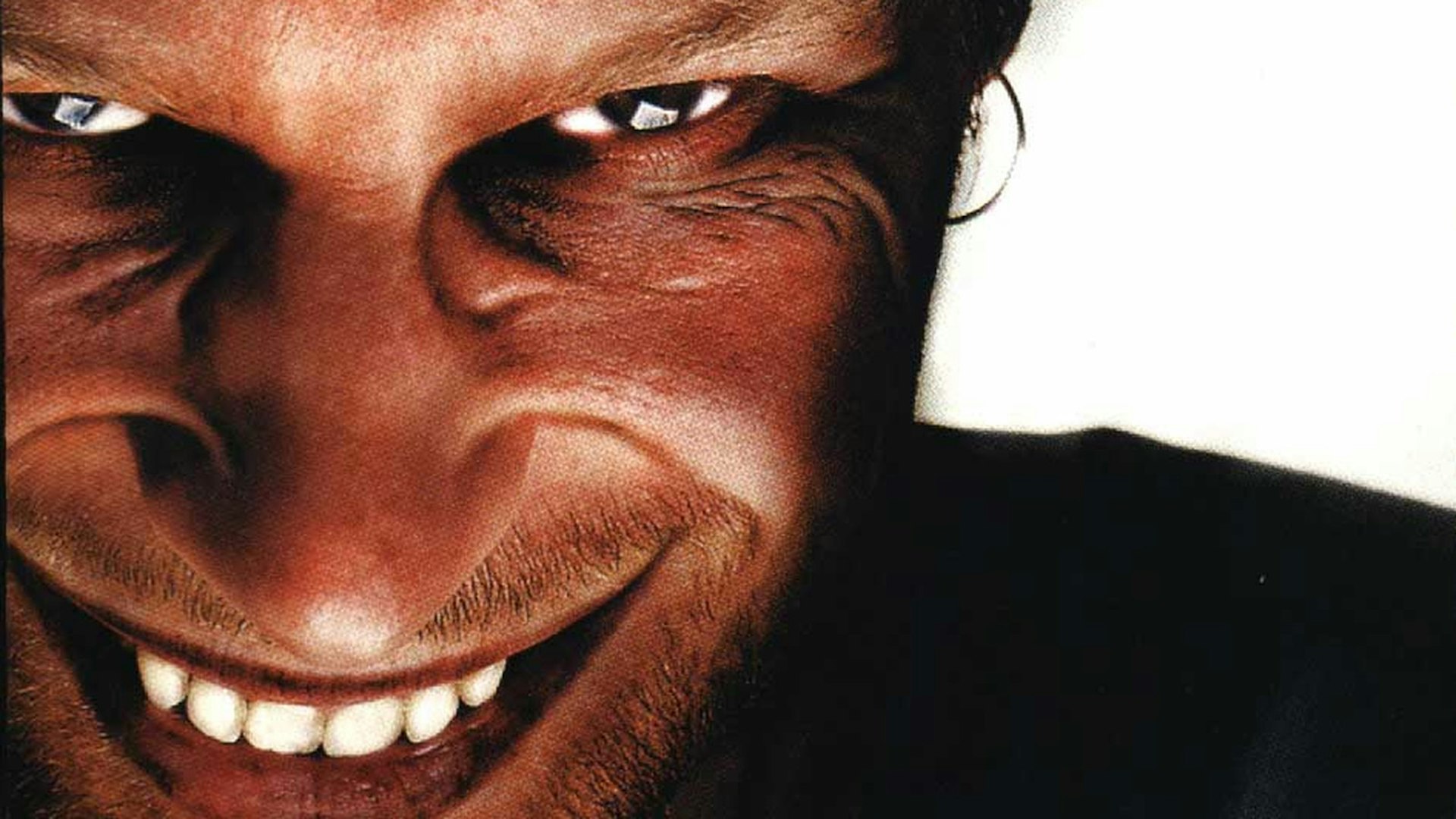

The mad extraterrestrial power of Aphex Twin

- Text by Seamas O'Reilly

- Photography by Warp Records

The music I heard in my childhood was not a direct route to Aphex Twin since I was, unfortunately, raised in and around the poisonous world of Northern Irish country music. After its brutal history of startling internecine violence, Northern Irish country music is the thing for which my homeland should be most ashamed.

As its name suggests, NICM (acronym my own) is little more than American country music sung by people from Ireland’s northern counties. For reasons thus far ignored by learned men, a lot of rural Irish people are fond of American country music. Unfortunately, they took it upon themselves to construct this music at home for themselves, complete with plaid shirts, cowboy boots and songs about dive saloons, prairies and trucks. Lads who drive Volvos cosplaying as Mississippi cattle ranchers, not as some sort of fringe cult of laughable eccentrics, but as the most popular musical form in the province. Imagine that Wales’ most popular music was songs about Russian coal-miners, or that the Danes’ favourite genre was folk music centred on the adventures of Indonesian accountants. This, in all its jarring, nonsensical falsity, is the music my father calls his favourite in the world, and it pervaded throughout my childhood.

My father had little time for my attempts to play other music as I grew older, but in fairness, I didn’t make it easy for him. From the age of 10 I became not just fond, but repulsively obsessed with ear-bending electronica that didn’t really meet him halfway. Worst of all was my fondness for Aphex Twin, my father’s bête noire, and my own great white hope.

I first heard Aphex Twin in around 1995, when my brother Dara returned from Glasgow Uni, encumbered with tapes and CDs, large leather jackets and drainpipe-thin corduroy trousers. He’d left 10 years before I would, and had also escaped the plaid claws of country devotion, arriving to a Scottish scene of jangly, self-conscious indie bands, each more fey than the last. I eagerly received these offerings to my barren musical outpost. I admired the sensitive guitar bands he liked, but none of his stuff took root for me until, when I was nine years old, he palmed me a CD that didn’t fit his usual MO; not indie, not even Scottish, but a beige coloured jewel case that bore the legend Classics. It was credited to The Aphex Twin (the definite article being included here for this release).

I played it once and immediately had to play it again, and continued this sequence indefinitely for so long I can’t quite remember. My first obsession was the trickling arpeggio of “Polynomial-C”, with its spiral staircase of major/minor noodling. It sounded regal and pretty and haunting, like a ghost story told by God. Next to fascinate me was the bark dry acid heft of “Digeridoo”, the concrete snap of “Flaphead” and pretty much every single note on the entire record. In other words, this The Aphex Twin lad didn’t sound like anything I’d ever heard before, and I rarely listened to anything else for a little while after.

Soon it was proliferating throughout the house in a way that baffled my dad. He would come in to find me doing homework to “Analogue Bubblebath” or “Girl/Boy Song”, he’d stare at me like I’d chosen to write an essay while gargling battery acid. He’d turn off the CD player at the plug, as if its contagion could infect the mains. He would do this even if he couldn’t hear them from whatever room in the house he was on his way to. My father regarded Aphex Twin as so fundamentally bad that, like anthrax or locusts, he didn’t want them on-premises even if he himself was absent.

That grip of ecstasy I felt hearing Classics made me feel like I was hearing music for the first time; needing to restart a track before it had finished so I could savour the whole thing for a little bit longer, that squeeze of euphoria at rewinding for the dozenth time, all of it was as alien to me as the noises I was hearing. I was struck dumb. It wasn’t until the first glowing embers of the internet came into our home that I was able to source more of his works, propelling myself on a steady journey into the heart of a new, more perfect world. From there I vaulted backwards to the head-opening warmth of “Xtal” and “Ageispolis” on Selected Ambient Works, or the ego-dissolving salve of “Rhubarb” or “Cliffs” from SAW2.

It seemed improbable, rude even, that Richard D. James was so adept at so many different types of music, so capable of creating entirely new forms. And, as a result, it seemed bizarre, even profane, that all my friends were content to hear the same lacklustre radio fare. By the time “Come To Daddy” and, more especially, “Windowlicker” were receiving regular airplay, I was 12-13, and already begrudging the Jonny-come-latelies. I must have been insufferable but I was in love, and still being chased out of the kitchen any time I tried to introduce these sonic weapons into my father’s home.

I dove headlong into his demented fanbase and became one more among the pale, noxious nerds trading thoughts on forums. We swapped mixes and rarities, tried to amass all the lesser-known aliases like Gak, Q-Chastic and Bradley Strider, and sifted through the constant run of fake tracks purporting to be by him, released by sad little guys like us, hoping to get their music heard. In doing so, we all indulged in the same idle fantasy that our passion was causing us to temporarily languish in the company of this cohort of cranks and weirdos, and the unlikely hope that we, and we alone, were the cool one. And there was a lot to discuss, since Aphex was constantly self-mythologising; claiming that he was an avid lucid dreamer, who had a thousand songs lying unreleased, who lived in a roundabout, or maybe a bank vault, drove a tank, was looking to buy a Kosovan submarine, and performed gigs while squeezed inside a wendy house. Some of these turned out to be true, not least when he released more than 250 unreleased tracks to Soundcloud in 2015, just because he could.

When my own personal favourite, the mammoth, 30-track album, Drukqs was released, it proved initially divisive. There were reports he’d only put it out because he lost an MP3 player on a plane and wanted to render the tracks on it less valuable to pirates. Others said it was a prank to get out of his deal with Warp. Spin called it “unimpressive”, Rolling Stone “irrelevant”. I thought it was the greatest thing I’d ever heard, with its titles like wi-fi passwords, and the sheer sonic range of its contents. Here was the personification of a certain type of smart-arsed teenage self-absorption distilled, only married with the greatest musicianship on the planet. The genius of Aphex is that it’s music that can seem alienating, even off-putting, until you find the one of his dozen styles that bites and then he has you in his pulsing, canticle grip.

Bizarrely, considering how volatile it proved for fans and critics, this would be one album my father ever let me play indoors, and not just because he accidentally liked one of its tracks, although that too was the case (as when my sister walked down the aisle to Drukqs’ plaintive, pretty piano piece “Avril 14th”, adapted for harp and violin, and my father mentioned how much he enjoyed it). No, at home it was for another reason. I remember him entering the room as the dense percussive trills of “Cock/ver10” rang out on kitchen speakers, and expecting my father to display horror or alarm at the cacophony afoot. He simply looked blankly from speaker to speaker, and asked “how long does this take?”. It then became clear that he had been presuming the sounds he was hearing were those of Hi-Fi set-up disc, the kind that comes with a CD player so you can test the dynamic range of stereo equipment by playing random cross-frequency noises. Like a Kosovan submarine so old that it couldn’t be detected on US radar, Aphex Twin made sounds so new my dad had failed to recognise it as music. I can think of no greater tribute to his genius than that.

Follow Seamas O’Reilly on Twitter.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.