Stone Roses Gig: 25th anniversary of a seminal moment in rave culture

- Text by Michael Fordham

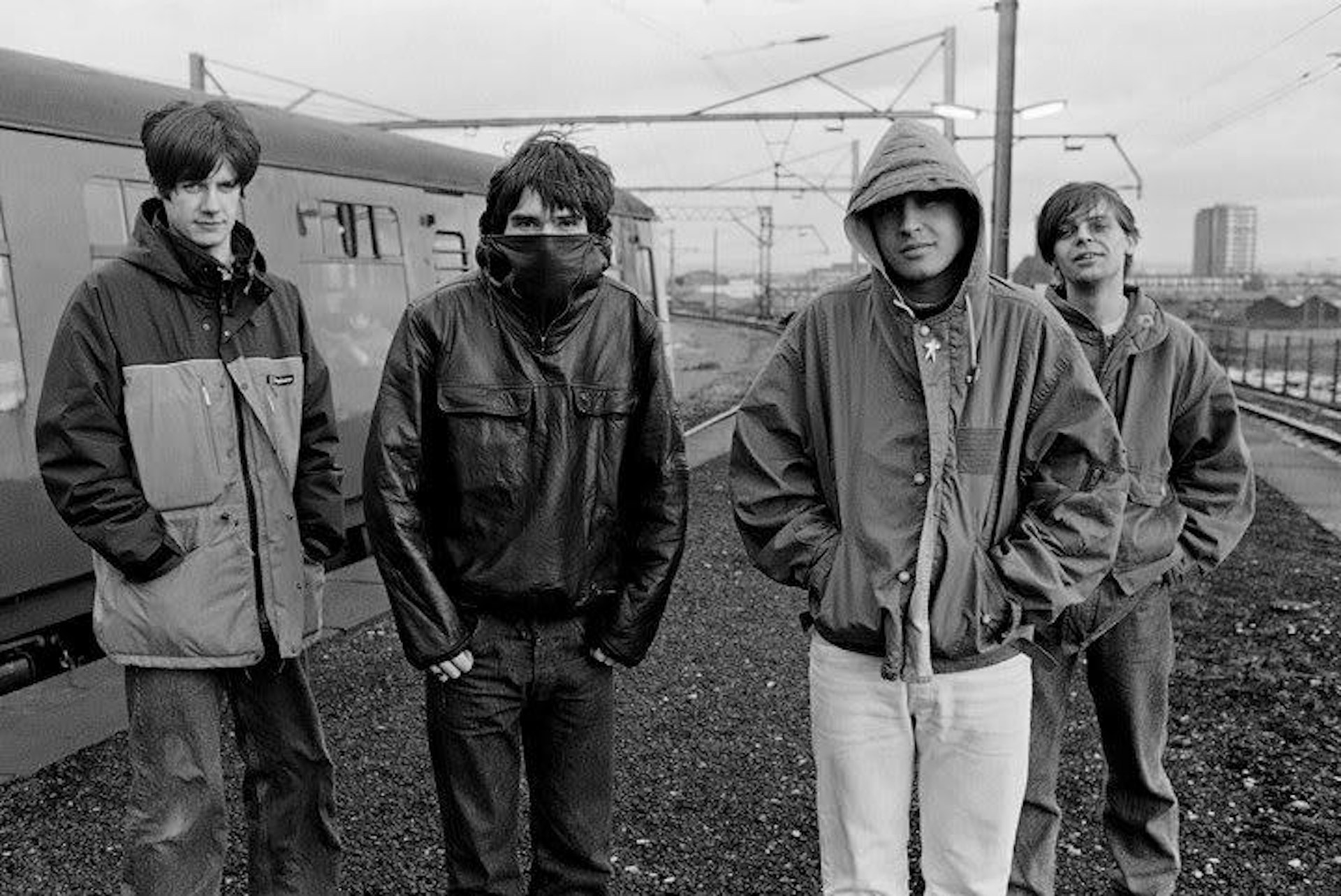

Ian Brown looked into the camera and poured himself some mineral water. There he was, the simian monarch understated, dread in the maw of the lens but lithe and calm and bantering at ease with the gathered hacks. Mani had been instigator of the reunion – facilitator of the definitive Brown/Squire entente, which had ultimately bought the Stone Roses back together. Manic and Benson-throated and scooped out, he was decked out in a LVC suede trucker and Engineered Garments floral print shirt. But before he’d even opened his mouth that face had whispered most eloquently of the time that had passed. Squire held himself with that distinct Squirism that hadn’t changed a bit – a Lennonesque mix of pisstaking and deadly earnestness that only true working class heroes can pull off. And Reni. Reni was a piece of work – twenty five years ago you only saw him hunched over the kit, his face obscured by the brim of his titfer, peppering out those polyrhythms, digging manically the foundations of the Roses’ sound as if nothing else mattered in the world. Here he came across like a fully paid up, tax returned subscriber to Martin’s Money Tips, amazed and quietly amused in his salt and peppered maturity, that he was ever there at all.

In the early spring of 1990 The Roses had announced what was to be their definitive, above-the-radar gig. It was to be held at an acreage of post-industrial wasteland stuck out in the Mersey Estuary. At that precise moment we chirpy cockneys had been fully eighteen months into a chemical saturated cultural revolution, one that we believed to be our own. It certainly excluded anything north of Watford. Spike Island? Widnes? As far as we were concerned these were just arcane syllables, vaguely industrial sounding and distastefully redolent of Rugby League. The North? That was a place that existed only to be sneered at! We were, therefore, more than a little wary of rocking up and representing in the Northlands for the Roses gig. But we stronged it out and went anyway.

Our collective memory of Manchester and other northern environs had after all been informed by the decade that had recently come and gone. And the only reason we left London in those days was for a day out flaunting ourselves and our clobber at the Football. We had been reared on the buzz of an early Inter City 125 and a day milling about avoiding cockney hating coppers and cadres of outriding likely lads who could spot our East London-ness a mile off. It was after all a genetic disposition that expressed itself in the donning Italian sportswear levened by the Saville-row-wrought nods to class disjuncture, not to mention the sovereign clad fingers in the jean pocket and the bowl with a wide kneed flick. And let’s not forget the hard edged syllables that would creep out beneath our bowl wedges about how, with every click and clack of the northerly heading train track, that this England had become a little less pukka. Little wonder they hated us.

Though rumour had it that up in Manchester a system of cultural artefacts was revolving around a place called the Hacienda, we were convinced that this was little more than a skilful piece of myth making on behalf of them northern monkeys. This was our ersatz understanding of history – a distorted semiotics of place and difference that convinced us that we, as denizens of the eastern tributaries of the Thames, from where empire was launched and modern civilisation came to be (for fuck’s sake!) were natural heirs to the glory of England. It didn’t even occur to us that there was another centre of its own English universe wrought in brick and stone and satanic mill, a place where the industrial revolution was sparked. We’d rock up, We’d take the piss. That’s what it was all about.

It was no longer cool, meanwhile, in the wretched afterglow of Heysel, Bradford and Hillsborough to be a football fan – and thus a key bastion of working class swagger had been overrun – yet to be replaced by the prawn sandwich munching battalions that marched under the banner of Gazza’s tawdry tears that summer in Italy.

The Tory government sustained and polarising assault on all things rooted in the factory floor had seen to this swing away from all that was authentically proletarian, all that reeked of that hat-on-the-side-of- the-head bravado of the working man. But rather than melt into to the background and get a respectable job in insurance, the top boys in the South East with their eye for a well-turned collar and well-turned pound note had embraced the new creed and had reinvented themselves as pioneers of a pie-eyed sort of entrepreneurialism. It was just a new, more profitable way of taking the piss. Now everyone and their little brother, Millwall scum from the wrong end of the Old Kent Road to Under Five rapscallion from Plaistow – were cuddling each other in the warehouses and abandoned airfields around the M25. So by the time Spike Island came around we usually watched the match though the hazy gauze of a spliff soothed come down. This of course tended to de-claw the sting of battle and blur the lines nicely.

The Stone Roses – the way they held themselves as well as the music – had etched its way into our addled consciousness despite the geographic displacement. Despite surface aesthetic appearances, the Roses sound was rooted in the same earth – be it the sludge of Southport or the tidal flats of Caister. For a brief moment the tribalism of north and south, soul boy and scally, disappeared and was revealed in its righteous anachronism. There was affinity between the music and the attitude, the aesthetic and the politics – something of that time honoured fuck you that transcended imagined boundaries within the working class defined by geography, togged-up territorialism and the beautiful game.

It didn’t matter that the Spike Island gig was a badly organised shambles with a sound system that couldn’t have satisfied a warehouse full of pilled up Essex boys. But at that beautiful moment the Roses represented the last gasp of thinking prole attitude – and one that swashbuckled with abandon all over a Britain that was changing fast.

At Spike Island the twisted histories of working class culture came together. Those elements can probably never fuse again. The world turns. Times change. Class means other things these days. Good music remains good music, no matter what shackles it to the earth.