Identical Strangers: the secret triplets that stunned the world

- Text by Thomas Curry

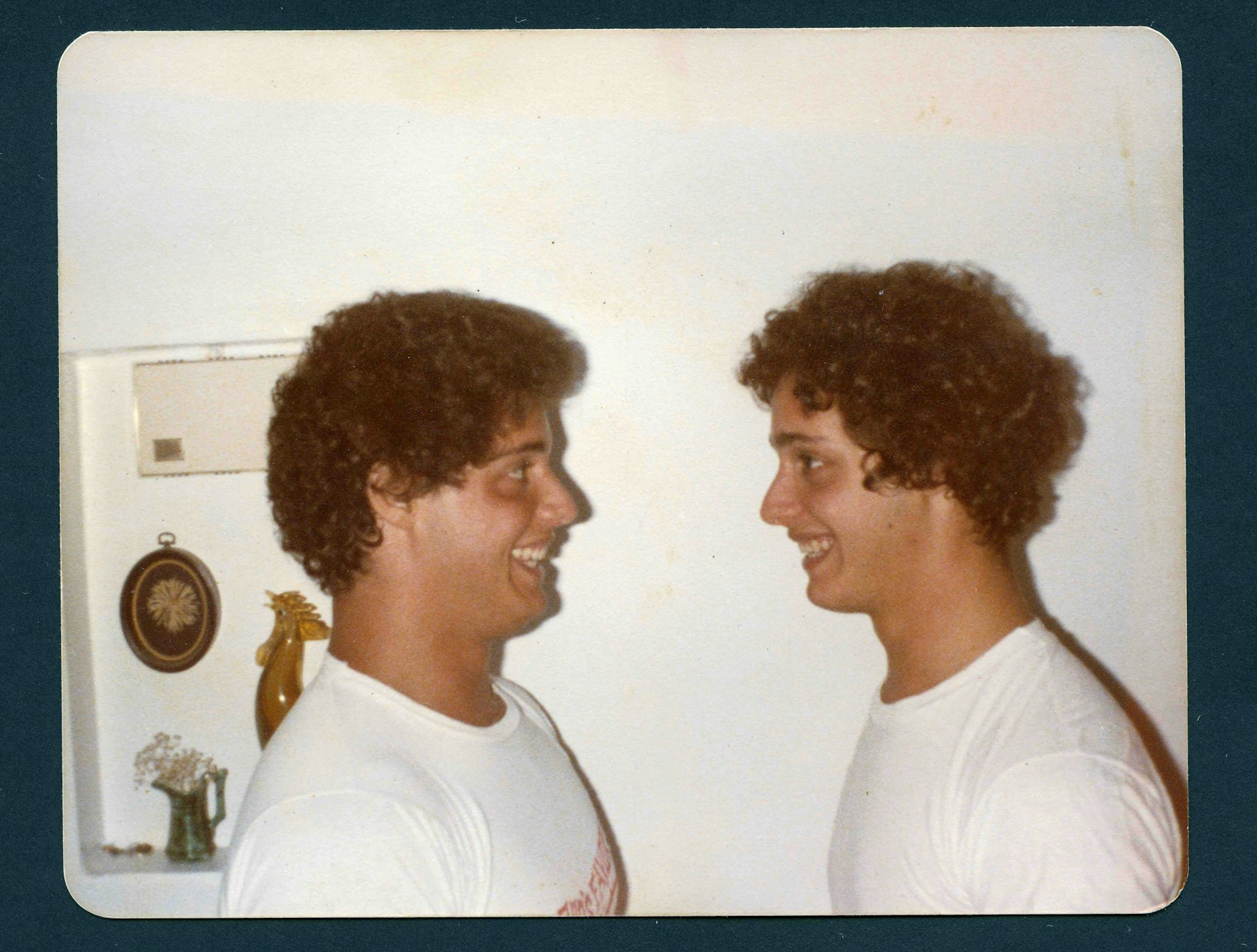

Robert Shafran’s first day of college in 1980 got off to a peculiar start. Classmates he’d never met kept calling out to him, welcoming ‘Eddie’ back to school, as if greeting an old friend.

When Eddie’s slightly bemused roommate – who knew that Eddie hadn’t planned to return to class that year – found Robert, he was stunned. While certain that the man standing in front of him wasn’t Edward Galland, he was the spitting image of his absent friend. The hair, the eyes, the nose and the mouth were indistinguishable. After a frantic drive to Eddie’s house, the two men, newly reunited, soon realised that they were, in fact, identical twins.

But when the story ran in the New York Post, and another 19-year-old, David Kellman, realised he was their triplet, the story went from a happy accident to an unthinkable coincidence. After their reunion, the three brothers became an instant media sensation, interviewed by Tom Brokaw and Phil Donahue, clubbing at Studio 54, even appearing in a movie with Madonna. But as their notoriety increased, so did a central question – how did the brothers come to be separated in the first place?

Determined to unearth the truth behind the events that tore them apart Three Identical Strangers is a gripping, heartfelt endeavour to answer that very question. Equal parts conspiracy thriller, family drama and philosophical mind-bender, the film explores questions of free will, nature vs nurture, and how we understand identity. Ahead of the film’s release this Friday, we spoke to director Tim Wardle about what it was like to work on the most extraordinary documentary of the year (spoilers ahead).

What prompted you to investigate this story now?

It was about six years ago that a producer called Grace Hughes Howard brought the idea to a company I was working at. Instantly, you recognise that it’s an extraordinary story: it’s incredibly human, almost tabloid-like, about these triplets being separated, reunited, then separating again. But more than that, it enabled you to ask all these bigger, philosophical questions about nature vs nurture, free will, the nature of family and destiny. That really appealed to me. I studied psychology at university, I’m one of three brothers, my wife is Jewish, I felt like I had a real connection to it. The story of the triplets is a universal story about what makes us who we are.

Do you think it was only possible to tell this story because it largely took place during a pre-internet age?

It’s part of a diminishing pool of stories from this pre-internet era where the people involved can still give first-person testimony. When you get an idea like this, you think: why has no one done this before? But we quickly found that lots of people had started to try and work on it. We learned of three attempts by major US networks – two in the ’80s and one in the ’90s – to do a story about not just the triplets, but the whole investigation. In every case, the film was pulled by people higher up in the network. There were all these conspiracy theories about why this story hadn’t been told before and a lot of people who warned us that we’d never get this film finished. There was a very real sense that very powerful people in all sorts of organisations had been suppressing the story for many years, but I think the passage of time has helped us. Some of the people responsible for suppressing it have passed away and the media has become more fragmented, so any connections they might have had, particularly east coast media in the US, are not as powerful as they were before.

Why do you think it is that our culture is so fascinated by identical twins and triplets? In the same way we’re drawn to crime stories because it allows us to flirt with the idea of danger, do you think we’re drawn to these stories because it allows us to flirt with the possibility that we’re not unique, not individual?

In some cultures, twins are revered as demi-gods, and in other cultures, they’re murdered because people see them as aberrations. We like to question, what would it be like if you had another life? If you’d made another decision? There’s an escapist fantasy to it: what if I’d married someone else? What if I’d taken another job? People are interested in the multiverse, those alternative possibilities. It taps into something I think we all wonder about subconsciously; how much control do I have over my life? How much am I not a unique individual?

Most people like to think they have agency over their lives, but the thing identical twins points towards is that is that we don’t have as much control as we think we do. Biologically, so much of our body and our behaviour is determined. We all want to believe that we’re free and that we make our own decisions, but these twins tell us the opposite. Maybe there’s a recognition on a base, subconscious level that we don’t have as much control as we think – and that’s why we’re drawn to these stories.

Would you say that this is a film about free will?

Absolutely. I think it’s about what makes us who we are. Were we shaped into what we are today or were we just born this way? Free will is an inherent part of that. Working on the film, it was quite shocking to see how strong genetics and our biology are in determining who we are. The scientists making this, when they split the triplets up, they absolutely believed that the environment was 90 per cent of who we are: kids were blank slates, and it’s down to parents. The study confounded a lot of that. Genes and biology are a significant part of who we are: 50 per cent, if not more.

On an intellectual level, I can see why the psychologists wanted to investigate this topic, but why would the adoption agency agree?

In the 50s and 60s it was a wild west for psychology, you had all these experiments which would never be countenanced today, they’d never get past an ethics committee, so the historical context is important. Having said that, we’ve spoken to a lot of people at the agency who were totally against it at the time, no other adoption agency would take part, despite being approached by Peter Neubauer, so the idea that no one was saying this is not a good idea is just not true. I think ego was a huge part of it too; when you get people trying to push the envelope, to definitively prove if we’re shaped by nature or nurture, I think you’d have been one of the most famous psychologists in the world. I’ve no doubt that was a huge factor in this.

How do you think someone could go about making amends for the tests that have been done on these twins?

It’s a good question. ultimately I think it’s a question for the brothers and those who were part of the experiment. I think the main thing they want, is for the data to be made available to them. Nothing from this study has been seen, it’s all under wraps. There’s been a lot of debate about whether material gathered by unethical means should still be used. I think the brothers want an apology. They got a sort of apology after the film came out, but there hasn’t been a big public apology.

What do you want viewers to take away from the film?

I want them to feel a rollercoaster of emotions. It’s very deliberately told with the same chronology as the brothers found out about it. That’s why it feels like it has these amazing twists. I want people to feel different emotions, and to think about the fundamental issues that the film is discussing – do we have free will? What makes us who we are? What is the role of nature vs nurture? What is the nature of family? How is power abused and how easily can those abuses happen? I felt quite conscious of the similarities in power dynamics between the scientists and my role as a documentary maker, you control your subject – put a camera in front of someone and they’ll tell you almost anything, then you have to edit that together into a film. That’s a huge responsibility. I hope people think about that power imbalance. I don’t think it’d ever happen in psychology today, but there are other areas of science – genetics, AI or neuroscience, where researchers are crossing boundaries because it’s a new frontier, the rules aren’t set, we haven’t realised yet, but we might look back and think, that shouldn’t have been done. I didn’t want to make something just about issues, I also wanted to make it entertaining but to use that packaging to explore deeper issues. It makes those thematic ideas more palatable.

Do you ever think you’ll work on a story like this again?

I’ve had to reconcile myself to the fact that I’m unlikely to work on something like this ever again. I remember during my first week, my editor, he watched the rushes, and by about day four, he turned to me and said, we’re never going to work on a story like this again in our lives. He was definitely right. I think you have to make peace with that.

Three Identical Strangers is in cinemas nationwide from 30th November.

Follow Thomas Curry on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.