What it's like to stay with strangers around the world

- Text by Bieke Depoorter

- Photography by Bieke Depoorter / Magnum Photos

I grew up in quite a small, conservative town in Belgium where I had no real familiarity with art. I don’t think I even visited a museum before the age of 18.

That world seemed like it was meant for other people. But the summer after school, I decided to take an entrance exam to study photography in Ghent – only telling my mother and sister.

I felt like I had to give it a try, otherwise I’d end up doing something I didn’t want. But from the moment I stepped into the school, I knew it was for me. The idea of photography being my day-to-day life, surrounded by like-minded people, just felt right.

My first big project Ou Menya, formed out of an idea to travel along the Trans-Siberian Railway. I was 21 and didn’t have any money to pay for hotels – the little villages I wanted to visit didn’t even have hotels – so I carried a note in Russian asking people if I could stay at their place.

For me, it was just a strategy to avoid sleeping on the streets. But immediately I felt comfortable in a way that I never could as a street photographer. People act differently when they’re at home at night.

Within a matter of hours, we would build an affinity – even without speaking the same language – where I could be in the sauna photographing them naked. I decided I would do this every night, letting that note lead me on a completely different project.

Two years later, in 2010, I wanted to apply the same approach in a place where I could speak the language: America. Before, the lack of small talk left lots of room to observe.

In the US, people were eager to share their stories – maybe because they knew I was leaving the next day and we’d never see each other again – which impacted how the photos came about.

I spent a lot of time travelling from town to town thinking about the process. I kind of like the loneliness – I need it to be able to create work – but only because I have a good base to come home to.

People often ask me about staying out of danger. For me, it’s quite easy to see if you can trust someone. In the States, I stayed with people who would be considered criminals, but I think if you build a relationship, even with people who do things that are wrong, there’s a shared trust there.

It allows photography to become a conversation. This became a big theme in my next project, As It May Be, in Egypt. I was there for an assignment and saw how difficult it is to photograph in people’s homes; they’d get so protective about what was behind the door that I became fascinated, wanting to find trust in a place where there is not a lot of trust. I really didn’t want to do the same style of project again but, because it seemed impossible, I felt compelled to try.

During the daytime, a translator and I would walk through the streets, guided by intuition, searching for someone to stay with. It’s like a chain reaction where one left turn, one conversation can make all the difference.

Once we found a place, the translator would leave and I would stay by myself. But towards the end it became almost impossible. People would think I was a spy and call the police.

I started thinking about how to deal with photographing ‘the other’. I would never take someone’s picture if they didn’t want me to, so I kept asking questions of myself. ‘What am I doing here? Why do I want these pictures? What does it mean for them?’

I was making a project in a complex country that didn’t like photographs, yet that complexity wasn’t reflected in the work.

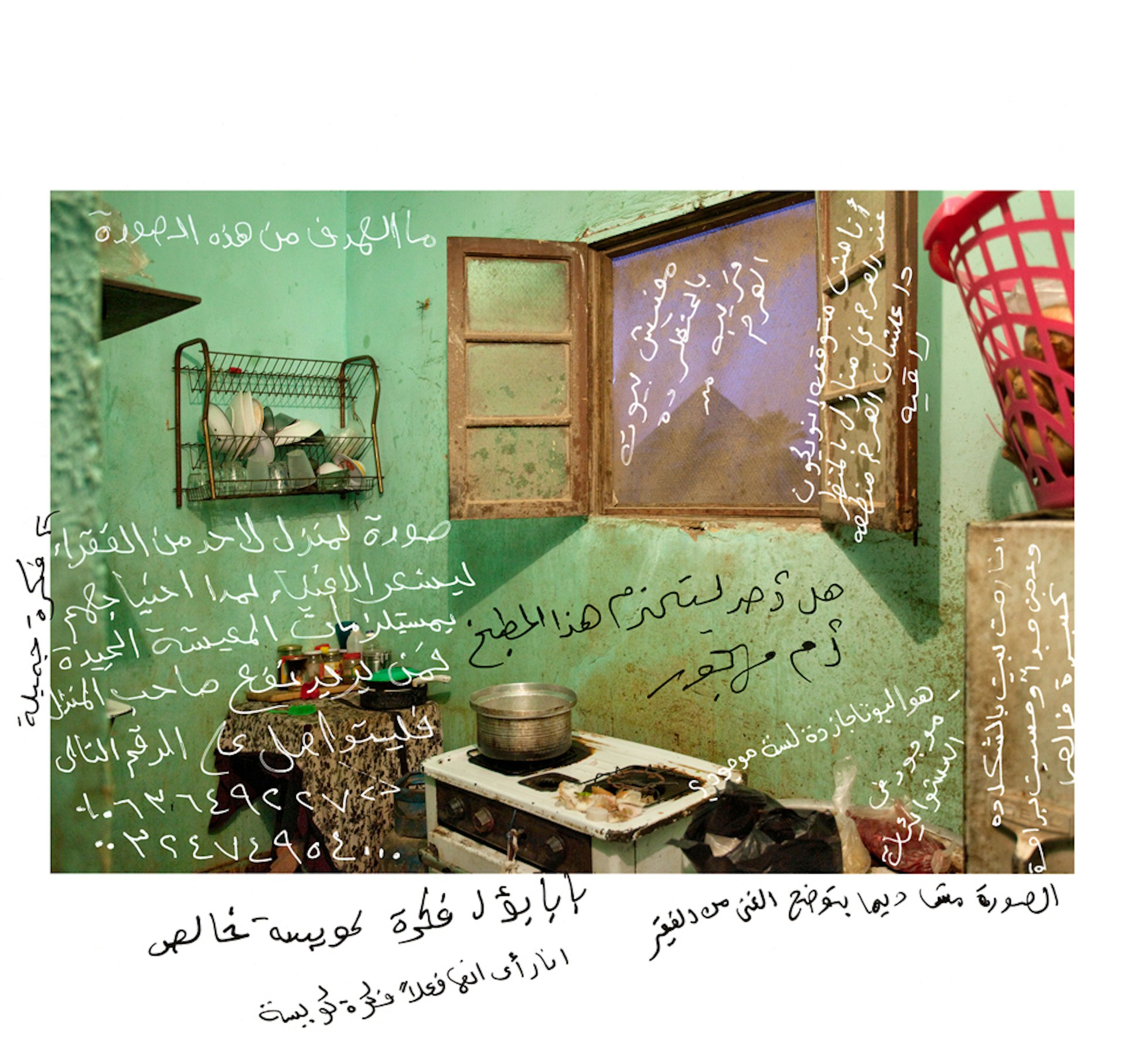

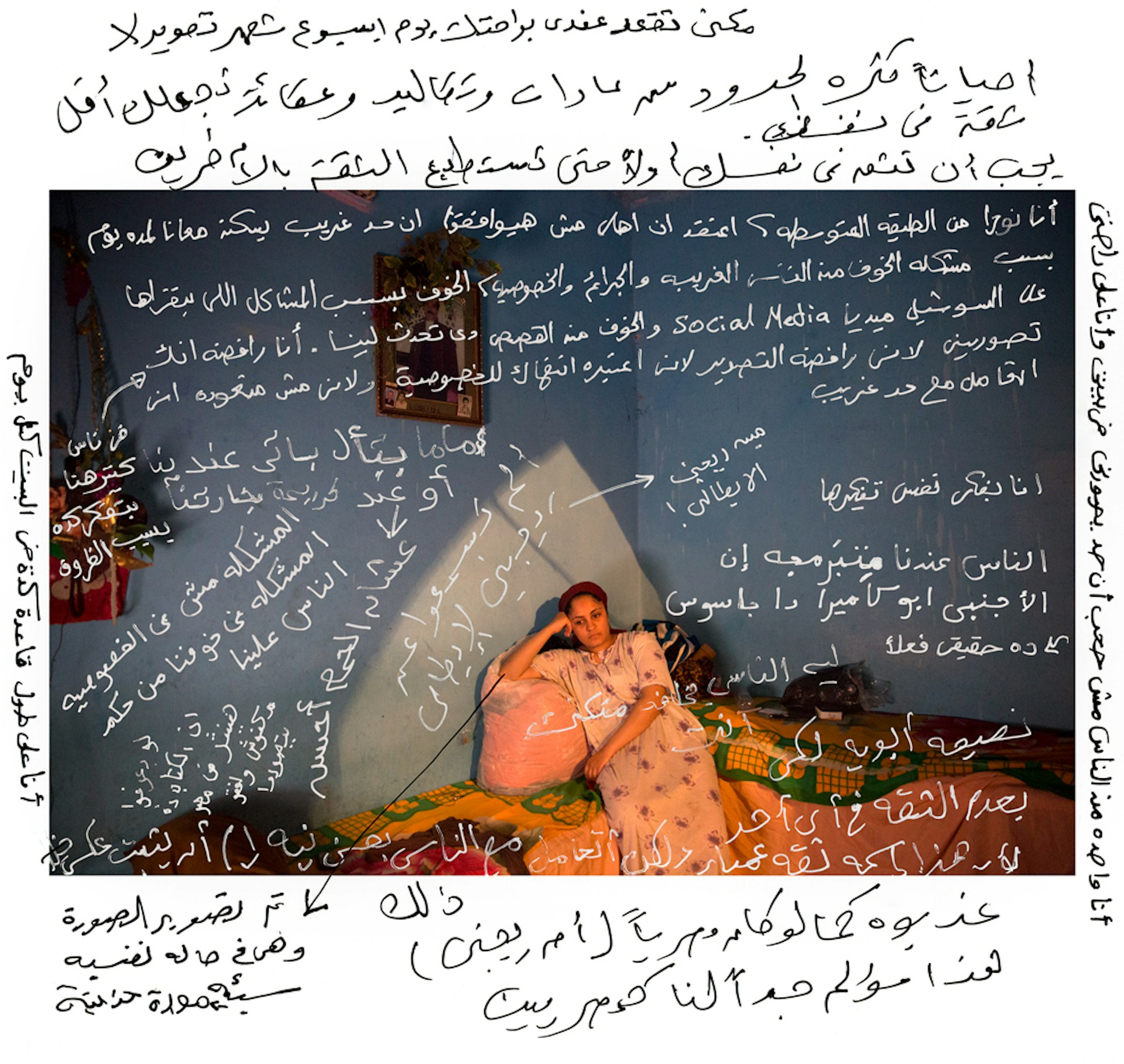

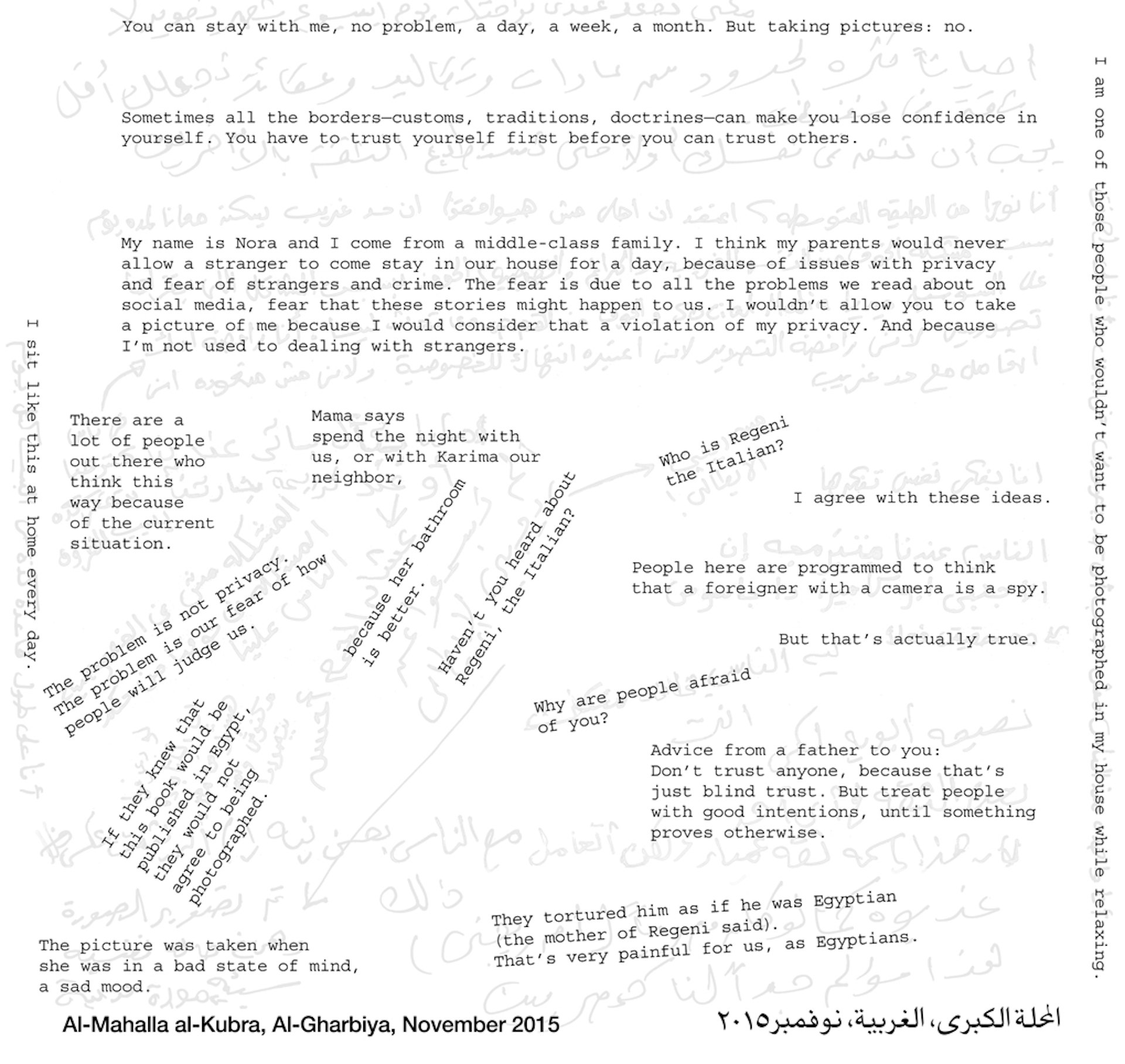

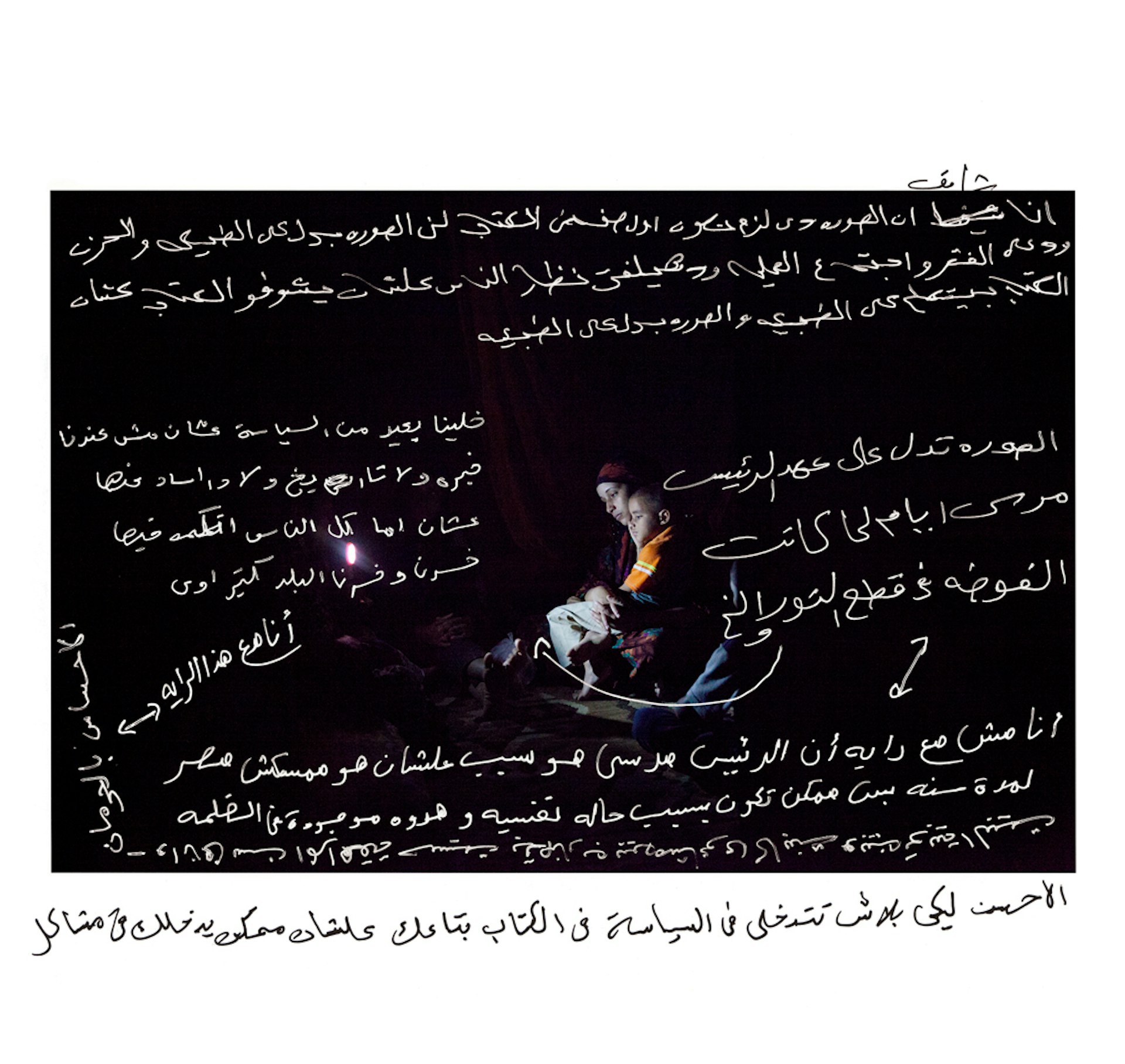

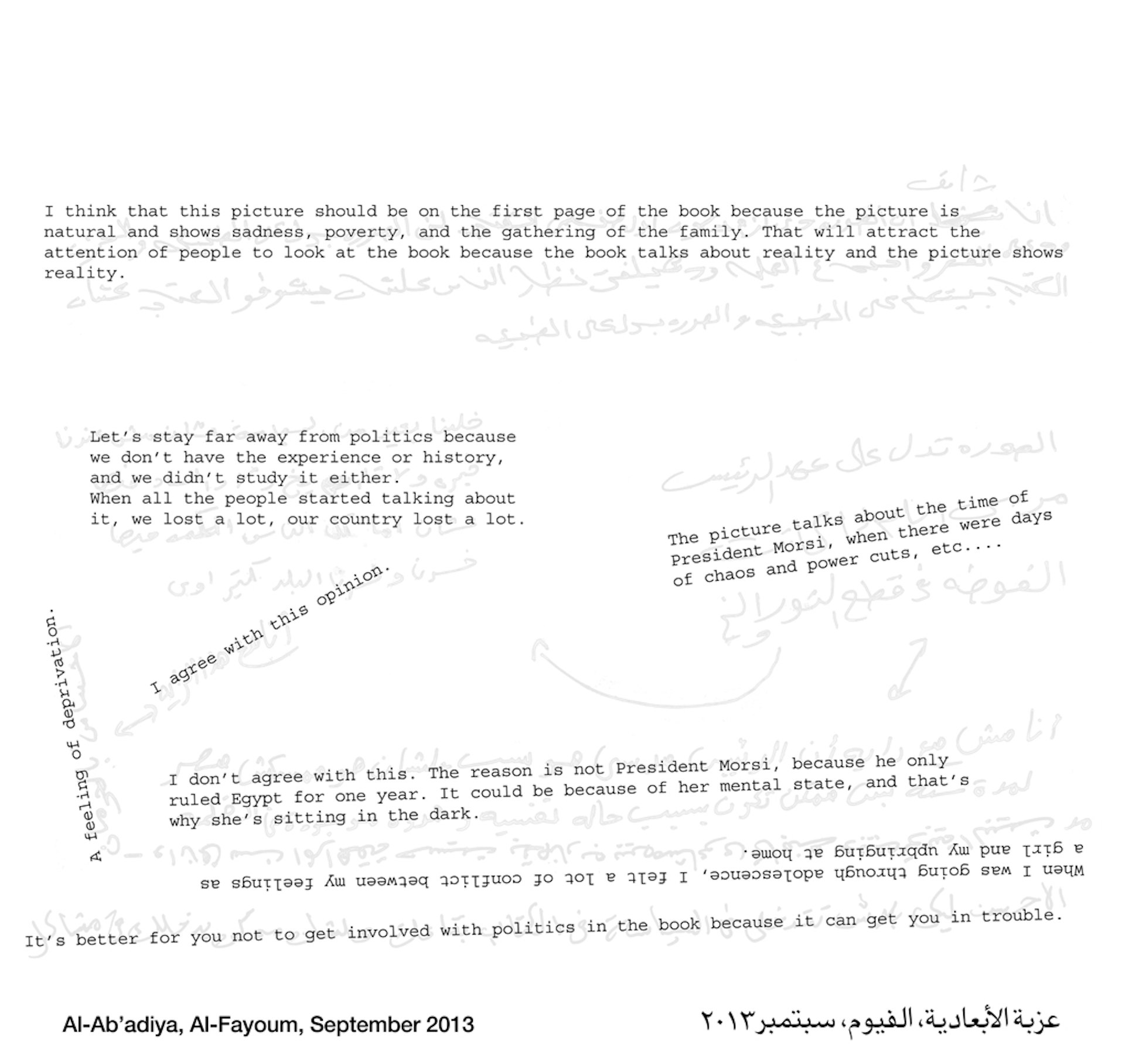

I made a book using images of people I had a good relationship with, but I didn’t want to publish it. It felt like I was presenting a Western point of view on a culture that was impossible to photograph. So I went back to Egypt with a dummy version of the book and asked people to write their reactions on the images.

I thought they’d tear the book up or get angry but, because I asked for their opinion, they were happy to address topics I had doubts all kinds of topics. This felt like a breakthrough: contrasting views on country, religion, society and photography could arise between people who would otherwise never cross paths.

I’ve realised that as a photographer it’s impossible to talk about the truth. The more work you make, the less innocence there is.

Sometimes you can start to see people as an object even if you don’t want to and, for me, that’s a big problem. I want to talk to people, to create relationships, to have a meaningful exchange.

Every time I start a new project, I fall into the same trap of feeling like I don’t know what I’m doing or why. Then I find an entrance, and everything’s fine again. It’s all a process of questioning photography and seeking solutions – and for me, collaboration is often the best way to navigate that.

Bieke Depoorter / Magnum Photos

As It May Be is published by Aperture. Bieke Depoorter is currently exhibiting her work at FOMU, Antwerp until 10 February.

This article appears in Huck 67 – The Documentary Photography Special VI. Buy it in the Huck Shop or subscribe now to never miss another issue.