Documenting two centuries of British nightlife with Hacienda DJ Dave Haslam

- Text by Alex Taylor

- Photography by Various, see captions.

British nightlife’s been through a rough time in the last ten years. In London alone, The Astoria, Plastic People and the 12 Bar have all closed their doors for good. Even Fabric nearly lost its licence earlier this year. We’re now in state where 1,411 clubs have closed since YouTube was founded, although the two are totally unrelated.

At this point, you might be lighting your torches and readying your pitchforks for the inevitable rage bubbling deep inside to release itself on ‘The Man’ for attacking British nightlife. This isn’t any recent phenomenon, though. It isn’t even just something unique to this century.

In his new book, Life After Dark, Dave Haslam, a veteran of the Hacienda who played there over 450 times since his first show there in 1986, shows us that nightlife, evolution and clubbing culture have been surviving attacks on evening entertainment for as long as human beings have been looking for a way to get messed up. Going back to 1840, Haslam finds a quote from co-founder of Marxist theory and possessor of enigmatic facial hair Friedrich Engels on the streets of Manchester: “On Saturday evenings, especially, when wages are paid and work stops somewhat earlier than usual, when the whole working class pours from its own poor quarters into the main thoroughfares, intemperance may be seen in all its brutality.”

“Each generation thinks it invented staying out late and invented hedonism,” Haslam says. “But, actually, that is a very strong tradition in Britain, as the Engels quote suggested. And I like that, I like the idea that you can be walking through a town or a city, and you’re walking the same streets on a Saturday night as people have done for 200 years. I like the idea that there’s a unity and link between all of those generations.”

Our desire to get messy is something that links generations together, but what makes our generation different to ones before, could be our spending patterns. With student budgets being stretched further than ever before, rents increasingly unaffordable and pay stagnating, Haslam suggest that we may now be engaging with culture in a quick burst. It looks like we’re now saving up for long periods to go away to festivals instead of heading out every weekend. Obviously people still do that, but more and more of us are choosing to head to festivals in the summer to get the sun and tunes we can’t get at some sticky-floored, drippy-ceilinged, dingy ass club.

“I’ve been a DJ for 30 years now, and if you weren’t getting gigs in July and August, you weren’t working,” Haslam insists. “But now, there’s a great festival almost every week, and August is one of my busiest times of the year. So, I think people are consuming music differently. Maybe people are saving up for a concentrated dose of going out in Ibiza, or a concentrated dose of going to a festival, rather than going week in, week out to clubs.”

Last year alone, 10,000 people went to Hideout, Creamfields had a capacity of 60,000 each day, and 360,000 people headed to Belgium’s Tomorrowland festival. Going off these figures, it looks like there’s a serious demand for celebrating clubbing en masse. On top of that, a ticket to Creamfields this year would set you back £220 before booking fees. If you’re going to pay that much to go to a festival, chances are, you’re going to be into clubbing and so will the rest of the people there.

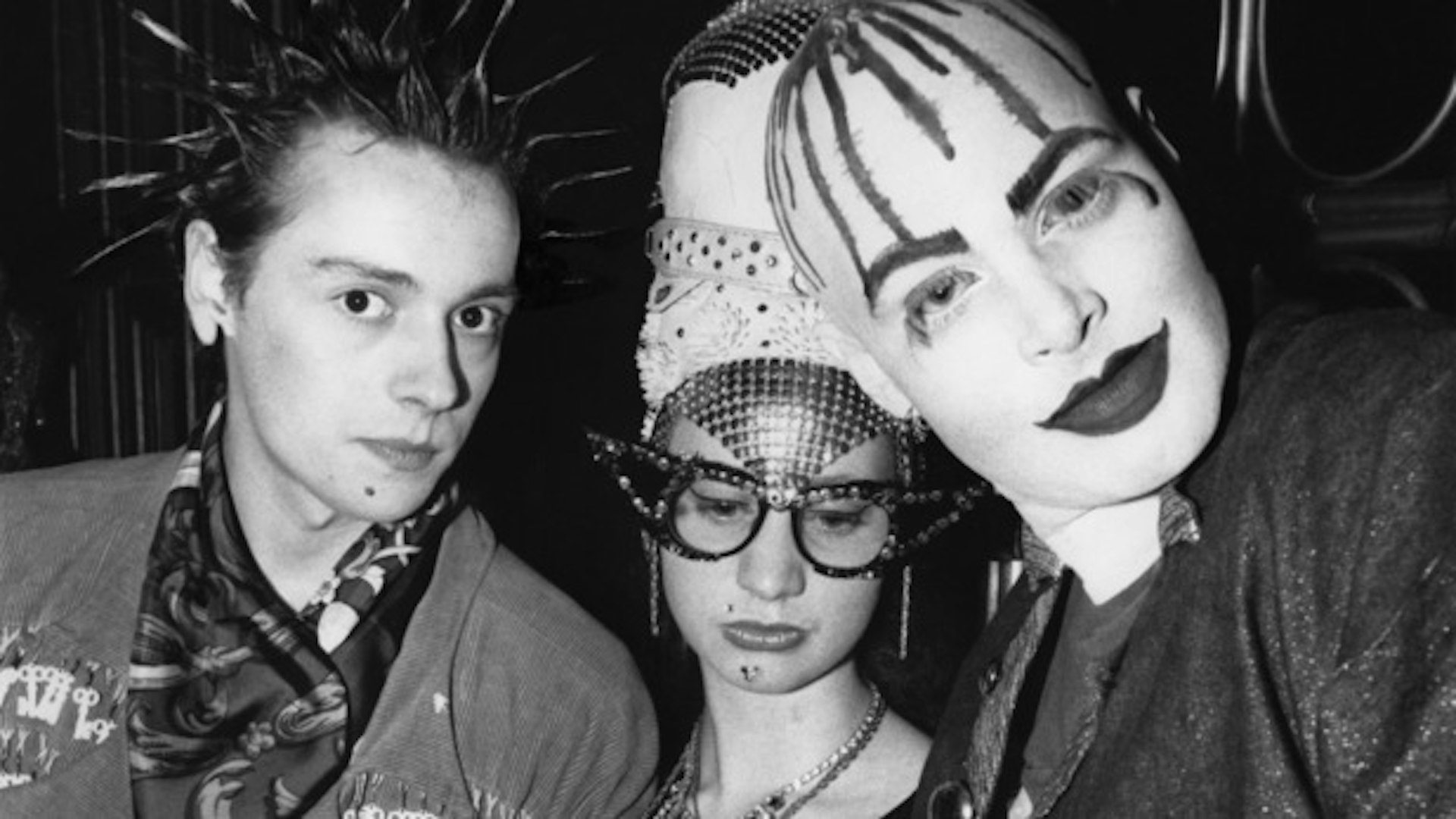

It isn’t a coincidence that people gravitate and move with like-minded individuals. The willingness to fork out for that much means you want to be part of that community, lose yourself in whatever you’re into, be that the music or something else. If there’s one word Haslam keeps returning to, it’s community. Our spending patterns may have changed, but wanting to be with people who think like us, look like us and act like us hasn’t. Whether it’s the scuttlers of 19th century Manchester fighting in the music halls, the Punks flocking to see the Sex Pistols’ residency at the 100 Club in the 70s or the Gay community in the backstreets of Soho, people’s taste in nightlife moves with others of a similar mindset.

To Haslam, the sense of belonging when you’re clubbing can’t be stressed enough. Words such as ‘community’, ‘home’, and ‘church’, are all familiar to people who’ve got past the bouncers and had the best night of their lives in their favourite clubs.

“I think a lot of people maybe struggle to find somewhere they belong,” he says. “I think a club is, historically, something that people have gravitated towards and this is particularly strong in the gay community and the black community where there have been quite a lot of negative social pressures. People in those communities have found nightlife venues to be a place of refuge and somewhere to celebrate their identities.”

If you were to look at “Life After Dark” as a book about music, you’d miss be totally missing the bigger picture of what Haslam has tried to do here. He focuses in on the individual’s role, but also how they interact with a community: how the individual is affected by those around them in terms of attitude, interests and fashion. He knew this from the beginning and it helped shape the tone and structure of the entire book.

“I wasn’t just writing a book about music. I was writing a book about fashion, and ideas, and identity, and how those have all changed through the years,” he says. “If you take a big perspective, like I have, you realise that in the 1920s, people were criticising the way women dressed to go out. They were saying that the dresses were too high, or that the lipstick was too bright, or the Jazz music was too weird.”

“Life After Dark” looks at clubbing in such a unique light. Haslam looks at the history of our clubbing patterns from an almost academic way, but through DJing for so many years, he’s able to bring the human element to the front. It’s about the people passing notes to the DJ booth and the people taking those memories away with them. It makes you question your own views on going out, but also reaffirms a lot of what you already thought. It makes you want to stay in reading it, but also makes you want to just go the fuck out this weekend. If, as Haslam says, “Nightlife gives you life” is true, we should all start living much more before we lose another 1,411 places to express our identities.