Dan Eldon and the power of creative activism

- Text by Eva Clifford

- Photography by © Dan Eldon / Courtesy of Dan Eldon Collection

On July 12, 1993, Kathy Eldon attempted to process the news that no mother ever wants to hear – that her 22-year-old son had been murdered.

Earlier that day, American-led UN forces had launched an aerial attack on the suspected headquarters of Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid in Mogadishu. More than 70 innocent civilians were killed.

In the ensuing chaos, a group of survivors drove to the hotel where Dan Eldon and fellow journalists were staying and urged them to come and capture what had happened. Promised protection, the journalists agreed. But while photographing amid the wreckage, a mob of enraged Somalis beat and stoned Dan and three colleagues, Hos Maina, Anthony Macharia and Hansi Krauss to death.

![]()

Dan was seven when he and his family relocated from London to Nairobi, Kenya. His journalist mother, Kathy, often took him and his younger sister Amy along on assignments, and it wasn’t long before Dan started shooting his own photographs.

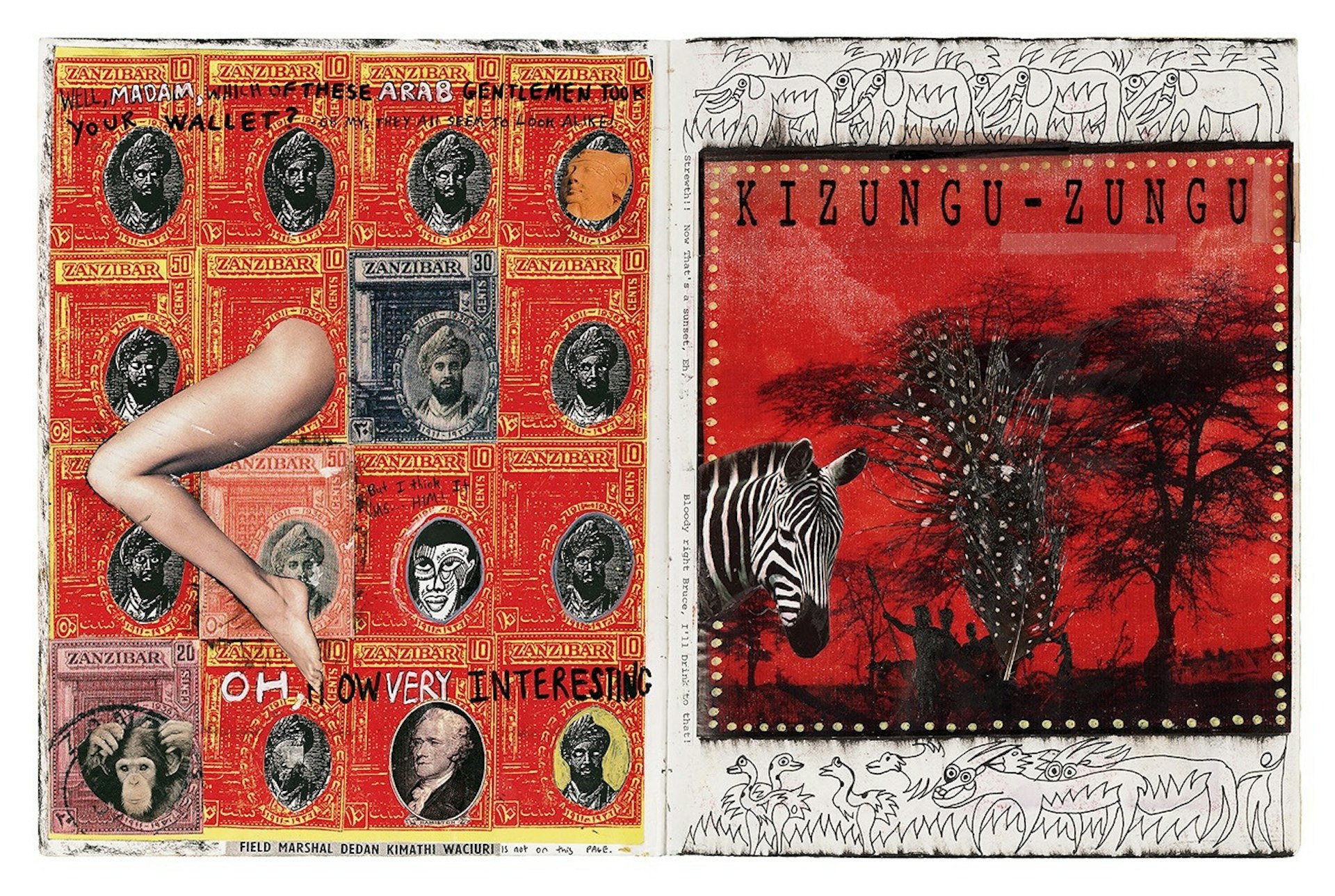

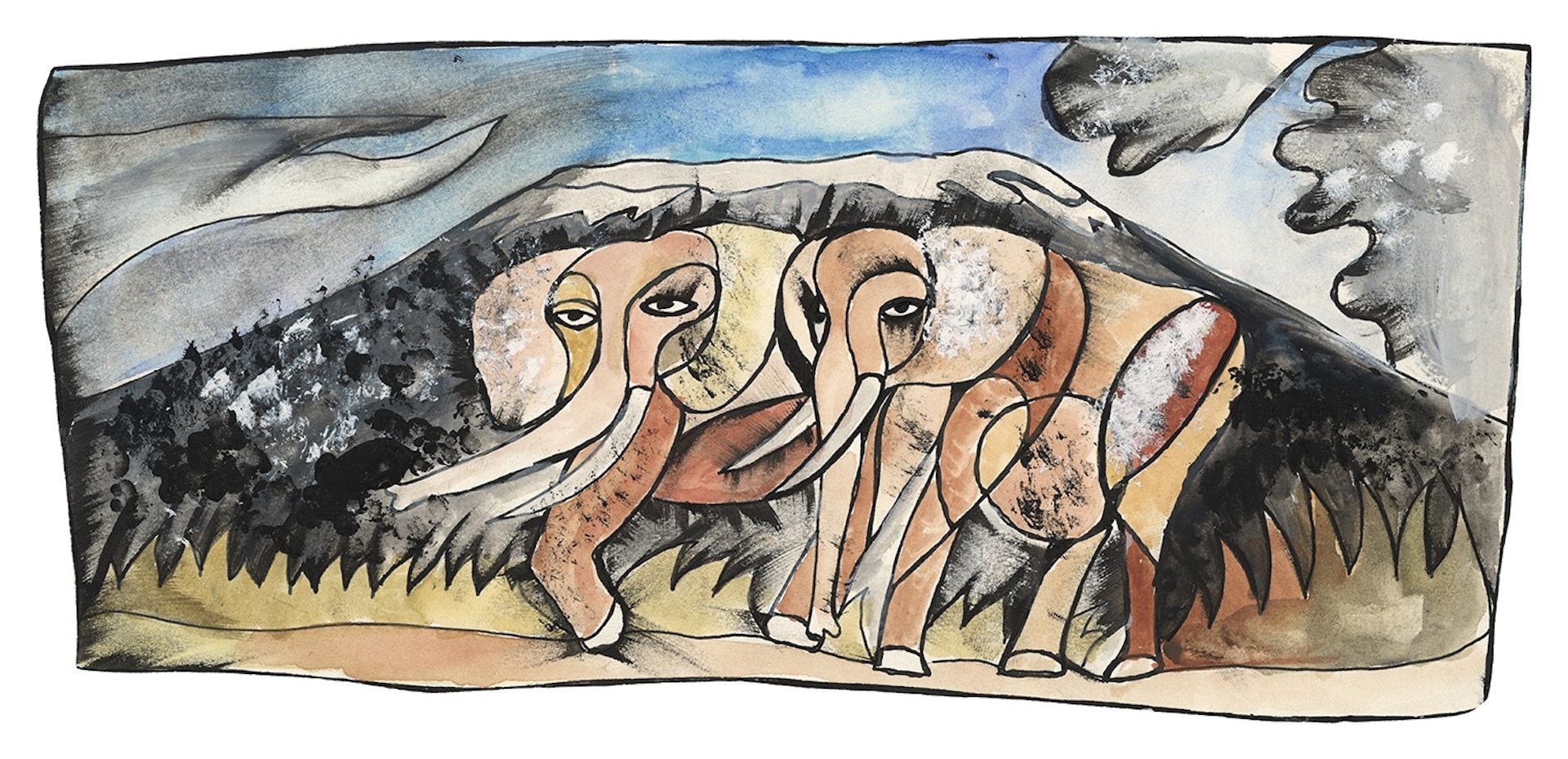

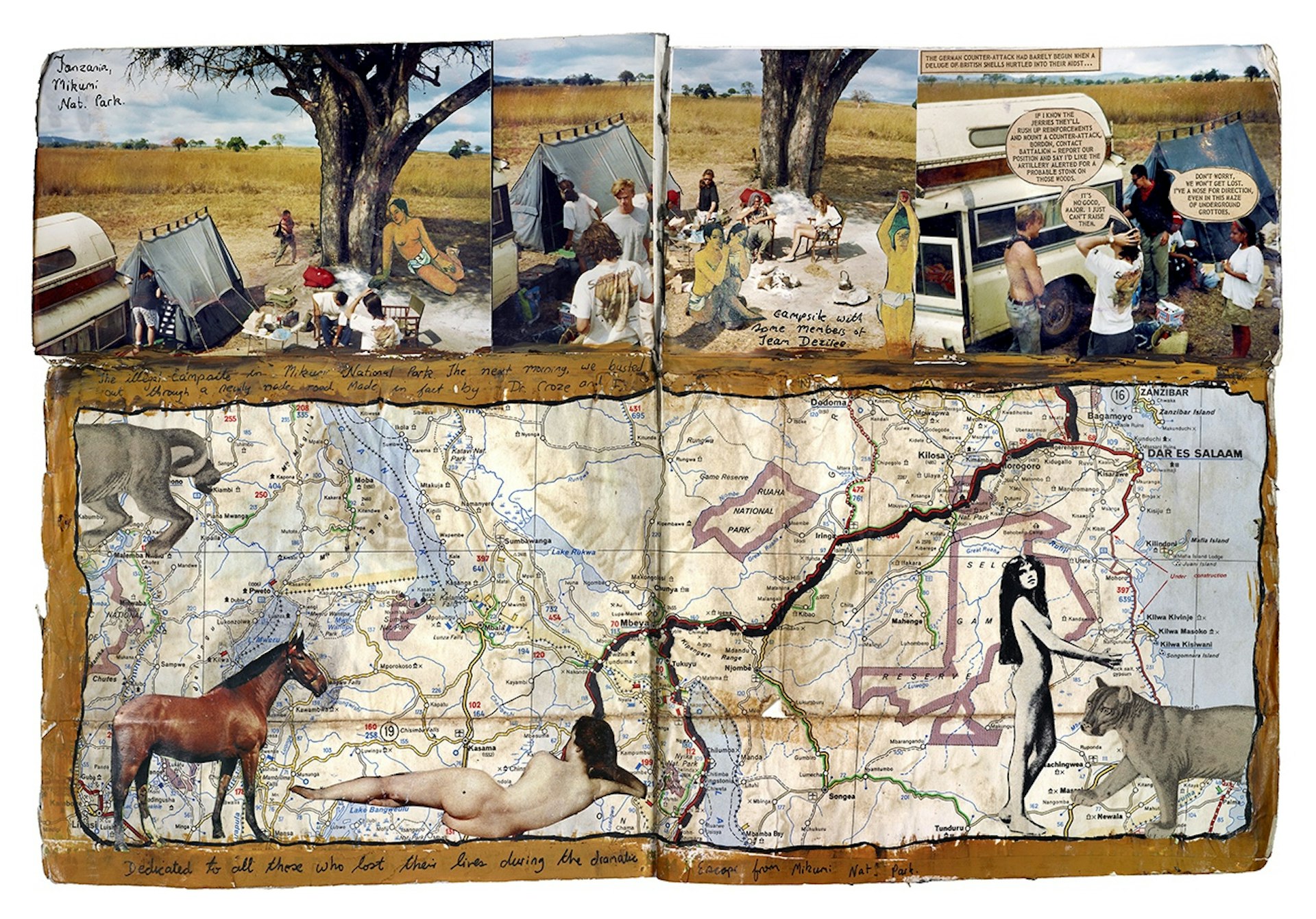

During a trip with his anthropology class to a Masaai village in Kenya’s Loita Hills, the teacher asked students to keep notebooks. Kathy remembers Dan’s as an “explosion of multimedia”, with dirt, blood and feathers arranged in visceral collages. It was his first journal and led to a lifelong passion, as Dan documented his life and journeys to more than 40 countries, in a series of bulging black-bound books.

In the autumn of 1988, Dan announced he was taking a year off before college. Though Kathy initially tried to talk him out of it, he explained that it would be an educational journey: “It’s a whole lot more challenging to live life firsthand,” he said, “to learn a language by actually being there, to learn about economics by bargaining in a souk in Casablanca.”

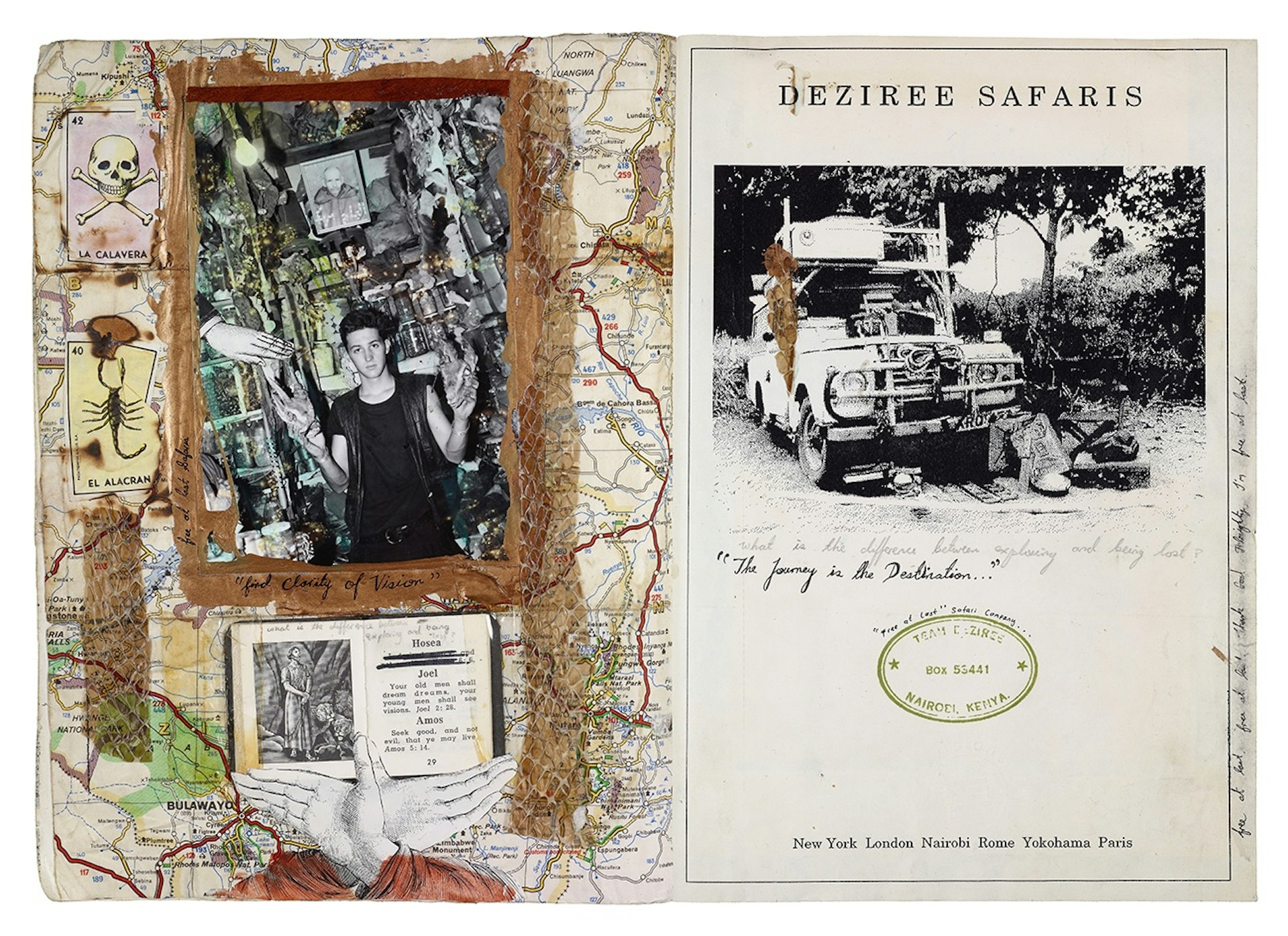

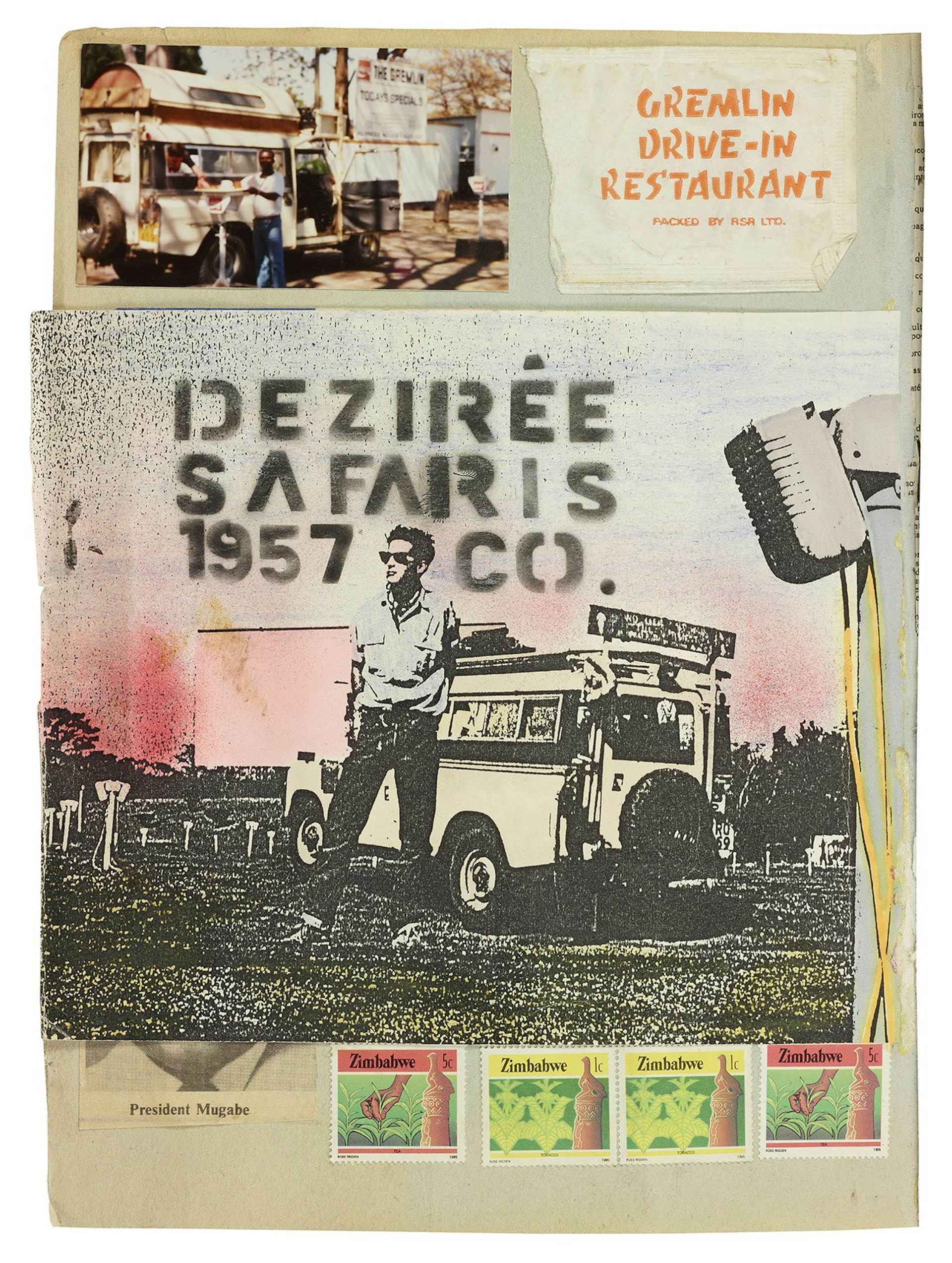

After a stint working as a graphic designer for Mademoiselle Magazine in New York, 18-year-old Dan returned to Nairobi with a grand idea. Purchasing an old Land Rover he named ‘Deziree’, he and a friend drove across five African countries. In Malawi, they encountered a vast refugee camp housing displaced Mozambicans fleeing civil war. The scene stuck with Dan and, while at Pasadena Community College in California, he founded a charity committed to helping the refugees.

After raising $17,000 for the venture, Dan and a group of 14 friends travelled thousands of miles to deliver the aid to the refugee camp, once smuggling the money across the border in a pillowcase. By the end of their trip, they had donated a land cruiser, blankets and money for two wells to aid organisations in the camp.

During Dan’s life, it seemed that each minute was precious, offering a window for whatever creative projects he put his mind to. He set up a business selling t-shirts, caps and postcards with images from his travels, radiating an infectious energy wherever he went.

In 1992, Dan heard about a possible famine in Somalia. Travelling with a friend from Reuters, he shot photos of dying Somalis that were picked up by global outlets – and helped ignite a humanitarian response, Operation Restore Hope. Moved by the power of his images to trigger action, Dan stayed on in Somalia, documenting the country’s spiral into a deadly civil war.

Despite the horrors he witnessed, his mother says that Dan could always see the best in people: “He had a gift for seeing their potential and helping them believe they could achieve it.”

Connection was a guiding philosophy throughout Dan’s life and something he always sought to achieve with people – regardless of who they were or where they were from. “Dan could connect at a human level,” continues Kathy. “He used humour a lot – often in a disarming way. Languages were also part of that connection; he could speak Swahili fluently and could get along in French, German and Arabic.”

In an interview with CNN in 1997, Kathy said that there was a visible change in Dan after bearing witness to the worsening humanitarian crisis in Somalia. “It affected him profoundly,” she explained. “[…] There was a depth to him and a pain that we had not seen before.”

On the day he was killed, Dan had his bags packed ready to leave Somalia. But while on the hotel rooftop with his colleagues, the sound of attack helicopters roared ominously overhead. Within minutes, the air exploded as they began bombing a nearby location – what we now know as the suspected house of warlord Aidid, except he wasn’t there. As dark smoke mushroomed from the scene, a group of Somalis arrived outside the hotel to ask if the journalists would go to the site of the attack to record the carnage. That July day, although packed and ready to depart, Dan chose to stay in Mogadishu.

![]()

Following Dan’s death, Kathy and Amy found solace in his journals.

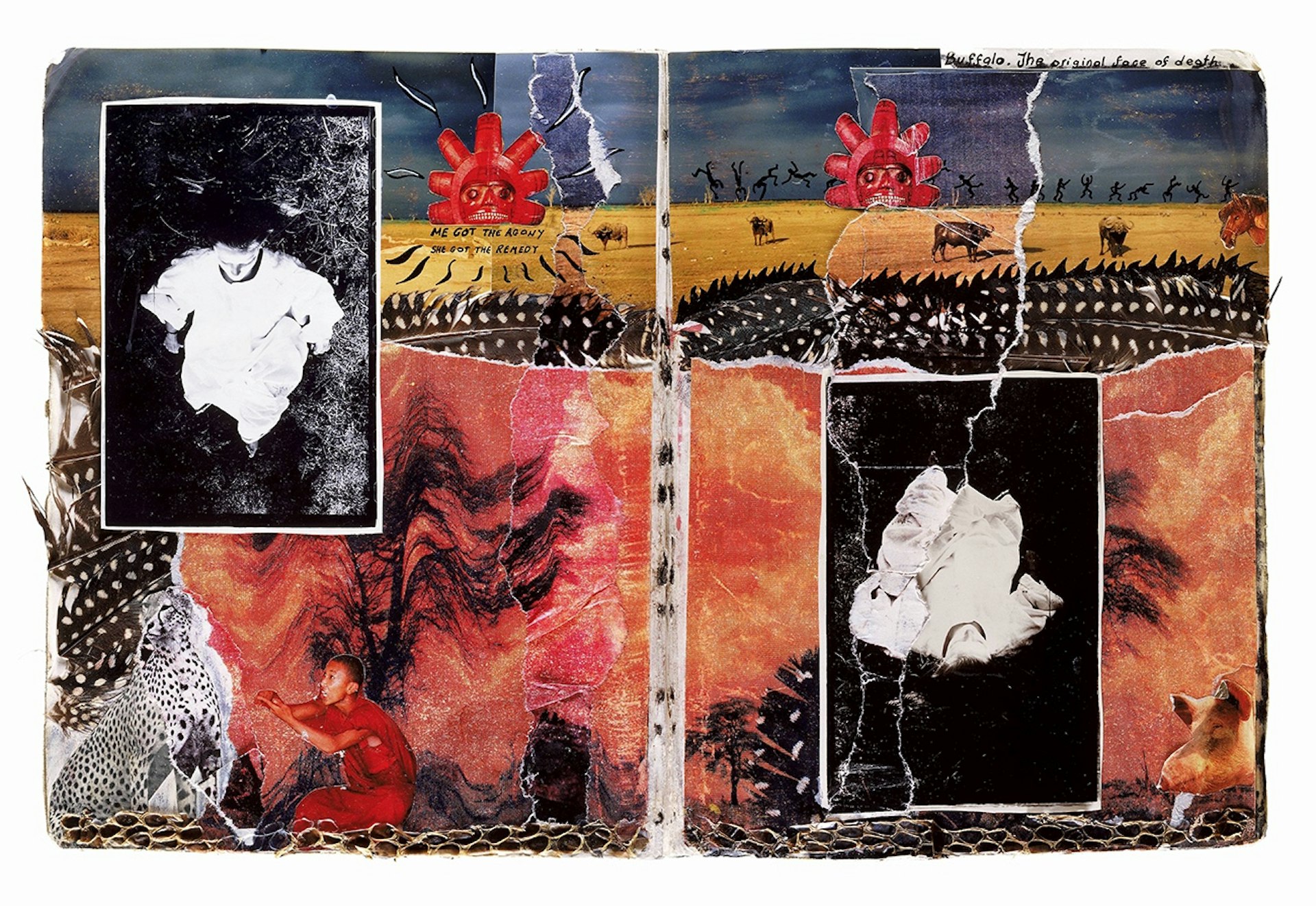

With some weighing up to five pounds, Kathy says they are like holding babies. Inside, pages are layered with ephemera from Dan’s expansive life: call cards from London telephone boxes, stamps, cut-outs from Russian newspapers, his drawings, random cartoons, maps – even a pressed scorpion. Anything that Dan could find would go in, the weirder the better.

“Dan covered some of his journal entries,” explains Kathy. “We know that he self-censored his work, so we don’t feel that publishing some of his pages is an invasion of his privacy. And of course, there are some things we haven’t shared publicly.”

Phantasmagoric and labyrinthine to navigate visually, it’s clear that the only true decipherer of the pages is Dan. In one of the journals, Kathy discovered a page titled ‘Mission Statement for Safari as a Way of Life.’ On it, Dan had written: “To explore the unknown and the familiar, distant and near, and to record in detail with the eyes of a child, any beauty, (of the flesh or otherwise), horror, irony, traces of utopia or hell.”

Distilled in a sentence was the essence of Dan’s vision. He resolved that each day would be an adventure, a safari. “When you are on safari, you’re open,” says Kathy. “Dan had an extraordinary way of making everything he did fun.”

Determined to channel their grief after Dan’s death into a positive force for good, Kathy and Amy founded Creative Visions in 1998, a foundation to support creative activists like Dan. As of today, their foundation has helped hundreds of artists, filmmakers, playwrights, and leaders of social movements on five continents to harness the power of media and the arts as vehicles of social change.

“Dan encouraged individuals to live more engaging lives, to explore both inner and outer worlds,” Kathy says. “He inspired people to believe there’s more to life.”

Learn more about Dan’s work and life on his official website.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.