Marianne Ihlen: the woman and muse behind Leonard Cohen

- Text by Daniel Dylan Wray

Over the years, British documentarian Nick Broomfield has made films on a wealth of subjects; from nationalism in South Africa to tracking down Sarah Palin.

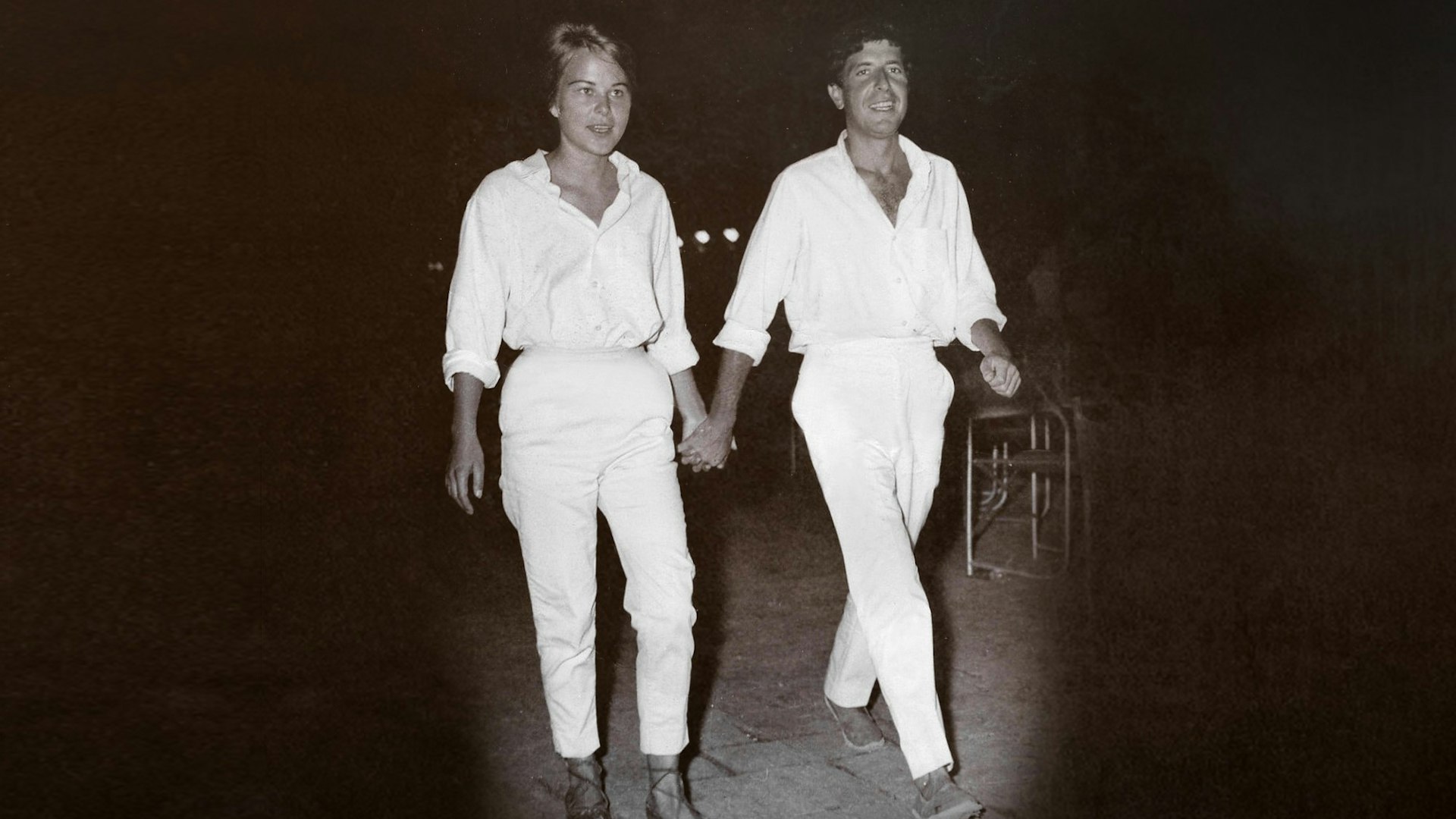

But alongside this deeply eclectic choice of film subjects sits a number of music documentaries. These have explored the murders of Biggie Smalls and Tupac Shakur (Biggie & Tupac), the death of Kurt Cobain (Kurt and Courtney), and the life of Whitney Houston (Whitney: Can I Be Me). The latest is this year’s Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love, a film that explores the key early relationship between the late songwriter Leonard Cohen and his one-time romantic partner and often described muse, Marianne Ihlen, who Cohen wrote the greatly adored song “So Long, Marianne” about.

The story came back into focus in 2016, when a touching letter Cohen wrote to Ihlen on her deathbed went viral just months before the singer passed away himself. This was an impetus for Broomfield to further explore the pair’s relationship, and Ihlen’s impact on Cohen.

Broomfield’s film focuses on the time the pair spent together on the Greek island of Hydra during the 1960s, before Cohen’s songwriting career took off. In a strange twist, it also transpires that Broomfield visited the island as a young man in 1968, and had his own romantic relationship with Ihlen.

After the film’s European premiere at CPH:DOX in Copenhagen, Broomfield took time out of editing another new film to speak about the documentary.

You’re in Words of Love because of your relationship with Marianne but you’re not on screen and barely use voiceover – was it important to try and remove yourself from this story as much as possible?

That was the hardest element to get right because it’s really their story. Hopefully, it’s a reflection of them rather than me. It was hard to get that tone right, that’s the bit I was continually re-writing to get to work. But that allowed me a lot of time to reconnect with them and a lot of mutual friends. They were surrounded by a lot of lovely people, who were a delight to meet, rather than the Whitney film where I met a lot of ghastly people who were all in it for the money and stuff. That really wasn’t the case here. There was a lot of love and admiration for Marianne and Leonard. They both lived their lives very honestly, so that was refreshing.

What did you learn?

I think the thing that struck me most about Leonard was his discipline. I think that’s how he survived living on that island – he had a real work ethic. I think part of the strength of Leonard’s work is he is honest about himself. He didn’t paint himself as a saint. I think he’s been painted a bit as one since he died but he was pretty honest about a lot of things in his life, which is what makes his writing so strong. Also there’s his humour, which is so constantly present in everything.

You and Leonard share a connection of benefiting artistically from meeting Marianne. How was she as a person?

She was so open and receptive and interested in people in a genuine and giving way. She was encouraging to so many people to realise their full creative being. It’s an oddly thankless task in that it’s not monetised: she had this incredible gift to access the real person and encourage them to throw away their doubts, fears and inhibitions. She was incredibly modest – an exceptional person.

How did she encourage people?

I think she really opened people up and allowed them to reveal themselves. She was really interested in people. She had that ability to really zone into people, and of course she did that with Leonard.

Where you a fan of Leonard when you were with Marianne?

I had never even heard of him. When I was on Hydra she played me his first album, which had just come out the year before. She was clearly still so in love with him and a bit tortured by it. He would often come into the conversation – he was such a big presence in that way.

You mentioned Marianne’s role as being a somewhat thankless one. Is that part of a problem with being cast as a muse? That you’re essentially facilitating the talents of others – usually a woman doing so for a man – to the detriment of your own talents and pursuits?

I remember her talking about how she felt inadequate because she was always surrounded by these very accomplished artists, painters and singers on Hydra. I think she felt that she didn’t really have a talent. I don’t think she felt it was in liberating and discovering other people. She was just very in the moment and had a mystical view of life and was on a search for some truth. I don’t know what the truth was, or if she ever found it. I think her and Leonard were both searching for that; it was of the time when people were looking for truths and answers.

Leonard spent years on Hydra and it is painted as a bit of a magical island and microcosm of counter-culture in the film – you took your first acid trip there – was it a special place?

Yeah, completely. The port was the centre of a volcano, so it was a completely volcanic island that had been thrown up. There were no cars, just the sounds of donkeys and roosters. There was a simplicity to the island that was intoxicating. It’s so beautiful. It was an epicentre, a place of learning; it felt like you were in the centre of the universe.

The island almost consumed Leonard. The film states he had a breakdown after writing his novel Beautiful Losers, which he wrote full of speed while fasting and hallucinating in the scorching heat. He said it took him 10 years to recover from that period of speed use. Did Marianne express concern about him during this period?

She didn’t speak about that but her previous husband was probably worse in that way. I think he took so much peyote that he never really recovered, so Leonard, if anything, was a tamer version.

Leonard, by his own admission in the film, was someone who very much took advantage of the free love era and had many partners. But he’s also quoted as saying, ‘I can’t wait until women take over’. How did you view his attitude towards women?

I think he was very evolved. The 1960s were a time of such cooperation between the sexes, a kind of unification. That’s one of the reasons it was such an amazing time: people were looking for answers outside of themselves. I think he says some really beautiful things on the nature of love and equality in the film.

Did you become a fan of his over time?

I liked his first album a lot, as well as some of his later stuff. Death of a Ladies Man not so much. I think his work is always very interesting and I think I was very influenced by it. Mainly I think because I was infatuated by Marianne and she was still clearly in love with Leonard, so of course, I listened to his stuff with great reverence.

The film touches upon his spirituality. Do you credit such calmness to this?

I think it must be. You never see him freaking out, he’s always very considered. I think he rarely had outbursts or lost it. He welcomed this approach of anybody could knock on his door at any point during a tour if people were having problems or just wanted to hang out. His room was always accessible, so he created this incredible family feeling – it’s hard to imagine many other artists doing that. He was very gracious in his treatment of people as a whole. He was a remarkable person.

Marianne and Leonard: Words of Love is released in the UK on July 26.

Follow Daniel Dylan Wray on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.