Halston: a tale of how big business devours creativity

- Text by Colin Crummy

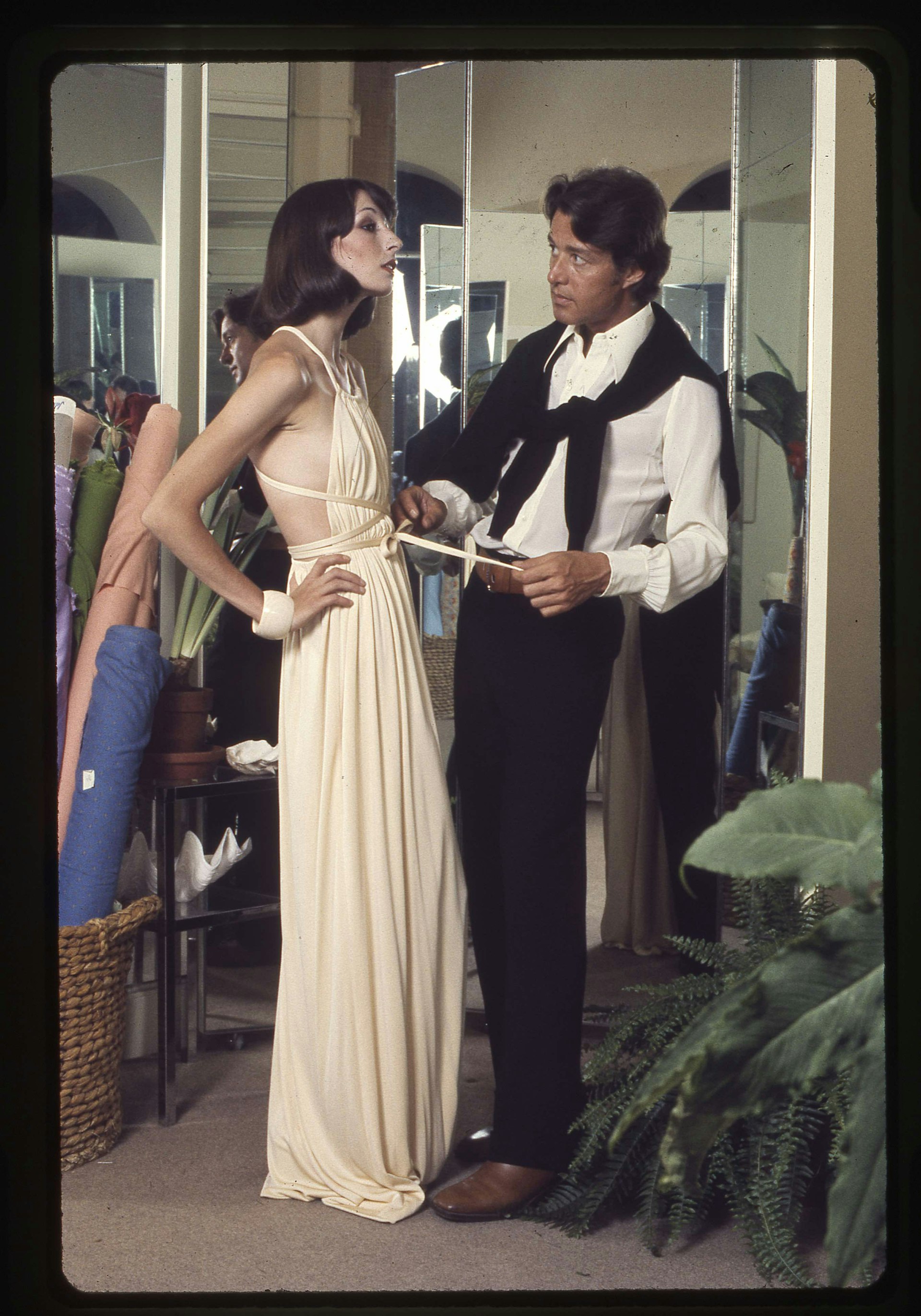

- Photography by Dogwoof

Roy Halston Frowick was a very modern fashion designer. In the 1970s, the American became a surname-only superstar with his own fragrance, celebrity endorsements (from Jack Onassis to his friend Liza Minnelli), and a reputation for cultural innovation. His minimalist fashion liberated women from constrictive couture, and his catwalk gang, the Halstonettes, included BAME and plus size models.

Halston also harnessed the financial might of big business to realise his ambitions, and became the first designer to have his trademarks bought by a corporation. He had 30 licensing deals by the late ’70s, and was the first high-end designer to create a line with a mass retailer, JC Penney. Unfortunately, this commercial clout came at a price.

Halston is a new documentary that shares this part of the designer’s story. Told in the style of a corporate thriller, it relays the conflict between the artist and the ‘money men’, as Halston’s brand and name were sold on to increasingly unsympathetic corporations, which eventually ousted him and sold off his work at discount prices.

The result is a very modern cautionary tale about the clash of creativity and commerce – and it’s one which Halston director Frédéric Tcheng, the French-born filmmaker who made the Raf Simons documentary Dior and I, understands all too well himself. We caught with him on Skype to find out more about the project, and the increasingly relevant messages that lies behind it.

What did you know about Halston before the documentary?

I didn’t know that much about him. His name became synonymous with Studio 54, just like Bianca Jagger and Liza Minnelli and Andy Warhol. At one point the press referred to them simply by ‘Andy-Bianca-Liza-Halston’. They were in the newspapers every day, which made him a household name but overshadowed everything else about him.

But you were drawn to his story because of the business aspect?

Absolutely, I really related to the business conflict he had to go through. As a creative person, you feel when you’re dealing with an industry that is often trying to exploit you and extract something out of you – sometimes it can be very traumatic. After working on several documentaries and having been in these sort of situations, I saw this film as an opportunity to talk about these issues and reflect on my own place as an artist within the system.

How has that conflict manifested for you?

It usually has to do with the final cut. I’ve worked with big corporations in the past and sometimes it’s very hard to get your vision across when people are not really interested in making films, and more interested in making money.

How did you navigate that?

You need to have very good lawyers. In France, I’ve been pretty lucky because the artist has a special status in France. Their work is protected so that in film, for example, the director always has final cut. That’s very different to how it is here in the US, where it’s the jungle. You need to be very prepared and at the same time understand there’s always risk involved. Because you care about the product, you’re very vulnerable: it’s your name on the door, and that’s something Halston would say all the time. I know exactly how he felt because it’s my name on the picture and you are willing to do everything it takes to make the best film – sometimes that means going against your interest, or cutting your salary, for example. The industry knows that and exploits that.

Halston was ahead of his time in terms of inclusivity and diversity. How do you think he saw it?

He was part of a generation growing up in the ’60s during the civil rights movement. There were designers of colour like Stephen Burrows, who he was very close to. So Halston was, as we would say today, very woke – but it was just natural to him. We asked the models [who are interviewed in Halston] and they said he never talked about, he just did it.

Was he naïve in his business dealings?

He was a positive person. He saw a great opportunity – and it was a great opportunity. [But] he got bought out by a big corporation. He was the first designer to enter the big corporate game, and now everyone’s part of a corporation. It’s almost impossible for a fashion designer to survive without being part of one. He took that opportunity and it worked like a charm for 10 years. He became a superstar; he had dozens of licences, he lived in this incredible house and had the most beautiful showroom in the world. Should he have said no in 1973 to the corporation? Absolutely not.

Why has he been written out of fashion history?

For many reasons but the brand didn’t survive him. It was like YSL and Chanel at that time. The corporation squeezed the life out of Halston, in my opinion, until he died. After that, it never lived again. You can’t have a legacy without corporate interests, unfortunately, working on that legacy and making sure it’s out there. The other part is they divested the archive and erased the video archive. They erased the legacy.

What’s the lesson to take away for people in these industries now?

I hope it’s a positive lesson. Halston was not afraid to take risks and do things that hadn’t been done before. For the most part, it worked really well for him, and towards the end it backfired. There was a perfect storm. But that doesn’t mean what he did wasn’t groundbreaking or that we shouldn’t take risks, play all your cards, and think about what you can bring to the game – it’s what he was about.

Halston is in cinemas and streaming now.

Follow Colin Crummy on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.