Growing up behind the counter of a Chinese takeaway in Wales

- Text by Ian Wang

- Photography by Hui with her parents in 2018 (main image). Images courtesy Angela Hui

In the past several years, the Chinese takeaway – once a staple of Britain’s towns and villages – has been in decline. Threatened by a combination of rising prices, competition from food ordering apps and a new wave of racist stigma, many Chinese takeaways have been forced to close. What’s being eroded is a long chapter of working-class immigrant history, with takeaways being one of the main ways poor or uneducated Chinese migrants could make a living in post-war Britain.

Food journalist Angela Hui understands what’s being lost better than most. In her new memoir, Takeaway: Stories from a childhood behind the counter, she documents her own family’s takeaway in South Wales over its 30-year-life, from its opening in 1988 to its eventual closure in 2018. The intervening years are filled with stories of hustling in the kitchen to meet the evening dinner rush, or venturing to Cardiff to stock up on ingredients, along with the alienation of being one of the few Chinese families in her village and dealing with a constant stream of racist harassment and vandalism.

Hui’s book is mostly a reflection on the past, but it’s hard to ignore its contemporary political resonance. As she writes in the author’s note, “the East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) community in the UK and across the world has been uniquely scrutinised” in recent years, from Covid-19 racism to the Hostile Environment. Takeaway offers a snapshot of what that scrutiny feels like, and how we might begin to resist it.

Huck spoke to Hui about rural immigrant life, the takeaway as a community space and how to keep ESEA activism alive.

What impact do you think the closure of Chinese takeaways is having on British Chinese communities?

Many British Chinese families who run takeaways up and down the country are at a fork in the road. To sell or not to sell? Will the next generation carry it on? And will they or will they want them to? It’s a hard, life-changing decision that’s tinged with nostalgia, sadness and pride.

For most families, Chinese takeaways are their livelihoods and this is all they know. Now, with inflation, staffing issues and more competition, working in hospitality is harder than ever. For my parents, they felt directionless in life. What next? What do we do? What are we without the takeaway? Many Chinese families are having to reassess and figure out their footing in the world having lost something that was so central in their lives.

I think when Chinese takeaways close we lose a part of history. All these Chinese takeaways that were positioned in rural outposts, seaside towns or on the high street in remote villages, they all serve a purpose and they serve their communities and many relied on them for their daily or weekly chat and for food. Without them, villages and towns will be a little less delicious and colourful.

You mention in the book how many ESEA groups are often widely dispersed throughout the UK. Why do you think there is less focus on rural areas and issues of social isolation when we talk about immigrant life in the UK?

When we talk about anything from life in the UK to culture and food, everything is so London-centric and it’s impossible not to get swallowed by the London bubble. There’s a misconception that nothing really happens in rural areas, but break free from the capital city and you’ll find diverse stories, larger-than-life characters and culture that I personally find way more interesting. I recommend Vittles’s rotating column on Red Wall Feasts (for subscribers only, but sign up) that focuses on food culture in the north of England, Road to Nowhere, Mother Tongue, Fat Boy Zine, Filler Zine, Rhondda in Colour, Bleak Fabulous and more.

Hui’s mother cleaning at the Lucky Star

Despite not growing up around many Chinese people, in the book, you discuss places like Chinese school where you had the feeling of being a cultural majority for the first time. What role do these community spaces play in forming young ESEA people’s identities?

Such a huge part! I didn’t realise the importance at the time and fought my parents every step of the way. My parents made a huge effort for us to be in these cultural sites, to be surrounded by friends and cousins, to eat Chinese food and to learn our language, because that’s part of who we are. I’m so grateful and lucky to have spaces like these available to me, as I know many other young ESEA people don’t have that and it can be an extremely isolating experience.

You describe your parents as having, like many immigrants, an ambivalent relationship with the police. One issue ESEA activists have been debating is how to combat racist violence without relying on the police, who are often racist themselves. What can we do to better protect community spaces like takeaways?

Please read our stories, listen to our genuine concerns, understand our experiences and act in solidarity. Don’t leave it up to BIPOC to do all the legwork. It takes more than sharing an infographic or reposting a traumatic news story about a racially-charged attack, then asking POC ‘Have you seen this?’ or ‘Why aren’t you talking about this?’ Chances are they’ve seen it, might not want to feel pressured to talk, and are traumatised. Learn and train in bystander intervention to step in, to help and stand up for community spaces, and use your voice when others can’t.

One criticism raised by some ESEA activists is that there is too much focus on representation in elite spaces like Hollywood or politics rather than ordinary working-class migrants. How can we shift that focus?

Look a little deeper and turn to the good work that many excellent grassroots organisations are doing – the majority of them are from working-class backgrounds. They might not have the same global representation-pulling power as Hollywood, but charities, organisations and individuals that don’t get a lot of press or recognition are doing a lot of the important groundwork, making a change for the next generation and being unafraid to stand up for what’s right.

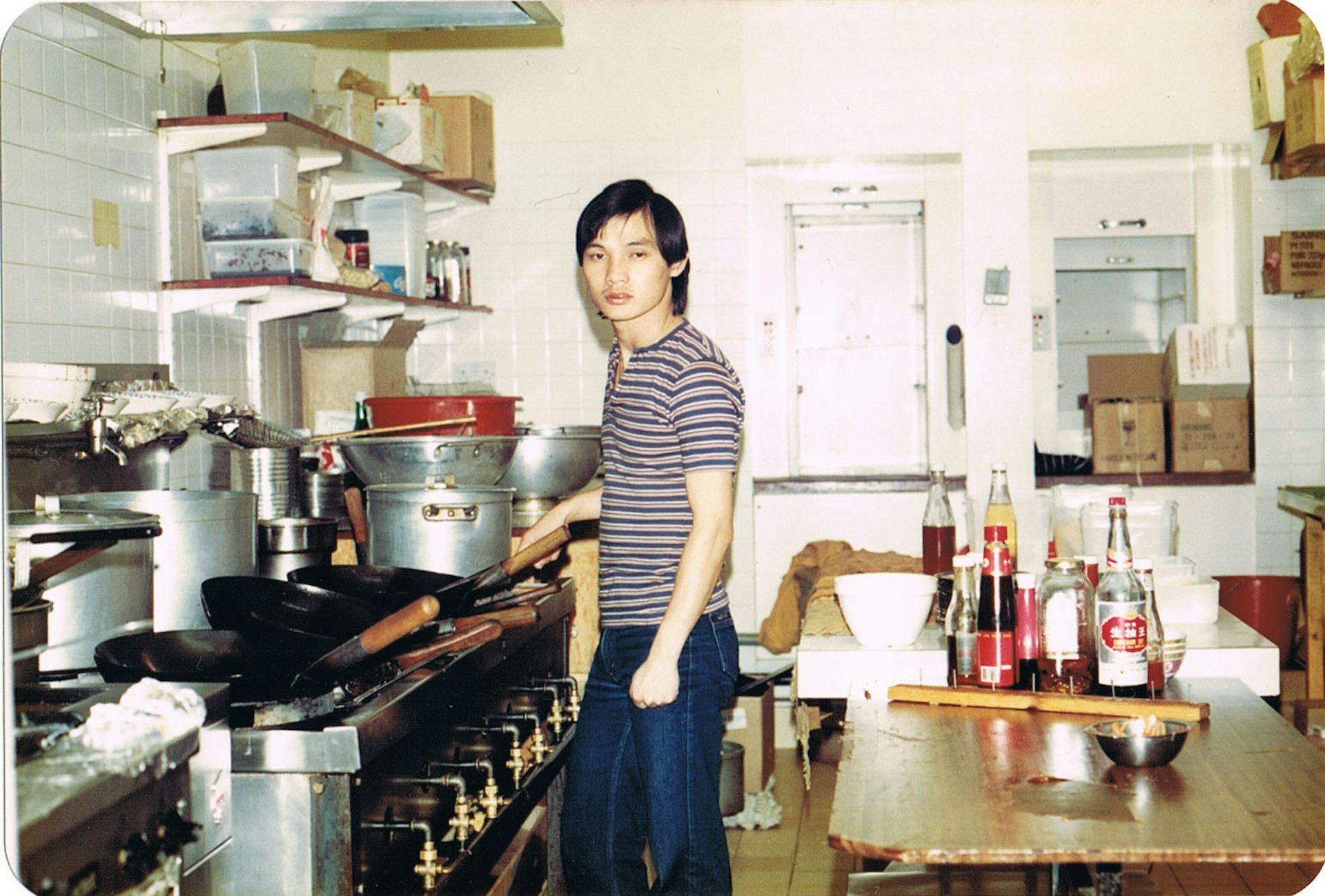

Hui’s father cooking at the Lucky Star in the ‘80s

Take Hackney Chinese Community Services and London Chinese Community Centre, for example. They’re charity organisations that rely on donations in order to offer a lot of services to the Chinese community, such as mahjong club, lunches, language courses, mental health resources for the elderly and more.

This is just a fraction of the good work that people are doing but other examples are Celestial Peach’s #ChineseFoodiesofIG100 online exhibition; Besea.n’s ESEA heritage month; the podcaster Chinese Chippy Girl, who campaigned to improve children’s publishing; creative platforms like Don’t Call Me Oriental and Baesianz; and ESEA sisters, a collective safe space for women, trans, non-binary and genderqueer folks of Eash and Southeast Asian descent.

You have a section towards the end of the book suggesting further reading by other writers in the ESEA diaspora. Why was it important for you to include this, and what do you hope the future holds for ESEA literary culture in Britain?

It felt right to acknowledge others and rightfully credit any research and inspiration I read during the book writing process. Maybe it’s just my ingrained filial piety playing up, but it’s important to respect others who have done the groundwork or come before you. I recently read an excellent piece by Anise to Zataar about the importance of ethical practices when it comes to recipe writing and I think it can be applied to writing in general.

I feel hopeful about the future for ESEA literary culture in the UK! There’s been a lot of new ESEA literature, which makes my heart swell. More stories and more people taking up space, please! It’s a slow process and playing catch up to its American counterparts, but more representation can only be a good thing.

A family meal before work begins

Takeaway: Stories from a childhood behind the counter is available now.

Follow Ian Wang on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.