Lukas Birk

- Text by Alex King

- Photography by Lukas Birk

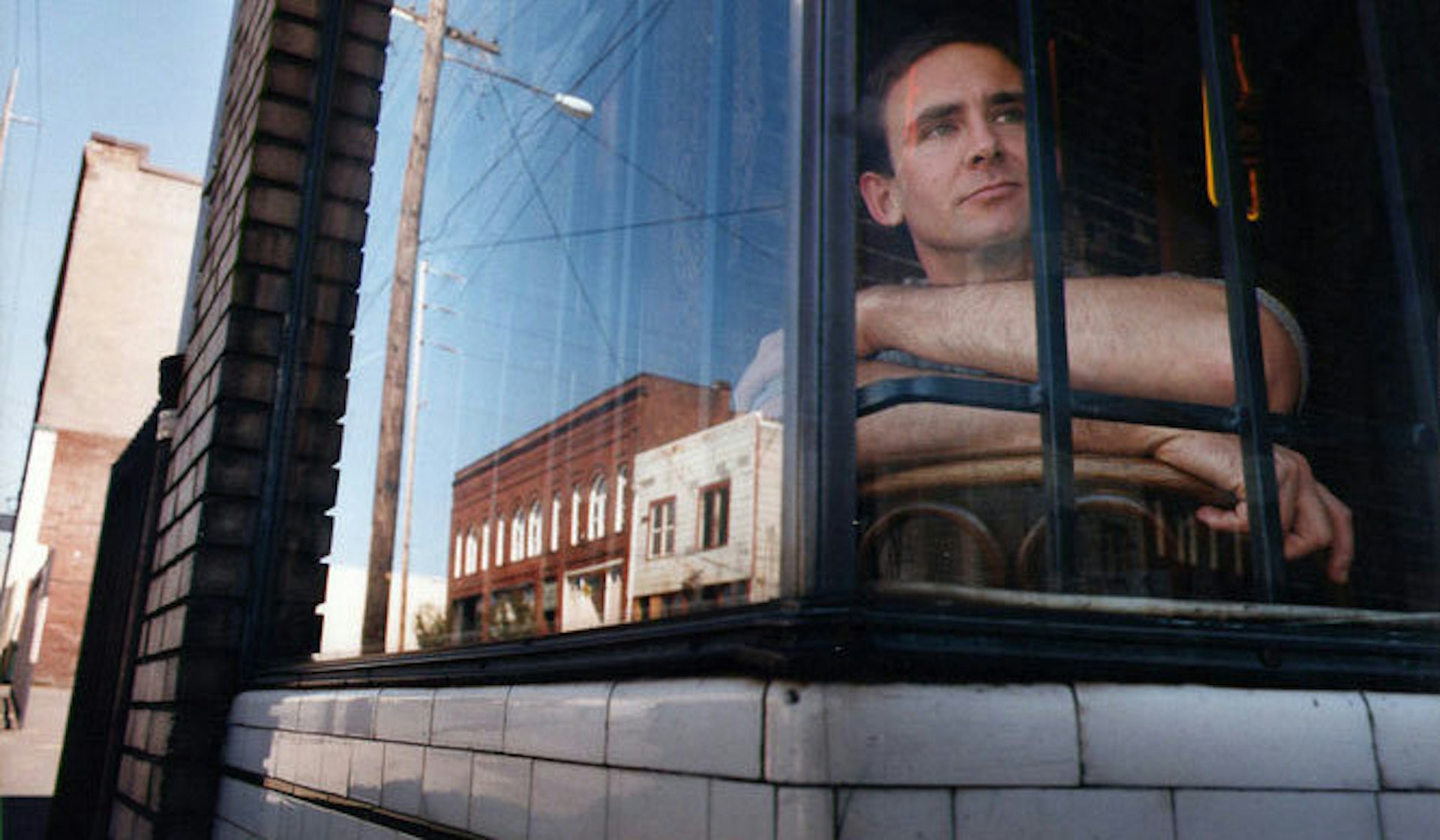

China’s fast pace of change both entranced and troubled Austrian artist Lukas Birk over the years he lived in Beijing. The constant destruction and construction meant it was impossible to know what would survive. Knowing the environment around him could soon be gone filled him with a what he describes as a sense of “pre-nostalgia.”

But it wasn’t until he stumbled across a box of his father’s expired Polaroid film that he realised he had found the perfect medium to convey his complex feelings about modern China. In his new book Polaroids from the Middle Kingdom: Old and New World Visions of China, Lukas uses the expired film to create images of the present that feel like they have emerged from a distant past.

When and why did you start shooting pictures?

I guess my first photo “shooting” was with a friend in his basement when we were about 13. We painted the walls in green and blue with a bright yellow arrow and tried to take portraits of us in different poses in front of it. I have no idea what kind of camera we had or what gave us the inspiration but the woman at the local lab said that the pictures were really good, so we felt like photographers.

I bought my first camera age 17 and was shooting a lot of black and white in the beginning as my father taught me how to operate in the darkroom. It was incredible exciting and I spent countless nights in my make-shift darkroom set up in the bathroom.

What is it you love about film photography?

Texture! The tactile sensations! Regardless of whether it’s Polaroid, Large Format or a simple 35mm roll. I still get excited by the material! The shutter sound of my analog EOS tells me “Now you took a photo!” It is substantial – it is definite. It’s not like “yeah maybe I just took a photograph!” You have to be in control with film and yet there is an uncontrollable element. It is hard for me to connect to the process of taking digital photographs. I can relate to the content of course, but it is also the process that inspires production.

What are you passionate about – interests, hobbies outside of photography – and how does this inform the images you take?

As with photography, I am passionate about manual things. Typewriters, stamps, the postal system, manual prints, train rides, odd souvenirs, things with a story. A lot of my work is a combination of images and objects I come across somewhere along the way. I travel a lot so naturally my work involves movement and incorporates this geographic diversity.

I collect a lot of photographic material too. In the last years I have been involved in research on photographic history in Afghanistan and Pakistan. Archiving has become a permanent word in my vocabulary. I have been given the nickname “librarian” and I guess in the future I will live up to it. I find a lot of pleasure in organising things too. I have set up an artist in residency program in Indonesia and co-founded another art program in China where we exhibit up 40 artists in an annual exhibition.

Who or what inspires your work? Any other photographers?

There are a number of people who I deeply respect for their determination. Their work might not have anything to do with my work but it is the narratives they are able to create and the world they form for you to delve in. Nobuyoshi Araki prolific approach and his constant movement is truly amazing. He creates a world for you and lives it himself.

Martin Parr is like a doctor with his uncomfortable intimate direct views. He is also a collector of all sorts of things. In the past, a lot of my inspiration came from travel writers who are able to create story lines that start on one continent and end up somewhere entirely different. Imagination works better without an image.

How did the Polaroids of the Middle Kingdom book come about? What’s the editing process like for you? Are you trying to tell stories with your images?

It was a natural process. I tried to find a way to tell the story of my China and especially my impressions of Beijing. Beijing was my home for several years and I had felt a certain nostalgia for the city and its fast pace of change. I started to become melancholic for things that were still there but I knew could be gone anytime. A pre-nostalgia.

By chance I found this wonderful expired Polaroid material leaving me with images of the present that felt like they had been taken a long time ago. I was able to produce images that gave exactly the kind of feeling I had felt in China. I found about 35 film packs and had around 200 working exposures in the end. Such a limited amount of material is fantastic. Firstly it keeps you very focused on what kind of moments and scenarios you want to capture and makes you think more about what is important to your story.

I had a lot of time for this series as it captured the places I went to over the cause of two and a half years. The camera was with me and when I had the feeling that this is right for my nostalgic story I took it out. The photos are pretty much documentary, except that I usually let people have a reaction to the camera and then press the shutter. There is an element of the self in the images and that is important as it is a personal and also emotional account. Each images tells its own story but I do think there is a clear narrative in the series.

If you had to take one photo that summed up your view on life, what would it capture?

It would need to be a photo that changes constantly. Maybe an instant photo with a developing time of 80 years. Slowly the grain and details reveal themselves. Who knows if the end result is as good as the middle of the process or the other way around.

Find out more about Lukas Birk’s Polaroids from the Middle Kingdom: Old and New World Visions of China, published by Glitterati Incorporated.