An insider look at Kurdistan’s fight against ISIS

- Text by Eva Clifford

- Photography by Joey L.

“I could read all the articles, books, and social media accounts in the world about what led to the war in Iraq and Syria, but that doesn’t constitute experience,” writes photographer Joey L. in his book We Came From Fire: Photographs of Kurdistan’s Armed Struggle Against ISIS. “The reality was that a burning curiosity – or shall I say a compulsion – drove me to observe what was happening on the ground with my own eyes, independently and unfiltered by the media I had lost trust in.”

Joey’s true learning experience began with his first day on the ground, in March 2015. On a self-funded trip to the Kurdistan region of Iraq and Syria, he embedded with Kurdish guerrilla groups fighting against ISIS. A lot would change over the following three visits, but Joey’s motivation remained resolute: to capture the human side of a fast-evolving conflict.

“I’ve always had an interest in distinct cultures and endangered language groups,” Joey tells Huck. In Indonesia and Ethiopia, he photographed indigenous populations who had found themselves restricted within the borders of a nation state they had little to no say in creating.

“Consequently, they have been historically oppressed by an invading force, authoritative regimes, or another ethnic group. And so, witnessing Kurdish resilience prevail before me in their fight against ISIS provided me with inspiration, and a deep appreciation for their struggle.”

Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) guerrillas on an armed patrol in the countryside of Makhmur. Makhmur, Erbil Governorate, Iraq, March 3, 2015

“In a corner of the world that you wouldn’t expect, the Kurdish population began its own renaissance in a way,” he says. “When the Syrian state retreated from predominantly Kurdish areas, civilians in the region armed themselves against jihadist groups hellbent on genocide… The war became a backdrop to these fighters who were not only fighting ISIS, but preserving and reviving their suppressed identity.”

Over the course of four separate trips – ranging from a fortnight to 40 days – Joey witnessed the region’s transformation, leading to a deeper, more nuanced understanding of its complexities.

“This project actually took so long to finish that the photographs would not even be considered relevant as photojournalism for a typical news cycle,” says Joey. “While that kind of media is important, the way in which the information is provided to their audience is rapid, and can oftentimes provide a superficial account of the conflict.”

“When I decided to pursue this mission as a personal project, I knew I had no constraints.”

Back home in Brooklyn, New York, the Canadian-born photographer is used to shooting high profile portraits, and his ability to connect and make people feel at ease visibly translates to his work in Iraq and Syria. He captures the camaraderie of the fighters; the laughter and everyday interactions that aren’t shown in typical news coverage.

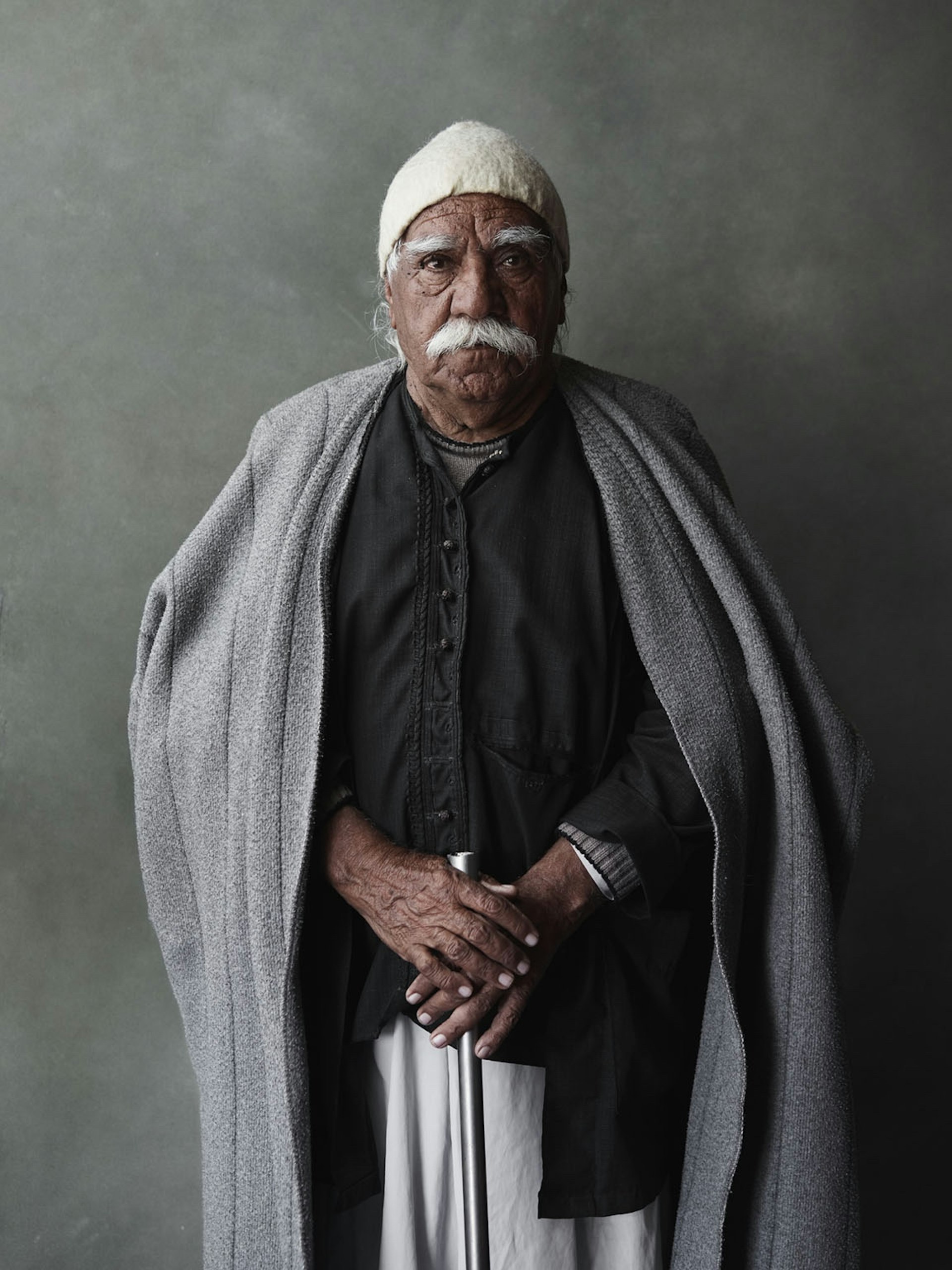

Assembling a makeshift portrait studio at a Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) base camp, Joey captured individual portraits against a smokey, hand-painted backdrop: “The goal for these portraits was to remove the sense of place and allow the viewer to focus on the details of the fighters themselves.”

Cudi Serhed, commander of frontline operations in Shengal for People’s Defense Forces (HPG), the armed wing of the PKK. Shengal, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, November 22, 2015

Eyes fixed directly into the lens, they each hold stories we will likely never know. In the book, Joey calls our attention to a portrait of a young female fighter with the nom de guerre ‘Sarya’: “Her hands, grasping an RPG [rocket-propelled grenade], were marked with the signs of a hard-fought war: burns and scars. She appeared in the frame as diminutive and formidable at the same time – her expression stern, yet effortless.”

Throughout the trip, Joey was aided by local Kurdish fixer, journalist and translator Jan and his wife Ipek, whose assistance proved invaluable. “Without Jan, I wouldn’t have got any of these photos,” he admits.

“Any photographer embedded with the Kurds find him or herself well-protected, and I am thankful for that. But needless to say, there were some risky situations beyond anyone’s control. The worst is when you feel helpless, when no amount of preparation or bravery will help you.”

He recalls how one time during the military offensive to surround the ISIS-held city of Raqqa, he was embedded with a mixed Kurdish and Arab unit of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), when their position was shelled by ISIS.

“Mortars were hitting 20-50 metres away from us in the open ground and we were laying down, just waiting for it to end,” remembers Joey. “The sound of mortars falling from the sky almost sounded cartoonish, and unreal… It was truly terrifying. And this experience of mine alone, was only a small snippet of the day-to-day life of these fighters.”

A large memorial statue dedicated to the martyred female fighters of Rojava overlooks a city roundabout. Kobanê, Kobanê Canton, Rojava, Syria, November 13, 201

Asking how reality compared to mainstream news coverage, Joey says he believes that the Syrian conflict was depicted incorrectly for numerous reasons.

“First and foremost, it’s nearly impossible to present the complexities of such a conflict in the format that works with modern corporate media. Presenting complex conflict analysis in a matter that simplifies it to a broader audience can be detrimental. This formatting leaves out essential elements that really, contribute to the larger narrative at hand.”

“The biggest surprise for me was the role that outside nations played into backing various rebel groups, especially with the nation of Turkey. I strongly believe Turkey has backed jihadist groups against the Kurds since the beginning of the war. You begin to feel that there is a larger international conflict being played out using the blood of local people.”

We Came From Fire takes its name from an ancient Kurdish proverb kept alive by oral tradition: we came from fire, and we will return to fire. Joey says that primarily, this project is “a cultural study of Kurdish people” – a people who have faced centuries of persecution and continue to struggle for their independence.

“My goal was to create something intimate and humanising. To which I think was depicted through the individual stories of each fighter I encountered. Each subject had a lot to contribute.”

Portrait of Sarya with rocket-propelled grenade launcher.

Makhmur, Erbil Governorate, Iraq, March 4, 2015

A family watches from their rooftop as firefighters struggle to extinguish a wall of flames creeping closer to their home. Qayyarah, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, October 26, 2016

PKK guerrillas pose near their trench position outside Makhmur Refugee Camp. Makhmur, Erbil Governorate, Iraq, March 4, 2015

Silava and Berivan share a laugh in an abandoned ISIS base. Shengal, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, November 23, 2015

Portrait of survivors of a Êzidî genocide: Sehdo Xelef. Newroz Refugee Camp, Derîk, Jazira Canton, Rojava, Syria, March 13, 2015

Perwîn, a volunteer YJÊ fighter, inside an abandoned Christian church. Shengal, Nineveh Governorate, Iraq, November 11, 2016

We Came From Fire: Photographs of Kurdistan’s Armed Struggle Against ISIS is published by powerHouse Books.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.