White Riot: how rock took on racism in Britain

- Text by Katie Goh

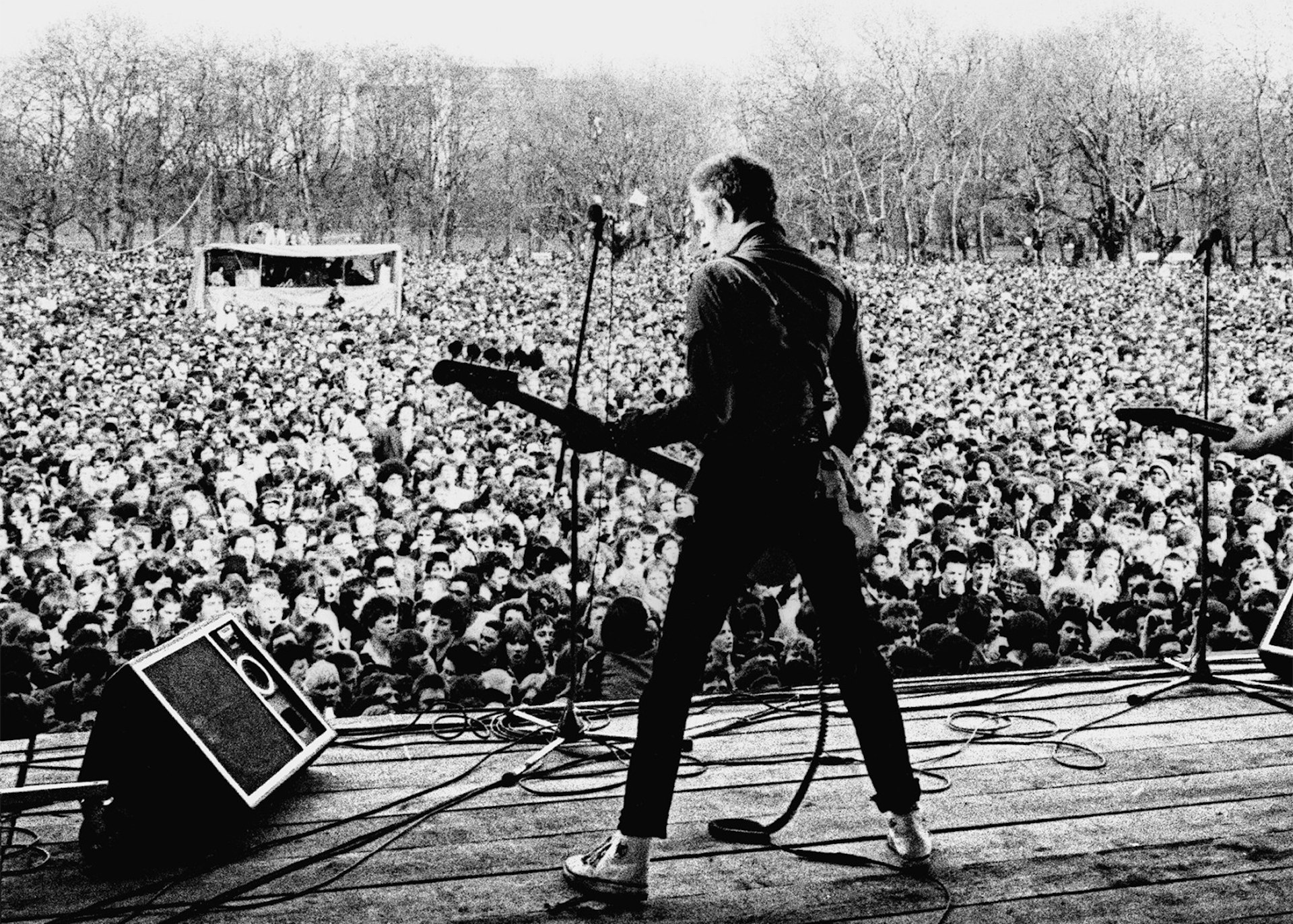

- Photography by Syd Shelton (main image)

It started in 1976 when Eric Clapton made a bold, drunken declaration of support for Conservative MP Enoch Powell’s infamous, anti-immigration “Rivers of Blood” speech. “Get the foreigners out,” Clapton shouted on stage before chanting the National Front slogan, “Keep Britain White.” For a small group of socially conscious music lovers, Clapton’s outburst was the final straw in the rise of far-right and racist rhetoric that was happening in the music industry – as well as Britain. The group, which included photographer Red Saunders, founded ‘Rock Against Racism’, one of the largest anti-racism music movements ever to take place in Britain.

Forty years on, Rock Against Racism is now the subject of Rubika Shah’s documentary, White Riot, which looks back on the origins of the movement. The film looks at how the grassroots movement evolved into a music festival with headliners such as The Clash, Steel Pulse, Tom Robinson Band and X-Ray Spex.

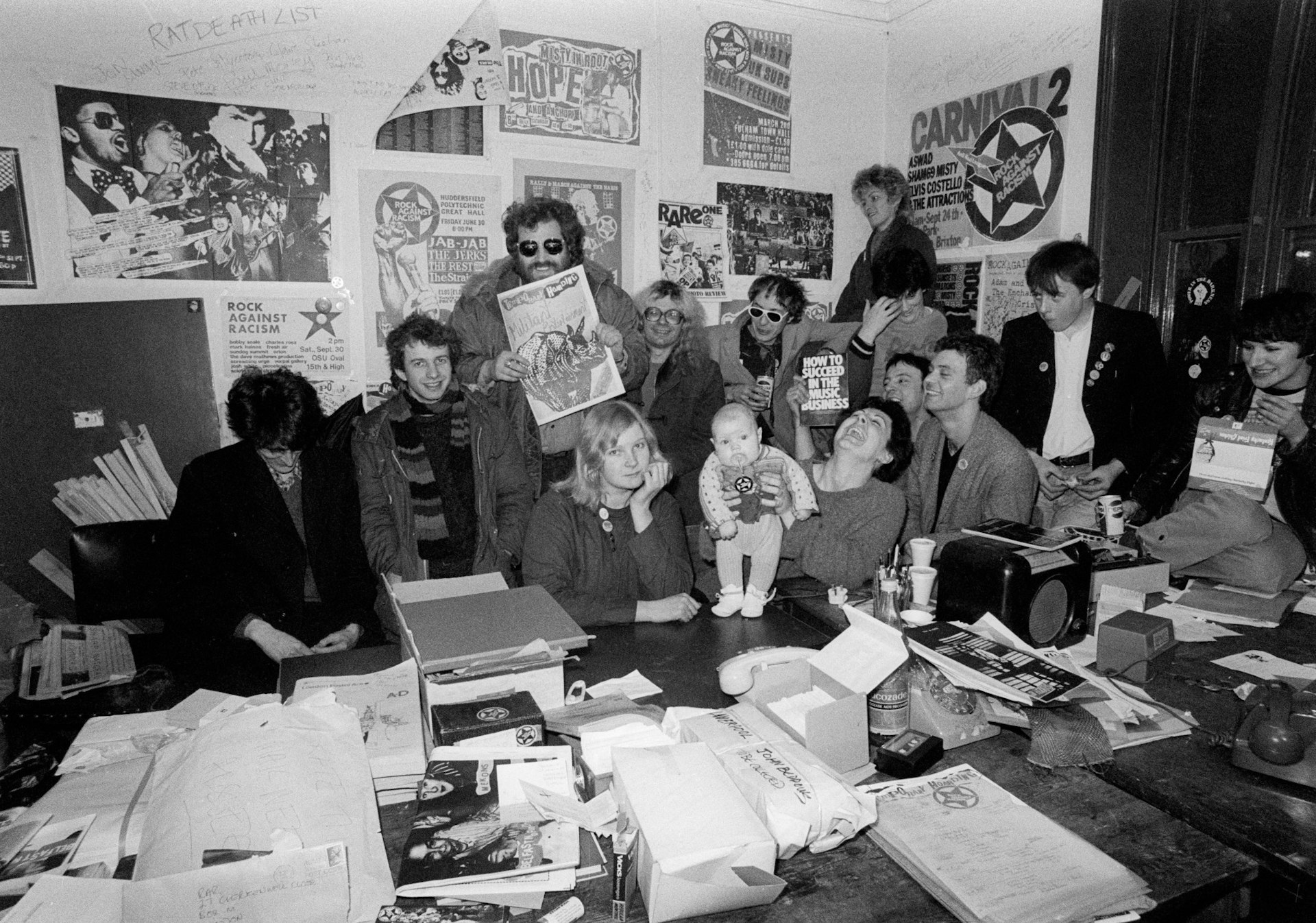

“It was a small group of everyday people who felt like they needed to do something urgently,” says Shah. Starting with a fanzine and small London gigs, Rock Against Racism quickly spread, springing up in cities across the UK from Belfast to Birmingham, before going international in Germany, South Africa and Australia. We spoke to Shah about telling the founders’ story, as well as the wider story of political activism in Britain’s music history.

What was your starting point for making White Riot?

I’ve always been interested in music stories with political change or social issues at the heart of them, and the idea that music gives people a voice. In 2015, I made a film about David Bowie and the Aboriginal girl in the ‘Let’s Dance’ video and I knew I wanted to find another story that was similar in terms of interest. I watched Chicago 10, a documentary about a group of activists in Chicago, and I was really inspired by it and interested to know if activists in the UK were doing something similar with music. We always look at America for those sorts of civil rights stories. But then I came across footage from the Rock Against Racism festival and I ended up finding my story.

Why do you think Rock Against Racism started in the ’70s? Why that moment?

Rock Against Racism started with a group of everyday people who got together because of a shared feeling of anger at the resentment towards minorities and rise in right-wing propaganda in Britain. They decided that they wanted to put on gigs with Black and white artists together on stage in unison and on equal billing as a show of solidarity. It started as a small idea, and became something much bigger, going on for five years.

They had a shared enemy because the National Front was growing more and more popular, getting time on national television and being legitimised. The National Front had really shocking, openly racist policies and there was a sense that urgent action needed to happen then and there. Rock Against Racism was just one of many grassroots movements created in reaction to the politics happening to fight that ideology.

The film weaves together personal stories from the movement with the wider political context, as well as music history. Was that a challenge?

It was a difficult process to make a film about a movement and distill it into 90 minutes. The things that were important to us were the fanzine, and the idea that it started with a small group of people and became a massive movement that included hundreds of thousands of people across the country. We liked that arc, so took those bits and started threading them together in the edit while constantly refining.

Image credit Syd Shelton

White Riot is about how music and politics are interwoven and how music has the power to change minds and ideologies. Do you think music still holds that power today?

I think so, but the problem now is people’s attention and where we get information from. Rock Against Racism was a grassroots movement that came from the people and I think that’s the crucial thing. And we are seeing that kind of grassroots movement today with Extinction Rebellion and Black Lives Matter. But whether the arts is doing the best it can, or being used the best way it can, is something else.

A lot of these things also get shut down and mainstream media doesn’t always agree with the arts, so how do you break through that or how do you get your message out to the people? It has to be grassroots. And that’s why Extinction Rebellion has done so well because they’ve reached people without mainstream media which Rock Against Racism was also able to do, albeit in a different way, and without Twitter or Facebook.

Has making the film changed your thoughts on the power of art as political?

It’s a grey thing. There’s the arty and creative side of filmmaking which I’m really passionate about, but then there’s also the business side of it, which involves getting the work out there and seen. I guess one can’t exist without the other in today’s world, but the machine of it all does get really tiring.

What surprised you when making White Riot?

It’s hard to say just one thing, because I look back on making the film and it was such a big part of my life. But I discovered something about people in making it. The people in Rock Against Racism did this amazing thing 40-years-ago, but they went on and did lots of other great things in their lives which they’re continuing to do, through activism, photography and lots of different ways. Like with Red Saunders, he wasn’t just an activist but also a photographer and actor, involved in lots of movements at that time. People aren’t just one thing and that’s inspiring.

Photograph Ray Stevenson

Interview has been edited for length and clarity.

White Riot is now screening in select cinemas.

Follow Katie Goh on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.