The rebel photographer who shot life behind the Berlin Wall

- Text by Harald Hauswald

- Photography by Harald Hauswald/OSTKREUZ/Bundesstiftung Aufarbeitung

A version of this story appears in Huck 74: The Action Issue. Get your copy now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

I was already quite rebellious as a teenager. I hitchhiked a lot in the GDR [East Germany], following rock bands. But I found photography through my father. He was a freelance photographer who shot passport pictures, wedding photos. He forced me to do an apprenticeship.

I started in 1970 but stopped and became a rock technician, then did various other jobs. Then came my army national service. I moved to Berlin in 1978 and worked as a telegram messenger in Prenzlauer Berg. That’s when my photography really started. It felt like another way to rebel.

Deserters, May 1 Demonstration, Alexanderplatz, Mitte, Berlin, 1987

I wanted to be able to travel to the West so, for appearance’s sake, I got engaged to a West Berlin woman. In the meantime, I met a woman in East Berlin with whom I really fell in love. We had a child, and I took a picture of my daughter in a shopping basket in a mall, which became my first published picture. I gave it to my ‘ex’ in West Berlin in 1979 and she passed it to Der Tagesspiegel, the West German newspaper. I got paid 20 Deutsche Marks – she bought me a pair of jeans with the money.

From then, I regularly had photo essays published in West German periodicals. My film reels were smuggled out by western journalists and I had a secret bank account held by the mother of a West Berlin friend. People would bring me in cash or buy me cameras or equipment. In the first years I was published anonymously, but from 1986 I began to openly use my name. By then, the Stasi knew all about me.

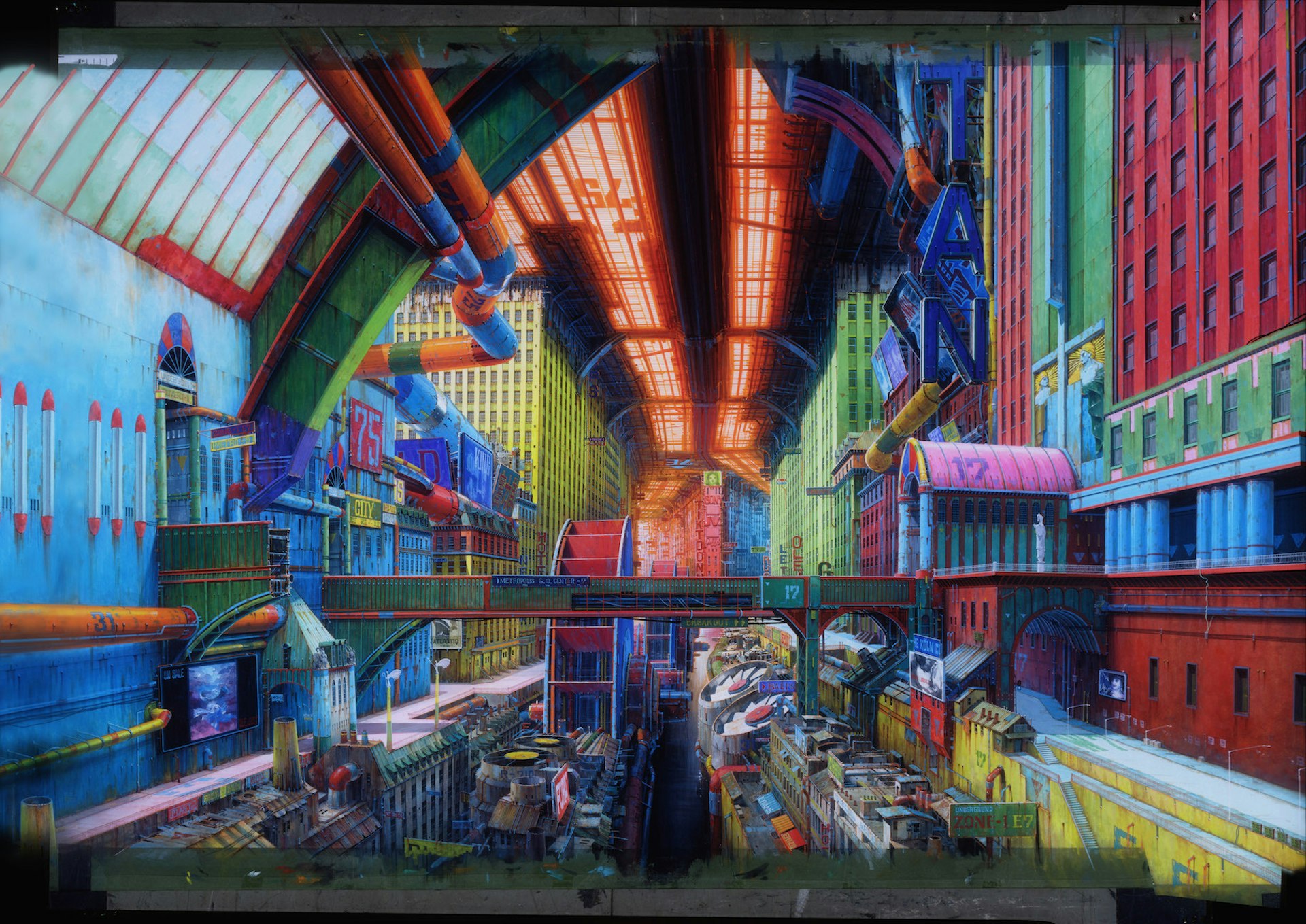

Subway Line A, Berlin, 1986

In 1987 my first book Ost-Berlin was published illegally in West Germany. Until then, photos directly from inside the GDR, together in a book, just didn’t happen. It became a political issue. I found out years later, through my Stasi file, that it reached Erich Mielke, head of the Stasi. If I could go back in time with that knowledge, I would take even more photos.

For me, photography was practical – not artistic. It was pure journalism. My ambition was always to document people. I am the only photographer in the GDR who shot both punks and hooligans. The first punks appeared in Berlin in the early 1980s and I admired them, because they openly showed their rebellion. They used to practice in churches, and I was able to take pictures, even though they hated photographers – sometimes they would beat them up.

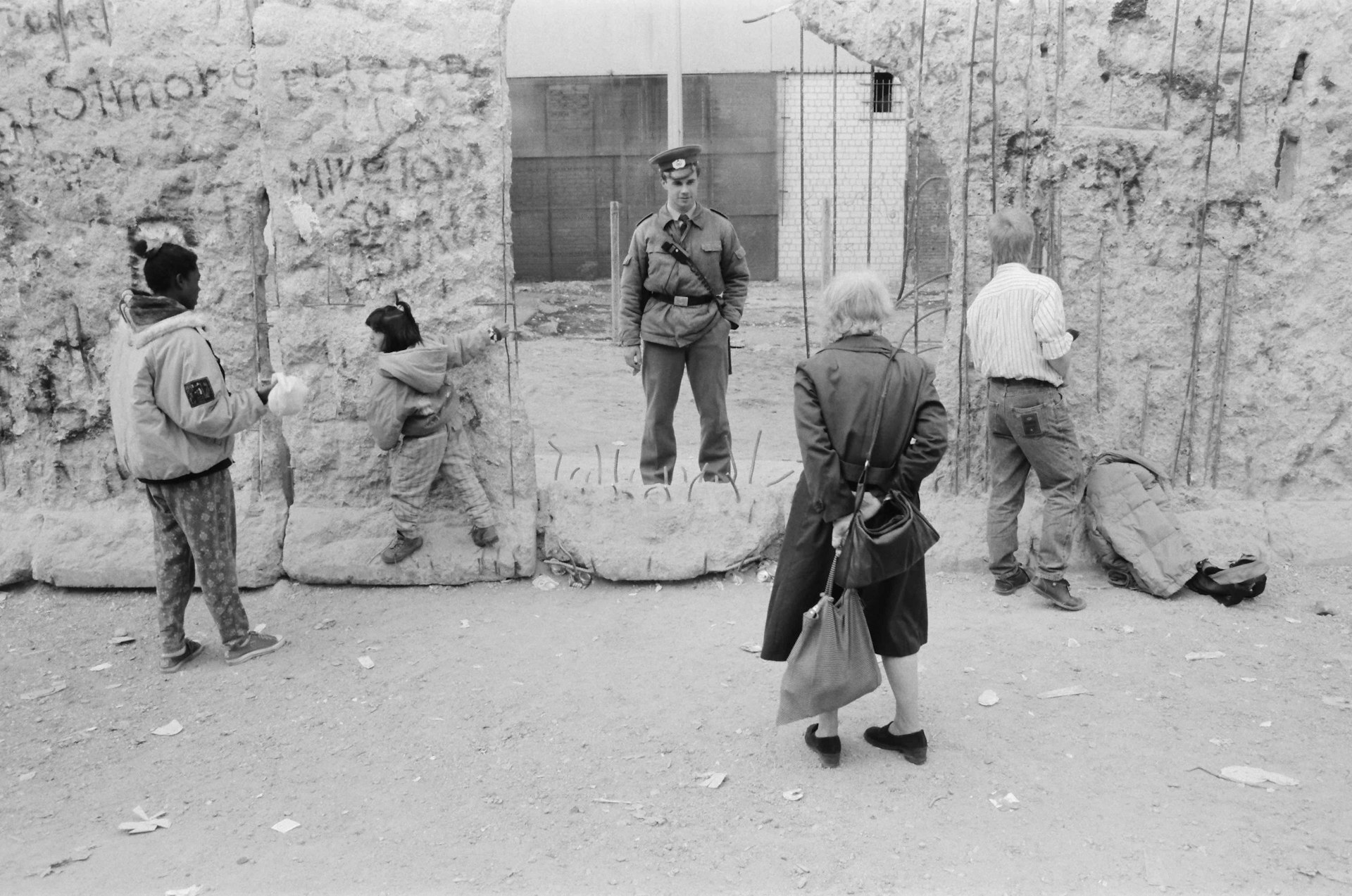

Berlin Wall, Mitte, Berlin, 1990

One of the best photographs I ever took was of people looking out towards the Berlin Wall, far off behind the Brandenburg Gate. It had symbolic meaning, not only for me, but for all GDR citizens. This was where the world ended: a view beyond the horizon, looking west. I also photographed the Berlin Wall several times, even though it was illegal. I would take pictures secretly, holding the camera at my hip.

My Stasi file is like a diary of my life spanning 12 years. If I ever write a memoir, I can use it to see where I was and when. The Stasi had more than 40 informants surveilling me under the codename ‘Radfahrer’ – ‘cyclist’. I was suspected of “treacherous passing of non-secret information”, “spying activities”, “anti-state agitation” and “money and currency offences”. At one point, a warrant was issued for my arrest – they could have put me in prison for a long time. They didn’t because I knew a lot of Western journalists: it would have meant a lot of international attention. But the Stasi still came for interrogations and house searches and shadowed me endlessly. Sometimes they took my daughter away.

In front of the Foreign Ministry of the GDR (now Schloßplatz), Mitte Berlin, 1984

For me, taking photographs that the GDR authorities did not like was a kind of inner liberation. To not be able to travel freely when you’re young is very depressing. Taking photographs was the work I did to fight against that feeling. A kind of tit for tat. If you hurt me, I hurt you.

I was at home in my darkroom in November 1989 when I heard that the Berlin Wall was opening. My girlfriend and I went straight to the Chauseestraße checkpoint. The first person I saw on the other side was a friend that had left 13 years ago. We hugged and cried like babies. We drove to a bar and soon all of Prenzlauer Berg was there and endless free beer flowed until 7am. It was the greatest liberation of my life. A feeling of pride only came later.

Deserters, May 1 Demonstration, Alexanderplatz, Mitte, Berlin, 1987

After the fall of the wall I went to Switzerland for an exhibition, I went to Paris, I was invited by Greenpeace to London. I had a lot of travelling to catch up on – my whole youth. I was 35 and it was like my second education had begun. It has yet to end.

Financially, I’ve struggled. At one point I was almost evicted. But now things are more stable. My new exhibition is the largest and most important of my life – an international stepping stone. It follows much work to conserve and digitise my catalogue, around 7,500 reels of film, revealing many photos which I’ve never seen before.

When I look back, it’s surprising. I realise how instinctively – without knowing the rest of the world during GDR times – I created work that deserves a place within the body of international photography. I’ve noticed, I’m actually not that bad.

(As told to Malcolm Jack)

Harald Hauswald: Voll das Leben! is on view at C/O Berlin, but currently temporarily closed due to COVID-19 measures.

Get your copy of Huck 74 now, or subscribe to make sure you never miss another issue.

Enjoyed this article? Like Huck on Facebook or follow us on Twitter.