Building bridges to the past with survivors of the Armenian genocide

- Text by Diana Markosian as told to Andrea Kurland

- Photography by Diana Markosian

“I was never interested in pursuing work on the Armenian genocide. When I started this project, it was still just a vague historical narrative. I knew that, in 1915, the Ottomans initiated a policy of deportation and mass murder to destroy the Armenian presence. And that, by the war’s end, more than a million people were eliminated from what is now modern-day Turkey. But I had no idea of the personal toll the genocide exacted on my own family, or the sense of connection I would slowly come to feel through the making of this piece.

“I am Armenian, but I was born in Moscow and raised in America. For most of my life, I struggled with my Armenian identity, partly because of the history one inherits. It is something I understood but never fully embraced. Then a year ago, I happened to be in Armenia when a foundation approached me, requesting help in finding any remaining genocide survivors. I perused voter registrations online to see who was born before 1915, and then travelled cross-country to find them. That’s how I met Movses, Mariam and Yepraksia – who had all lived past their hundredth year.

“When I met the survivors and asked them questions, I began to identify with them. They left their homelands at a young age and had no sense of closure with their past. It was something that resonated with me deeply. But this was not my story; I had no authority to tell it. I knew I had to bring them into the process.

“As the three survivors shared memories of their early homes, they each asked me to help fulfil a wish. Mariam asked me to bring back Turkish soil so she could be buried in it. And Yepraksia wanted help finding her older brother who she was separated from after the genocide. I placed an ad in the local paper in Armenia and America, where the family believes he lived.

“I never found him, but I did come back with a container of dirt for Mariam. When she opened it, she thanked me and said, ‘You’ve brought the smell of my village to me.’ I also returned with an image of all three survivor’s former homes.

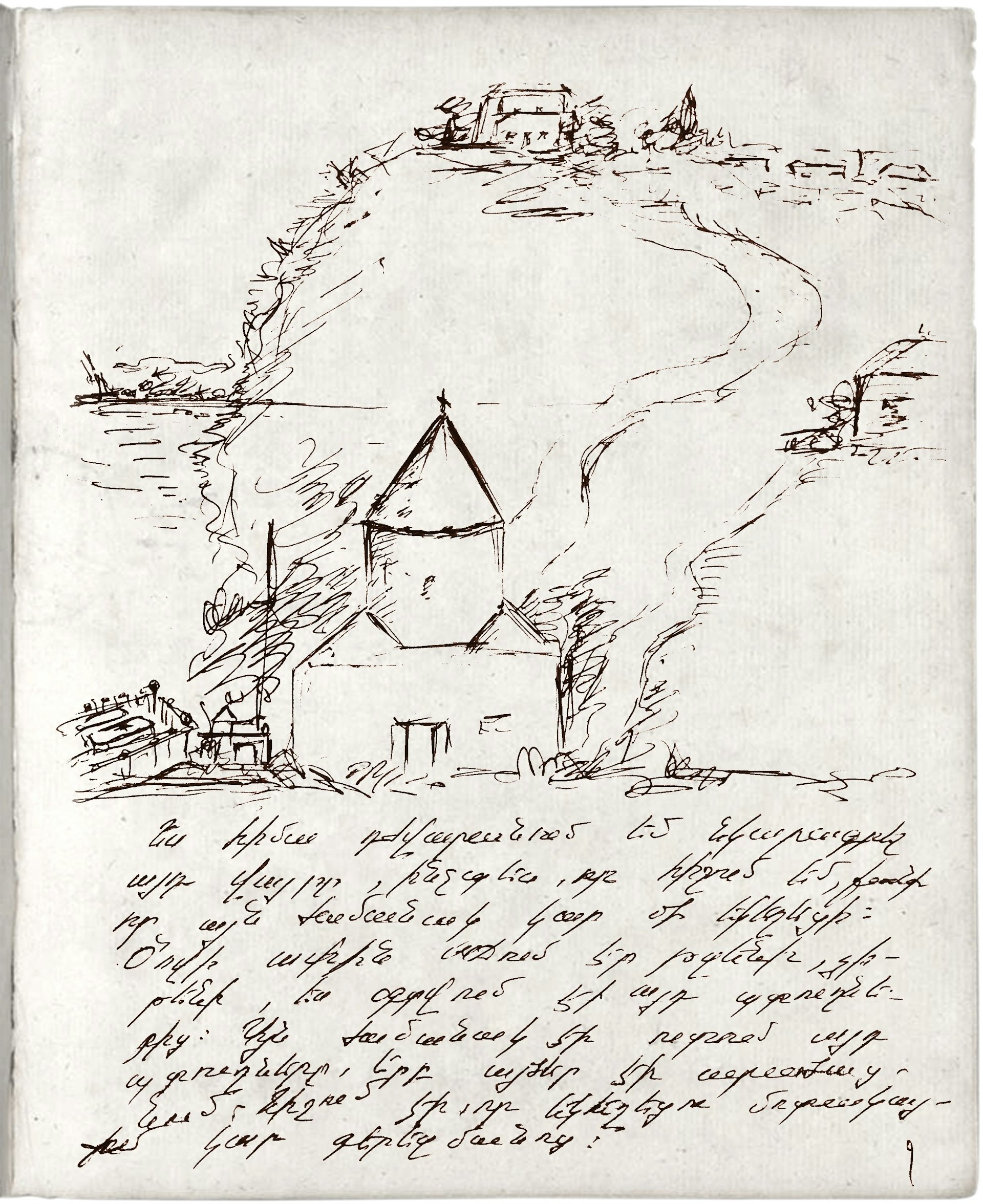

“Movses – who escaped with his father – gave me a hand drawn map of his village in Turkey and asked me to find his church and leave his image there. He hasn’t seen his home in ninety-eight years. When I returned to his village, not too far from Syria, I was with a Turkish fixer who helped me find my way.

“We climbed to the top of the hill together and asked neighbours about the church. I found everything Movses had described to me: the sheep, the fruit he remembered eating, and the sea. It took a while for us to find the church, which is now in ruins. As my fixer watched me place Movses’ image in the rocks, he became emotional. On the way home, he apologised to me for events that happened a hundred years ago.

“I think the most honest work I’ve created has been through collaboration. I realised this when I was working on a piece about my father. When we reconnected suddenly – having not seen each other for fifteen years – taking pictures helped me work through the abyss that existed between us. When I asked my father what he thought of the piece, he said it was missing his voice. This forced me to rethink the way I approach my work, which is often just an expression of my own experiences rather than a shared journey.

“Having a connection with the people I photograph is everything to me. I sometimes wish it wasn’t as important. It would almost make things more convenient, for one. I could go on assignment, make images and return to my life. But for some reason that’s never quite enough. I need more than a beautiful image to fulfil me as a photographer. It doesn’t always need to be a connection as intimate as the work I did on my father, but if I don’t connect, it shows. My work becomes surface level, and I guess that’s my biggest fear as a photographer – making work that is average.

“I am slowly finding my voice as a photographer. I’ve only been doing this for four years, and I am coming to find that my work explores memory – of time and things that aren’t visually descriptive. Faulkner once said, ‘The past is never dead. It’s not even the past.’ I have this jotted down in my notebook and it’s something I come back to – the idea that the past is intertwined with the present and questions of the future.

“Projects like these don’t really have an ending. And I don’t want them to. In the process of making this project, I wanted to give something back beyond my images. These survivors witnessed deportation, death of their own families, and continued denial of genocide. This September, I am launching a print sale to raise 30,000 dollars, which will be allocated to each family.

“Movses, Yepraksia and Mariam have already given so much to me. They helped me feel something for a country that was once so distant. I am now realising my last name is not the only part of my identity connecting me to Armenia.”

This story originally appeared in Huck 52 – The Documentary Photography Special III: Collective Truths. Buy it in the Huck Shop now or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.