Seitaro felt compelled to start making a record of the riders around him.

“When I started taking photos I mostly shot my friends just because I wanted to show other people what they were doing,” he says. “But as I continued taking photos, I realised that everything was changing: the town, the people on the scene, the shape of the bikes and how people rode them. It was interesting to look back and see how it had all transformed and what things looked like a few years before.” Seitaro is a prolific shooter, which is why he called his agency Devour Films.

“I think that with anything you do, whether it’s bikes or something else, you’ve got to do it at out, all the time. Just do it as much as you can. I’d take photographs until I couldn’t anymore: photos of the town, moments around me, the landscape, moments between people, opportunities, anything. I just want to devour it all.”

When Seitaro started taking photographs around 2010, the fixed-gear scene was at its peak. Every Friday night, around 100 cyclists in Tokyo would gather in Shiba Park in the shadow of one of the city’s most iconic landmarks, the red-and-white-striped Tokyo Tower, to ride around, practice tricks, and make new friends. But the scene was dealt a blow in 2011 by a new law banning the riding or sale of bikes without back brakes. The move was prompted by a spate of accidents involving fixed-gear bikes in which several people were injured and one woman died. The police saw the only way of stopping on a fixed-gear bike – resisting the turn of the pedals – as unsafe, and began stopping and arresting cyclists who rode without a back brake.

Many riders quit overnight, deciding that if they had to deface their bikes with a back brake (either by drilling a hole for the cable or snaking it awkwardly along the top tube) then they’d rather not ride at all. However, the new generation who took up riding fixies after the law came in to effect, don’t mind having brakes. Japan still has some of the world’s best fixed-gear freestyle riders, including Teppei’s W-BASE stablemate Marco, who regularly travels overseas to showcase his mind-bending stunts.

And thanks to the boom in fixies, there are now many more stores in Tokyo catering to commuters who are looking for a steed with a bit more air than the average mamachari.

“The increase in bike commuters may have something to do with the way cycling changes one’s perception of the city,” says Ryohei Morita, a BMX rider and graphic designer who co- founded See You Soon, a gallery in Shibuya specialising in street culture, art, and fashion that is considering a collaboration with W-BASE. “Riding is a way of enjoying the city infrastructure in a different way; jumping up and down steps, for example, or running along ledges with pegs. Playing around. But because sometimes you break things, I think it’s only possible to do that in some areas of Tokyo,” he says.

Ryohei says one of those places is Miyashita Park, an elevated area in Shibuya about a hundred meters from W-BASE with a Nike-sponsored climbing wall and five-a-side football pitch that is also a magnet for street dancers practicing their routines. The proximity of W-BASE probably has something to do with the number of BMX riders and cyclists also hanging out and pulling tricks on the nearby stairs. While Tokyo’s efficient and punctual train system makes it easy for many commuters, Ryohei says cycling transforms one’s experience of the city – for the better.

“In Tokyo, and maybe anywhere, if you ride the train you get in at one station, get out at another, you just skip across the city. Sometimes people even just go one station even though it would be quicker to walk. When you ride a bike you realise this and you get to know the city in a different way than other people. The map of Tokyo you have inside your head is different.”

This article first appeared in Lines Through The City, a newspaper – featuring stories of cyclists and skateboarders – made in collaboration with Levi’s.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.