How to stay sane while making your own music

- Text by Cyrus Shahrad (Introduction by Biju Belinky)

- Illustrations by Laurene Boglio

Cyrus Shahrad is a communicator at heart. A writer and journalist by trade with a longstanding fascination in films, he spends part of his time creating ethereal electronic music under the moniker Hiatus – a project which serves as a way to address the complexities of being alive. Matters of loss, heritage, melancholia and nostalgia are all expressed within strong beats and soothing piano crescendos.

In his music, Cyrus doesn’t rely just on words to convey emotions and feelings – he finds them restrictive when they’re the only tool in the box. Instead he prefers to harness the power of sounds – both modern and classical – meshed with a sense of surrealism that’s to be expected of an avid David Lynch fan.

The South Londoner’s tracks stem from a place that’s very personal – a universal emotional landscape steeped in worry and grief.

“I’ve always taken inspiration from a nebulous feeling of the immensity of existence,” says Cyrus, “the sense of life as a finite window on to an infinite universe – and the idea that art of any sort can be an attempt to make sense of the inexplicable mysteries that surround us.”

“Less generally, I’m inspired by memory, and nostalgia, and the tension between innocence and experience – all ideas that come together neatly in the idea of Iran, which is one of my greatest inspirations.”

In his most recent work, All The Troubled Hearts, Cyrus’ creative process was inspired and informed by his Iranian father, the album featuring the wisdom of Persian poems he’d heard recited at the family dinner table throughout childhood. Some of these very poems are heard in the background of tracks, spoken by Dad himself.

Ultimately Cyrus sees sounds as another tool of communication: a way to reach out and offer a sense of belonging, sharing the burdens of life – an aspect of making music he finds solace in time and again.

But just like any creator that has been at it for some time, Cyrus knows very well that the music making process is a double-edged sword: it might fuel you and be incredibly rewarding, but it might also end up throwing you into a vortex of frustration and self-doubt. Over time he’s learnt to push through the fog and continue creating, and there are lessons he’s learnt that could help us all on the way.

There is no such thing as perfection in art

My first English teacher told me: a poem is never finished, only abandoned. Any music producer with obsessive tendencies knows how hard it is to stop making tweaks and accept that a track is ready for release. Part of that is a fear that people aren’t going to like it; a bigger problem for me is the belief that if I work on something long enough, I can make it perfect. That’s the single most dangerous illusion in the world of art, I think.

Every album I’ve made has caused a minor breakdown – I spent nine months mixing the last one at my parents’ house in an attempt to mitigate the madness of studio isolation – and the temptation to keep tweaking tracks makes me ill with worry. Ironically, the process of erasing ‘mistakes’ in music eventually becomes the process of erasing yourself from the work. When I listen to older tracks of mine, I actually cherish the flaws in the mixes; they’re like photographs of a younger me falling unexpectedly from the pages of a book.

Creativity is not a computer program. Your heart is not a hard drive

I never studied music production – I started playing with Reason while working as a journalist in the early 2000s – and I still don’t know how 99% of plugins work, choosing instead to stick to a few basic applications and moving knobs and faders until things sound the way I want them to. For years I felt ashamed when people asked me about saturation and sidechain compression, and I still wish I had a better grasp of the technicalities of music production, just as I wish I could read and write sheet music. But I’ve come to realise that creativity and technical prowess are different things – there are people who write amazing music, and people who make music sound amazing.

Every so often you find someone who sits at the centre of the Venn diagram – Jon Hopkins, for example – and it’s hard not to envy them. But most of us exist on one side of the divide, and given the choice I’d rather be someone with music in their bones than a basement full of equipment. I did rent a studio for a while, but all three albums were mixed on a laptop, in a bedroom, with a pair of Rokit 6 speakers. No amount of cutting edge gear or copies of Sound On Sound magazine can make up for a lack of musical intuition; that said, no amount of musical intuition can stop your music sounding shit on a big system.

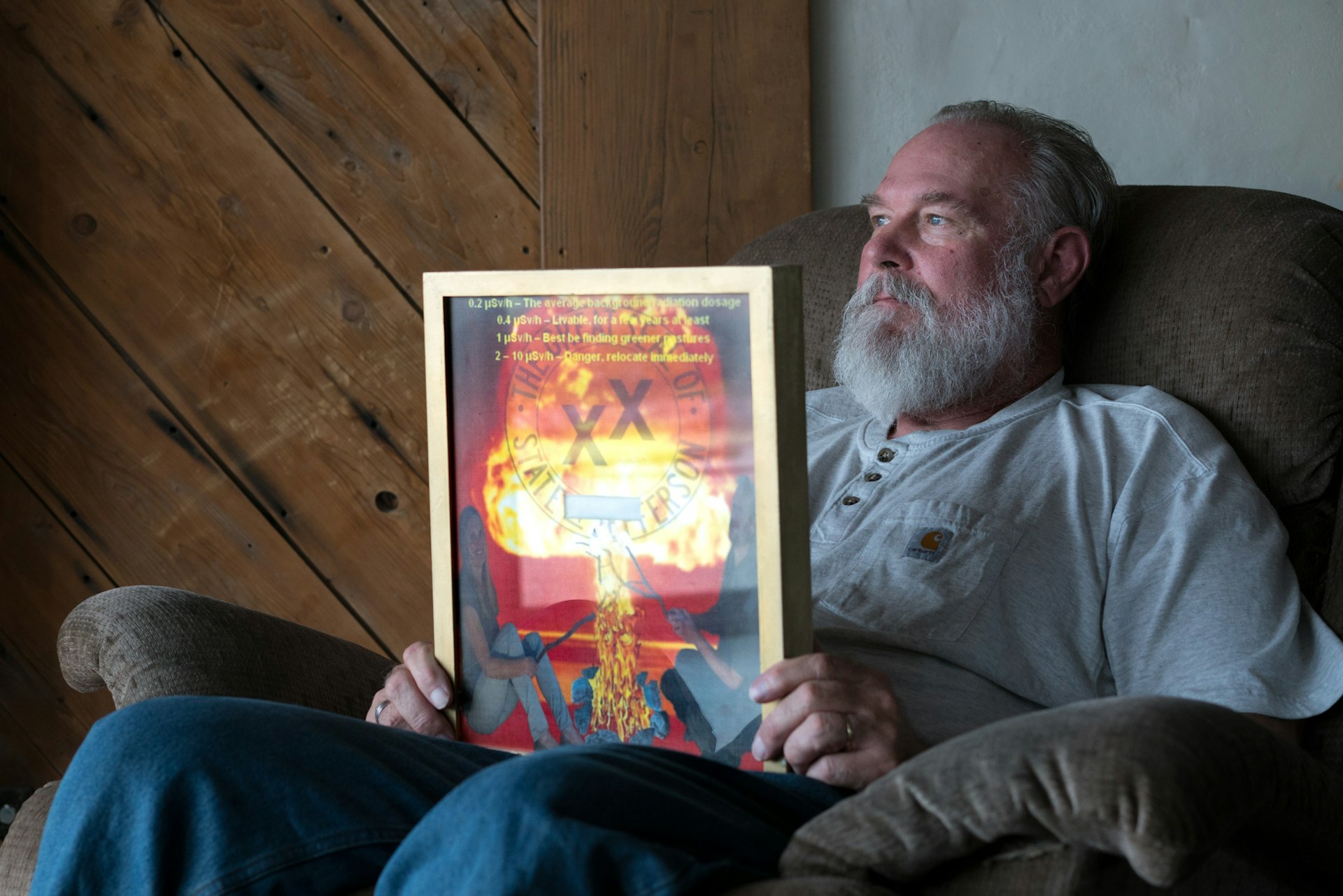

Cyrus Shahrad

Take a break and engage with the world

It used to amaze me how, after hours of banging my head against a musical brick wall, I’d drag myself outside for a walk and the solution would suddenly present itself, and I’d find myself humming an idea into my phone and sprinting home to record it. Perhaps I shouldn’t have been surprised: in all areas of life, those eureka moments seldom occur when we’re staring at the thing that’s ensnared us, and it’s important to know when to turn off the computer and step away so that we can see the wood for the trees.

Last year I took that a stage further, and began teaching English part time at a school in north London. Creativity is like a fire, and to keep the fire burning you need to occasionally head out into the world to collect fuel – to engage with people and collect stories that inspire you to make art. Otherwise you end up running on fumes, and your work starts to feel stale and recycled.

If you’re sending your music to people for advice, know why you’re doing it

When I started making music I would send tracks to twenty or thirty friends, most of whom had no background in music, then find myself in a panic as I tried to reconcile their conflicting opinions. At the other end of the scale, I know someone who spent years working on a novel without letting anyone read a single line. Neither approach is healthy: if we refuse feedback of any sort, we risk following the wrong road and creating art that no one but ourselves could possibly have any interest in; if we try taking on board too many opinions, we risk losing the road altogether.

Over the years I’ve come to rely on a few people whose opinions I value, and I send them tracks at a point when they’re still embryonic enough for me to make changes without breaking my heart. It’s a wonderful feeling when someone suggests an alteration and you know that they’re right; at the same time, you should have the courage to ignore their advice when you think they’re wrong. Ultimately, I try to remember something my friend Matt Falloon once told me: it’s better to have some people love your music and a few people hate it than everyone think it’s quite nice.

Look after your hearing

I didn’t, and now I have tinnitus, and can’t sleep without white noise to cancel out the constant ringing in my ears. If you’re a gig-goer or DJ, wear earplugs – the custom moulded ones seem expensive, but they’re the best investment I ever made (and are much cheaper if you’re a member of the Musicians’ Union). Producing music with hearing problems is like playing the piano with fingers missing – it’s not impossible, but why make things harder for yourself? Keep your speakers at reasonable levels, avoid mixing on headphones, and get your hearing tested regularly. Your music may be in your head or in your heart, but it’s your hearing that will bring it to life for others.

Be kind to yourself

For all the stereotypes of the art life as one long bohemian beano, it’s hard being an artist. If you’re still doing it in your thirties, then chances are you’ll be doing it for the rest of your life, and that’s a burden as well as a blessing. For me, music and writing are ways of reflecting on the mysteries of existence, of making some sense of our momentary window onto the seemingly endless expanses of time and space; they also help me deal with the ups and downs of life on earth, its loves and losses, its beauty and brutality. But that comes at a cost; the art life can be isolating, and if you’re prone to periods of depression, then the times when it’s not going well can be incredibly bleak.

So take it easy on yourself. If you’re going to suffer from OCD tendencies no matter what, then accept that that’s simply how you make music, and work on damage limitation – I find that knowing how my brain works, and recognising when it’s laying traps for me, helps lessen the misery when I fall into those traps. Daily exercise makes a big difference, as does meditation; eat well, and avoid thinking that drink or drugs will help you make better music, because they won’t. Also, it’s hard when your studio is in your home, but try to separate your music from your personal life, and make sure you don’t end up eating breakfast in front of the speakers or mixing until it’s time for bed.

Most importantly, when things are getting heavy, remember to talk to friends or family. It can sometimes feel like we’re not making good music unless we’re absolutely miserable; I’m still not convinced that isn’t the case, but I’m trying not to suffer in silence anymore.

Listen to Hiatus’ latest album, All The Troubled Hearts, or learn more about Cyrus on his website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.