What kind of future are we hurtling towards?

- Text by Rob Boffard

- Illustrations by Rupert Smissen

– Daniel H. Wilson’s –

Robotic Roller Coaster

Nobody knows robotics like Daniel H. Wilson. Not only does he write novels with titles like Robopocalypse and Robogenesis, but he has a PhD in Robotics from Carnegie Mellon University, plus a few Masters degrees in Artificial Intelligence and Robotics. Without wanting to put too fine a point on it, he’s the most overqualified novelist on the planet.

“I fell in love with computer programming as a kid,” says Wilson. “Creating games and programs was how I expressed myself in the world. But the limitation of computers is that your creations must live behind a screen. Robotics was interesting to me because it offered the possibility of unleashing a creation into the real world! It’s the perfect career for a burgeoning mad scientist.”

Despite the robot-driven apocalyptic nightmare Wilson writes about in his books, he’s curiously upbeat about the future – and about how man and machine can coexist.

Artificial Intelligence

When someone like Stephen Hawking is scared of something, you know you should be worried. Hawking called the development of Artificial Intelligence a potential catastrophe, telling the BBC that it “could spell the end of the human race”.

Wilson isn’t so sure. Despite the presence in his novels of a malevolent AI called Archos (who, by the way, makes for a killer villain), he’s less worried about this than you might think. “I’m a lot more optimistic than Stephen Hawking about the advent of artificial intelligence,” he says. “In a nutshell, it is easier to predict the progress of technology than the social evolution of humankind. Applying radically futuristic technology like AI to our current civilisation could very well be catastrophic, but neglects to consider that human society is actively adapting to the future in ways that are hard to see. For example, think of the predictions in the 1960s of ‘future kitchens’ for housewives who no longer existed after the women’s rights movement. We are on a crazy roller-coaster, but we’re going to be fine.”

Weapons of war

Technology usually gets developed by the military first. Hardly surprising – in places like the US and the UK, this is where the big budgets and the most advanced R&D teams are. With the advent of pilotless drones, it’s an easy mental leap to the idea of autonomous robotic units on the battlefield… right?

“I think it’s incredibly unlikely that the United States will employ fully autonomous weaponry — at least not until some other enemy begins to routinely employ such tactics,” Wilson says. “Instead, within the military there is a huge focus on keeping a human ‘welded’ to the machine, especially machines with lethal capability. What we may very well see, however, are squads or platoons of machines under the control of a single soldier — that’s just efficient.”

Driverless cars

“I’m really looking forward to autonomous vehicles suddenly popping up in traffic,” Wilson says, when we ask him what he’s most excited about in the field of robotics right now. “The zeitgeist is already in motion, with every major car manufacturer seeing the writing on the wall and ready to produce their own versions. Self-driving cars will likely be the first large, autonomous robot that most people will ever interact with — and I think it will fundamentally change the way we think of robots.”

– Nicholas Carr’s –

Cautious Tale of Isolation

Nicholas Carr is the ultimate technological sceptic. He’s made his name writing about the inherent problems he sees with technological advances; his 2010 book The Shallows (which was a Pulitzer Prize finalist) asked pointed questions about what the internet was doing to our brains. He is far from a Luddite – he just has a hard time believing that the outcome of things like social media and Artificial Intelligence are going to be wholly positive. Just ask him his opinion on self-driving cars, which he’s currently working on an essay about: “Every time there’s been a big change in automotive technology, there have been ripple effects, and we don’t tend to think about those changes ahead of time.”

Passing the torch

Carr’s latest book, The Glass Cage, came out in 2014. In it, he explores the potential consequences of what he terms automation: the idea of handing over our jobs and skills and tasks to Artificial Intelligence and robotics. As you can imagine, he’s asking some very big questions.

“I foresee a diminishment in our own capabilities and talents and connections with the world as we become more isolated,” he says, “and as we interact with the world and each other through computer screens rather than directly. We’re going to live less interesting lives, and that manifests everywhere from factories to hospitals to our personal lives where we use Google maps or Facebook when we want to get somewhere or socialise.”

The big problem, as Carr sees it, is that we can get glimpses of the future from what is happening now. “We’re seeing more and more of the automation of professional work,” he says. “Pilots, truck drivers, doctors, architects. More and more jobs are being done with the aid of software and artificial intelligence routines. We don’t see computers able to take over a lot of aspects of analysis and judgement making that we used to think of as our own. We’re constantly negotiating the division of labour between ourselves and our computers, and the way we do that is going to shake everything from the labour market to the quality of our lives as we move forward into the future. We’re so quick to think that all we want is convenience and efficiency that often we just rush to embrace these labour-saving technologies without taking into account that actually enhancing your own skills and facing challenges in our lives are what gives satisfaction.”

What happens next?

It’s easy to accuse Carr of being nothing more than a technological naysayer, but he does raise some worrying points about human interaction. There is no doubt that technology is taking over our lives, in one way or another, and there’s a definite argument that we haven’t been around long enough to appreciate its effects. But does Carr think that there are some potential positives in the future?

He gives a nervous laugh when asked. “I would feel more excited if more of the energy and investment and innovation were going to solving bigger problems,” he says. “Things like water purification or desalination technology – things that are going to address big problems for society in the future. I see a lot of investment going into what I feel are very trivial apps and social media. They have their role, but I wish that the scope of innovation would be much broader.”

He goes on: “There’s this idea that technology and computers will create a kind of utopia on earth, and all our problems, whether it’s traffic or illness or joblessness, will magically be resolved. On the one hand, I’m sceptical about that, because I think they don’t get the complexity of some of those problems, but what bothers me most is that it’s kind of a way to cut off deep discussion of what’s going on today. Saying that computers will solve those problems tomorrow means we don’t have to struggle with them today.”

– N.K. Jemisin’s –

Inclusive Urban Dream

To read an N.K. Jemisin story is to dive into a psychedelic, twisting dreamscape. Literally: in her 2012 fantasy series Dreamblood, nightmares and dreams are things that can be harvested, used, controlled and manipulated. Her fantasy novels (there are five of them) have seen her score nominations and wins for some seriously heavyweight awards, such as the Hugo and the Locus.

The Brooklyn-based Jemisin also dabbles in speculative fiction, particularly in her short stories, each of which are as dark and powerful as a shot of espresso. She is less interested in technology as she is in what will happen to our social structure in the decades to come.

Breaking down barriers

One of the things that Jemisin is most excited about is what she sees as the continuing inroads of marginalised people into wider society. “When I say marginalised people,” she explains, “I include women, I include people of colour, I include people of alternate sexualities and genders. All of that is beginning to be more accepted in life. These groups used to be at the margins of everything: of life, of economics, of power. And that is beginning to change.”

But she certainly doesn’t expect it to be easy. There are plenty of people, she says, who don’t want this to happen. “At one point, I thought Obama had no chance – or rather, I thought that they’d kill him,” she says. “Even if he got elected, I thought he’d be assassinated shortly after, and I think a lot of black folks thought that way. We’ve seen too many examples, and it’s happened too many times historically, where we made two steps forward and one massive step back. I’m looking forward to a world where the power structure begins to reflect the makeup of the world more. I want to see the world look like what it actually is: on TV, in other media, in boardrooms, in parliaments. I want to see people run themselves, instead of being run by a small and powerful minority. When the world is more inclusive, and representative, the world will be a better place.”

The future of cities

Cities figure heavily in Jemisin’s writing – not just in her novels, but in her short fiction as well. Her story Stone Hunger opens with a spectacular image of a city “winching its roof into place against the falling chill of night” to escape an apocalypse.

Fortunately, she’s a lot more positive about where cities are going in real life. “I’m a city kid,” she says. “We’ve been, for quite some time, a primarily urban species. I think there’s a certain amount of romanticising of life in the country, but in the US, we’ve been urban for decades now. I think the world is moving in that direction. Yeah, there will be problems in that we don’t have the technology yet or the planetary will to make our cities efficient and environmentally friendly. We need to move further in that direction technologically, and we aren’t taking the steps that are necessary to go there. I see some countries beginning to make those steps, and they could drive the phenomenon. But we’re in a capitalistic system that fights that, and there’s too much money to be made from things like fossil fuels.”

She does however think that those problems have a solution, even if we haven’t hit on it yet. “Look at the Tesla corporation, who are doing interesting things with electric cars. They’re thriving. They’re doing really well, despite predictions that they’d be doing poorly. And there are actually towns and cities in the United States that are trying to outlaw Tesla cars. There are senators and politicians trying to put legislation into place to prevent them being developed further. [But] I think it’s entirely possible that an independent inventor or entrepreneur can make these things work.”

– John Scalzi’s –

Everlasting Youth

Few writers are as entertaining as John Scalzi, or have as much to say. His personal blog gets tens of thousands of unique hits every month, and to become one of his 77,000-odd Twitter followers is to become the recipient of an endless stream of consciousness on everything from technology to publishing to classic movies. He made his name as a science-fiction writer, specialising in military sci-fi and high-concept ideas. When it comes to what the future is going to look like, Scalzi may not have exact predictions (“Because science fiction writers have such a sterling record of accurately predicting the future!”), but he certainly has an opinion.

New bodies

Scalzi’s Old Man’s War series deals with the idea of transplanting consciousness into new bodies. In it, a geriatric writer has his mind transferred to a battle-ready body so he can fight in an alien war. It’s an idea that Scalzi loves exploring – in his most recent book, Lock In, humanity is hit by a paralysing virus that forces victims to interact with the world through synthetic avatars. Everlasting youth has been a preoccupation with humans for a very long time, but Scalzi says that he’s not sure that we’ll have the technology to body-hop any time soon.

“I believe that in the next fifty years or so, we will crack some of the physical issues surrounding longevity,” he says. “We’re not going to have immortality – sooner or later, proton decay will get us all – but the idea of being able to double the lifespan, or triple it, is not completely unreasonable to me. The problem with that is that so much of our culture and society is predicated on people having a lifespan of roughly seventy years. Are we ready for another fifty to seventy years of Madonna? Or Bruce Springsteen? Or Charli XCX? Culture will get cluttered with all these people who just won’t go away!”

He also says that the population explosion that comes with this life extension will cause huge problems. “What you do when you have all these people who would normally die who aren’t dying? Would that be reflected by fewer and fewer people giving birth? Would that be reflected by the population becoming massive before the death rate catches up? We’d have to deal with all of this.”

Other planets

“I’m a geek,” says Scalzi, “and I want to go to Mars or Venus or the moons of Jupiter because that would be cool.”

But while we’ve certainly got the technology to make interplanetary trips, we would have to have sufficient motivation to do so – beyond it just being cool. It’s far more likely, Scalzi says, that humanity “deals with its climate issues and rides it out as best we can, while we keep the levels of extinction and death and pain and horror to strictly manageable levels.”

“The question becomes, what does this exploration give us that we don’t already have?” he adds. “You can say that, existentially, it gives us a foothold to another place in the universe if our world blows up. But have you seen Mars? It’s not exactly a welcoming place. It’s no place to raise your kids. It’s cold as hell. And the idea of, oh, we’ll terraform this? Well, unicorns might fly out of my butt, because the technology for massive and intentional terraforming, as opposed to the random terraforming that we’ve been doing here on earth, is substantial. At this point, there is no reason to go to another planet other than from the pure shits and giggles of it.”

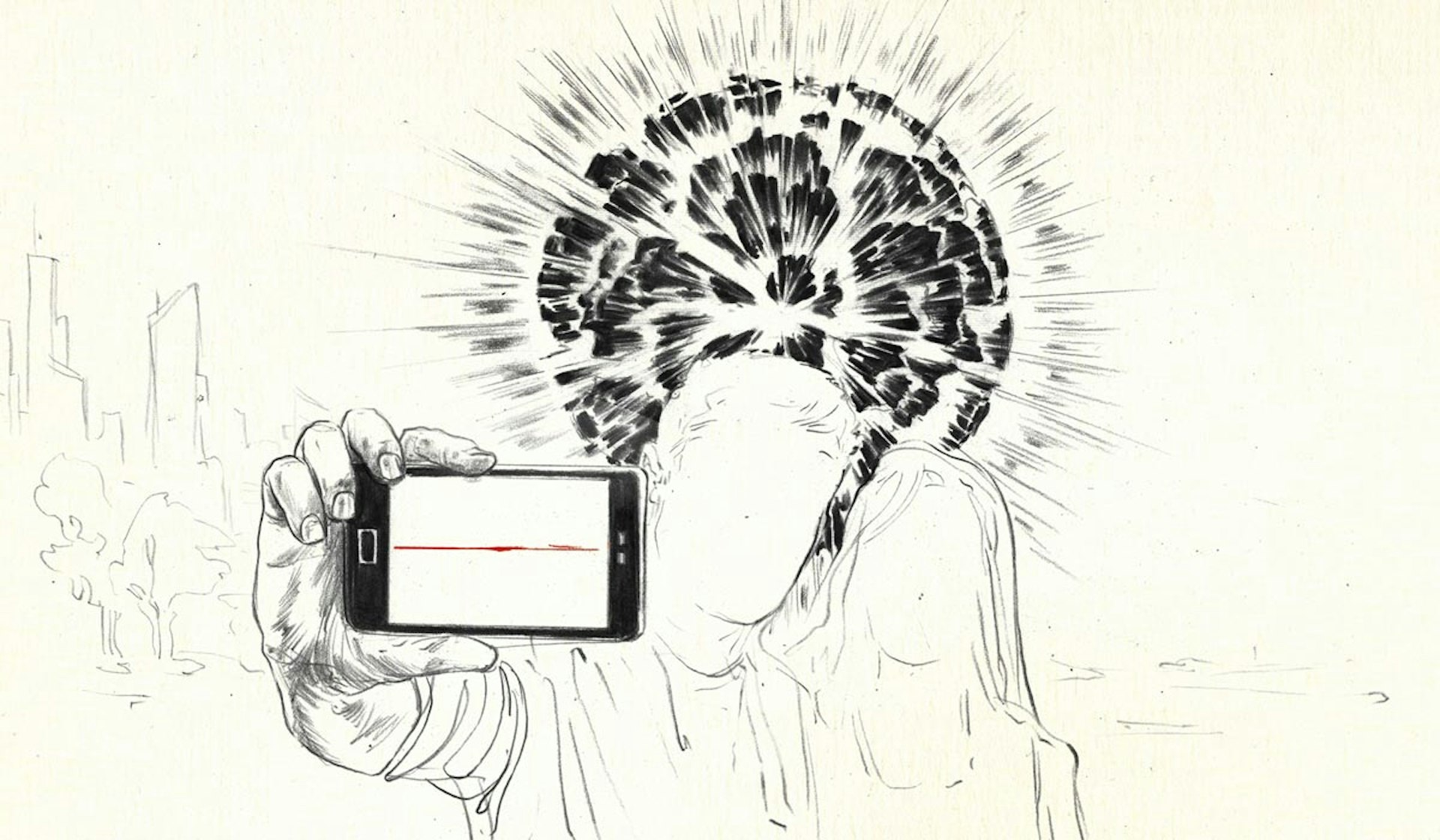

Social media

So new bodies are out. Holiday trips to Jupiter are most definitely out. But social media, in one form or another, is here to stay. Scalzi might doubt the accuracy of his own predictions, but you can probably trust that one.

It’s definitely not, he says, going to alter our brain chemistry, as naysayers have suggested. “I do agree that there are some aspects of social media that are going to have negative effects – the question is whether they’re going to be so profound that they’ll be like nothing that came before them. But I’m sceptical about that. The only thing I think is true is that the rate of technological change and the rate of acceleration in epochal new media does sometimes feel like it’s accelerating.”

He adds: ”My expectation is that social media will do very little for how brains actually work, and in ten or fifteen years, there’ll be some new iteration: either social media or some form of entertainment media. It’ll be new, it’ll be exciting, the teenagers will get to it first, they’ll understand it, everyone else will be in a moral panic because anything that teenagers do is wrong. And ten or fifteen years after that, the same thing will happen and the cycle will begin anew.”