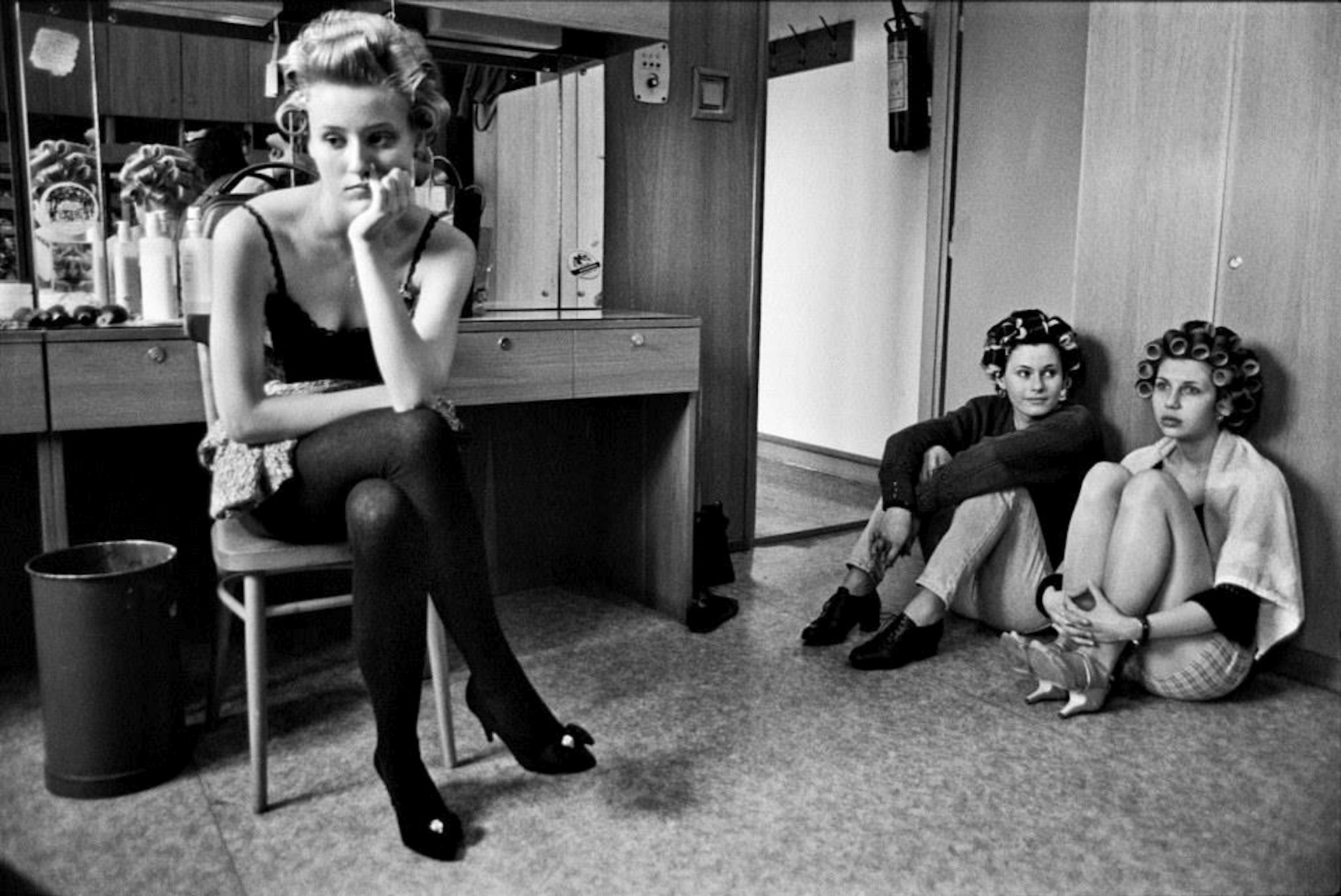

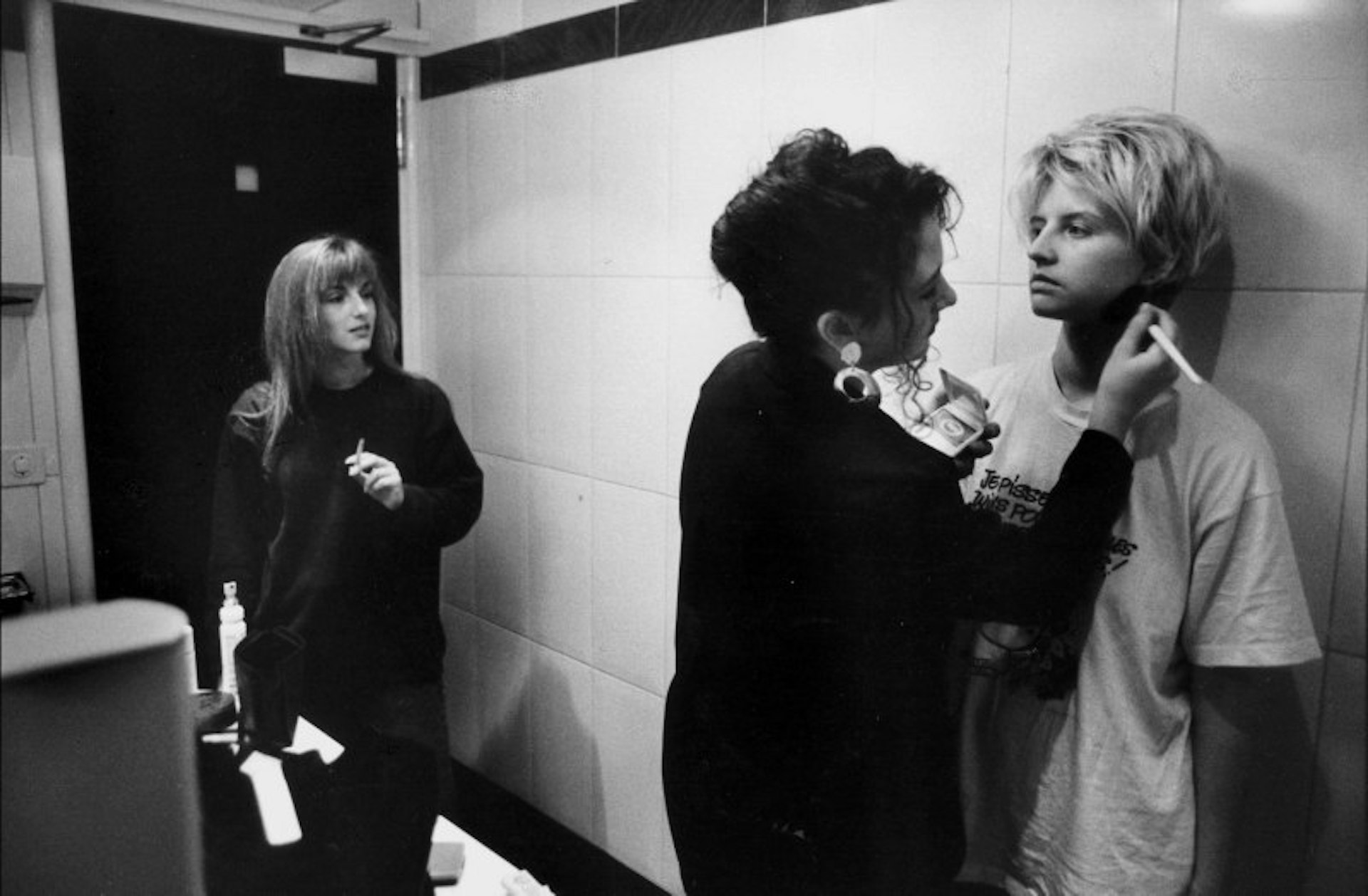

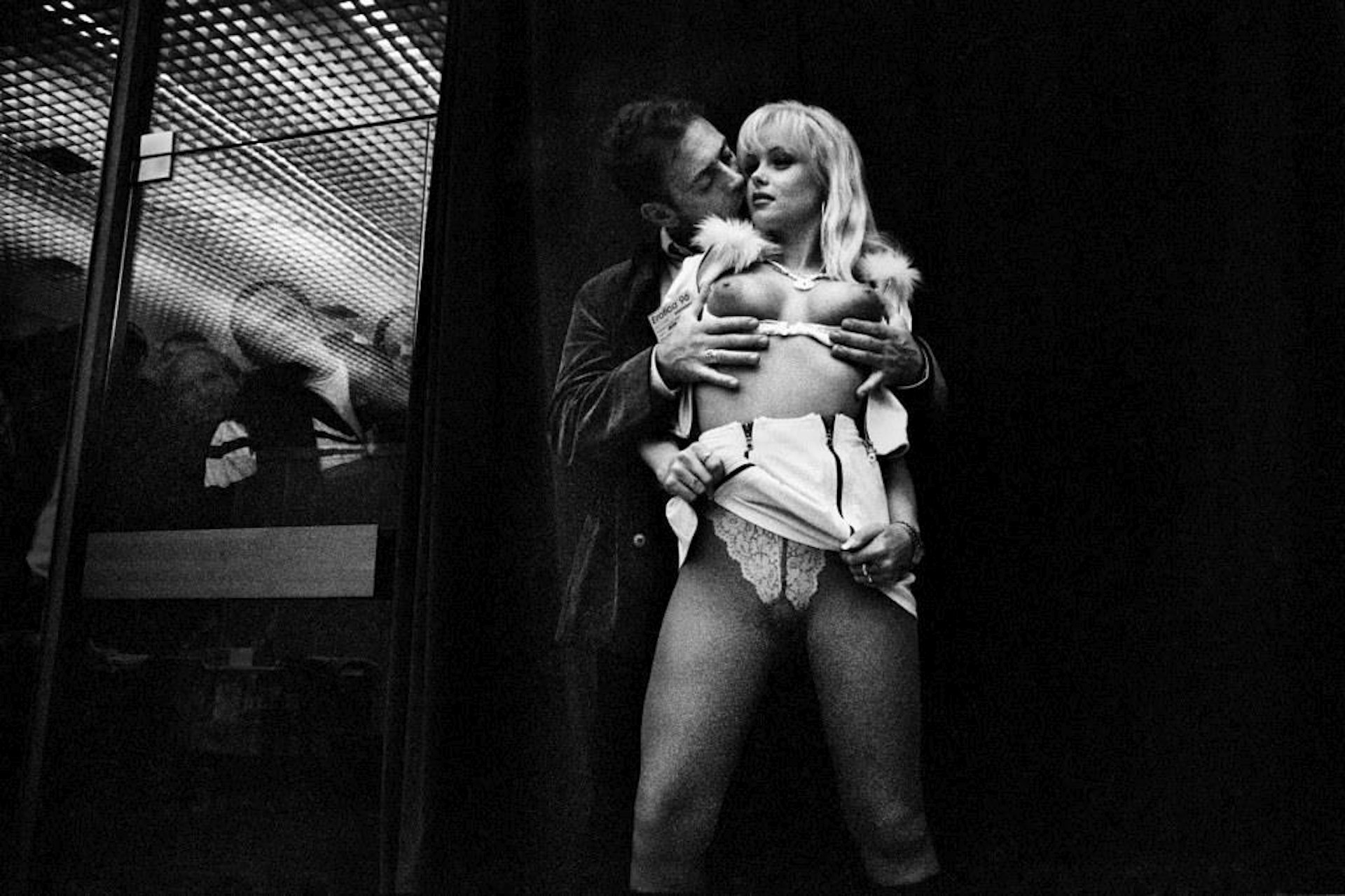

A portrait of womanhood in the Soviet Bloc

- Text by Cassidy George

- Photography by Dana Kyndrová

Women have been the subject of artwork since its first recorded existence. From the “Venus of Willendorf”, dating back to 24,000 BC, to Boticelli’s “The Birth of Venus” and Picasso’s “Les Demoiselles D’Avignon”, the female form has been an inspiration to famed artists throughout history.

Unfortunately, given that the majority of these artists have been men, much of these shifting renderings speak only to the surface level; to physical, rather than emotional womanhood. This deficit in experiential representation makes the work of female artists like Dana Kyndrová all the more substantive. The Czech artist has been photographing women for almost half a century, filling the gap between external and internal understandings of femininity.

Her lauded series Women Between Inhaling and Exhaling chronicles female life in former Czechoslovakia beginning in the 1970s, and after, during the uncertain transition from Communist rule to a post-Socialist nation. The sizeable collection is separated into seven pillars: adolescence, maternity, fun, work, eroticism, faith and old age. The moments between women’s first and last breaths – shown in photographs of Kyndrová’s own grandmother kissing her husband on his deathbed, a teenager in the passionate throes of a first kiss, and the agony and ecstasy of birth – are captured with intimacy and candour.

The push and pull between the individual and collective in the series is also a political one. Photographs of women in Western countries are sprinkled throughout the series, intentionally blurring the distinction between life on either side of the Iron Curtain. Her message – that the bonds of femininity and sisterhood transgress borders and ideologies – was a subversive one, particularly when the ruling ideology was rooted in maintaining divides. The divine, interconnected feminine she captures makes the role of place and political parties feel, in comparison, insignificant.

Though Westerners mistakenly envision the Soviet Bloc as a monoculture, Czechoslovakia had its own unique tale of resistance, attempted reform and eventually, peaceful overthrow during its 40 years under the thumb of the USSR. “I focused on the zeitgeist that arose after the Prague Spring,” says Kyndrová. “There was a certain amount of resignation within the atmosphere.”

Coming of age during a reactionary period between the Prague Spring and the Velvet Revolution made Kyndrová’s creative undertakings dangerous. The photographer played the role of an innocent young girl and amateur photographer to avoid suspicion from the Party and secret police, who did their best to limit artistic freedoms. “In the 1970s and 1980s, I was detained by the secret police multiple times,” she remembers. “Several times they opened my camera with exposed 35 mm film and damaged it. I was even interrogated.”

It comes as no surprise that the root of Kyndrová’s Women series and photographic practice is her own maternal connection. “My mother was one of my major influences in life,” says Kyndrová. It was her mother, a photographer herself and later an editor at a photography magazine, who introduced her to the work of Miloň Novotný: her key aesthetic influence.

“If the time was different, I would have studied journalism, but in the totalitarian regime, it would mean baring all of the connected risks.” By avoiding a career as a “professional”, she managed to document a reality that was her own, not one shaped by overarching powers. In the journalistic spirit, Kyndrová resolved to never stage her photographs, which blend a documentary style with cinematic drama. Today her images have an aura of timelessness, conveying scenes and situations that shape the female experience today, just as they did 50 years prior and likely, in the 50 years to come.

See more of Dana Kyndrová’s work on her official website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.