London skateboarders on masculinity and mental health

- Text by Beth Webb

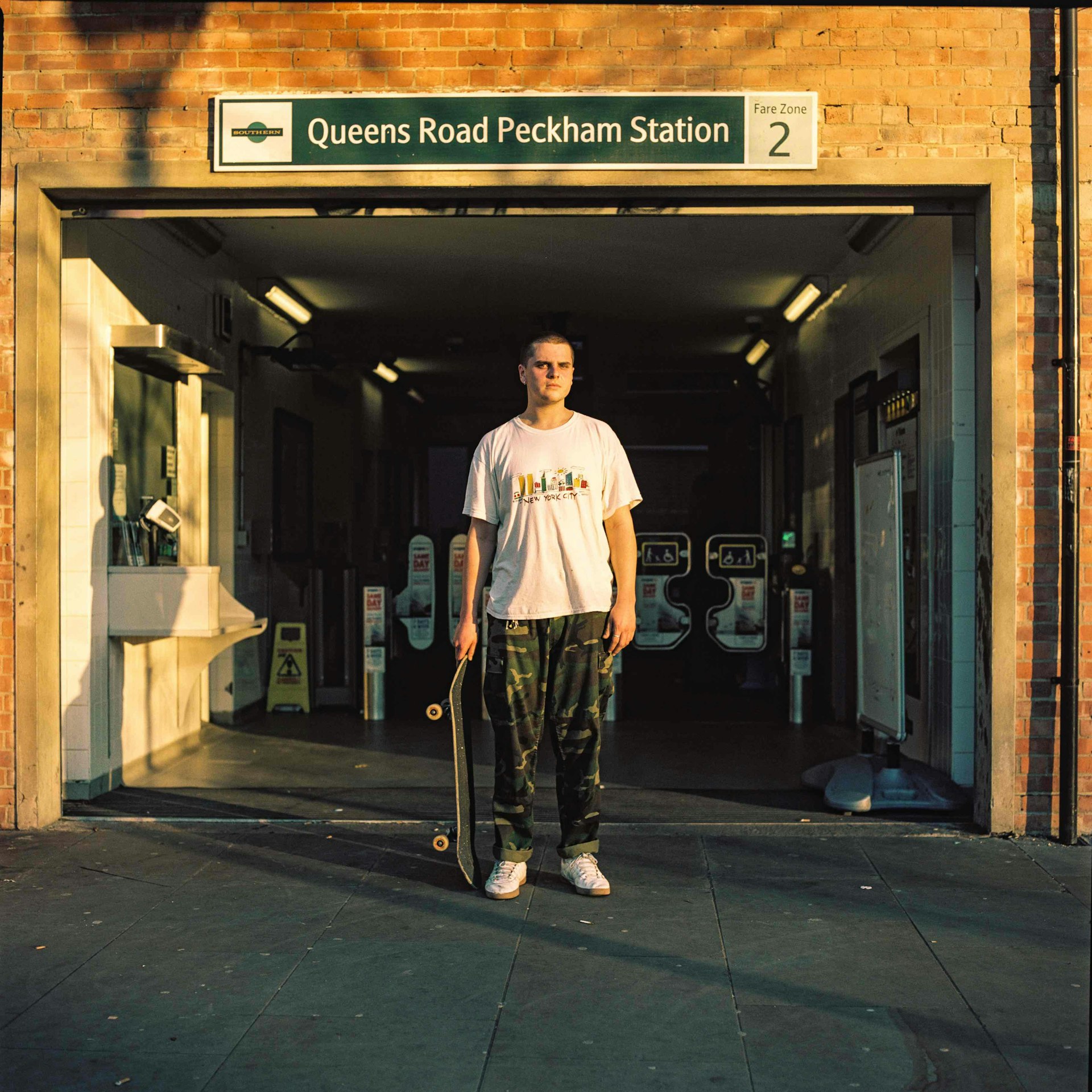

- Photography by Theo McInnes

Minding The Gap is the sort of film that speaks for and to an entire generation. Set in Rockford, Illinois, the Oscar-nominated documentary all at once embodies the catharsis of skateboarding, the caustic waves of intergenerational violence, and the importance of community in an area rife with poverty and unemployment, told through the stories of director Bing Liu and friends Zack Mulligan and Keire Johnson.

Huck sent skateboarding collective I Should Not Be Here to see the film and share their reactions. A creative group that resides in South London, the boys put out zines, videos and music that reflect their common bond over the sport.

On a warm day outside London’s Queens Road Peckham station (their favourite skateboarding spot), they unpacked the key themes of the film.

On masculinity

Pete Lobas, 29: Something that Zack said in the movie really resonated with me: that when you’re young, you’re told that you have to be this tough, strong guy. Hide your emotions, work through it, this whole “boys don’t cry” mentality, which is really shitty. I hope that parents and people outside of the skateboarding community see this documentary and see that this is what most young men are told, and that it’s not right.

Adam Connett, 30: The state of modern skateboarding is really disingenuous, like where the fashion industry is trying to bleed it dry because it’s so popular at the moment. This film feels genuine, and shows a real vulnerability. I think it’s something that all of us can connect with.

Peter Rudd, 33: I look at traditional sports and that idea of the macho man. I didn’t want any part of that. Skateboarding is whatever you want it to be: it’s a creative outlet, it’s a way to release tension, and it’s not defined by anything else. It’s just a set of curbs – it can be anywhere or anything you want it to be.

On mental health

AC: It really comes across in the movie how cathartic skateboarding can be; that it can help you work through serious issues, or it can be a fantasy that you can just drift into. We’ve all dealt with mental health problems either directly or indirectly, and through skateboarding you form this really nice support group. Your parents, girlfriends, boyfriends, whoever, aren’t necessarily who you want to approach about these things. The people that you skateboard with on a sunny day are the people that you engage with the most.

PL: It’s that aspect of finding a new family, and finding yourself more comfortable with those people than with your immediate family. I felt that watching this film. When your parents don’t understand what you’re doing; you try to explain it to them but they don’t even try to understand it. That’s very hard to deal with. It pushes those boundaries further, so you try to escape even more. You get a different family through skateboarding. It’s one of the best feelings you can find that’s for sure.

PR: We all try to look out for each other as best we can, and I feel like with the director, his way of looking out for people was to make this film. It was a story that he had to tell, not that he wanted to tell…

AC: …Like when he went into having this really fucking raw conversation with his mum, and how he waited to do it on camera.

PR: When the film’s life begins like 10 years previously, people weren’t talking about mental health in the same way that they are now. I know that with the guys here we can have honest conversations about mental health that we couldn’t have in the past. It just wasn’t a prevalent conversation, and it’s refreshing to see something like this film put out from the community that’s honest about that.

On politics

AC: We can all resonate with Keire in the film who went from his pot washer job to front of house. You don’t get paid anything, you don’t get any respect. We’ve all worked shitty jobs that pay minimum wage or we’ve been laid off – I got made redundant and wasn’t in work for four months. It was fortunately during summer so I was just skating every day when I wasn’t applying for jobs. The current situation here is pretty dark and fucked at the moment. Nothing’s certain, everything’s divided.

PR: When I first moved to London it was a struggle. I was living above a pub with no central heating. But in a world that feels very dog eat dog at the moment, I think skateboarders buck that trend.

AC: I love skateboarding because it’s not elitist. You see some kids at the park and their boards are basically a two-by-four that’s waterlogged but they’d still rip around the park. Often, those guys are the best.

On skateboarding

PR: I think because the filmmaker comes from within the community, the film shows a snapshot that’s quite often missed. Skateboarding today is just seen as this thing that’s cool; it’s been appropriated and you don’t really get that same level of connection – like there are all these Instagram accounts that take the piss out of the way that fashion uses skateboarding, for example. I think this film resonates with the wider skateboarding community.

PL: For me, completely changing my life – dropping everything in Canada and moving to London – even though I knew that I was moving here without knowing a soul, I knew that I would be fine because I skateboard. Meeting these guys was one of the best things that ever happened to me.

AC: Skateboarding’s always been a bit of a proving ground, and it’s got a history of just being white angry boys. It’s now becoming more progressive – we’re seeing a lot of girls, a lot of people from all different types of backgrounds coming forward to skate. For me, that’s what’s really cool about skateboarding: it doesn’t matter what your background is, what your ethnicity or your gender is, as long as you like skateboarding. The only problem anyone ever has is with posers. People who walked around with a skateboard but didn’t skate, not the kid who couldn’t afford a board or the kid whose shoes are falling apart.

Ben Harding, 29: It’s interesting that our group’s age range is 19 to 35, but it doesn’t feel like anyone’s any different. Everyone comes from all over the country and beyond.

AC: There’s this rebellious streak in skateboarding that we all carry in us. We’re around 30, we’ve got partners, jobs, responsibilities. One day we’ll have families, but we’ve always got this rebellious little “fuck you” streak in us still. It won’t die.

Minding The Gap is released in the UK on 22nd March.

See more of Theo McInnes’s work on his official website, or follow him on Instagram.

Follow Beth Webb on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.