This is what 30 years of British counterculture looks like

- Text by Khadija Ahmed

- Photography by Matthew Smith

Matthew Smith can pinpoint the moment he decided to become a photographer.

He was sitting in a workshop on politics and communications when a guest lecturer produced some raw footage of the Stonehenge festival in 1985.

The screen flashed with images of police smashing in bus windows, pulling people through the broken glass, abusing and threatening the festival-goers – even pregnant women and children.

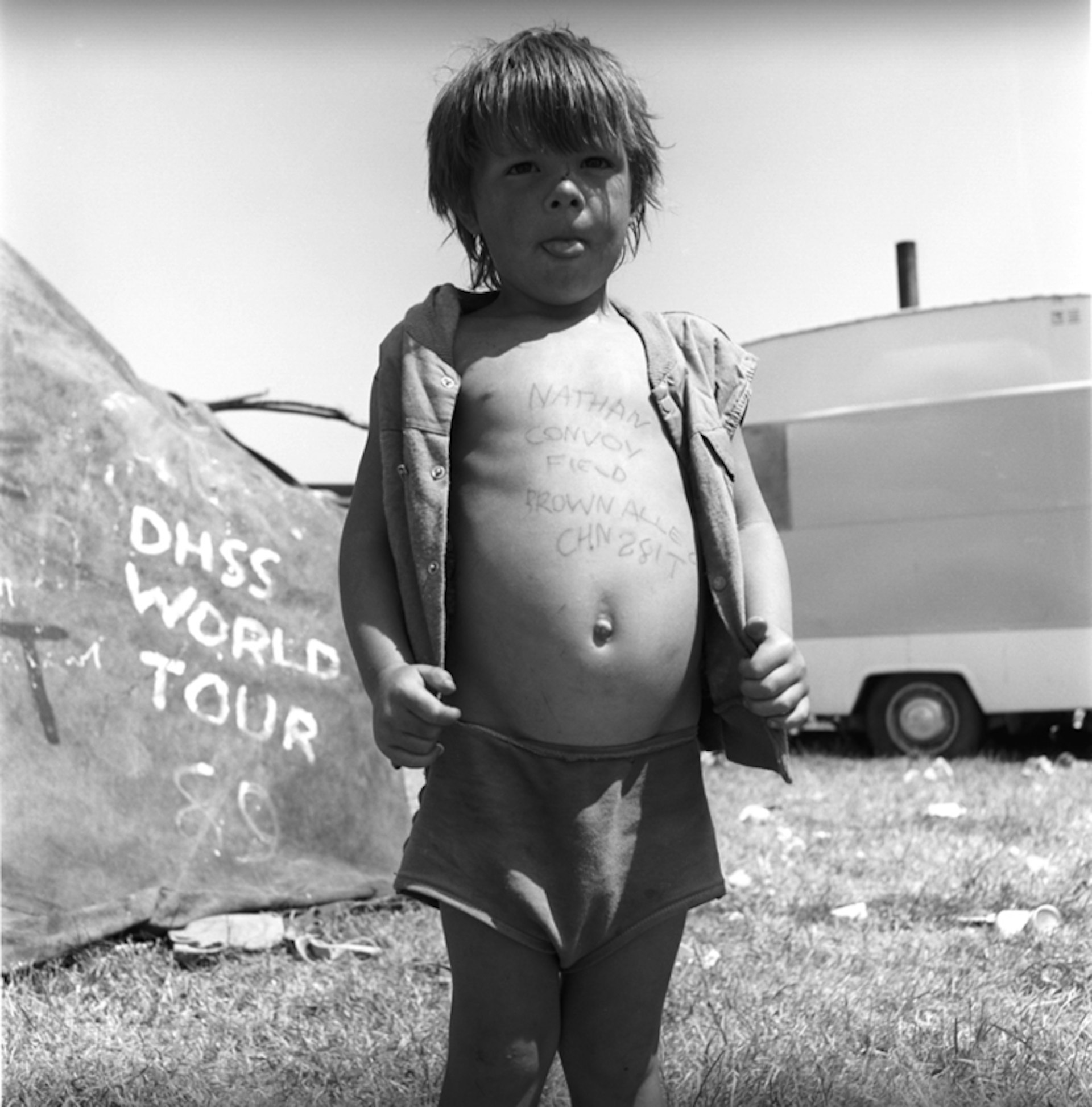

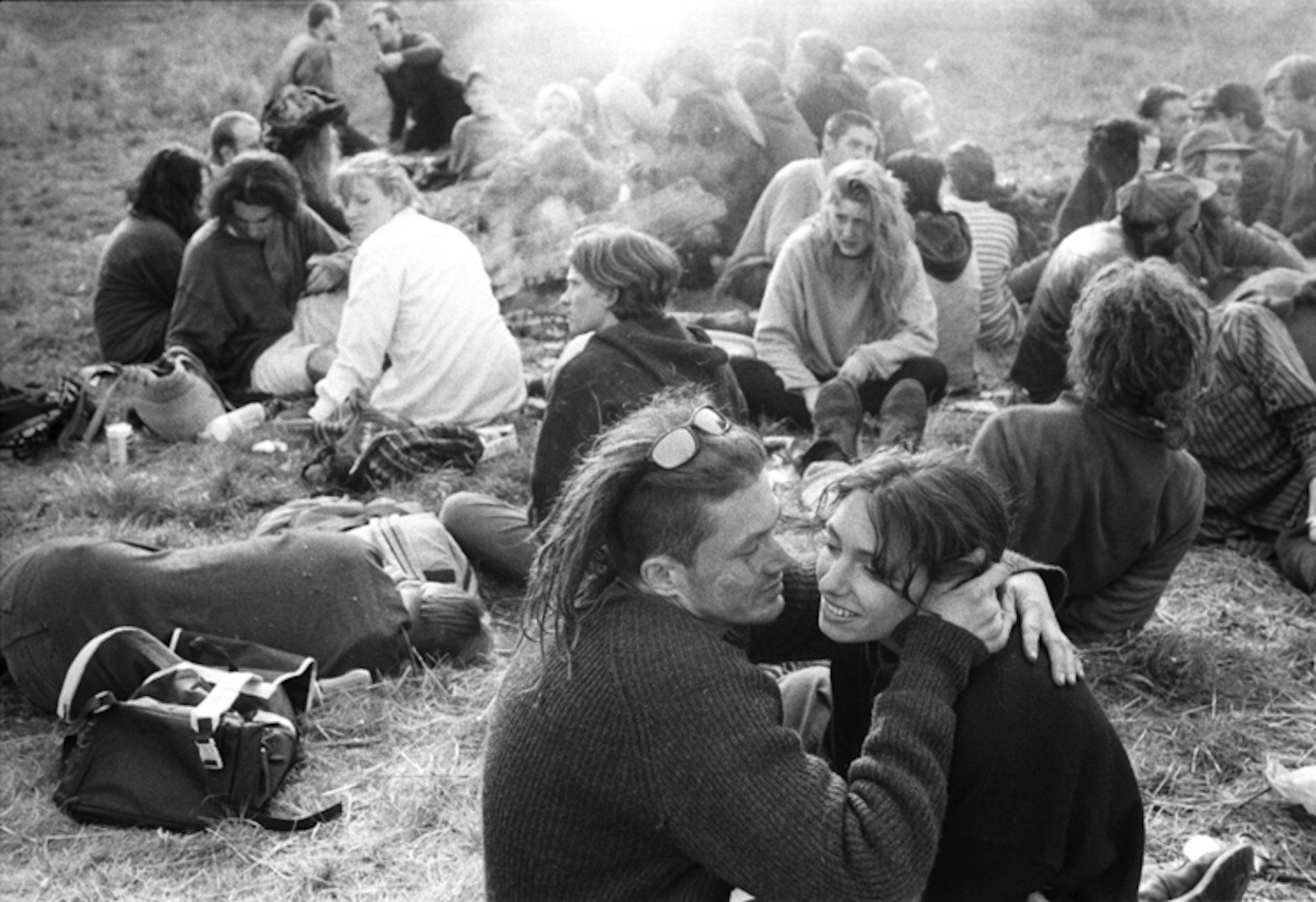

At the Mother Free Festival at Bridgwater Bay, 1995.

At the Fairmile, Trollheim and Allercombe protest camps in Devon, 1996.

Then the guest speaker, a news editor from HTV, showed the edited footage: a three-minute clip condensed for public broadcast. The violence had been removed. There were no tears. Law and order had been restored.

It was, Matthew says, “clearly a lie made from a truth” – and inspired him to think carefully about how he represented reality and how media represent the truth to the public.

In the 30 years since then, the photographer has been chronicling British counterculture on his own terms.

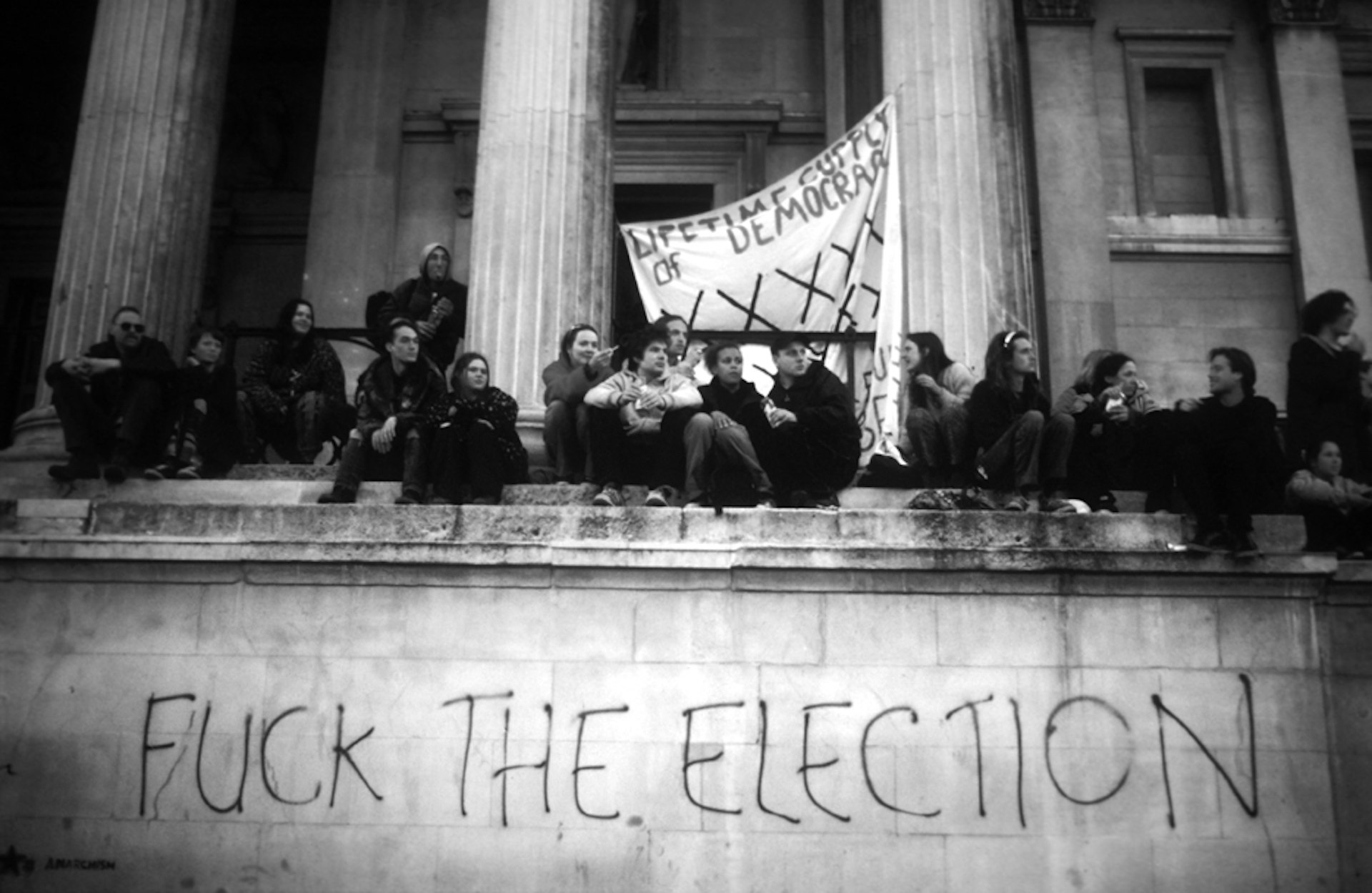

May Day Protests 1997.

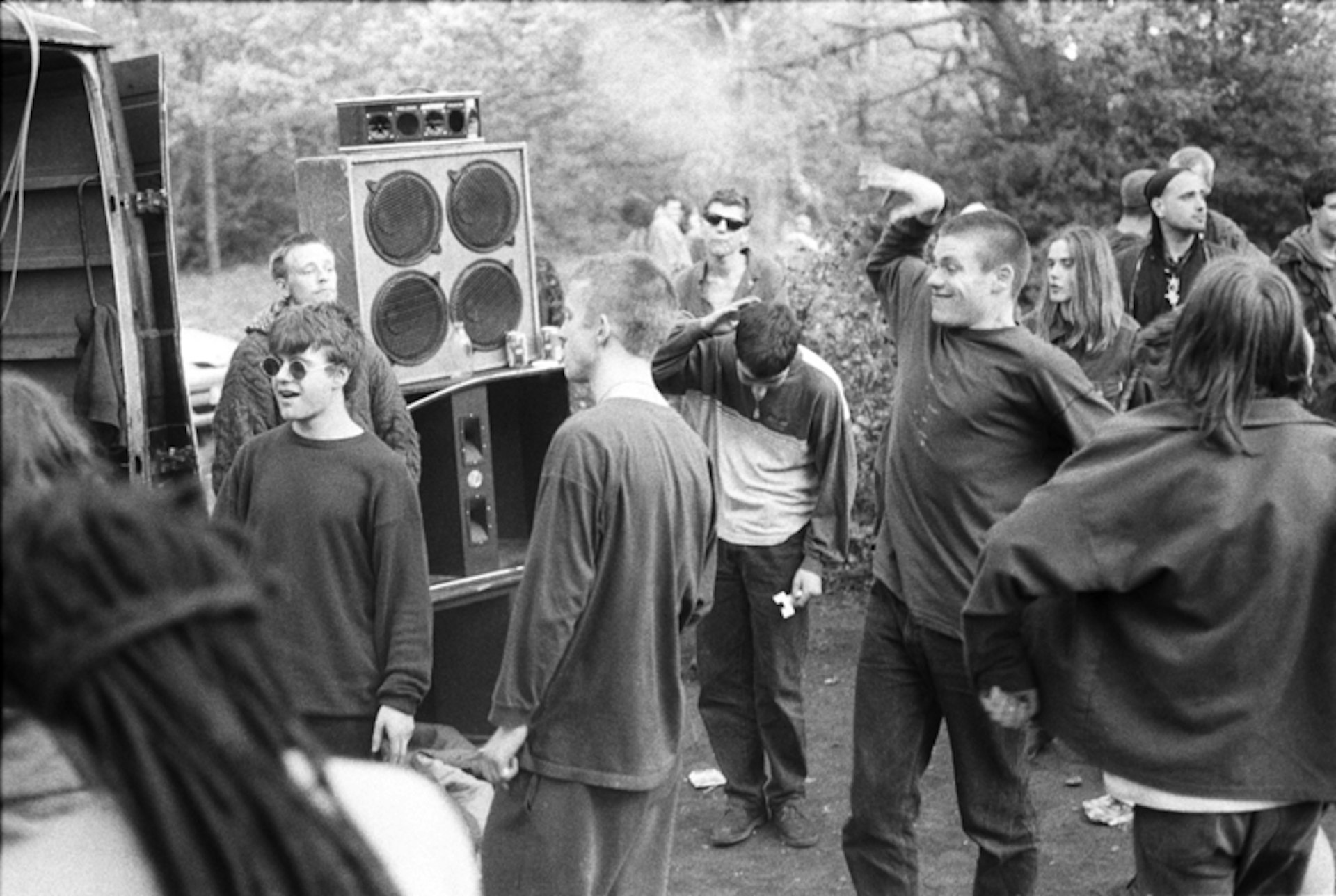

At the Mother Free Festival at Bridgwater Bay, 1995.

An afterparty in Wanstead, London, following the Anti-CJA march, 1994.

Having first set out with nothing more than a manual Nikkormatt camera and a 35mm lens, Matthew has continued to document the times he’s lived through and the people and he’s lived through them with.

What drew you to raves, protests and festivals?

The first protest I ever went to was the poll tax demonstration which turned into a riot [in 1990]. I went to college just down the road from Manchester in the late ’80s; I’d been to Glastonbury and we were going to [infamous nightclub] the Hacienda – but it was the free parties that were really exciting. That whole culture and atmosphere felt incredible to be a part of.

After I’d left art college, the prospect of this culture being criminalised through legislation started to become a reality.

It was in this light that we decided to act out our personal political convictions by trying to perpetuate and document that culture any way we could.

Bite marks from a police dog.

You were part of the G20 summit protests in London in 2009 where Ian Tomlinson was killed after being struck by a police officer. What was that experience like?

Most probably the scariest situation I’ve ever been in – and I’ve been in quite a few riot situations.

I got kettled [a police tactic for controlling large crowds] for four hours in two different locations. [It was] incredibly passive aggressive: being contained without arrest and having every single human right taken away from you for no other reason other than you are present in a crowd. That’s a very scary thing.

Glastonbury 1989.

What has changed over the last three decades, from your point of view, in terms of protests and festivals?

When I began taking photographs, there were only maybe five [outdoor cultural] events that were legal. At that time it was much more about individuals bringing as much as they could to festivals. People used to be able trade things among themselves.

Now, post-legislation, everything has to be registered and programmed. There’s a massive industry around it where there are 500 events in England alone.

The Home Office even dictate that we have to prove our identities by showing passports in order to work at Glastonbury, for instance. That never used to happen! In an era of big data, that is suspicious.

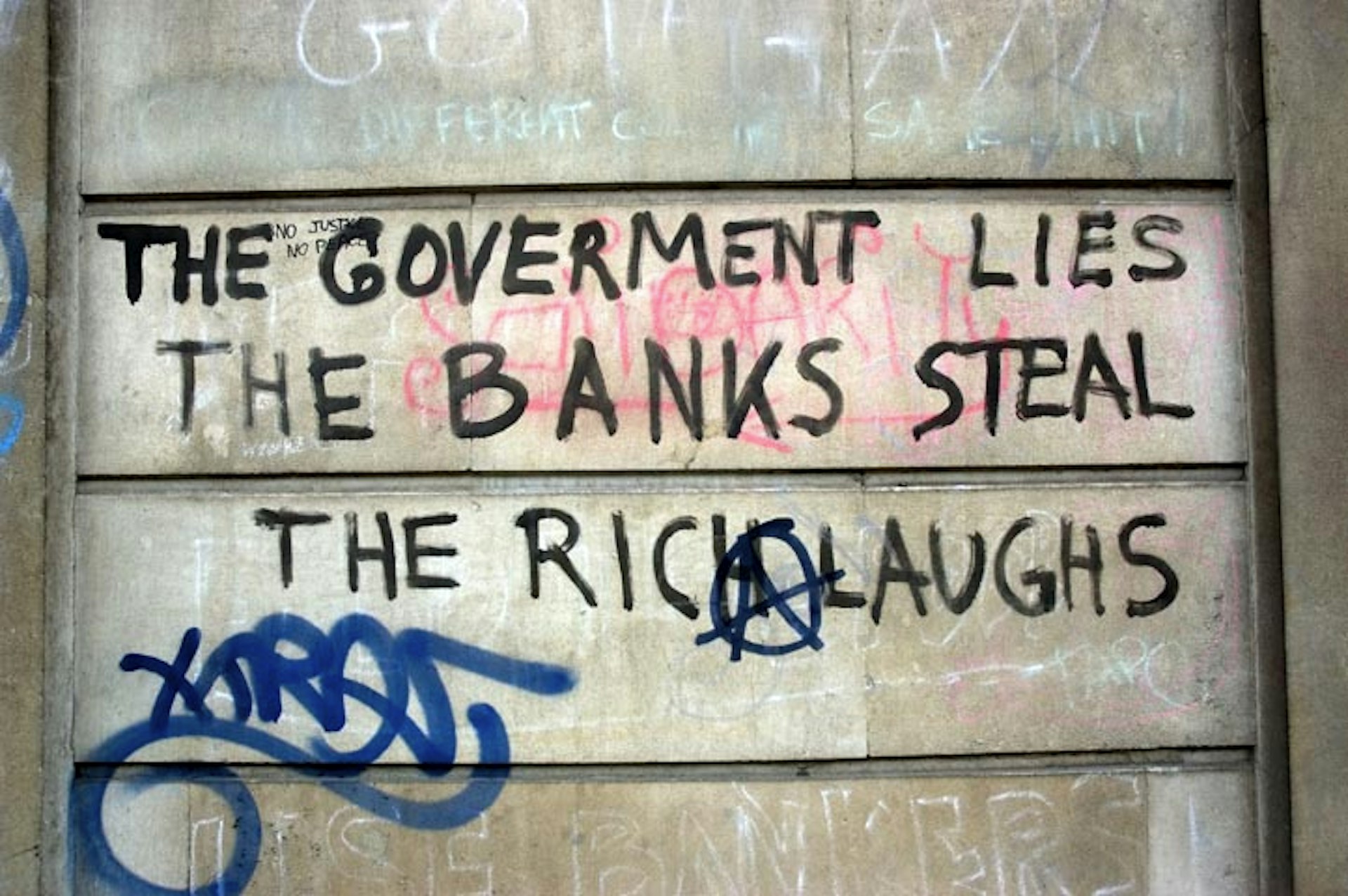

May Day Protests, London 2010.

At the Mother Free Festival at Bridgwater Bay, 1995.

At the Fairmile, Trollheim and Allercombe protest camps in Devon, 1996.

Was there a point where people became wary of photographers?

In the early days people were always wary of photographers. Photography now is being democratised by digital and mobile phones, which was undreamt of when I was studying photography.

Now everybody has a camera and the ability to transmit that information immediately, which is a massive difference because there’s no going back to the dark room anymore. You can be in the middle of a trouble hotspot and be sending continuous pictures to your friends as it’s happening.

Another thing that has changed is how the State deals with the public in certain situations, like sending in riot police, because there are so many cameras now. Police can’t be seen beating the shit out of everybody; there are too many witnesses.

At the Mother Free Festival at Bridgwater Bay, 1995.

Protest against the Criminal Justice Act in London, July 1994.

Mosside Carnival, Manchester 1989.

What has been the greatest difficulty or challenge so far for you as a photographer?

Surviving. Surviving in a world where everyone wants to take our copyright, where everyone wants your work for free, where equipment has become prohibitively expensive and something you have to update to keep up with the competition.

What image or achievement are you most proud of?

I think that the whole process of spending the last four years scanning all the film that I shot has been a very interesting journey. You get to re-examine pictures that you never thought were worthy in the past.

There are several hero kind of images, like the one of the guy at the riot in Park Lane, standing in front of the line. I will remember that moment forever.

One man stands between the headlights of two riot vans at the third Anti-Criminal Justice Bill, London 1994.

Middlesex University, October ’94.

These riot police were repeatedly charging the public behind us pinned behind the iron railings of Hyde Park.

I stood behind the man in the image as he exhorted the police calmly, assertively and repeatedly to stop their violence.

That, for me, stands out as a moment that I really identify with: somebody who was being completely reasonable in the face of aggressive force.

At the Mother Free Festival at Bridgwater Bay, 1995.

An afterparty in Wanstead, London, following the Anti-CJA march, 1994.

Matthew Smith is about to launch a Kickstarter campaign to self-publish a modern history book comprised of his documentary photography. For more information, visit his website, follow him on Facebook or check him out on Instagram.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.