Emerging Directors of the Caméra d'Or

- Text by Sophie Monks Kaufman

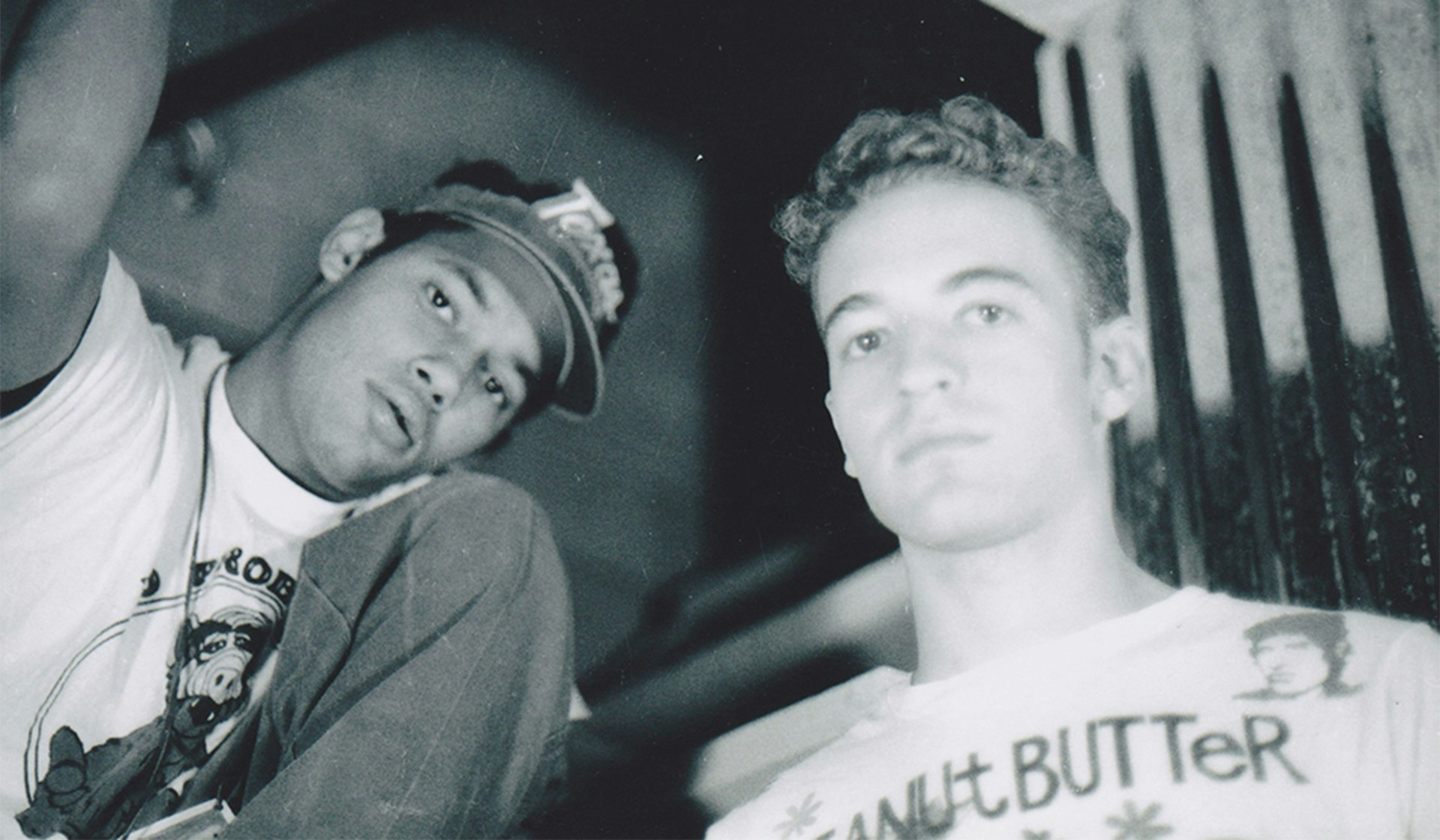

- Photography by Lost River

Cannes swiftly becomes a self-contained universe. The routine of rolling down the hill to The Croisette early in the morning becomes ingrained. Festival housemates become like family and the whole industry circles the same orbit: waving badges at beige security men, trotting up endless stairs, frowning in the wifi café, queuing for espressos.

Twitter is the newswire. It’s hard to choose what to see amid contrasting recommendations. Everything is someone’s ‘masterpiece’ while that same work was ‘hated’ elsewhere. Critical buzz ceases to mean much as lack of sleep and subjectivity reaches a fever pitch.

But just as life here becomes normality, it comes to an end! This is the last of our Huck reports on emerging directors of the Caméra d’Or. To contrast with the previous female-dominated update this one is something of a sausage-fest.

Run

Run

The first film to be selected for Cannes from the Ivory Coast has more symbolic importance than stone-cold brilliance. Philippe Lacôte’s drama has the country’s civil war as a backdrop to the trials of the lead character, instructively named ‘Run’. If Run had a theme song it would be The Clash’s ‘Should I Stay or Should I Go’ with the added conclusion: “I should definitely go “. Catch Me If You Can’s Frank Abagnale would relate to a life that has gone: get into trouble then run away.

The film flashes from a present in which Run has just bumped off the president and the past life that lead him to assassin’s row. A stand-out segment involves a young Run teaming up with ‘Greedy Gladys,’ a professional eater whose sessions make Stand By Me’s pie-gorging scene look like a famine. Gladys is a joy to behold: a sanguine, sensual sensation with limited expectations for what life can dish out beyond the meal table.

It is when the narrative loses Gladys that it loses its vitality, running aground in detailed subplots involving a group called The Young Patriots and their short-tempered leader. Money and women and friends come and go and by the time Run decides to make a stand the impact of this personally significant changed momentum is barely registered.

Snow in Paradise

Snow in Paradise

The label ‘British gangster film’ may be a turn on for some and a turn off for others but the thing about Snow in Paradise is that it’s not just a British gangster film. Its social ideas, the concerns of its hero and the woozy sequences expressing a fall out with reality mean that editor-turned-director Andrew Hulme has given us a progressive reinvention of a tired genre.

Dave (Frederick Schmidt, who debuted this year with a small role in Starred Up) has been born into an east London crime family. It’s the present day and this means that he has to deal with hipsters. The opening is comic. He and a mate peer through the window of a coffee-shop at punters who refuse to meet their eyes “Look at them!” says Dave contemptuously. Hulme cuts to an interior of gormless people frozen in the glow of their Mac lights. Dave is excited to be en route to his first real job for his Uncle Jimmy (Martin Askew) and he is bringing along a mate, Tariq (Aymen Hamdochi): a nice Islamic kid whose only crimes are his adorably ridiculous rap rhymes.

At this stage feels like it could be a spirited take on the tried-and-tested, coming-of-age in a gangster-family story: Goodfellas in East London. But Hulme has other ideas and they’re big.

It swiftly becomes apparent that not only is David out of his depth but that his inclinations are not clinical enough for the family business. Uncle Jimmy is a calmly-spoken psychopath devoted to doing business the ‘proper’ way. There exists a philosophical counterpoint in his uncle’s rival, Micky, who courts David because of an attachment to his MIA dad. Micky (David Spinx) may be vocationally illegal but he is seemingly committed to being that way peacefully. As an increasingly distressed Dave flounders between family loyalty and his own moral code, the film begins to ask spiritual questions in the gangster Gandhi vein. Can a peaceful temperament ever defeat a violent one?

There’s another layer of social intrigue in the form of the Islamic temple that Dave initially enters in search of Tariq. As life’s storms become increasingly intense, emphasised with an oppressive, Animal Kingdom-like score, the temple becomes – along with an unjudged drug habit – his escape. Hulme is admirably balanced in his depiction of religion. He is neither reverent (“You’re off your nut,” is an early response to the temple leader) nor irreverent. Hulme is equally restrained when it comes to showing the violence of the crime world. There’s a suitcase that carries the same meaning as a box in Se7en and we never see inside it. Equally David’s girlfriend’s profession is telegraphed in an elegant and elliptical scene.

As the central performer in virtually every scene Frederick Schmist is sympathetic and plausible as a soft soul in a hard body on a bad path. Themes take over from narrative tightness as a certain point but Dave’s dilemmas and the question of how they will resolve compels right to the very end.

Lost River

Lost River

Ryan Gosling has the jump on most first-time directors by virtue of being Ryan Gosling. The affectionate position the musclebound Canadian actor has within the public consciousness means you want to like his work. It’s Ryan Gosling!

Lost River‘s world is composed of fantastical images that scan like a visual montage of Gosling’s creative influences. The lawless dystopia where Billy (Christina Hendricks) is trying to keep her head out of the murk has the desolate atmosphere of Harmony Korine’s Gummo. Her son Bones (Iain De Caestecker)’s quiet relationship with the rat-owning girl nextdoor (Saorsie Ronan) conjures up Donnie Darko. Because this is a dreamworld, Gosling has license to put whatever he wants on screen: houses burning apropos of nothing, red-filtered ‘entertainment’ bars where beautiful women pretend to die. Bully (Matt Smith) and his deformed buddy Face cruise the ‘hood in a car with a blue velvet throne protruding from the back. Who could that be a nod to?!

What all this shows is that Gosling has good taste when it comes to influences. And good taste when it comes to actors. The cast are wonderful and, in particular, Ben Mendelsohn, Saorsie Ronan and Christina Hendricks can add another flawless outing to the resume. What Lost River mainly shows is that a film can be entertaining without being remotely eligible for the description of ‘good’ . In this self-conscious, plotless, mash-up of his mind’s eye, Gosling has established that his status as a director is profoundly different to his status as an actor. Let’s see if he uses those muscles to work up a coherent film next time.

All Cannes prizes including the Caméra d’Or results are announced on Saturday 24 May. Check the official festival website to identify the victors!