A personal trip through Turkey’s punk scene

- Text by Hannah Clugston

In Turkish “Arada” translates as “in between.” It’s a very fitting name for a film that follows a young man stuck between adolescence and adulthood, dreams and his father’s expectations, and traditional Turkish music and punk rock.

It also refers to Istanbul as a whole, a place that director Mu Tunc calls “undefinable.” Over Skype, Tunc attempts to put the city into words: “You can’t call it western and you can’t call it eastern. I never noticed this feeling until I lived abroad and then I understood that in Istanbul there is an overload of information and culture from east and west. If you walk down the street, you might see buildings from the Roman empire and on another street the Ottoman empire. The contrast is too much – it’s not like a blend of cultures – everything is black and white.”

Tunc’s first feature film is about what happens when these cultures collide. Tunc grew up in a household with a father who was a singer in the Turkish music industry, and a brother who was a significant player in Istanbul’s ’90s punk scene. Arada tells their story, exploring what it means to grow up in Istanbul and what happens when punk meets tradition. Nine years his senior, Tunc’s brother had a huge influence on him, and Tunc laughs as he recounts how he spent his Muslim festival gift money on albums by Hole and Underworld.

Although their punk days might be over, Tunc still embodies the DIY spirit often associated with the movement. His attention is now directed towards filmmaking and he hopes to usher in a new age of Turkish production where he can bridge the gap between cultural exploration and entertainment. This cinematic wonder is a good start, and he speaks to Huck about being a punk in ’90s Istanbul.

What was it like growing up in Istanbul, with all these colliding cultures?

It was strange. When I say that my brother was one of the first people to create a punk record in Turkey people think it sounds cool. However, when I was growing up, being a punk wasn’t cool at all. I had a hard time because I was listening to all these punk records but I couldn’t even speak to my friends about it – they didn’t get it. I had a cultural clash within me, so at home I was consuming all the same things kids in London consume. But, when I went to my high school – which was a private school with rich kids – they thought I was very strange because I wore Converse. This was before the internet, and even now, you couldn’t have a conversation with someone in Turkey about the Human League or The Smiths. So, when I was younger I felt weird and like an outsider.

Do you think you were like that because of your older brother?

Yeah, but also because my father was a musician too, so art and music were in our family. Even though my father’s music was completely different (it was Turkish art music), that idea of putting effort into art was at the core of our family. My brother found his own expression in punk, but then when I got older I realised it was causing arguments because my father didn’t want him to become a musician because he thought he’d not become rich and be able to live his life. So, I always saw my rebellious brother having to fight for his own values and tastes, which encouraged me to become a person that follows my own instincts too. Punk music also gave me the idea to “do it myself” and “do whatever you want” which was an important spirit to get hold of at an early age.

Photography: Onur Tekin

In the film, the father says: “The music you are playing isn’t right for this country.” What does he mean?

This argument happened all the time in my family. My father thought my brother was making English music and he said: “you are in Turkey, you need to make Turkish music.” This weird idea is still going on in Turkey – the idea that you need to do something for this country, not internationally. It’ll sound strange because if you’ve grown up in Britain and made a film, obviously you’d want to screen it outside of your country. But this idea is brand new in Turkey, it has taken 10 to 15 years to develop.

In the record store scene, there is a discussion about how the political coup has affected the music industry. Can you explain a bit more about this?

In the ’60s and ’70s, Turkish music was gold. Right now, people in UK dance music or in Seattle in the US are listening to these psychedelic Turkish bands and remixing them. But, every 10 years there was a coup in Turkey by the Army, and every time this happened parts of culture were killed in the process. So, these psychedelic musicians who managed to create a hybrid of western and Turkish music were destroyed after the coup. They couldn’t find space to play. And this happened in the film industry too. In the ’80s – after the coup – the only work was in porn. I know this sounds weird, but for three or four years all the big actors were in porn movies because there was no work in normal films. Culture in Turkey is always connected with politics.

Was punk a way of mobilising people against the government?

Not at all. What they were trying to do was to be part of a global movement. I think they were becoming human by listening to punk and understanding their place in the world. For example, my brother always used to speak to me about animal rights and becoming vegan – so these ideas were already given to me when I was little through the bands we listened to. I learnt all about not using consumerist products and global warming through punk records. Listening to these songs was like being on the internet for my brother, he picked up lots of information. So, the music is not just about being political but about releasing how to live with meaning. Through the music, they were trying to find their own voices.

At a party in the film, an artist says: “The whole art scene in Istanbul is just groups. One group is protecting this wall, and the other group is protecting that wall.” Is that still true of creatives in Istanbul now?

Yes and it’s a really big problem. I think whenever you find any specific communities around culture – like punk or indie film – members of the group very often don’t actually want their communities to grow. They always say “nobody understands me”, but in reality, they don’t want to be understood because then it becomes pop culture and then they’ve sold out. But I think that’s really damaging to culture. I think if you protect your community too much you prevent other people from understanding it. For example, if avant-garde cinema continues to get smaller and smaller, soon everyone will just be watching Spiderman. The minute you think you are protecting something you are destroying it at the same time. I’d love to create films where we can bridge the gap between cultural information and entertainment. People like Spike Lee, Richard Linklater and John Cusack don’t exist in eastern cinema, so it’s important to try and start something new.

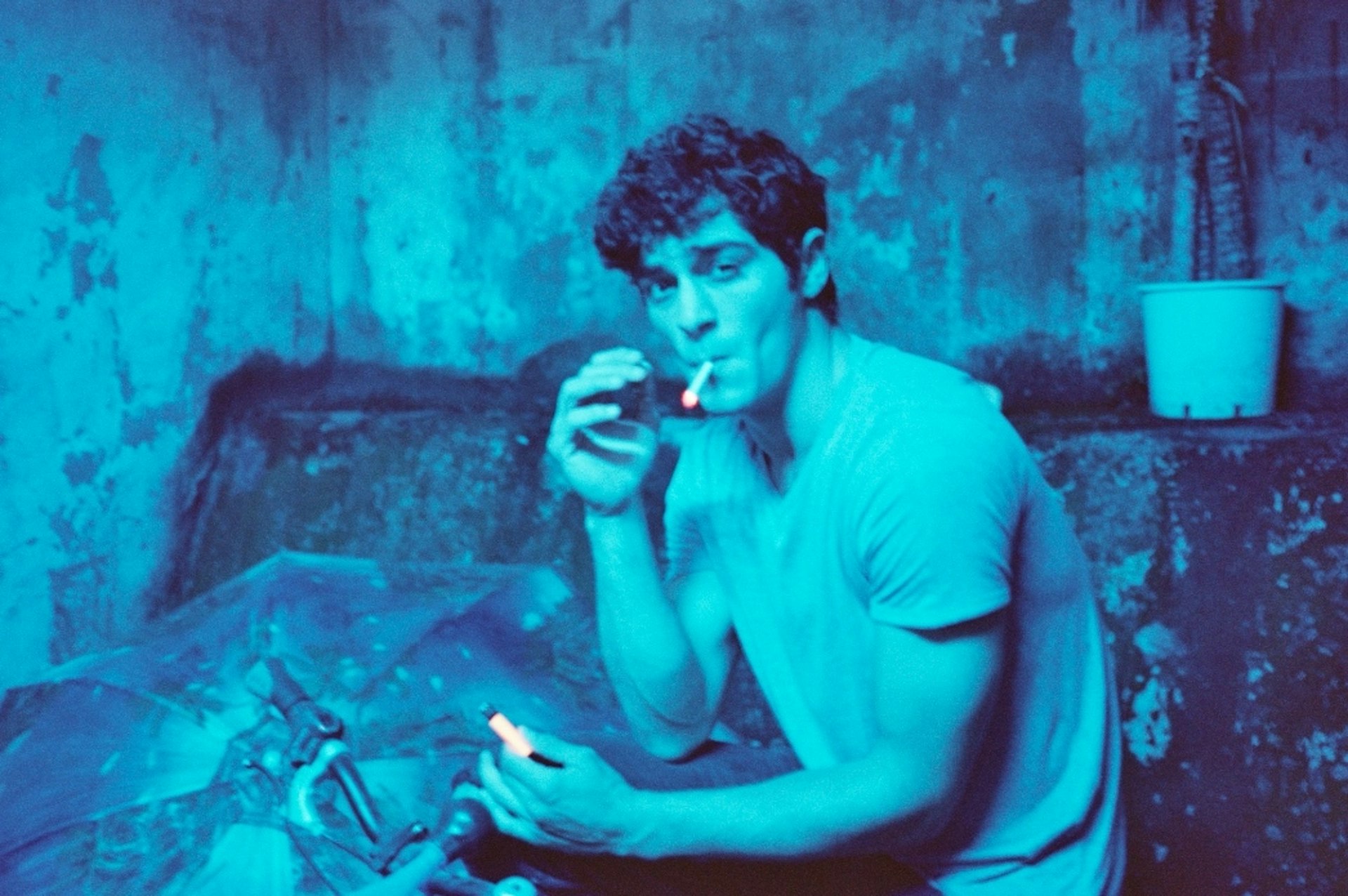

Mu Tunc’s actual brother in his band, Violent Pop

Mu Tunc’s actual brother in his band, Violent Pop

Obviously, this is an immensely personal project – how did you find the process of making the film and have your family seen it?

Until I started production my family didn’t know about it – not even my brother. I didn’t show the movie to my father until it was finished. It wasn’t easy. The song you hear in the film is my father’s, and I had to buy the rights to his songs, which was hard without any help.

The film was a gift to my father. He was a musician, but he couldn’t continue because my brother was born and he needed to raise his family, so he chose a safe job as an industrial engineer. However, as he got older I saw resentment rising up because he hadn’t lived the life he wanted to. So, I wanted to gift him the film to show how important he was in my life. Before I made the movie, I was living a safe life too. I worked all over Europe and had a job people in Istanbul would kill for, but I wasn’t happy in myself. I was overweight and I realised afterwards that I hated myself. You really need to do what you want to do. If you don’t do it – no matter what – that thing will come up and get you even if you are 50 or 60-years-old. It’s like a horror movie that you can’t run away from. It’s beyond important because I saw it in my own family – my dad was a perfect guy but then he started to become one of the most unreasonable people you’d ever meet. He is not unreasonable, it’s just that he lived a life he didn’t want to – he is a musician.

Arada will have its UK premiere on 1 October at Sensoria Festival in Sheffield.

Follow Hannah Clugston on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.