The evolution of Georgia Anne Muldrow, supersonic innovator

- Text by Cian Traynor

- Photography by Mikayla Whitmore

Georgia Anne Muldrow has a way of making people think she’s from another planet. Her ability to craft a left-field blend of funk, jazz and R&B has brought all sorts of talent into her orbit – from Erykah Badu and Madlib to Blood Orange and Aloe Blacc – over the span of 17 albums.

The results sound so forward-thinking, so enriched with far-flung ideas that people tend to reach for words like ‘cosmic’ or ‘epic’ in the hope that you’ll somehow get the picture. Yasiin Bey (better known as Mos Def) once likened her to some of the greatest singers in history, telling the New York Times: “She’s like religion. It’s heavy, vibrational music. I’ve never heard a human being sing like this.”

“People just eat that quote up,” says Georgia, breaking into a laugh so warm that hearing it feels like a hug. “I’m thankful that he sees it that way but, man, I don’t know what he’s talkin’ about!”

The 35-year-old is speaking on the phone at home in a quiet cul-de-sac on the outskirts of Las Vegas, the expanse of Nevada’s desert looming nearby. As she describes the room, her voice is smooth and mellow, her manner slightly guarded but still exuding intimacy.

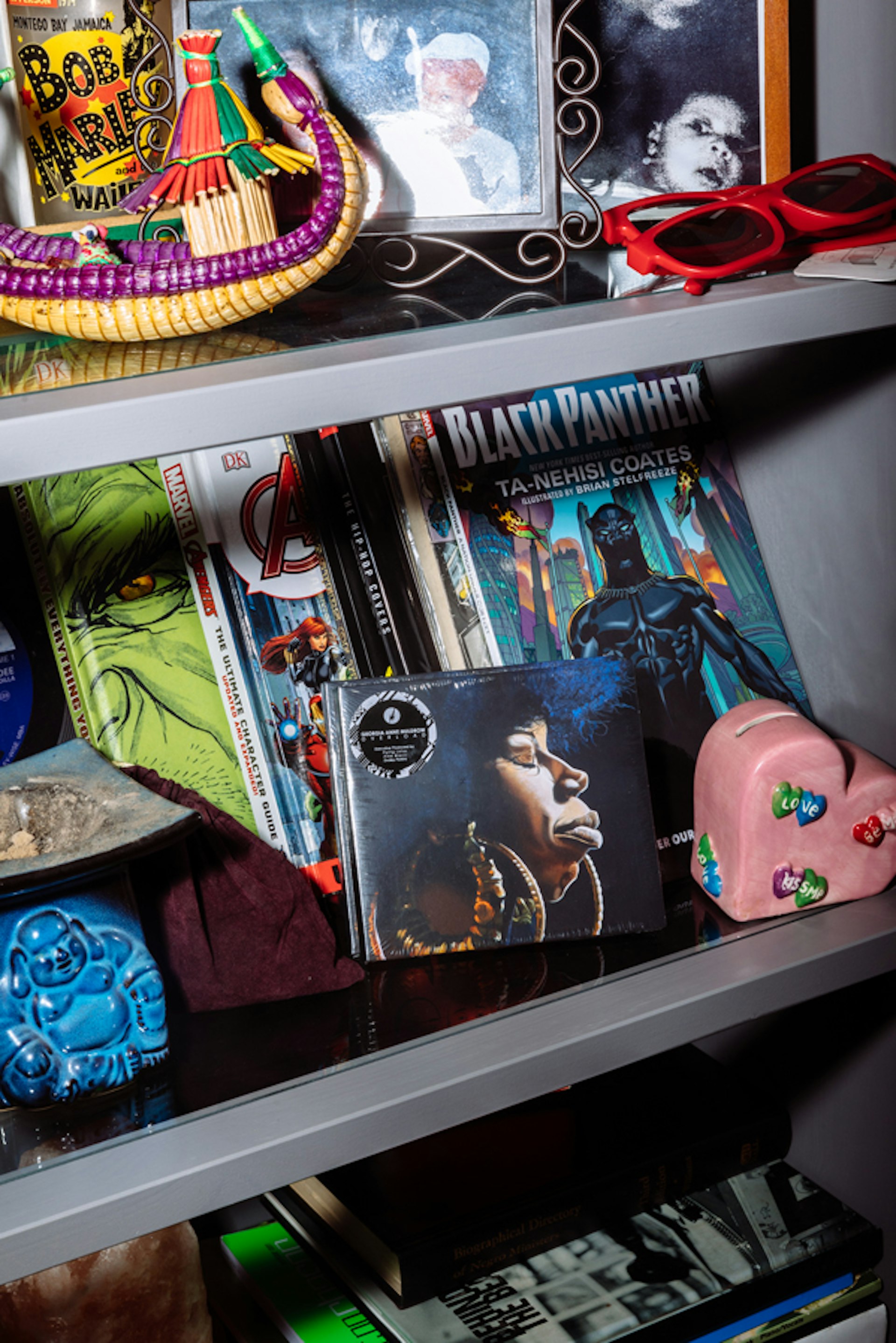

The shelves beside her hold various spiritual paraphernalia – an amethyst crystal, a smudge stick of sage, pieces of palo santo – alongside mementos from a career that would be best described as daring.

“Some people want to get signed to a major label because they feel like that’s the only way that they can be successful,” she says. “But I was never afraid to be independent. I knew the kind of music I was making was different and that it wouldn’t be understood right away.”

Growing up in LA, Georgia was shaped by a seriously musical household. Her mother (a singer) worked with jazz icons like Pharoah Sanders; similarly, her father (a guitarist) played with Eddie Harris and Maceo Parker. Together they recorded the 1982 hit ‘She Can’t Love You’ as Chemise.

Their daughter became “obnoxiously in love with music”, concocting beats on any surface, taking lyrics from every street sign she passed, curling up beneath the family piano just to take comfort in its vibrations.

“When I said, ‘I don’t want to go to school, I just want to be a professional musician,’ my mom felt it because she was always independent, too,” says Georgia. I grew up watching her be her own label and she pressed up my first CDs, so it was incredible that she believed in me at a time when I didn’t believe in myself, when I just wanted to make music to get my feelings out.”

In her late teens, Georgia poured so much energy into songwriting that a stint studying jazz in New York put her on the fast-track to burnout. She felt that if she wasn’t constantly creating, she didn’t matter as a person.

But a move back home to LA allowed Georgia to recalibrate and make music at a healthier pace.

“In the Zulu tradition, they say that every true artist has a breakdown. The way you come through that and heal is how you become the artist you’re supposed to be. I definitely had that cocoon phase of totally breaking down and becoming something else. The same bits and pieces of what I was before [were still there], but I think something within me started to align.”

One night in 2005, Georgia was invited to a show by Peanut Butter Wolf, who would sign her to his label Stones Throw. But the lasting impact of that encounter was an introduction to her future husband.

Georgia arrived late, walking in wearing African fabrics and with electrical tape on her shoes, just as the rapper Dudley Perkins was about to come off stage. She noticed a “silver oval light” around him that felt like a sign of some kind. The pair soon got talking, forming a connection that’s kept them together ever since.

Dudley and Georgia are both studio heads, both believers that music can serve a higher purpose. Together they would tour constantly, feeding each other’s creativity (Dudley is detail-oriented, Georgia is driven by instinct). At one point they moved to South London, then retreated to the Santa Monica mountains, forming their own label (SomeOthaShip Connect) along the way.

Looking back now, Georgia’s memories of that period seem clouded by drink and smoke – an attempt to overcome the “negative self talk” within. Eventually the pair decided to give up alcohol, become vegans and raise their young family in Vegas, all while developing a sound that felt true to their worldview.

Asked how she think her music has evolved over the years, Georgia compares it to watching a baby learn how to walk. “There’ll be one time when the baby runs and you’ll be like, ‘Oh my God!’ Then another day they’ll be like, ‘Nah, I still want to crawl.’

“That’s what it sounds like to me: a human being growing up. All the angst, the anger… trying to find a way to deal with all that stuff. Thank God I found a way to become a mother and really work out all those issues.”

Seventeen releases later, Georgia can sometimes still feel as sensitive as that sleep-deprived 18-year-old trying to keep up with herself in New York. New album Overload represents a career-best – pop-focused yet still unpredictable – but it’s also a product of world weariness.

The year 2019 once sounded so far-off and futuristic, she says, yet we keep seeing the same cycles of abuse being perpetuated – whether it’s through politics or corporate power.

“Sometimes the weight of the world can be so heavy that I forget how much my love of music is. Then I’ll stop making it for a while and wonder why I’m upset. I just want my music to help make somebody happy about themselves – which is a form of resistance in itself – so that they can fight another day.”

This is where timing plays a part. There were points, Georgia admits, when she did find it difficult to be considered so different, appreciated only in certain circles.

But in recent years the likes of Kendrick Lamar, as well as Georgia’s Brainfeeder labelmates Kamasi Washington and Thundercat, have helped listeners reimagine what jazz can be, popularising a more avant-garde approach.

“I’m just happy that more people can dig it,” she says. “Maybe I helped them find a way to give language to what they wanted to bring together, but it was already alive in them. I wasn’t doing Thundercat’s practice scales for him. Everybody’s doing their own work, you feel me?

“But when I hear something that’s familiar, I see it as a nod. Like, ‘Right on!’ That’s what you do in jazz: you quote other people.”

She pauses for a beat. “It does feel like I’m not alone no more. For a minute there it was just like, ‘What are you singing?’ I got laughed at a lot. It took a long time for people to take me seriously. But the deal is you’ve got to keep on being yourself; you’ve got to take a chance on keeping it real.”

Overload is out on Brainfeeder.

This article appears in Huck: The Flying Lotus Issue. Buy it in the Huck shop or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.