Idyllic photos of Bristol’s allotments over lockdown

- Text by Huck

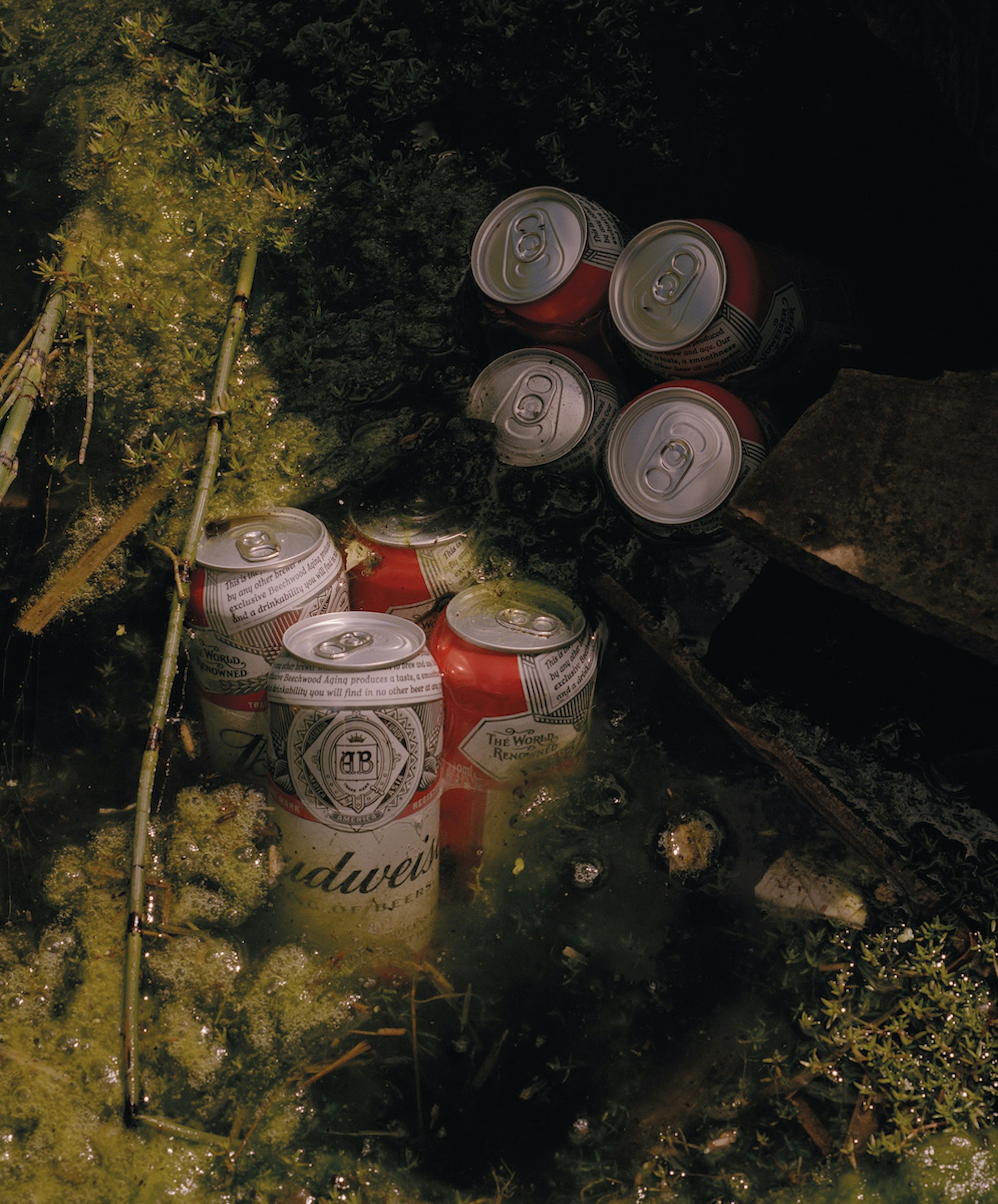

- Photography by Chris Hoare

Allotments – small parcels of land rented to individuals, usually to grow food and vegetables – have existed for hundreds of years in Britain. The system dates back as far as the 19th Century, when land was given to the labouring poor, allowing them to grow food at a time of rapid industrialisation with no welfare state in place.

During the Second World War, millions of people across Britain ‘dug for victory’, planting vegetables in their gardens to feed their families amid rationing and food shortages. At the time of dig for victory, 18 per cent of the UK’s fruit and vegetables were grown in gardens and allotments, but since then, the system’s popularity has wavered, falling to just three per cent in 2017 to 2018.

Last year, Bristol photographer Chris Hoare was commissioned to create a series by Bristol Photo Festival documenting the city’s allotments. These photos are now collected in a new book, titled Growing Spaces (RRB Photobooks). “I’m not a gardener, but I’ve always wanted to go into them,” he tells Huck. Over the past couple of years, allotments have seen a spike in popularity among growing numbers of economically and environmentally conscious young people, families and ethnic minorities claiming plots.

In Bristol, like many other cities in the UK, the waiting list for plots is significant – often over 18 months – and gaining access to these spaces is not all too common. “They’re quite private and exclusive in a way, unless you know someone who has one,” says Hoare. “You don’t really ever get to go into one because they’re always locked.”

While the idea for the project was conceived before the pandemic, Hoare ended up working on the project in lockdown, at a time when interest in allotments soared. For many, allotments offered a source of solace, sanctuary and community spirit over a time of crisis. And in lockdown, the importance of nature in maintaining good mental health became all the more apparent.

When Hoare was given the chance to go to an allotment, he says he was struck by just how much of an “oasis” it was. Beyond offering people a place to grow food, Hoare says he was surprised at just how social they are as spaces: “Sometimes people will go down to their allotment, and they won’t do any gardening stuff. They’re just hanging out with people. There are parties, barbecues and fires – they’re just amazing,” he says.

Through the project, Hoare says he wanted to counter the idea of the typical allotment goer as a “white, middle-class retiree”. In Bristol, he says, “There’s a big, elderly Caribbean population on a lot of the allotments, for example,” he says. “In general, it is a lot more complicated than the general stereotype.”

Hoare says that the older-allotment goers he spoke to say they’ve noticed an influx of younger people entering the spaces over more recent years, as well. “I think young people are more conscious of where they’re getting their fruit and veg from,” Hoare observes.

Hoare – who is currently on a waiting list for an allotment – is fairly certain the interest in allotments will carry on post lockdown. “The whole nation really threw itself into gardening last year,” he says, “and I hope it continues that way.”

Growing Spaces is available now on RRB Photobooks.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.