Countercultural history, through the lens of a fan

- Text by Andrea Kurland

- Photography by Glen E. Friedman / Ed Andrews

Glen E. Friedman is not a documentarian. So calling him one, in polite deference, doesn’t make for a great start. He doesn’t like open-ended questions (“I think you have to put it in more specific terms. What you are saying is kind of general”) or when you misinterpret what he says (“It’s idealise, not idolise. Not make them an idol, but an ideal.”) Invite him to dinner at your wife’s new restaurant and he’ll drop you like a bomb.

“Do you serve dead animals?”

“Um, yeah…?”

“Then absolutely not, no way.”

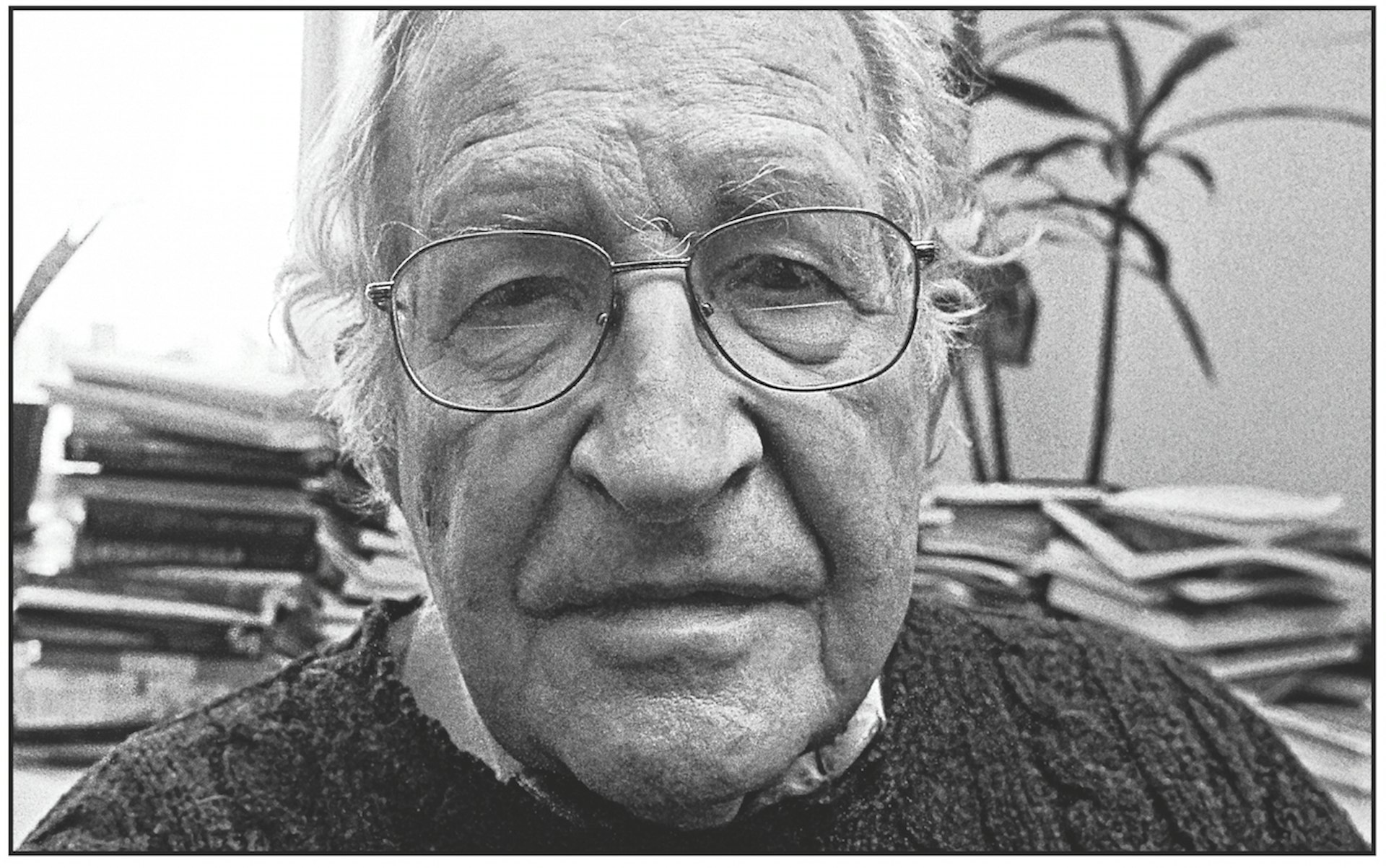

We’re standing in the perfectly lit atrium of the maze-like building that Glen has taken over in London’s Covent Garden. The walls are neatly lined with images from his new book My Rules, which collates peak moments of countercultural history as seen through the lens of a fan. Radical thinker Noam Chomsky gazes out next to a lanky Tony Hawk; Public Enemy next to Pussy Riot. It takes about ten minutes to get the lighting just right – Glen fiddles with the dials and squints into the shadows until the ambience feels pretty much identical to when we first walked in. Now we’ve stopped to take a break so that Glen can talk to a fan who wants to buy a print and, you know, casually invite him out for a bite to eat.

The invitation does not go down as planned.

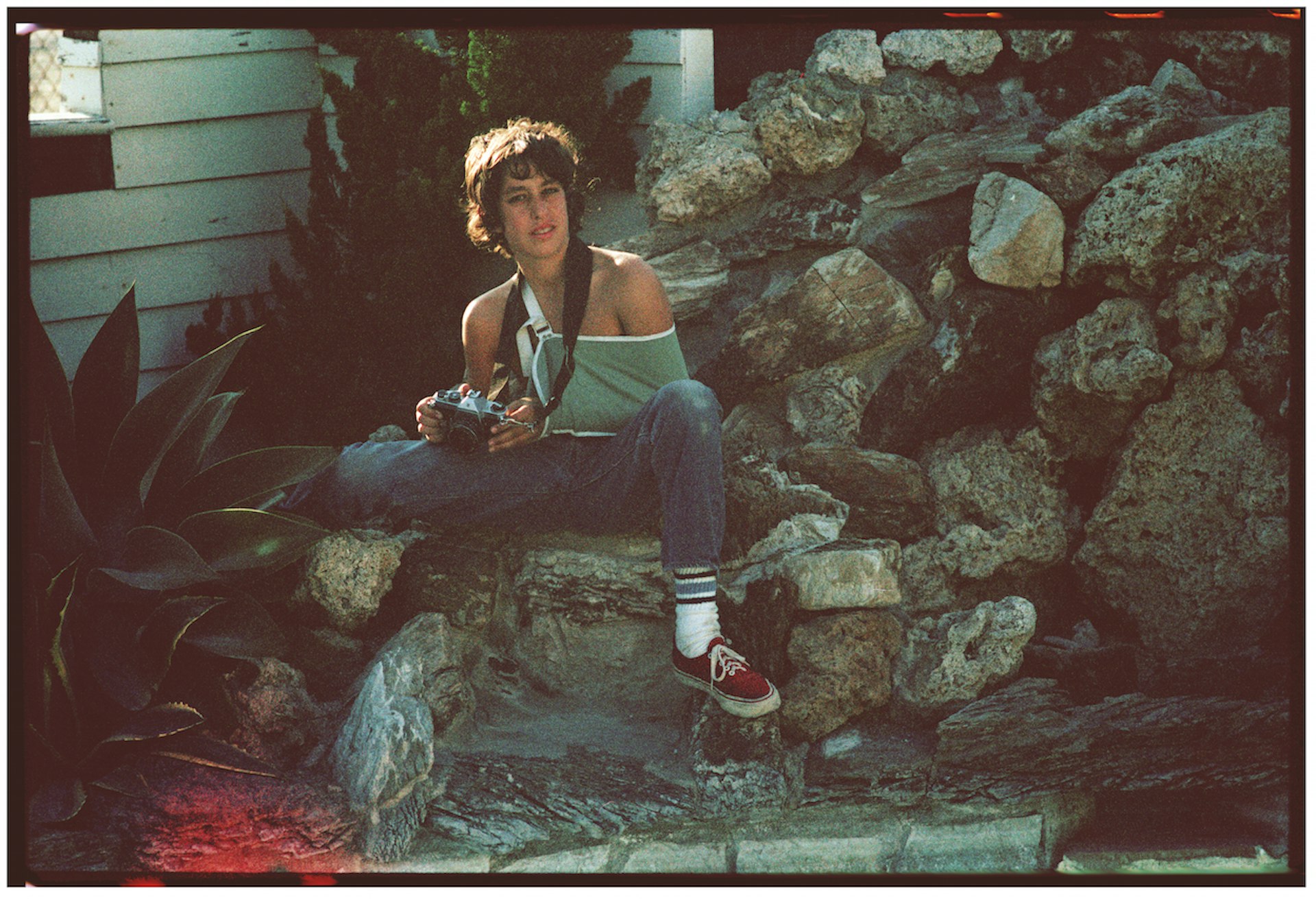

Glen E. Friedman by Hugh Holland, Santa Monica, 1976.

Glen E. Friedman is kind of curmudgeonly. But in the best possible way. While everyone else is pussyfooting around and playing the PR game, he knows what he likes, he knows what he doesn’t, and he’ll happily talk you through the difference. He’s Larry David in black denim and pins – exactly how a Straight Edge kid should grow up to be.

But in the mid 1970s, he was just a gangly pre-teen hanging out at drained pools with his friends. “I started taking pictures of skateboarders when I was twelve, but I would not call it ‘documenting’,” says Glen, who grew up between Los Angeles and New York and absorbed the best of both cultures. “Maybe it’s because I had friends on both coasts who weren’t seeing everything I was witnessing, but I knew there were people out there like myself who needed this extra energy, needed to know something else incredible was going on.”

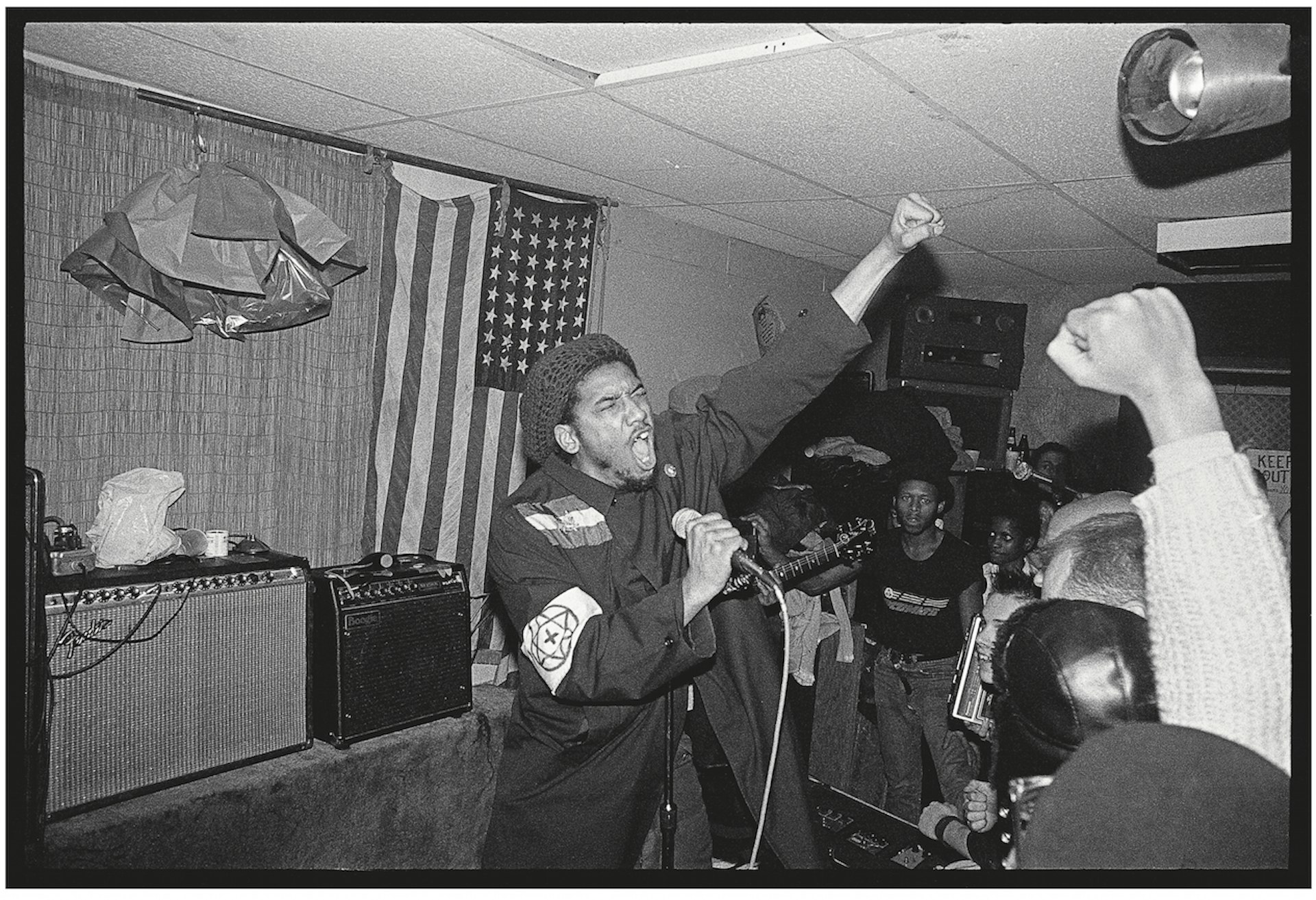

The images on these walls are a sweeping snapshot of what Glen witnessed in a succession of explosive big bangs. He was there when Southern California’s drained ditches and bone-dry pools became a hotbed of self-discovery; the first image he ever had published is from the same roll as that fabled soaring black-and-white Jay Adams shot, from October 1976, that’s as iconised as Dogtown itself. He was there when Black Flag, the Dead Kennedy’s and Bad Brains lost their minds and set fire to an entire generation. And he was there when Ian Mackaye, still a friend for life, channelled those flames – via Minor Threat, Dischord Records and Fugazi – into an urgent manifesto that gave kids an immortal sense of agency. And he didn’t stop shooting when he was sucked into hip hop’s orb by that same radical call to action. As Shepherd Fairey puts it in the intro to My Rules: “I remember seeing Glen’s cover for Public Enemy’s Yo! Bum Rush the Show and thinking, ‘This looks dangerous, like an insurgency being planned… and I want in.’”

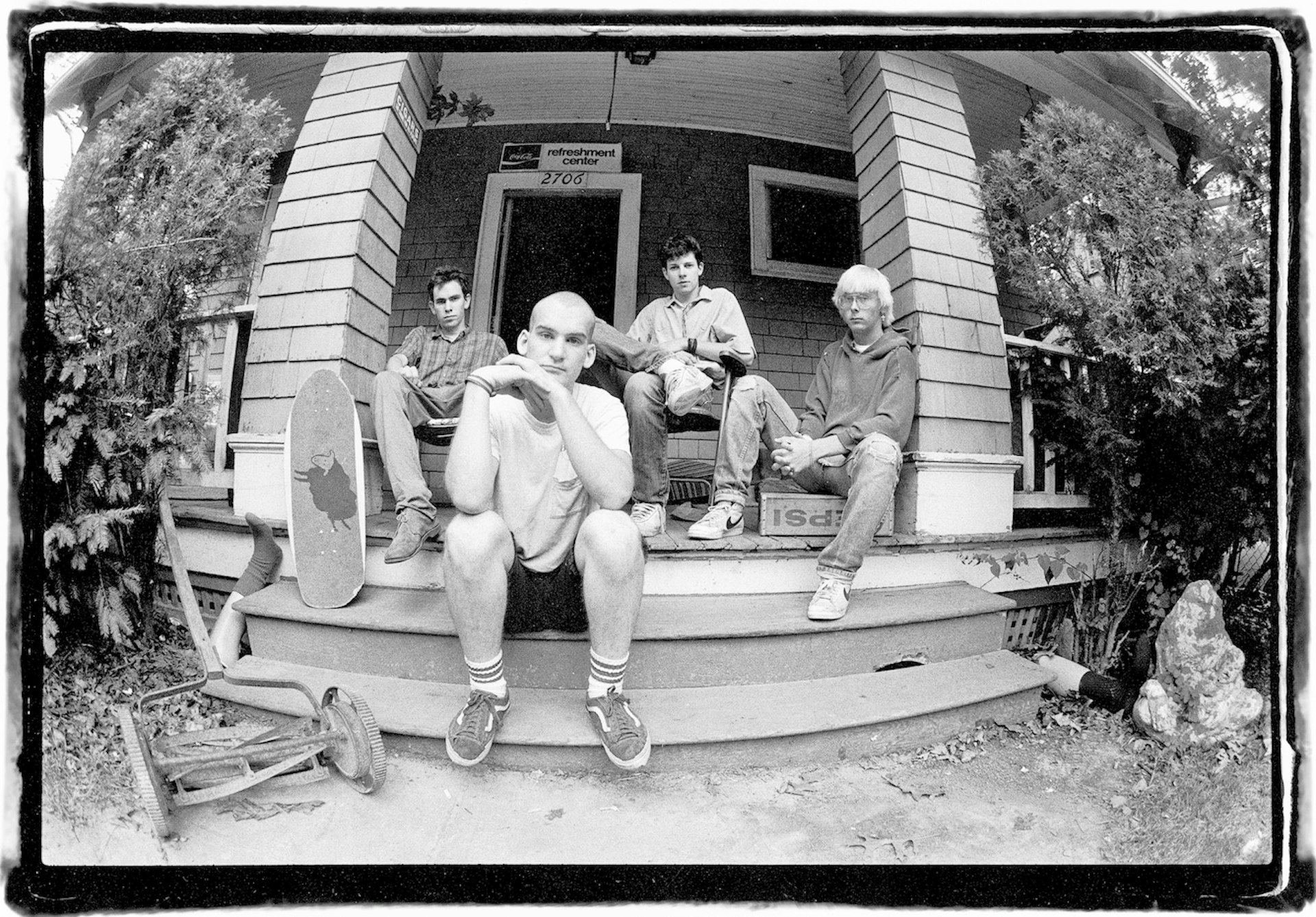

Dischord House.

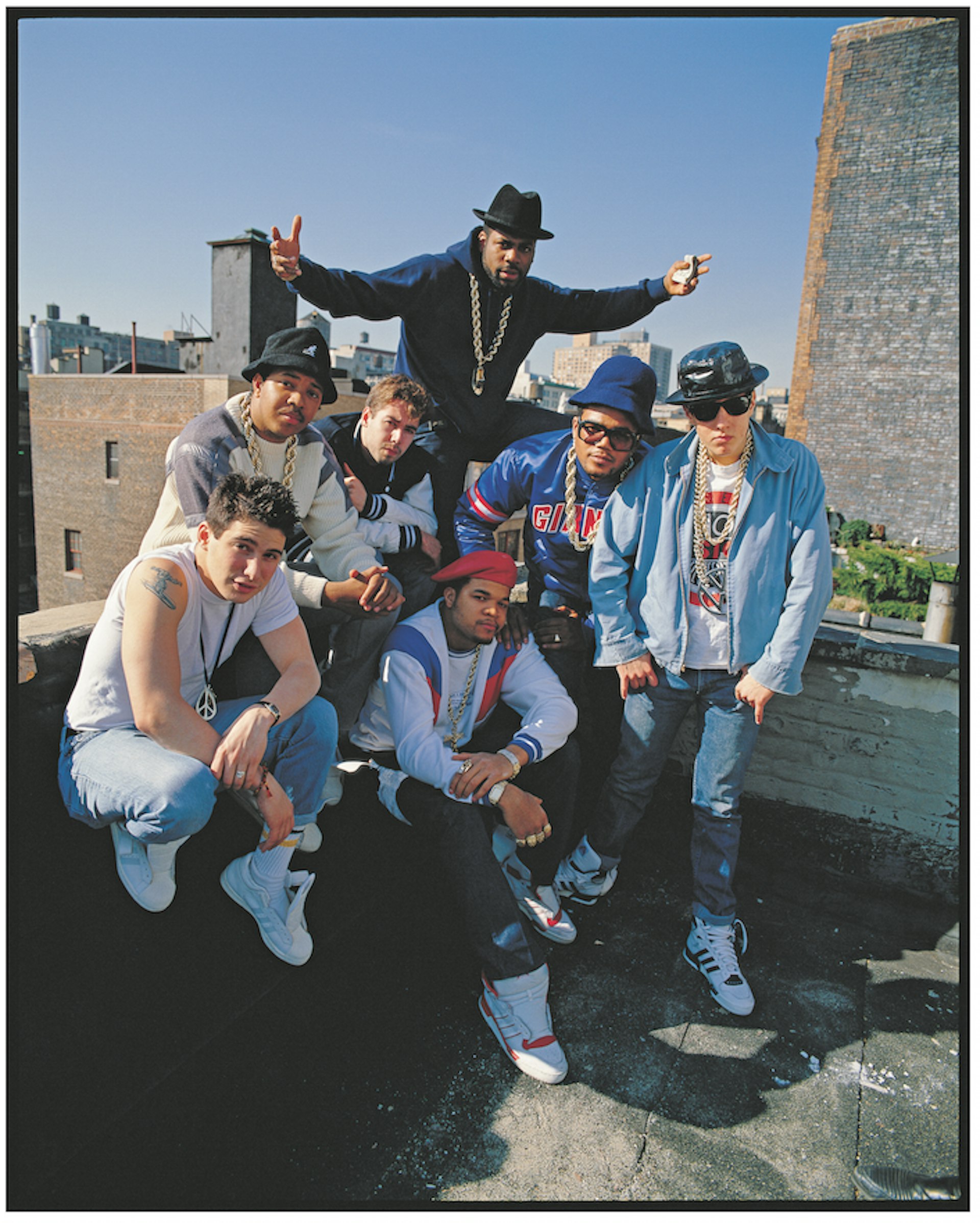

Run-DMC and Beastie Boys, NYC, 1988.

Glen takes us to the next room and heads straight for the lights. He tinkers at the levels in silence. A shot of Minor Threat on the steps of Dischord House – the DC label’s storied base since 1981 – comes sharply into focus. The Beastie Boys step forward with the same attitude, circa 1991. “Adam Yauch was like, ‘I want a picture of the Beastie Boys that’s as good as that shot [of Dischord House].” explains Glen.

The images that surround us are caught in a feedback loop that sees them romanticised and re-appropriated by every generation – idealised (not idolised) by every kid who steps forward to make something happen on their own. “To this day, thirty years later, there’ll be a kid sitting on my porch having their picture taken,” says Ian Mackaye, who still spends “most afternoons” at Dischord House even though most of the label work has moved to another location.

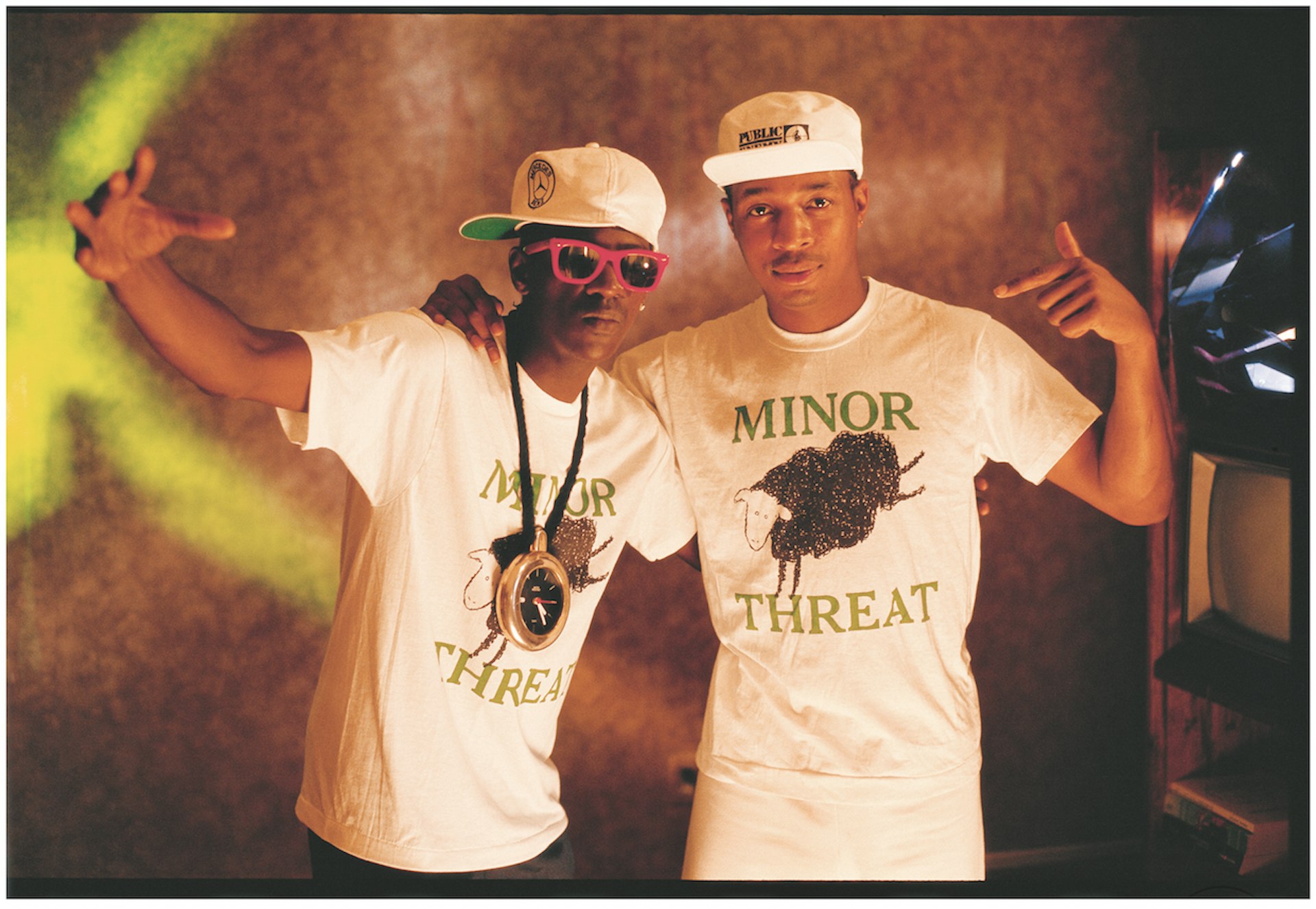

And that’s where Glen E. Friedman is probably right. He’s a conduit, not a documentarian. “I made them look good to help spread their seed,” he says. As the centre-point to at least three fully formed worlds – skateboarding, punk and hip hop – he became a kind of cross-pollinating force by focusing in on the attitude that bound them. Look again at that shot of Public Enemy from 1987; they’re wearing Minor Threat Out of Step tees. Look beyond Rodney Mullen pirouetting in a playground, circa 1982, and Minor Threat are hanging out in the background. It’s Glen who cut and pasted these scenes (he invited Ian to hang with Mullen, and gave Chuck D that black sheep tee) even when the rest of the world insisted on divisions.

Rodney Mullen and Minor Threat.

Flavor and Chuck D, Public Enemy, circa 1988.

“I had such a difficult time getting the first book published,” says Glen of Fuck You Heroes, which he eventually self-published in 1994 and distributed via Henry Rollins’ 2.13.61 Publications. “People didn’t get it. ‘Musicians and skateboarders in the same book – what’s the connection? How are you going to put mostly white punk rock people with mostly black hip-hop people – who is this speaking to? You have got to separate them.’ I was like, ‘It’s all about the fucking attitude! It’s about the attitude and the drive – and the heart! Something you all in these big fucking publishing houses don’t know anything about.’”

Glen immersed himself in the movements that sucked him in to the point where he became a part of the flow. In the mid 1980s, he helped Run-DMC street promote their early shows, shooting singles covers and a tour book, and went on to work with Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin at Def Jam Recordings. According to C.R. Stecyck II, Glen’s video work for Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions To Hold Us Back (1988) “helped create a visual standard for politically concerned individuals to identify with”.

It’s an uncanny thing to think that one fiery little kid can be in the right place at so many right times. But maybe that’s what happens when you know exactly what you like, and you’re not afraid to get in on the action.

“Truth and beauty reside wherever one is lucky enough to find them,” writes Stecyck, kind of epically in My Rules, from his vantage point as skateboarding’s original historian. “Glen E. Friedman works overtime attempting to ferret them out and present their essential characteristics in a manner that others can learn from. This man’s mission is to distil it all down and to then serve it straight up and right at you.”

So here’s Glen, soliloquising and looking back, taking a break now and then to dig into a bowl of vegan food from “this great little Egyptian spot around the corner.”

Be A Fan

“I was inspired by these people, and that’s why I started taking pictures. I felt a sense of responsibility, like, ‘People do not realise how important this is, so I’ve got to do justice to the subject.’ I could see the point where it would no longer be just us. It was exciting to me, so I thought it should be exciting to other people; it should wake other people up the way it woke me up. It kicked me in the ass and I wanted it to kick other people in the ass.”

It’s ‘Idealise’ Not ‘Idolise’

“Here I am fifteen years old taking pictures of my friends skating. I am a skater and I know what that big moment is, or what looks like the big moment. I want to portray it in a way that is incredible. Catching that intense perfect moment as close to the action as possible. I make the skaters look better than they are. That is my job. You want better things for your children then you had. I mean, they look good, but they did not look that good! It may be just 1/60 of a second in that person’s history, but because it’s seen over and over, it becomes ingrained that that is that person – even if it is not – and that makes me more responsible. I am not fucking around.”

Allen “Ollie” Gelfand, Hollywood Florida, 1979.

Reminisce Don’t Romanticise

“I never say those were ‘the good old days’, because there was plenty of depression and negativity that went on all the time, but there are some fun stories to tell. Like, ‘I’m getting chased from a pool by a guy with a shotgun, or jumping down a hill through some ivy and my camera case is gone and I don’t know where it is and someone has got a chainsaw going.’ It sounds like a movie… But not every record back then was good. There were a lot of shitty punk bands, a lot of shitty hip hop groups, and a lot of skaters that were whack.”

Show Some (Mutual) Respect

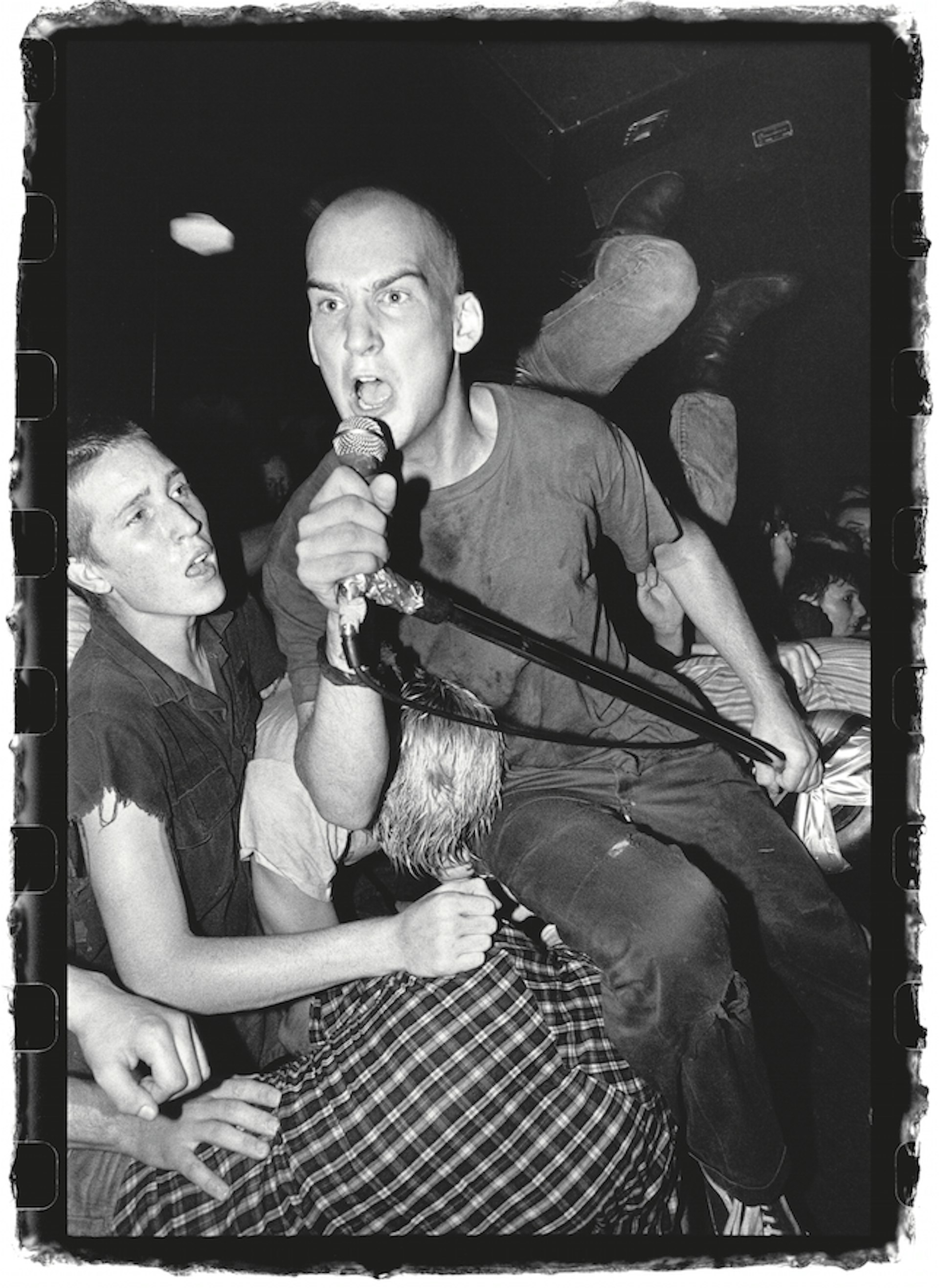

“I met Ian Mackaye at a Bad Brains show. And I met his brother [Alec, who fronted The Faith] the same night; The Faith was opening up for Bad Brains. Ian fondly remembers the date [December 26, 1981, at CBGBs]. Ian and his brother and Henry [Rollins] all knew me from //Skateboarder Magazine// years before I knew them. When we met I did not really know Minor Threat. Then I got my hands on In My Eyes and all of a sudden my level of respect for him just went like, ‘Wow, this record is fucking amazing!’ It was the best thing I’d heard since the latest Black Flag record. And they were fucking phenomenal live. You wanted to share that intense energy. That one-to-one thing that he gave on stage – very few singers did that. He never spoke down to the audience.”

Ian Mackaye of Minor Threat, Washington DC, 1982.

Wake Up

“I was politicised at a young age. I was always very aware of who was running for president and what was going on with the Vietnam War. But as a pre-teen – before punk rock – when we got into skateboarding we became more self-centred, even though what we were doing was political in a way. The incredible thing about punk was that, all of a sudden, everything was controlled by us. Even if it was more of a personal politics rather than a governmental one, it was inspiring as a young person to think, ‘Hey maybe we can affect some kind of change.’ It was our creativity, our own imagination that made these things happen, in pools and at gigs. There were no adults to guide us. A lot of people think DIY is a decision. It was not a decision – it was the only way.”

Do It FOR Yourself

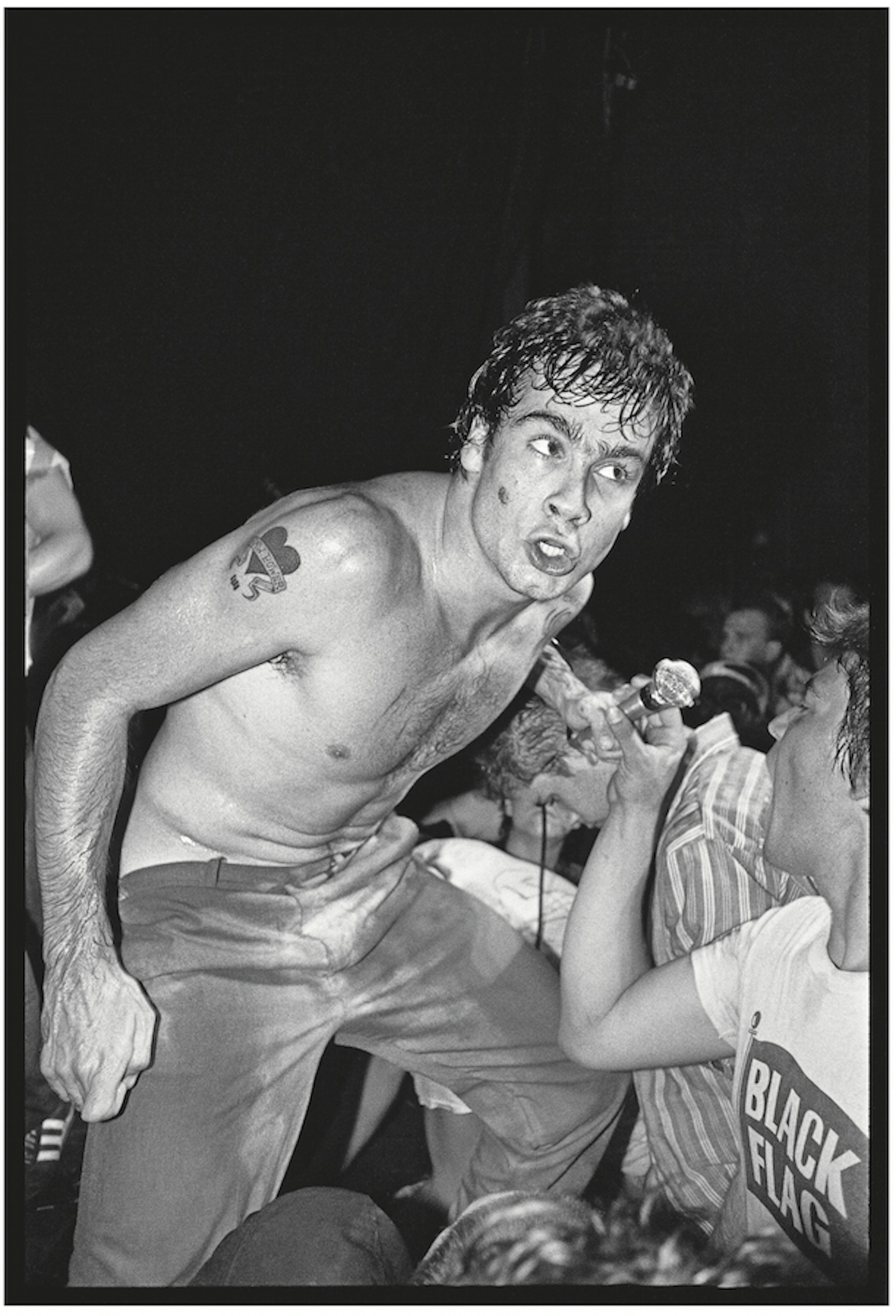

“Black Flag practised harder than they played live. You have never seen somebody exert as much energy anywhere in your life. I cannot say that every single person on these walls worked that hard, but most of them did. It does not just happen overnight for anybody and it certainly did not back then. It was much harder to get attention. Sharing what you do with other people was not something people did. The cream rose to the top; maybe if you were fantastic or had the right connections, you would be in a magazine. So most often that was not even a goal. What was important was that you got to create and do something on your own, to maybe entertain your friends, or to push the limits of what you know in a way that satisfied you personally. Most people did not know or give a shit about what you were doing. Everyone did their own thing.”

Henry Rollins of Black Flag, 1982.

Undertake That Pilgrimage

“I went to DC to see Minor Threat play one summer, when I was visiting my dad in New York. They let us into [Dischord House] like they let most people into their home, which is how it was back then. It was a communal-type house, all these kids living amongst themselves, cooking and eating and just hanging out; they ran [Dischord Records] out of there and everything. I didm’t know that many kids who had houses. It was enlightening to be around such nice, cool people. Some years later, Ian turned me onto the whole vegan thing. I mean, I had heard about vegetarianism from Shawn Stern [founder of BYO Records]. He had given me pamphlets that really changed my ideas about food and the planet. I was on my way, but then I spent that week down in DC with Ian eating all vegan and saw that it was not that hard. Because, trust me, in 1987 people looked at you as a Martian. After that trip I stopped eating animals altogether.”

Just Say (Fuck) No

“I never drank. Ever. Drinking is a learned behaviour as far as I am concerned – an acquired taste which is really stupid and pathetic. No one likes the taste the first time they do it. You just do it because you want to be accepted by some bullshit peer group. Quite frankly drinking, smoking, doing drugs, is about as conformist as you can get. It dulls your mind. The corporation is controlling who you buy this shit from… Hearing about the whole Straight Edge thing that Ian was involved in, that was something I could relate to. Most kids do not realise that there are other people out there that think like them. When you hear another person talking about it, it helps you in your journey through life to have more confidence in what you want to do. Ian and his lyrics did that for a lot of young people.”

Pussy Riot, 2013.

Keep Movin’ On

“When people ask me, ‘What’s the next ‘thing’?’, I’m like, ‘I am fifty-two years old. Ask a twenty-year-old, not me.”… I was inspired as a fifty-year-old by the Occupy movement and I participated in that. I am inspired by the Anonymous movement, but I am more of an observer… This is a special time, too, but not necessarily for youth culture. Maybe for the whole fucking planet it is time to wake up because the planet is going to spit us out and we will all be dead because we are going to destroy it. Our environment, that is. The planet will always be here. Eons longer. Until it explodes, right? But humans will not be here on the planet.”

Know Your Noams

“Why did I shoot Pussy Riot and Noam Chomsky? Why did I shoot two bad-ass women and a fucking incredibly inspiring genius of our time who knows everything – who talks politics in a way like no one else is honest enough to do? Pussy Riot, the way they stood up against their government and fought for what they believe in, speaking out against what they think is bad, I mean, who the fuck do we know that ever went to the gulag?”

Noam Chomsky, 2013.

Respect Rebellion

“Rebellion will always be relevant until we are living in a perfect world, right? Somebody has always got to be fighting back to make things better than what they are. That is really important, not to just lay back and sit back and let things happen around you but really to be a part of what is going on and motivate people to think in ways that will make the world a better place. It sounds a little lofty and idealistic, but really that is what this is all about. Can we take a food break now?”

Tweet Less, Think More

“I hope there will be something [as rebellions as punk] for my son, but I can’t imagine what… Something about the nature of communication these days, and media – it limits youth in some ways, and propels them in others. Instant communication makes people lazy. It’s great they can all talk. But people are not developing, are not nurturing their own thoughts too long because they just share them with their friends on Facebook or on Instagram immediately. It’s good to think in the moment. But for things to be truly great, you have to take a lot of time in mastering what you are doing. Alan Gelfand did not learn to ollie just by accident. Ian Mackaye did not make good music by accident, nor did the Bad Brains or Black Flag. These fuckers worked their asses off.”

H.R. of Bad Brains, NYC, 1982.

Track Back A Little, Every Now And Then

“When I see young kids at my shows, I am happy there is respect and appreciation of the culture. And I also give them credit for actually coming to see it. Because most kids don’t come into a gallery space and they don’t care. Those kids are obviously going to be the trendsetters or the leaders of the community because they are coming to find out about something that other kids are not taking their time to understand. People who take their time to look back at their roots and see what else has been going on on the planet – other than video games, right? An appreciation of your roots is not so important. But it certainly helps things move along, so you won’t make the same mistakes other people made. Everyone knows you can learn from the past… I am almost done. I am a slow eater. I hope my last bite does not have cardamom in it.”

My Rules is published by Rizzoli.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.