Tiananmen's Disappearing Tank man

- Text by Alex Robert Ross

It was a simple, powerful image. As chaos raged all around during the Tiananmen Square protests on June 4, 1989, one man stood in front of a line of tanks brought in to quash the unrest. As the military moved in, the unnamed man in a white shirt held his bags of shopping and blocked might of the military momentarily.

The image was immediately disseminated around the world the next day, its composition so perfect as to appear almost unreal. Since then, it has almost taken on the ubiquity of recycled, reproduced images of Che Guevara; a basic pop cultural signpost of revolutionary sentiment.

But in China, like the memory of the protests themselves, the image is practically unknown. A feature in The New York Times recently drew together the four primary photographers that day, each with their own angle on the image. Charlie Cole, Stuart Frankli and Arthur Tsang Hin Wa all captured the moment. The image that’s been burned into Western minds, though, is the one that Jeff Widener captured for The Associated Press.

His was a close shot, emphasising the might of the military with four tanks stopped perfectly in their tracks, a streetlight emphasising the supposed civilisation that the square intended to cultivate.

Censorship in China is, of course, a difficult and convoluted issue. Amnesty International is just one of the many international groups pressuring China to release those imprisoned on that day and to release figures on the death toll that few can accurately pinpoint. Somewhere between the hundreds and the thousands is the best that many can do.

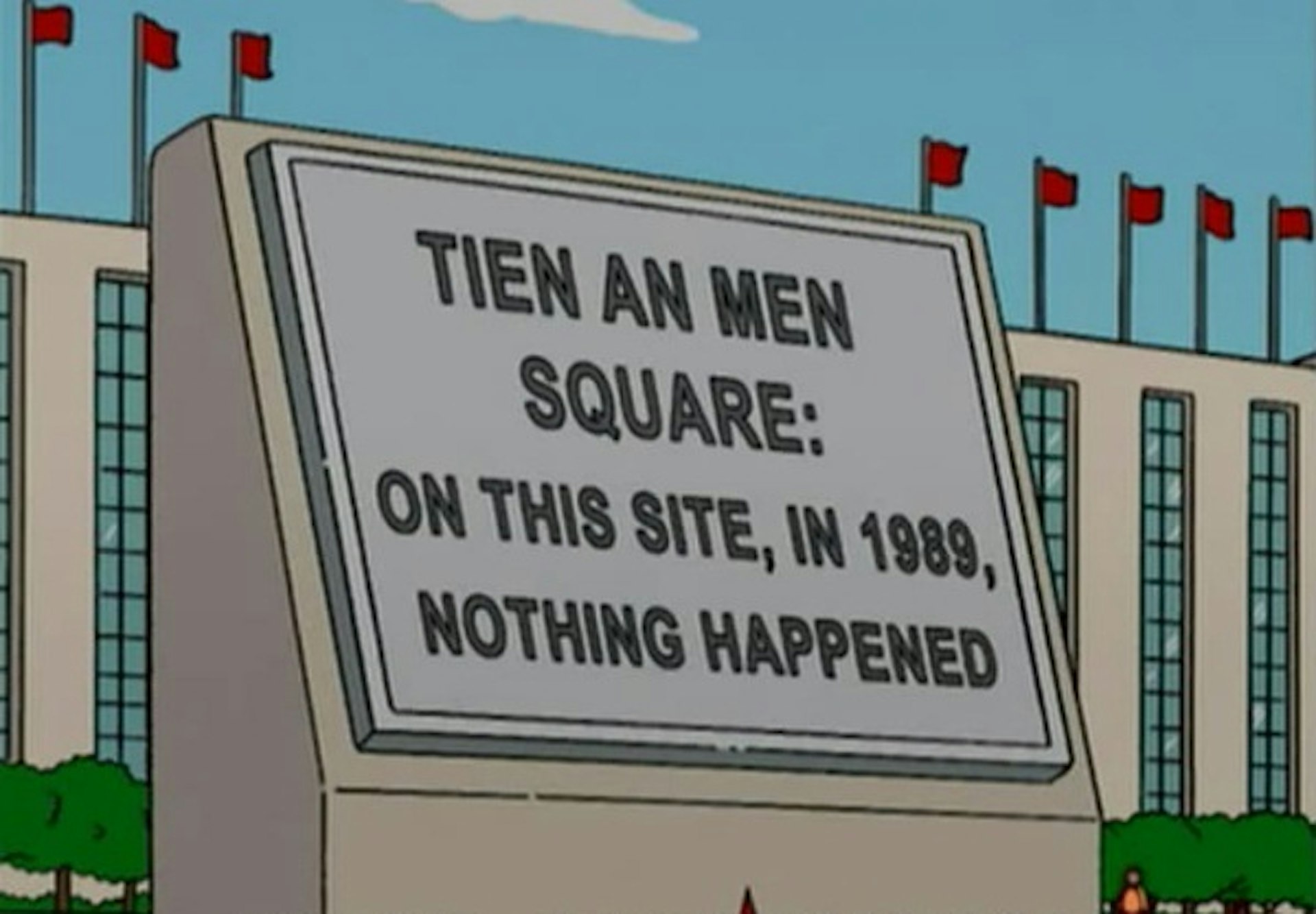

Simpsons did it

One certainty, though, is that the Tinananmen Square protests have been stricken from the record to the best of the Chinese government’s ability. With last week marking the 26th anniversary of the events, the party line was broken ever so slightly, though. This weekend, the English edition of the Global Times – one of the Communist Party’s official mouthpieces – quoted a Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson’s response to international calls to lift censorship restrictions: “Keeping quiet in public places about the 1989 turmoil has been accepted by the public as a political strategy to maintain social unity.”

One simple representation that captures this whitewashing stems from an experiment by Brooklyn-based artist Michael Mandiberg who, in 2009, decided to test the limits of cultural censorship from afar. He wrote to a collection of reproduction painters in Shenzhen’s Dafen Painting Village, asking them to reproduce Widener’s photograph.

The responses that Mandiberg received varied from the robotic to the remarkable. Some chose not to respond, some simply directed him to a payment site. “I was surprised by how transactional the whole thing was. The most common answer included some version of ‘Thank you for doing business with us,’ Mandiberg told us.

“Though I was curious about the unknowable absences… the painting studio that removed Tank Man, or the one that removed the man and the street lamp. Or the studios that never responded.”

Those absences are particularly jarring. Without the man at the front of the shot, Widener’s photograph is simply transformed into a celebration of military might, a standard Cultural Revolution-style propaganda piece. It’s particularly disconcerting when we consider that the man in the white shirt’s identity, whereabouts and welfare are still unknown.

And Mandiberg’s interest extended further than that: “One of my reflections a decade later is how all of them look like Thomas Kinkade paintings.” Kinkade – the McDonald’s of painters – was and still is one of the most commercially successful in the world, reflecting an idyllic, saccharine image of perfection in the American Dream. “These paintings end up reflecting many layers of cultural exchange.”

After artist Guo Jian’s struggles with Chinese authorities and eventual exile last year, this idea of a cultural conversation around protest movements remains essential, both in China and at home. Whether or not change occurs, reproduction will always play a key role in the 21st Century.