The Cameroonian inmates who made an album behind bars

- Text by Thomas Hobbs

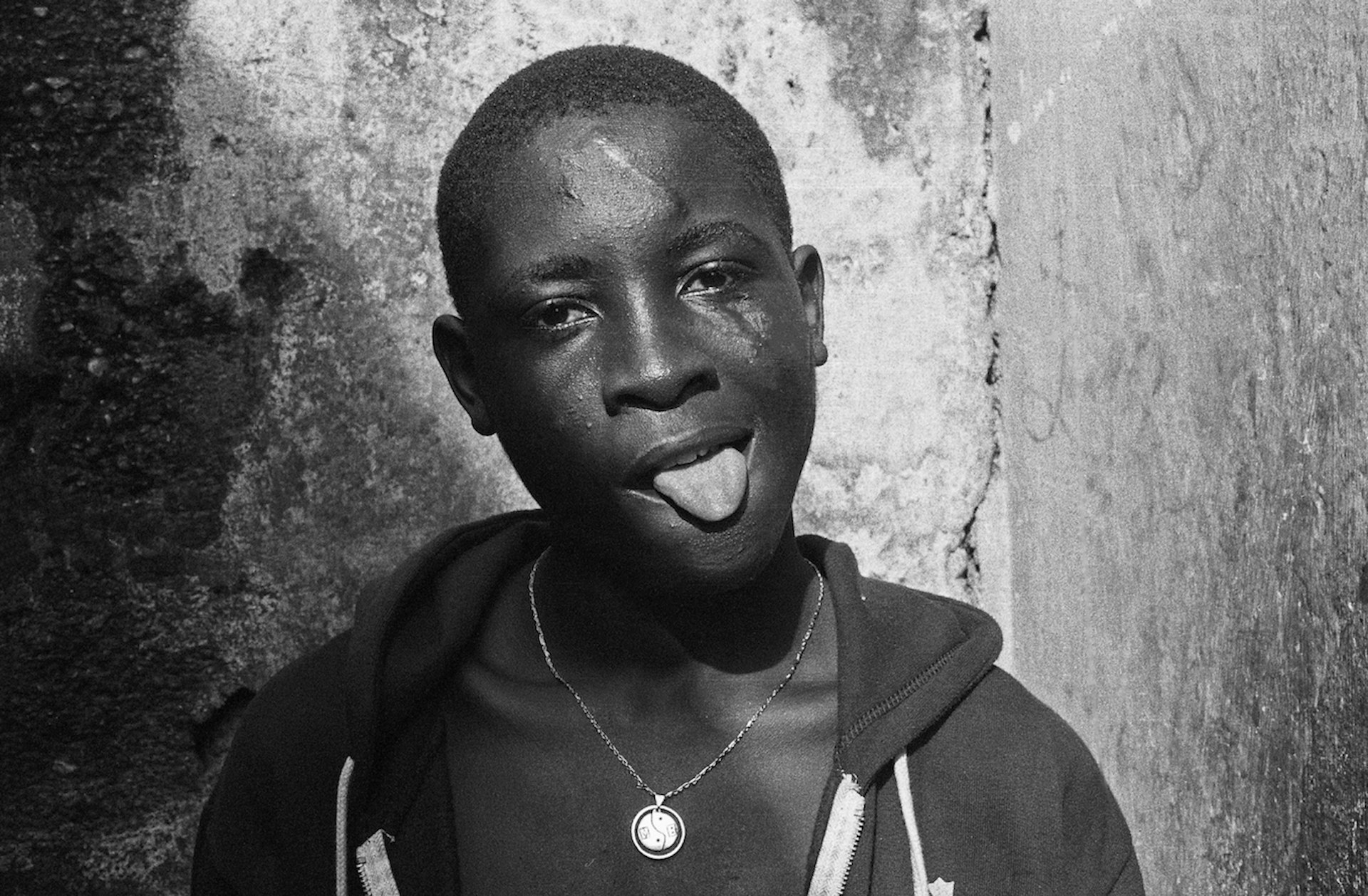

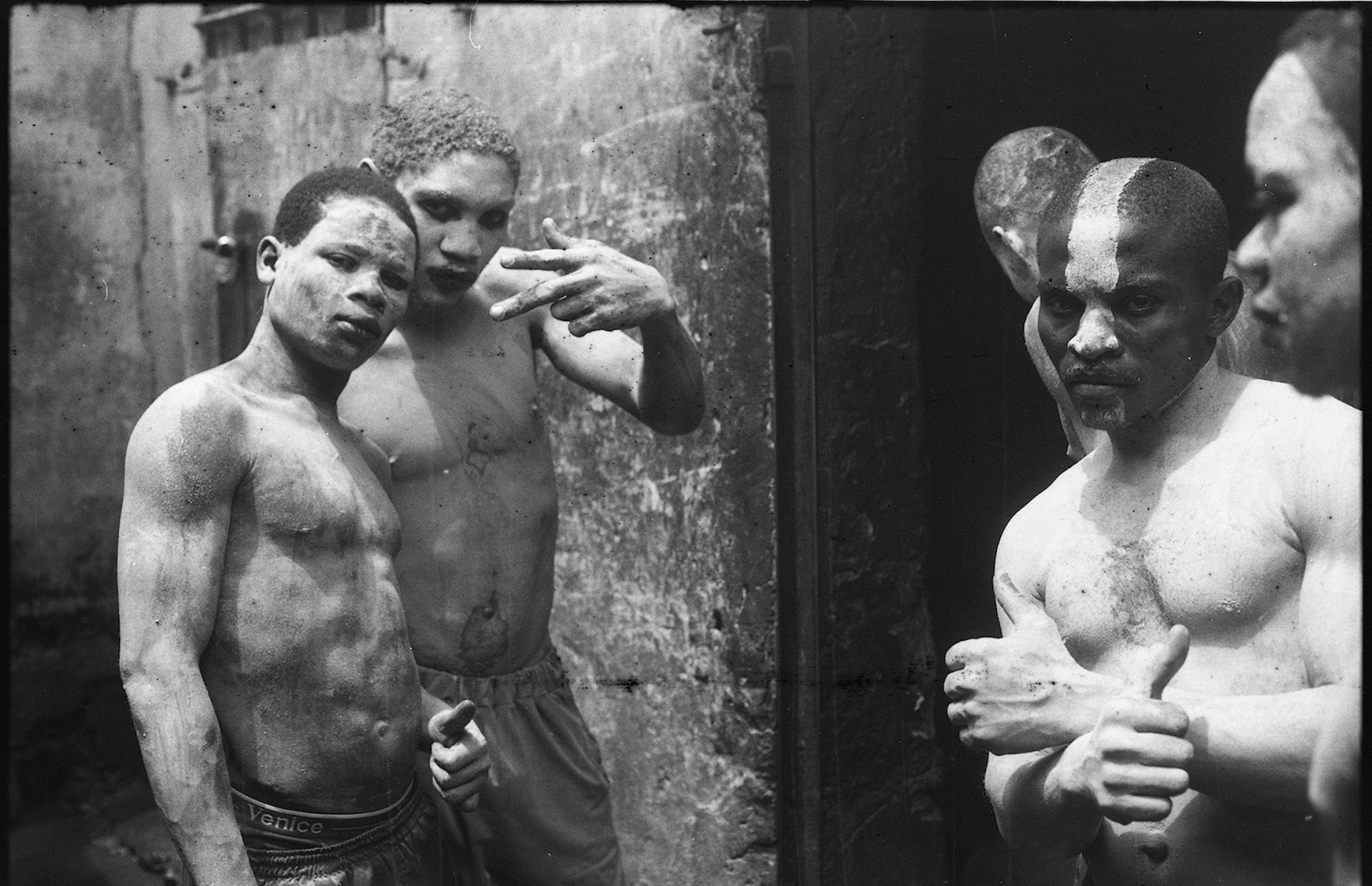

- Photography by courtesy Dione Roach

“There’s a lot of pain in there,” says Dione Roach, an artist and teacher who opened a recording studio within Cameroon’s Douala Central Prison back in 2018. “So many of the inmates are addicted to drugs and cramped in these big communal cells, so that obviously creates a lot of dangers… You have murderers next to people who just stole an apple. The energy is very unpredictable. In ways, it feels more like a refugee camp than a prison.”

The idea of opening a recording studio within an African prison might sound far-fetched. However, having persuaded the Douala prison authority that creativity could be a positive way to help its prisoners in their rehabilitation, Roach achieved just that through her charity work with the Centro Orientamento Educativo (COE).

“I just sensed that these guys needed a creative outlet,” she explains. After COE funded studio equipment, Roach largely took a backseat role, letting the prisoners control their own destiny. She asked producer Steve Happi – who assembled a crew of talented inmates for recording sessions – to control the space and make the most out of all the instruments. (Happi energetically played just about everything himself).

“There’s a stigma around going to prison in Cameroon,” Happi – who was sent to prison in 2018 for murder but is now free after clearing his name – tells me. “When you leave prison, people automatically think you are a loser. Having this studio let us express a lot of pain that was buried in our minds. A lot of people don’t want prisoners to speak out, but this was a chance for prisoners to share their truth and to feel important [for a change].”

The resulting record, Jail Time Vol. 1, which is credited to Jail Time Records and is being released independently through the efforts of Roach, certainly lives up to Happi’s description. A mixture of French and English-speaking songs, it’s a raw insight into the minds of some of Cameroon’s most forgotten citizens, moving between trap, boom-bap, dancehall and pop with an urgency that tells you these artists were putting absolutely everything they had into the music.

‘I go round in circles but my thoughts are square,’ spits prisoner D.O.X. on confessional highlight, ‘Offline’. It’s a powerful double entendre that shows how prison conditions your mental health to take the same shape as the cell you’re forced to sleep in, night after night.

Petit Batonette, a refugee from the Central African Republic who fled from civil war yet ended up homeless in Cameroon, displays haunting bluesy vocals on gorgeous closer, ‘Bibi’. It’s easily the album’s most transcendent moment, with Happi telling me that the singer, who was jailed for his alleged role in a money detournement issue, wanted to find a way to turn the tragedy of his life into a melody that could persevere and still find a way to sound beautiful.

“Petit is showing there’s light inside this prison if you look hard enough,” says Happi. Meanwhile, trap anthem ‘Ma Plume’, which features D.O.X and Stone – a government soldier from the Francophone region who fought against Boko Haram before dissenting and turning to robberies after struggling to make end’s meet – contains the project’s mission statement. ‘The life of the ghetto and its misfortunes / all these massacres and fights / we’re just looking for peace of heart,’ raps Stone like a world-weary street prophet, his voice weighted in scratchy emotion, imparting the sense he’s still tormented by the things he saw on the road. That he still wants to fight for inner peace is inspiring, and hard to stop thinking about.

Stone’s lyrics speak to the danger and division that exists at the heart of Cameroon society. The ongoing Anglophone Crisis has seen the African country’s French-speaking government aggressively deal with a so-called revolution among its English-speaking citizens, who make up around 20 per cent of the country. Hundreds have been killed as a result of the conflict and more than half a million people displaced from their homes.

Cameroon’s problems are a consequence of France and Britain dividing the territory up after seizing control from Germany after the First World War ended. By 1960, the French-speaking side won independence, establishing a new nation in the La République du Cameroun that aimed to unite the different factions. But this didn’t exactly come to fruition, and the 35-year rule of the country’s current leader Paul Biya has been sullied by allegations of corruption and human rights violations.

This backdrop is why such a rich feeling of revolution fuels the prisoners’ music. One of the project’s most technical emcees, Do Stylo, refers to being “surrounded by death” and feeling disillusioned by the government. ‘All those illusions they try to make you believe in / they’re full of spells,’ he raps defiantly.

“Do Stylo is talking about how historically, Western people come to African and exploit our land,” says Happi when asked if some of the anger on the project could be a response to the ugliness of colonialism. He reminds me that Douala – which is home to the prison but also Central Africa’s largest port – was one of the main locations where European merchants sold African slaves to Americans.

“The verses on this record reference how politicians have long been complicit in selling off Cameroon [to outsiders] while still letting their own people suffer. Remember, even the name Cameroon is Portuguese. It refers to the shrimps they found in our rivers, which means we didn’t even get to choose our own name! Some of the artists on this album are presenting a bit of a mental awakening.”

The creation of this album has undoubtedly helped the prisoners, giving them more of a purpose. However, the promise of a better life that music offers inmates has not always lived up to the reality beyond the prison. “Already two of the artists, Quimico and Vankings, have died,” says Roach. “They were released and caught stealing. They were then just murdered in the street. It shows how hard it is to get opportunities when you’re out. Sometimes it’s harder outside of prison than it is inside.”

“Vankings and Quimico’s voices will live on forever through this project, and that’s a beautiful thing,” adds Roach, recalling Vankings’ “infectious energy” on the track, ‘Mickey Mouse’, which more than deserves to be a hit single. “Remember, these songs are a window into the lives of people you rarely hear from.”

In 2018, Cameroon’s Anti-Drug National Committee estimated 60 per cent of its citizens aged between 20 and 25 had a problem with hard drugs such as crack. “It’s a big problem,” claims Happi. “The lack of opportunity fuels drug use. We want to say with this project that you can hit rock bottom and still find light. A lot of the artists who contributed had a drug problem, but they found the strength to make these songs.”

Looking ahead to the future, Roach says she wants to try to open up more recording studios across African prisons and take the artists who contributed to Jail Time Vol. 1 on a global tour. There’s also plans to make a documentary about their story, but these have since been delayed due to COVID-19 restrictions.

Happi just hopes the album will make people empathise with Cameroon’s criminals and realise that they are human beings who deserve love. “The artists you hear on this album have all had terrible difficulties in their lives,” he concludes. “If they can make even one person feel something in their heart with this music then that’s a beautiful thing. It means we did our job properly.”

Jail Time Vol. 1 will be released independently in January 2021.

Follow Thomas Hobbs on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.